Lachlann Mac Ruaidhrí

Lachlann Mac Ruaidhrí (fl. 1297 – 1307/1308) was a Scottish magnate and chief of Clann Ruaidhrí.[note 1] He was a free-booting participant in the First War of Scottish Independence, who remarkably took up arms against figures such as John, King of Scotland; Edward I, King of England; the Guardians of Scotland; and his near-rival William II, Earl of Ross. Lachlann disappears from record in 1307/1308, and appears to have been succeeded by his brother, Ruaidhrí, as chief of Clann Ruaidhrí.

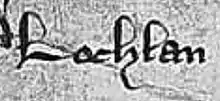

Lachlann Mac Ruaidhrí | |

|---|---|

Lachlann's name as it appears in correspondence between John Strathbogie, Earl of Atholl and Edward I, King of England[1] | |

| Predecessor | Ailéan mac Ruaidhrí |

| Successor | Ruaidhrí Mac Ruaidhrí |

| Noble family | Clann Ruaidhrí |

| Father | Ailéan mac Ruaidhrí |

Clann Ruaidhrí

.png.webp)

Lachlann was an illegitimate[12] son of Ailéan mac Ruaidhrí,[13] a son of Ruaidhrí mac Raghnaill, Lord of Kintyre,[13] eponym of Clann Ruaidhrí.[14] Ailéan had another illegitimate son,[15] Ruaidhrí,[13] and a legitimate daughter,[16] Cairistíona.[13] It was Lachlann's generation—the second generation in descent from Ruaidhrí mac Raghnaill—that members of Clann Ruaidhrí are first identified with a family name derived from this eponymous ancestor.[17][note 2] Clann Ruaidhrí was a branch of Clann Somhairle. Other branches of this overarching kindred included Clann Dubhghaill and Clann Domhnaill.[19] Lachlann was married to a daughter of Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill, Lord of Argyll.[20] Lachlann was therefore not only a brother-in-law of Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill's succeeding son, Eóin Mac Dubhghaill, but also the brother-in-law of a leading member of Clann Laghmainn, Maol Muire mac Laghmainn, and likely also brother-in-law of the chief of Clann Domhnaill, Alasdair Óg Mac Domhnaill, Lord of Islay.[21]

Career

In opposition to English adherents

.jpg.webp)

Ailéan disappears from record by 1296,[23] and seems to have died at some point before this date.[24] Although Cairistíona seems to have been Ailéan's heir, she was evidently supplanted by her brothers soon after his death.[25] Lachlann is first attested in contemporary sources in 1292.[26] In July of that year, he is mentioned in proceedings conducted at Berwick between Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill and Edward I, King of England, in which Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill personally promised to keep peace in the Hebrides, amicably settle his dispute with his Clann Domhnaill namesake and rival, Alasdair Óg, and bring the unruly Clann Ruaidhrí under the king's authority.[27] The fact that Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill vowed to have no dealings with his son Donnchadh and Lachlann—as these men were unwilling to submit to Edward I—suggests that Lachlann had earlier allied himself with Clann Dubhghaill in disputes with Clann Domhnaill.[26] The following year, in an effort to maintain peace in the western reaches of his realm, John, King of Scotland established the shrievalties of Skye and Lorn.[28] The former region—consisting of Wester Ross, Glenelg, Skye, Lewis and Harris, Uist, Barra, Eigg, Rhum, and the Small Isles—was given to William II, Earl of Ross, whilst the latter region—consisting of Argyll (except Cowal and Kintyre), Mull, Jura and Islay—was given to Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill.[29] Despite the king's intentions, his new sheriffs seem to have used their positions to exploit royal power against local rivals. Whilst Clann Domhnaill was forced to deal with its powerful Clann Dubhghaill rivals, Clann Ruaidhrí appears to have fallen afoul of the Earl of Ross over control of Kintail, Skye, and Uist.[30] Evidence of the earl's actions against Clann Ruaidhrí is revealed in correspondence between him and the English Crown in 1304. In this particular communiqué, William II recalled a costly military campaign which he had conducted in the 1290s against rebellious Hebridean chieftains—including Lachlann himself—at the behest of the then-reigning John (reigned 1292–1296).[31]

.png.webp)

In 1296, Edward I invaded and easily conquered the Scottish realm.[33] Amongst the Scots imprisoned by the English were many of the Ross elite, including William II himself. The earl remained in captivity from 1296 to 1303, a lengthy span of years in which the sons of Ailéan capitalised upon the resulting power vacuum.[34] Like most other Scottish landholders, Lachlann rendered homage to the triumphant king later in 1296.[35][note 3] One of the Scottish king's most ardent supporters had been Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill, a fact which appears to have led Edward I to use the former's chief rival, Alasdair Óg, the chief of Clann Domhnaill, as his primary agent in the maritime west. In this capacity, Alasdair Óg attempted to contain the Clann Dubhghaill revolt against English authority.[38]

The struggle between the two Clann Somhairle namesakes seems to be attested not long after Alasdair Óg's appointment in April 1296, and is documented in two undated letters from the latter to Edward I. In the first, Alasdair Óg complained to the king that Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill had ravaged his lands. Although Alasdair Óg further noted that he had overcome Ruaidhrí and thereby brought him to heel,[39] the fealty that Ruaidhrí swore to the English Crown appears to have been rendered merely as a stalling tactic,[40] since Lachlann then attacked Alasdair Óg, and both Clann Ruaidhrí brothers proceeded to ravage Skye and Lewis and Harris. At the end of the letter, the Clann Domhnaill chief implored upon Edward I to instruct the other noblemen of Argyll and Ross to aid him in his struggle against the king's enemies.[39][note 4]

In the second letter, Alasdair Óg again appealed to the English Crown, complaining that he faced a united front from Donnchadh, Lachlann, Ruaidhrí, and the Comyns. According to Alasdair Óg, the men of Lochaber had sworn allegiance to Lachlann and Donnchadh. In one instance Alasdair Óg reported that, although he had been able to force Lachlann's supposed submission, he was thereupon attacked by Ruaidhrí. The Clann Domhnaill chief further related a specific expedition in which he pursued his opponents to the Comyn stronghold of Inverlochy Castle[42]—the principal fortress in Lochaber[43]—where he was unable to capture—but nevertheless destroyed—two massive galleys which he described as the largest warships in the Western Isles. Much like in the first letter, Alasdair Óg called upon the English king for financial support in combating his mounting opponents.[42]

Alasdair Óg's dispatches seem to show that Lachlann and Ruaidhrí were focused upon seizing control of Skye and Lewis and Harris from the absentee Earl of Ross. Whilst the first communiqué reveals that the initial assault upon the islands concerned pillage, the second letter appears to indicate that the islands were subjected to further invasions by Clann Ruaidhrí, suggesting that the acquisition of these islands was the family's goal. The bitter strife between Clann Ruaidhrí and Clann Domhnaill depicted by these letters seems to indicate that both kindreds sought to capitalise on the earl's absence, and that both families sought to incorporate the islands into their own lordships. In specific regard to Clann Ruaidhrí, it is likely that the kindred's campaigning was an extension of the conflict originating from the creation of the shrievalty of Skye, granted to William II in 1293.[44] The correspondence also reveals that Lachlann and Ruaidhrí were able to split their forces and operate somewhat independently of each other. Although Alasdair Óg was evidently able to overcome one of them at a time, he was nevertheless vulnerable to a counterattack from the other.[45] Another aspect of the strife between the two kindreds is the possibility that it coincided with the anti-English campaign waged by Andrew Murray and Alexander Pilche against the embattled Countess of Ross in eastern Ross. If so, it is conceivable that there was some sort of communication and coordination between Clann Ruaidhrí and the Murray-Pilche coalition.[46] Lachlann's marital alliance with Clann Dubhghaill clearly benefited his kindred, linking it with the Comyn-Clann Dubhghaill pact in a coalition that encircled the Earldom of Ross.[47]

In opposition to Scottish patriots

Little else is known of Lachlann's activities until 1299. A report of an English spy at an important council of the Guardians of Scotland in August of this year reveals that news of devastations beyond the Firth of Forth committed by Lachlann and Alexander Comyn, younger brother of John Comyn, Earl of Buchan, was brought before leading Scottish magnates. According to the English informant, the severity of this news immediately quelled a heated quarrel that threatened the assembly itself.[53][note 6]

In June 1301, Edward I instructed the Admiral of the Cinque Ports, Gervase Alard, to take into the king's peace Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill, the latter's sons Eóin and Donnchadh, Lachlann himself, and Lachlann's wife and their followers.[56] Although no evidence of the admiral's activities off Scotland's western seaboard survive for that year, it is apparent that this impending submission of Clann Dubhghaill was regarded by the English as significant enough to divert the fleet. Clann Dubhghaill's conciliation with the English Crown may have been undertaken merely as a means to improve the family's own position, or possibly conducted on account of the apparent success of Clann Domhnaill's actions against them.[57]

In 1304, correspondence from John Strathbogie, Earl of Atholl to Edward I suggests that Lachlann was still working in concert with Alexander Comyn. John Strathbogie, evidently resentful of Alexander's appointment as Sheriff of Aberdeen, besought the English Crown not to allow him possession of Aboyne Castle as Alexander had not only two of the strongest castles in the north—Urquhart and Tarradale—but was working in league in Lachlann, who was then attempting boost his maritime forces by way of raising one galley of twenty oars per davoch of land. John Strathbogie's source of this information was William II and Thomas Dundee, Bishop of Ross.[59] Although the earl did not identify the said lands, they would appear to have been Clann Ruaidhrí territories such as Uist, Barra, the Small Isles and perhaps Skye.[60]

.png.webp)

In February 1306, Robert Bruce VII, Earl of Carrick, a claimant to the Scottish throne, killed his chief rival to the kingship, John Comyn III of Badenoch.[62] Although the former seized the throne (as Robert I) by March, the English Crown immediately struck back, defeating his forces in June. By September, Robert I was a fugitive, and appears to have escaped into the Hebrides.[63] According to the fourteenth-century Gesta Annalia II, Lachlann's sister, Cairistíona, played an instrumental part in Robert I's survival at this low point in his career, sheltering him along Scotland's western seaboard.[64][note 7] In any event, later the next year, at about the time of Edward I's death in July 1307, Robert I mounted a remarkable return to power by first consolidating control of Carrick.[70] In contrast to the evidence of assistance lent by Cairistíona to the Scottish king, Lachlann is recorded to have aligned himself closer with the English, as he appears to have personally sworn fealty to Edward I at Ebchester in August 1306, and petitioned for certain lands of Patrick Graham, a landholder forfeited from his estate for lending support to the Bruce cause. The document that preserves this petition records Lachlann's name as "Loughlā Mac Lochery des Isles".[71][note 8]

In October, there is evidence indicating that a certain Cristin del Ard delivered messages from the English Crown to William II, Lachlann, Ruaidhrí, and a certain Eóin Mac Neacail.[75] The latter appears to be the earliest member of Clann Mhic Neacail on record.[76] At about this time, this clan seems to have been seated on Skye and Lewis and Harris, and it is possible that the comital family of Ross had cultivated Clann Mhic Neacail as an ally against Clann Ruaidhrí shortly after the creation of the shrievalty of Skye in 1293.[77] Cristin was a close associate of William II, and the fact that the English Crown seems to have used the earl as a conduit for communications with Clann Ruaidhrí and Clann Mhic Neacail appears to indicate that the earl had brought the northwestern territories of these families back within his sphere of influence.[78] Whatever the case, William II played a key role in Robert I's misfortunes at about this time, as the earl captured the latter's wife and daughter—Elizabeth and Marjorie—and delivered them into the hands of Edward I.[79] The correspondence could have concerned this particular episode,[80] and may evince an attempt by the English Crown to project pro-English power into the Isles against Robert I and his supporters.[81]

In opposition to the Earl of Ross

.png.webp)

In 1303, after seven years of imprisonment, William II was released from captivity in England. It is possible that he had stubbornly refused to swear allegiance to the English until 1303, and that he only did so in a last attempt to safeguard what was left of his embattled earldom.[83] It appears that, upon regaining his domain, one of the responsibilies William II was tasked with was to bring the Hebrides under control.[84] However, he found himself facing a dangerous alliance between Alexander Comyn and the ever-strengthening Lachlann. This hostile front may account for the earl's part in John Strathbogie's correspondence to Edward I, as well as William II's 1304 communiqué to the king recounting his own part in combating Lachlann and other rebellious Hebrideans years before. Such correspondence suggest that the earl was attempting to instil doubts concerning the value of Lachlann and Alexander Comyn to English interests in the region, whilst highlighting his own usefulness.[85] Certainly by 1306, the English Crown granted Alexander Comyn's former stronghold of Urquhart to William II himself.[86]

Lachlann last appears on record in 1307/1308 in correspondence between William II and Edward II, King of England.[88] At the time, the earl appears to have found himself in a perilous position as the Earl of Buchan found himself the target of Robert I's attention late in 1307, and was soundly subdued by him in 1308.[89] This consolidation of power by the Scottish Crown was evidently not William II's only concern, as he reported to Edward II that Lachlann refused to render to him the revenues that Lachlann owed to the English Crown. In the words of William II, Lachlann "is such a high and mighty lord, he'll not answer to anyone except under great force or through fear of you".[88] The earl's letter is clearly a testimonial to the strength of Clann Ruaidhrí at this point in time,[90] evidently comparable to that of the earl.[91] In fact, it is possible that it was due to this kindred's considerable influence in the region that the Bruce cause found any support in Ross[92]—support evidenced by a letter to the English Crown in 1307 relating the unease of the English adherents Duncan Frendraught, Reginald Cheyne, and Gilbert Glencarnie.[93] Certainly, the fourteenth-century Chronicle of Lanercost reveals that Robert I received Hebridean support when he first launched his return from exile in Carrick/Galloway.[94] Having been in conflict with William II for over decade, it appears that Lachlann and his kin capitalised on Robert I's campaign against the earl and his confederates. The Scottish king's success against William II may well have stemmed from leading Islesmen like Lachlann himself.[95] In 1308, the earl submitted to Robert I,[96] and thereby offset aggression from his Clann Ruaidhrí adversaries.[97] Following Lachlann's last appearance on record, perhaps after his own demise,[98] Ruaidhrí seems to have succeeded him in representation of Clann Ruaidhrí.[99]

Succession

.jpg.webp)

Ruaidhrí appears to have only gained control of the lordship after swearing allegiance to Robert I.[101] Specifically, at some during the king's reign, Cairistíona resigned her claims with the condition that, if Ruaidhrí died without a male heir, and her like-named son married one of Ruaidhrí's daughters, Cairistíona's son would secure the inheritance.[102] Although there is uncertainty as to why the king allowed Ruaidhrí consolidate control of the kindred over his own close associate Cairistíona,[103] it is apparent that Ruaidhrí's faithful service to the king ensured the continuation of his kindred.[104]

At about the turn of the twentieth century, partisan historians of Clann Domhnaill portrayed Lachlann and his kin as "Highland rovers", and likened their exploits against Clann Domhnaill to the "piratical tendencies of the ancient Vikings".[105] Later in twentieth-century historical literature, Lachlann was still regarded a "sinister figure", likened to a "buccaneering predator", and described as a "shadowy figure ... always in the background, always a troublemaker".[106] Such summarisations of their lives are nevertheless oversimplifications of their recorded careers as vigorous regional lords.[107] According to the fifteenth-century manuscript National Library of Scotland Advocates' 72.1.1 (MS 1467), Lachlann had a son named Raghnall.[108]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Lachlann Mac Ruaidhrí | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Since the 1970s, academics have accorded Lachlann various patronyms in English secondary sources: Lachlan Mac Ruaidhri,[2] Lachlan Mac Ruairi,[3] Lachlan MacRuairi,[4] Lachlan MacRuairidh,[5] Lachlan MacRuari,[6] Lachlan macRuari,[7] Lachlan Macruarie,[8] Lachlan MacRuarie,[9] Lachlann Mac Ruaidhrí,[10] and Lochlan Macruari.[11]

- For example, in one particular piece of correspondence Lachlann is called "Laclan Magrogri".[18]

- In the record of his homage, Lachlann's name appears as "Rouland fiz Aleẏn Mac Rotherik".[35] Anglo-Norman clerics are otherwise known to have rendered forms of the Gaelic name Lachlann into forms of the more common Continental name Roland.[36] Lachlann is attested by numerous sources written in Latin and French, with about half of these according him forms of the name Roland.[37]

- According to early twentieth-century tradition in Ardnamurchan, two battles were fought in the bays between Gortenfern (grid reference NM 608 689) and Sgeir a' Chaolais (grid reference NM 623 702). Archaeological finds in the vicinity of Cul na Croise (grid reference NM 622 698)—a bay between Sgeir a Chaolais and Sgeir nam Meann—consist of spears, daggers, arrow-heads, and a coin dating to the reign of Edward I. These artefacts could indicate that Cul na Croise was the site of conflict fought in the context of the strife between Edward I's representative, Alasdair Óg, and the Clann Ruaidhrí brothers, Lachlann and Ruaidhrí. According to early twentieth-century local tradition, one of the battles fought in the area concerned a certain "Red Rover", and another fought nearby concerned an Irishman named "Duing" or "Dewing".[41]

- The escutcheon is blazoned: or, a galley sable with dragon heads at prow and stern and flag flying gules, charged on the hull with four portholes argent.[49] The coat of arms corresponds to the seal of Alasdair Mac Dubhghaill, Lachlann's father-in-law, distant kinsman, and ally.[50] Since the galley was a symbol of Clann Dubhghaill and seemingly Raghnall mac Somhairle—ancestor of Clann Ruaidhrí and Clann Domhnaill—it is conceivable that it was also a symbol of the Clann Somhairle progenitor, Somhairle mac Giolla Brighde.[51] It was also a symbol of the Crovan dynasty, which could mean that it passed to Somhairle's family through his wife.[52]

- Although it is likely that the Alexander Comyn recorded in the spy's report is indeed a younger brother of the Earl of Buchan, another possibility is that he was instead the brother of Lachlann's ally, John Comyn II of Badenoch.[54] In any case, Lachlann was certainly associated with the son of the earl in 1304.[55]

- Cairistíona was closely associated with Robert I. One possibility is that her husband, Donnchadh, was a younger son of Uilleam, Earl of Mar.[65] Another possibility is that Donnchadh was instead a son of Uilleam's son, Domhnall I, Earl of Mar.[66] Certainly, Domhnall I's daughter, Iseabail, was the first wife of Robert I,[67] and Domhnall I's son and comital successor, Gartnait, was the husband of a sister of Robert I.[68] Cairistíona's connections with the Mar kindred may well account for her support of the Bruce cause.[69]

- Patrick was a son-in-law of Lachlann's brother-in-law, Eóin Mac Dubhghaill.[72] The location of the lands petitioned by Lachlann is unknown. They may have been located in the Hebrides or west Highlands.[73]

Citations

- Bain (1884) p. 435 § 1633; Petitioners: John de Strathbogie, Earl of Atholl (n.d.).

- Duffy (1993).

- Holton (2017).

- Caldwell (2016); Brown (2011); Brown (2008); Caldwell (2004); McQueen (2002).

- Barrow, GWS (2006).

- Cochran-Yu (2015); Watson (2013); Fisher (2005); Sellar (2004a); Campbell of Airds (2000); Roberts (1999); Easson (1986).

- Roberts (1999).

- Barrow, GWS (2005); Barrow, GWS (1973).

- Watson (2013); Barrow, GWS (1992); Watson (1991); Barrow, GWS (1976).

- Murray, N (2002).

- Rixson (1982).

- Holton (2017) p. 153; Boardman, S (2006) p. 46; Ewan (2006); Barrow, GWS (2005) p. 377; McDonald (2004) p. 181; Barrow, GWS (1973) p. 381.

- Holton (2017) p. viii fig. 2; Fisher (2005) p. 86 fig. 5.2; Raven (2005b) fig. 13; Brown (2004) p. 77 tab. 4.1; Sellar (2000) p. 194 tab. ii; Roberts (1999) p. 99 fig. 5.2; McDonald (1997) p. 258 genealogical tree ii; Munro; Munro (1986) p. 279 tab. 1; Rixson (1982) p. 14 fig. 1.

- Holton (2017) pp. 126–127; Duffy (2007) p. 10; McDonald (2007) p. 110; McAndrew (2006) p. 66; Raven (2005a) p. 56; Raven (2005b) fig. 13; Murray, A (1998) p. 5.

- Holton (2017) p. 153; Boardman, S (2006) p. 46; Ewan (2006); McDonald (2004) p. 181; Barrow, GWS (1973) p. 381.

- Holton (2017) p. 153; Boardman, S (2006) p. 46; Ewan (2006); Barrow, GWS (2005) p. 219; McDonald (2004) p. 181; Roberts (1999) p. 143; Murray, A (1998) p. 5; McDonald (1997) pp. 174, 189; Munro; Munro (1986) p. 283 n. 13; Barrow, GWS (1973) p. 380.

- Bannerman (1998) p. 25; MacGregor (1989) pp. 24–25, 25 n. 51.

- Barrow, GWS (2005) p. 450 n. 104; MacGregor (1989) pp. 24–25, 25 n. 51; List of Diplomatic Documents (1963) p. 193; Bain (1884) p. 235 § 903; Stevenson (1870) pp. 189–191 § 445; Document 3/0/0 (n.d.c).

- Beuermann (2010) p. 108 n. 28.

- Holton (2017) p. 153; Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 58, 59 n. 38, 60; Boardman, S (2006) p. 54 n. 60; Sellar (2004a); Murray, N (2002) p. 222; Sellar (2000) p. 211; Duffy (1993) p. 158; Sellar (1971) p. 31; Calendar of the Patent Rolls (1895) p. 588; Bain (1884) p. 307 § 1204; Stevenson (1870) pp. 429–430 § 610; Document 1/27/0 (n.d.).

- Sellar (1971) p. 31.

- Statutes of England to 1320 (n.d.a).

- Holton (2017) p. 153; McDonald (1997) p. 189.

- Barrow, GWS (1973) p. 380.

- Holton (2017) pp. 153–154.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 55.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 55, 59–60; Brown (2011) p. 16; Barrow, GWS (2005) p. 76; Brown (2004) p. 258, 258 n. 4; McQueen (2002) p. 110; Sellar (2000) p. 212; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) pp. 204–205; Bain (1884) p. 145 § 621; Rymer; Sanderson (1816) p. 761; Document 3/33/0 (n.d.).

- Holton (2017) p. 151; Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 49–50; Watson (2013) ch. 1 ¶ 43; Brown (2011) p. 15; Young; Stead (2010b) p. 53; Stell (2005); Brown (2004) p. 258; Watson (1991) pp. 29 n. 27, 241; Reid, NH (1984) pp. 114, 148 n. 16, 413.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 49–50, 50 n. 3; Cameron (2014) p. 152; Petre (2014) pp. 270–272; Brown (2011) p. 15; Barrow, GWS (2006) p. 147; Brown (2004) p. 258; Barrow, GWS (1973) p. 383; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) pp. 216–217; The Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland (1844) p. 447; RPS, 1293/2/16 (n.d.a); RPS, 1293/2/16 (n.d.b); RPS, 1293/2/17 (n.d.a); RPS, 1293/2/17 (n.d.b).

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 50–51; Brown (2011) pp. 15–16; Boardman, S (2006) p. 19; Brown (2004) p. 258.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 50–51, 63–64; Brown (2011) p. 15; Brown (2008) pp. 31–32; Boardman, S (2006) p. 19; Brown (2004) p. 258; Watson (1991) p. 259; Bain (1884) pp. 434–435 § 1631, 435 § 1632; Document 3/20/5 (n.d); Document 3/20/6 (n.d).

- McAndrew (2006) p. 67; McDonald (1995) p. 132; Munro; Munro (1986) p. 281 n. 5; Rixson (1982) pp. 128, 219 n. 2; Macdonald (1904) p. 227 § 1793; MacDonald; MacDonald (1896) pp. 88–89; Laing (1866) p. 91 § 536.

- Prestwich (2008); Brown (2004) p. 259.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 51–57, 95–96.

- Holton (2017) pp. 156–157, 156 n. 126; Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 55; Barrow, GWS (1973) p. 381, 381 n. 2; Bain (1884) pp. 209–210 § 823; Instrumenta Publica (1834) p. 158; Document 6/2/0 (n.d.).

- Holton (2017) p. 157; Broun (2011) p. 275; Barrow, GWS (2006) p. 147 n. 28; Campbell of Airds (2000) p. 308 n. 42; Oram (2000) p. 215 n. 64; McDonald (1997) pp. 189, 190 n. 121; Duffy (1993) p. 75 n. 47; Rixson (1982) p. 208 n. 4; Barrow, GWS (1973) p. 381 n. 2.

- Holton (2017) p. 156 n. 126.

- Watson (2013) ch. 2 ¶ 18; McNamee (2012b) ch. 3; Young; Stead (2010a) pp. 68–69; Brown (2004) pp. 258–259; Rotuli Scotiæ (1814) p. 40; Document 5/1/0 (n.d.).

- Holton (2017) pp. 152–153; Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 56–57; Watson (2013) ch. 2 ¶ 49, 2 n. 52; Barrow, GWS (2006) p. 147; Barrow, GWS (2005) pp. 141, 450 n. 104; Brown (2004) pp. 259–260; Campbell of Airds (2000) p. 60; McDonald (1997) pp. 165, 190; Watson (1991) pp. 245–246; Rixson (1982) pp. 13–15, 208 n. 2, 208 n. 4; Barrow, GWS (1973) p. 381; List of Diplomatic Documents (1963) p. 193; Bain (1884) pp. 235–236 § 904; Stevenson (1870) pp. 187–188 § 444; Document 3/0/0 (n.d.b).

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 56.

- Lethbridge (1924–1925).

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 56–57, 60; Watson (2013) ch. 2 ¶¶ 49–50, 2 n. 52; Brown (2009) pp. 10–11; Barrow, GWS (2005) p. 141, 450 n. 104; Fisher (2005) p. 93; Brown (2004) p. 260; Campbell of Airds (2000) p. 60; Sellar (2000) p. 212; McDonald (1997) pp. 154, 165; Watson (1991) pp. 246–249; Munro; Munro (1986) p. 284 n. 18; Rixson (1982) pp. 15–16, 208 n. 4, 208 n. 6; Barrow, GWS (1973) p. 381; List of Diplomatic Documents (1963) p. 193; Bain (1884) p. 235 § 903; Stevenson (1870) pp. 189–191 § 445; Document 3/0/0 (n.d.c).

- Young; Stead (2010a) pp. 24, 102.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 57, 95–96.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 57–58.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 51–52, 58, 61, 95–96; Bain (1884) p. 239 § 922; Document 3/0/0 (n.d.a).

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 96.

- Woodcock; Flower; Chalmers et al. (2014) p. 419; Campbell of Airds (2014) p. 204; McAndrew (2006) p. 66; McAndrew (1999) p. 693 § 1328; McAndrew (1992); The Balliol Roll (n.d.).

- Woodcock; Flower; Chalmers et al. (2014) p. 419; McAndrew (2006) p. 66; The Balliol Roll (n.d.).

- McAndrew (2006) p. 66; McAndrew (1999) p. 693 § 1328; McAndrew (1992).

- Campbell of Airds (2014) pp. 202–203.

- Johns (2003) p. 139.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 58–59, 59 n. 37; Penman (2014) pp. 60, 62–63; Watson (2013) ch. 3 ¶ 68; Barrow, GWS (2006) p. 147; Barrow, GWS (2005) pp. 140–141, 450 n. 99, 450 n. 103; Watson (2004a); McQueen (2002) p. 199; Watson (1991) pp. 101, 252–253, 252 n. 43; Reid, NH (1984) pp. 174–175; Barrow, GWS (1973) p. 381; Bain (1884) pp. 525–526 § 1978.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 59 n. 37; Watson (1991) p. 252 n. 43.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 59 n. 37.

- Holton (2017) p. 153; Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 59; Watson (2013) ch. 4 ¶¶ 78–80; Campbell of Airds (2000) p. 60; Sellar (2000) p. 211; McDonald (1997) p. 168; Watson (1991) pp. 255, 271; Reid, WS (1960) pp. 10–11; Calendar of the Patent Rolls (1895) p. 588; Bain (1884) p. 307 § 1204; Stevenson (1870) pp. 429–430 § 610; Document 1/27/0 (n.d.).

- Watson (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 80.

- Woodcock; Flower; Chalmers et al. (2014) p. 110; McAndrew (2006) p. 44; McAndrew (1999) pp. 674, 703; The Balliol Roll (n.d.).

- Caldwell (2016) pp. 363–364; Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 62–65, 63 n. 50; Brown (2008) pp. 31–32; Barrow, GWS (2006) p. 147; Barrow, GWS (2005) p. 202; Caldwell (2004) pp. 74–75; Watson (2004b); Watson (1991) p. 254; Oram (1988) p. 344; Easson (1986) pp. 85–86, 125, 159–160; Macphail (1916) p. 237; Bain (1884) p. 435 § 1633.

- Caldwell (2016) p. 364; Barrow, GWS (2006) p. 147; Easson (1986) p. 85 n. 191.

- Birch (1905) p. 135 pl. 20.

- Barrow, GWS (2008); Young (2004); McDonald (1997) p. 169.

- Barrow, GWS (2008); McDonald (1997) pp. 170–174.

- Caldwell (2016) p. 360; Penman (2014) pp. 104, 359 n. 82; Caldwell (2012) p. 284; Young; Stead (2010a) p. 92; Scott (2009) ch. 8 ¶ 46; Brown (2008) p. 19; Duncan (2007) pp. 19, 118 n. 725–62; Boardman, S (2006) pp. 49 n. 6, 55 n. 61; McDonald (2006) p. 79; Barrow, GWS (2005) p. 219; Brown (2004) p. 262; Duffy (2002) p. 60; Traquair (1998) p. 140; McDonald (1997) pp. 174, 189, 196; Goldstein (1991) p. 279 n. 32; Munro; Munro (1986) p. 283 n. 13; Reid, NH (1984) pp. 293–294; Barrow, GWS (1973) pp. 380–381; Barnes; Barrow (1970) p. 47; Mackenzie (1909) p. 407 n. 133; Eyre-Todd (1907) p. 77 n. 1; Skene (1872) p. 335 ch. 121; Skene (1871) p. 343 ch. 121.

- Jack (2016) pp. 84, 84 n. 219, 253; Pollock (2015) p. 179 n. 122; Brown (2011) p. 15; Oram (2003) p. 64, 64 n. 84.

- Jack (2016) p. 84 n. 219; Beam (2012) p. 58, 58 n. 23; Caldwell (2012) p. 284; McNamee (2012b) ch. 5 ¶ 51; Findlater (2011) p. 69; Young; Stead (2010a) p. 92; Scott (2009) ch. 8 ¶¶ 43–44; Boardman, S (2006) p. 46; McDonald (2006) p. 79; Barrow, GWS (2005) pp. 219, 246 tab. ii; McDonald (2004) p. 188; Oram (2003) p. 64 n. 84; Roberts (1999) p. 132; McDonald (1997) pp. 189, 258 genealogical tree ii n. 1; Duncan (1996) pp. 582–583; Goldstein (1991) p. 279 n. 32; Munro; Munro (1986) p. 283 n. 13; Barrow, GWS (1973) p. 380.

- Jack (2016) pp. 262–263 tab. 1, 264 tab. 2; Penman (2014) p. 39; Beam (2012) p. 58, 58 n. 23; Caldwell (2012) p. 284; McNamee (2012b) ch. 5 ¶ 51; Brown (2011) p. 13, 13 n. 55; Findlater (2011) p. 69; Barrow, LG (2010) p. 4; Young; Stead (2010a) pp. 22 tab., 92; Scott (2009) ch. 8 ¶ 44; Barrow, GWS (2008); Boardman, S (2006) p. 46; Barrow, GWS (2005) pp. 184, 219, 245–246 tab. ii; McDonald (2004) p. 188; Cannon; Hargreaves (2001) p. 142; Roberts (1999) p. 132; McDonald (1997) p. 189; Goldstein (1991) p. 279 n. 32.

- Jack (2016) pp. 262–263 tab. 1, 264 tab. 2; Penman (2014) pp. 27, 39; Daniels (2013) p. 95; McNamee (2012b) ch. 5 ¶ 51; Brown (2011) p. 13; Young; Stead (2010a) p. 22 tab.; Duncan (2008); Boardman, S (2006) p. 46; Barrow, GWS (2005) pp. 58, 184, 219, 245–246 tab. ii; Watson (2004a); Watson (2004b); Ross (2003) p. 171; Cannon; Hargreaves (2001) p. 142.

- Watson (2013) ch. 1 ¶ 32; McDonald (2006) p. 79; Barrow, GWS (2005) pp. 219–220; McDonald (1997) p. 174.

- Barrow, GWS (2008); Barrow, GWS (2005) pp. 220–224; McDonald (1997) pp. 174–175; Skene (1872) p. 335 ch. 121; Skene (1871) p. 343 ch. 121.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 70–71, 71 n. 87; Barrow, GWS (2006) p. 147; Barrow, GWS (2005) p. 423; Barrow, GWS (1992) pp. 168–169; Barrow, GWS (1976) pp. 163–164; Barrow, GWS (1973) pp. 381–382; Palgrave (1837) p. 310 § 142.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 58; Penman (2014) p. 223; Barrow, GWS (2005) p. 488 n. 103; Sellar (2004b); Penman (1999) p. 49.

- Barrow, GWS (1992) pp. 168–169.

- Chesshyre; Woodcock; Grant et al. (1992) p. 277; McAndrew (2006) p. 136; The Balliol Roll (n.d.).

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 72; Brown (2008) p. 20; Sellar; Maclean (1999) pp. 6–7; Document 5/3/0 (n.d.b); Simpson; Galbraith (n.d.) p. 205 § 472w.

- Sellar; Maclean (1999) pp. 6–8.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 51.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 72–73.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 73; Barrow, GWS (2005) pp. 207–208; Barrow, GWS (2004); Sellar; Maclean (1999) pp. 6–7.

- Sellar; Maclean (1999) pp. 6–7.

- Brown (2008) p. 20.

- McAndrew (2006) pp. 43 n. 19, 44; Macdonald (1904) p. 66 § 587; Fraser (1888) pp. 454 § 4, 464 fig. 14; Laing (1850) p. 42 § 223.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 61; Brown (2004) p. 194.

- Watson (2013) ch. 7 ¶ 7.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 62–64, 74.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 67–68, 74; Document 5/3/0 (n.d.c); Simpson; Galbraith (n.d.) p. 216 § 492xvi.

- Statutes of England to 1320 (n.d.b).

- Holton (2017) p. 154; Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 73; Barrow, GWS (2005) pp. 228–229; McDonald (1997) p. 190; Reid, NH (1984) pp. 300–301; Rixson (1982) pp. 18–19, 208 n. 10; Barrow, GWS (1973) p. 382; Bain (1888) pp. 382 § 1837, 400 § 14; Document 3/20/7 A (n.d.).

- McNamee (2012a) ch. 2; Neville (2012) p. 1; Barrow, GWS (2005) pp. 226–228; Watson (2004a); McQueen (2002) p. 223.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 75; Rixson (1982) pp. 18–19.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 75.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 75, 75 n. 109; McNamee (2012a) ch. 2; Brown (2008) pp. 31–32.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 75, 75 n. 109; Bain (1884) p. 513 § 1926; Document 5/3/0 (n.d.a).

- McNamee (2012a) ch. 2 n. 28; Maxwell (1913) p. 188; Stevenson (1839) p. 212.

- Brown (2008) pp. 31–32; Brown (2004) p. 262.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 75–76; Penman (2014) pp. 108–109; Young; Stead (2010a) p. 114; Reid, NH (1984) p. 306.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 76.

- McDonald (1997) pp. 190–191.

- Barrow, GWS (2005) p. 377; McDonald (1997) pp. 190–191.

- Adv MS 72.1.1 (n.d.); Black; Black (n.d.).

- Barrow, GWS (2005) p. 377.

- Boardman, S (2006) pp. 46, 55 n. 61; Ewan (2006); Barrow, GWS (2005) pp. 377–378; Raven (2005a) p. 63; Boardman, SI (2004); Brown, M (2004) p. 263; Duffy (1993) p. 207 n. 75; Munro; Munro (1986) p. 283 nn. 13–14; Macphail (1916) p. 235; Thomson (1912) pp. 428–429 § 9; MacDonald; MacDonald (1896) pp. 495–496.

- Boardman, S (2006) p. 46; Brown (2004) p. 263.

- Boardman, S (2006) p. 46.

- Holton (2017) pp. 147–148; McDonald (1997) p. 190; MacDonald; MacDonald (1896) p. 87.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 55, 95–96; McDonald (2006) p. 79; Barrow, GWS (2005) p. 377; McDonald (1997) p. 190.

- Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 55, 95–96.

- Munro; Munro (1986) p. 284 n. 18; Adv MS 72.1.1 (n.d.); Black; Black (n.d.).

- Petre (2014) p. 268 tab.; Brown (2004) p. 77 fig. 4.1; Sellar (2000) p. 194 tab. ii.

References

Primary sources

- "National Library of Scotland Adv MS 72.1.1". Irish Script on Screen. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. n.d. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- Bain, J, ed. (1884). Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House.

- Bain, J, ed. (1888). Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland. Vol. 4. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House.

- Society Of Antiquaries Of London (1992). "Heraldic Device". In Chesshyre, DHB; Woodcock, T; Grant, GJ; Hunt, WG; Sykes, AG; Graham, IDG; Moffett, JC (eds.). Dictionary of British Arms: Medieval Ordinary. Vol. 1. London: Society of Antiquaries of London. doi:10.5284/1049652. ISBN 0-85431-258-7.

- Black, R; Black, M (n.d.). "Kindred 32 MacRuairi". 1467 Manuscript. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- Calendar of the Patent Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office: Edward I, A.D. 1292–1301. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1895.

- "Document 1/27/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- "Document 3/0/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d.a. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- "Document 3/0/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d.b. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- "Document 3/0/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d.c. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- "Document 3/20/5". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- "Document 3/20/6". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- "Document 3/20/7 A". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- "Document 3/33/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- "Document 5/1/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- "Document 5/3/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d.a. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- "Document 5/3/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d.b. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- "Document 5/3/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- "Document 6/2/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- Instrumenta Publica Sive Processus Super Fidelitatibus Et Homagiis Scotorum Domino Regi Angliæ Factis, A.D. MCCXCI–MCCXCVI. Edinburgh: The Bannatyne Club. 1834. OL 14014961M.

- List of Diplomatic Documents, Scottish Documents, and Papal Bulls Preserved in the Public Record Office. Lists and Indexes. New York: Kraus Reprint Corporation. 1963 [1923].

- MacDonald, A (1896). The Clan Donald. Vol. 1. Inverness: The Northern Counties Publishing Company.

- Maxwell, H, ed. (1913). The Chronicle of Lanercost, 1272–1346. Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons.

- Palgrave, F, ed. (1837). Documents and Records Illustrating the History of Scotland and the Transactions Between the Crowns of Scotland and England. Vol. 1. The Commissioners on the Public Records of the Kingdom.

- "Petitioners: John de Strathbogie, Earl of Atholl. Name(s): John Addressees: ..." The National Archives. n.d. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- Rotuli Scotiæ in Turri Londinensi. Vol. 1. His Majesty King George III. 1814.

- "RPS, 1293/2/16". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. n.d.a. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- "RPS, 1293/2/16". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. n.d.b. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- "RPS, 1293/2/17". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. n.d.a. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- "RPS, 1293/2/17". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. n.d.b. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- Rymer, T; Sanderson, R, eds. (1816). Fœdera, Conventiones, Litteræ, Et Cujuscunque Generis Acta Publica, Inter Reges Angliæ, Et Alios Quosvis Imperatores, Reges, Pontifices, Principes, Vel Communitates. Vol. 1, pt. 2. London. hdl:2027/umn.31951002098036i.

- Simpson, GG; Galbraith, JD, eds. (n.d.). Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland. Vol. 5. Scottish Record Office.

- Skene, WF, ed. (1871). Johannis de Fordun Chronica Gentis Scotorum. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. OL 24871486M.

- Skene, WF, ed. (1872). John of Fordun's Chronicle of the Scottish Nation. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. OL 24871442M.

- "Statutes of England to 1320". Digital Bodleian. n.d.a. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "Statutes of England to 1320". Digital Bodleian. n.d.b. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1839). Chronicon de Lanercost, M.CC.I.–M.CCC.XLVI. Edinburgh: The Bannatyne Club. OL 7196137M.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1870). Documents Illustrative of the History of Scotland. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House.

- The Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland. Vol. 1. 1844. hdl:2027/mdp.39015035897480.

- "The Balliol Roll". The Heraldry Society of Scotland. n.d. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- Thomson, JM, ed. (1912). Registrum Magni Sigilli Regum Scotorum: The Register of the Great Seal of Scotland, A.D. 1306–1424 (New ed.). Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House. hdl:2027/njp.32101038096846.

- Society Of Antiquaries Of London (2014). "Heraldic Device". In Woodcock, T; Flower, S; Chalmers, T; Grant, J (eds.). Dictionary of British Arms: Medieval Ordinary. Vol. 4. London: Society of Antiquaries of London. doi:10.5284/1049652. ISBN 978-0-85431-297-9.

Secondary sources

- Bannerman, J (1998) [1993]. "MacDuff of Fife". In Grant, A; Stringer, KJ (eds.). Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 20–38. ISBN 0-7486-1110-X.

- Barnes, PM; Barrow, GWS (1970). "The Movements of Robert Bruce between September 1307 and May 1308". Scottish Historical Review. 49 (1): 46–59. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25528838.

- Barrow, GWS (1973). The Kingdom of the Scots: Government, Church and Society From the Eleventh to the Fourteenth Century. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Barrow, GWS (1976). "Lothian in the First War of Independence, 1296–1328". Scottish Historical Review. 55 (2): 151–171. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25529181.

- Barrow, GWS (1992). Scotland and its Neighbours in the Middle Ages. London: The Hambledon Press. ISBN 1-85285-052-3.

- Barrow, GWS (2004). "Elizabeth (d. 1327)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54180. Retrieved 12 December 2015. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Barrow, GWS (2005) [1965]. Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-2022-2.

- Barrow, GWS (2006). "Skye From Somerled to A.D. 1500" (PDF). In Kruse, A; Ross, A (eds.). Barra and Skye: Two Hebridean Perspectives. Edinburgh: The Scottish Society for Northern Studies. pp. 140–154. ISBN 0-9535226-3-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- Barrow, GWS (2008). "Robert I (1274–1329)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (October 2008 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3754. Retrieved 20 January 2014. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Barrow, LG (2010). "Fourteenth-Century Scottish Royal Women, 1306–1371: Pawns, Players and Prisoners". Journal of the Sydney Society for Scottish History. 13: 2–20.

- Beam, A (2012). "'At the Apex of Chivalry': Sir Ingram de Umfraville and the Anglo-Scottish Wars, 1296–1321". In King, A; Simpkin, D (eds.). England and Scotland at War, c.1296–c.1513. History of Warfare. Edinburgh: Brill. pp. 53–76. ISBN 978-90-04-22983-9. ISSN 1385-7827.

- Beuermann, I (2010). "'Norgesveldet?' South of Cape Wrath? Political Views Facts, and Questions". In Imsen, S (ed.). The Norwegian Domination and the Norse World c. 1100–c. 1400. Trondheim Studies in History. Trondheim: Tapir Academic Press. pp. 99–123. ISBN 978-82-519-2563-1.

- Birch, WDG (1905). History of Scottish Seals. Vol. 1. Stirling: Eneas Mackay. OL 20423867M.

- Boardman, S (2006). The Campbells, 1250–1513. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-0-85976-631-9.

- Boardman, SI (2004). "MacRuairi, Ranald, of Garmoran (d. 1346)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54286. Retrieved 5 July 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Broun, D (2011). "The Presence of Witnesses and the Writing of Charters" (PDF). In Broun, D (ed.). The Reality Behind Charter Diplomatic in Anglo-Norman Britain. Glasgow: Centre for Scottish and Celtic Studies, University of Glasgow. pp. 235–290. ISBN 978-0-85261-919-3.

- Brown, M (2004). The Wars of Scotland, 1214–1371. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0748612386.

- Brown, M (2008). Bannockburn: The Scottish War and the British Isles, 1307–1323. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3332-6.

- Brown, M (2009). Scottish Baronial Castles, 1250–1450. Botley: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-872-3.

- Brown, M (2011). "Aristocratic Politics and the Crisis of Scottish Kingship, 1286–96". Scottish Historical Review. 90 (1): 1–26. doi:10.3366/shr.2011.0002. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241.

- Caldwell, DH (2004). "The Scandinavian Heritage of the Lordship of the Isles". In Adams, J; Holman, K (eds.). Scandinavia and Europe, 800–1350: Contact, Conflict, and Coexistence. Medieval Texts and Cultures of Northern Europe. Vol. 4. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. pp. 69–83. doi:10.1484/M.TCNE-EB.3.4100. ISBN 2-503-51085-X.

- Caldwell, DH (2012). "Scottish Spearmen, 1298–1314: An Answer to Cavalry". War in History. 19 (3): 267–289. doi:10.1177/0968344512439966. eISSN 1477-0385. ISSN 0968-3445. S2CID 159886666.

- Caldwell, DH (2016). "The Sea Power of the Western Isles of Scotland in the Late Medieval Period". In Barrett, JH; Gibbon, SJ (eds.). Maritime Societies of the Viking and Medieval World. The Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph. Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 350–368. doi:10.4324/9781315630755. ISBN 978-1-315-63075-5. ISSN 0583-9106.

- Cameron, C (2014). "'Contumaciously Absent'? The Lords of the Isles and the Scottish Crown". In Oram, RD (ed.). The Lordship of the Isles. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 146–175. doi:10.1163/9789004280359_008. ISBN 978-90-04-28035-9. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Campbell of Airds, A (2000). A History of Clan Campbell. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: Polygon at Edinburgh. ISBN 1-902930-17-7.

- Campbell of Airds, A (2014). "West Highland Heraldry and The Lordship of the Isles". In Oram, RD (ed.). The Lordship of the Isles. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 200–210. doi:10.1163/9789004280359_010. ISBN 978-90-04-28035-9. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Cannon, J; Hargreaves, A (2001). The Kings & Queens of Britain. Oxford Paperback Reference. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280095-7.

- Cochran-Yu, DK (2015). A Keystone of Contention: The Earldom of Ross, 1215–1517 (PhD thesis). University of Glasgow.

- Daniels, PW (2013). The Second Scottish War of Independence, 1332–41: A National War? (MA thesis). University of Glasgow.

- Duffy, S (1993). Ireland and the Irish Sea Region, 1014–1318 (PhD thesis). Trinity College, Dublin. hdl:2262/77137.

- Duffy, S (2002). "The Bruce Brothers and the Irish Sea World, 1306–29". In Duffy, S (ed.). Robert the Bruce's Irish Wars: The Invasions of Ireland 1306–1329. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. pp. 45–70. ISBN 0-7524-1974-9.

- Duffy, S (2007). "The Prehistory of the Galloglass". In Duffy, S (ed.). The World of the Galloglass: Kings, Warlords and Warriors in Ireland and Scotland, 1200–1600. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-1-85182-946-0.

- Duncan, AAM (1996) [1975]. Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom. The Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Mercat Press. ISBN 0-901824-83-6.

- Duncan, AAM, ed. (2007) [1997]. The Bruce. Canongate Classics. Edinburgh: Canongate Books. ISBN 978-0-86241-681-2.

- Duncan, AAM (2008). "Brus, Robert (VI) de, Earl of Carrick and Lord of Annandale (1243–1304)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (October 2008 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3753. Retrieved 19 January 2014. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Duncan, AAM; Brown, AL (1956–1957). "Argyll and the Isles in the Earlier Middle Ages" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 90: 192–220. doi:10.9750/PSAS.090.192.220. eISSN 2056-743X. ISSN 0081-1564. S2CID 189977430.

- Easson, AR (1986). Systems of Land Assessment in Scotland Before 1400 (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/6869.

- Ewan, E (2006). "MacRuairi, Christiana, of the Isles (of Mar)". In Ewan, E; Innes, S; Reynolds, S; Pipes, R (eds.). The Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women: From the Earliest Times to 2004. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 244. ISBN 0-7486-1713-2. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- Eyre-Todd, G, ed. (1907). The Bruce: Being the Metrical History of Robert Bruce King of the Scots. London: Gowans & Gray. OL 6527461M.

- Findlater, AM (2011). "Sir Enguerrand de Umfraville: His Life, Descent and Issue" (PDF). Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society. 85: 67–84. ISSN 0141-1292.

- Fisher, I (2005). "The Heirs of Somerled". In Oram, RD; Stell, GP (eds.). Lordship and Architecture in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland. Edinburgh: John Donald. pp. 85–95. ISBN 978-0-85976-628-9. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- Fraser, W, ed. (1888). The Red Book of Menteith. Vol. 2. Edinburgh. OL 25295262M.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Goldstein, RJ (1991). "The Women of the Wars of Independence in Literature and History". Studies in Scottish Literature. 26 (1): 271–282. ISSN 0039-3770.

- Holton, CT (2017). Masculine Identity in Medieval Scotland: Gender, Ethnicity, and Regionality (PhD thesis). University of Guelph. hdl:10214/10473.

- Jack, KS (2016). Decline and Fall: The Earls and Earldom of Mar, c.1281–1513 (PhD thesis). University of Stirling. hdl:1893/25815.

- Johns, S (2003). Noblewomen, Aristocracy and Power in the Twelfth-Century Anglo-Norman Realm. Gender In History. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-6304-3.

- Laing, H (1850). Descriptive Catalogue of Impressions From Ancient Scottish Seals, Royal, Baronial, Ecclesiastical, and Municipal, Embracing a Period From A.D. 1094 to the Commonwealth. Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club. OL 24829707M.

- Laing, H (1866). Supplemental Descriptive Catalogue of Ancient Scottish Seals, Royal, Baronial, Ecclesiastical, and Municipal, Embracing the Period From A.D. 1150 to the Eighteenth Century. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. OL 24829694M.

- Lethbridge, TC (1924–1925). "Battle Site in Gorten Bay, Kentra, Ardnamurchan" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 59: 105–113. doi:10.9750/PSAS.059.105.108. eISSN 2056-743X. ISSN 0081-1564. S2CID 251800892.

- Macdonald, WR (1904). Scottish Armorial Seals. Edinburgh: William Green and Sons. OL 23704765M.

- MacGregor, MDW (1989). A Political History of the MacGregors Before 1571 (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/6887.

- Mackenzie, WM, ed. (1909). The Bruce. London: Adam and Charles Black.

- Macphail, JRN, ed. (1916). Highland Papers. Publications of the Scottish History Society. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: T. and A. Constable. OL 24828785M.

- McAndrew, BA (1992). "Some Ancient Scottish Arms". The Heraldry Society. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- McAndrew, BA (1999). "The Sigillography of the Ragman Roll" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 129: 663–752. doi:10.9750/PSAS.129.663.752. eISSN 2056-743X. ISSN 0081-1564. S2CID 202524449.

- McAndrew, BA (2006). Scotland's Historic Heraldry. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843832614.

- McDonald, RA (1995). "Images of Hebridean Lordship in the Late Twelfth and Early Thirteenth Centuries: The Seal of Raonall Mac Sorley". Scottish Historical Review. 74 (2): 129–143. doi:10.3366/shr.1995.74.2.129. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25530679.

- McDonald, RA (1997). The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard, c. 1100–c. 1336. Scottish Historical Monographs. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. ISBN 978-1-898410-85-0.

- McDonald, RA (2004). "Coming in From the Margins: The Descendants of Somerled and Cultural Accommodation in the Hebrides, 1164–1317". In Smith, B (ed.). Britain and Ireland, 900–1300: Insular Responses to Medieval European Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 179–198. ISBN 0-511-03855-0.

- McDonald, RA (2006). "The Western Gàidhealtachd in the Middle Ages". In Harris, B; MacDonald, AR (eds.). Scotland: The Making and Unmaking of the Nation, c.1100–1707. Vol. 1. Dundee: Dundee University Press. ISBN 978-1-84586-004-2.

- McDonald, RA (2007). Manx Kingship in its Irish Sea Setting, 1187–1229: King Rǫgnvaldr and the Crovan Dynasty. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-84682-047-2.

- McNamee, C (2012a) [1997]. The Wars of the Bruces: Scotland, England and Ireland, 1306–1328. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-0-85790-495-9.

- McNamee, C (2012b) [2006]. Robert Bruce: Our Most Valiant Prince, King and Lord. Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited. ISBN 978-0-85790-496-6.

- McQueen, AAB (2002). The Origins and Development of the Scottish Parliament, 1249–1329 (PhD thesis). University of St Andrews. hdl:10023/6461.

- Munro, J; Munro, RW (1986). The Acts of the Lords of the Isles, 1336–1493. Scottish History Society. Edinburgh: Scottish History Society. ISBN 0-906245-07-9.

- Murray, A (1998). Castle Tioram: The Historical Background. Glasgow: Cruithne Press.

- Murray, N (2002). "A House Divided Against Itself: A Brief Synopsis of the History of Clann Alexandair and the Early Career of "Good John of Islay" c. 1290–1370". In McGuire, NR; Ó Baoill, C (eds.). Rannsachadh na Gàidhlig 2000: Papers Read at the Conference Scottish Gaelic Studies 2000 Held at the University of Aberdeen 2–4 August 2000. Aberdeen: An Clò Gaidhealach. pp. 221–230. ISBN 0952391171.

- Neville, CJ (2012). "Royal Mercy in Later Medieval Scotland". Florilegium. 29: 1–31. doi:10.3138/flor.29.1.

- Oram, RD (1988). The Lordship of Galloway, c. 1000 to c. 1250 (PhD thesis). University of St Andrews. hdl:10023/2638.

- Oram, RD (2000). The Lordship of Galloway. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 0-85976-541-5.

- Oram, RD (2003). "The Earls and Earldom of Mar, c.1150–1300". In Boardman, S; Ross, A (eds.). The Exercise of Power in Medieval Scotland, 1200–1500. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 46–66.

- Penman, M (1999). "A Fell Coniuracioun Agayn Robert the Douchty King: The Soules Conspiracy of 1318–1320". The Innes Review. 50 (1): 25–57. doi:10.3366/inr.1999.50.1.25. eISSN 1745-5219. hdl:1893/2106. ISSN 0020-157X.

- Penman, M (2014). Robert the Bruce: King of the Scots. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14872-5.

- Petre, JS (2014). "Mingary in Ardnamurchan: A Review of who Could Have Built the Castle" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 144: 265–276. doi:10.9750/PSAS.144.265.276. eISSN 2056-743X. ISSN 0081-1564. S2CID 258758433.

- Pollock, MA (2015). Scotland, England and France After the Loss of Normandy, 1204–1296: 'Auld Amitie'. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-992-7.

- Prestwich, M (2008). "Edward I (1239–1307)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (January 2008 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8517. Retrieved 15 September 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Raven, JA (2005a). Medieval Landscapes and Lordship in South Uist (PhD thesis). Vol. 1. University of Glasgow.

- Raven, JA (2005b). Medieval Landscapes and Lordship in South Uist (PhD thesis). Vol. 2. University of Glasgow.

- Reid, NH (1984). The Political Rôle of the Monarchy in Scotland, 1249–1329 (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/7144.

- Reid, WS (1960). "Sea-Power in the Anglo-Scottish War, 1296–1328". The Mariner's Mirror. 46 (1): 7–23. doi:10.1080/00253359.1960.10658467. ISSN 0025-3359.

- Rixson, D (1982). The West Highland Galley. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 1-874744-86-6.

- Roberts, JL (1999). Lost Kingdoms: Celtic Scotland and the Middle Ages. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-0910-5.

- Ross, A (2003). "The Lords and Lordship of Glencarnie". In Boardman, S; Ross, A (eds.). The Exercise of Power in Medieval Scotland, 1200–1500. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 159–174.

- Scott, RN (2009) [1982]. Robert the Bruce, King of Scots (EPUB). Edinburgh: Canongate Books. ISBN 978-1-84767-746-4.

- Sellar, WDH (1971). "Family Origins in Cowal and Knapdale". Scottish Studies: The Journal of the School of Scottish Studies, University of Edinburgh. 15: 21–37. ISSN 0036-9411.

- Sellar, WDH (2000). "Hebridean Sea Kings: The Successors of Somerled, 1164–1316". In Cowan, EJ; McDonald, RA (eds.). Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. pp. 187–218. ISBN 1-86232-151-5.

- Sellar, WDH (2004a). "MacDougall, Alexander, Lord of Argyll (d. 1310)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49385. Retrieved 5 July 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Sellar, WDH (2004b). "MacDougall, John, Lord of Argyll (d. 1316)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54284. Retrieved 5 July 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Sellar, WDH; Maclean, A (1999). The Highland Clan MacNeacail (MacNicol): A History of the Nicolsons of Scorrybreac. Lochbay: Maclean Press. ISBN 1-899272-02-X.

- Stell, GP (2005). "John [John de Balliol] (c.1248x50–1314)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (October 2005 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1209. Retrieved 6 September 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Traquair, P (1998). Freedom's Sword. Niwot: Roberts Rinehart. ISBN 1-57098-247-3. OL 8730008M.

- Watson, F (2004a). "Comyn, John, Seventh Earl of Buchan (c.1250–1308)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6047. Retrieved 25 September 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Watson, F (2004b). "Strathbogie, John of, Ninth Earl of Atholl (c.1260–1306)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49383. Retrieved 24 December 2015. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Watson, F (2013) [1998]. Under the Hammer: Edward I and Scotland, 1286–1306 (EPUB). Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-1-907909-19-1.

- Watson, F (1991). Edward I in Scotland: 1296–1305 (PhD thesis). University of Glasgow.

- Watson, F (2004a). "Bruce, Christian (d. 1356)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/60019. Retrieved 9 April 2016. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Watson, F (2004b). "Donald, Eighth Earl of Mar (1293–1332)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/18021. Retrieved 12 December 2015. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Young, A (2004). "Comyn, Sir John, Lord of Badenoch (d. 1306)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6046. Retrieved 25 September 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Young, A; Stead, MJ (2010a) [1999]. In the Footsteps of Robert Bruce in Scotland, Northern England and Ireland. Brimscombe Port: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5642-3.

- Young, A; Stead, MJ (2010b) [2002]. In the Footsteps of William Wallace, In Scotland and Northern England. Brimscombe Port: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5638-6.

External links

- "Roland (Lachlan), son of Alan MacRuairi". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371.

Media related to Lachlann Mac Ruaidhrí at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lachlann Mac Ruaidhrí at Wikimedia Commons

.jpg.webp)