Lake Flannigan

Lake Flannigan is a natural freshwater lake on King Island, Tasmania, Australia, situated four kilometres (two point five miles) south of the Cape Wickham Lighthouse, in the northern locality of Wickham.[1]

| Lake Flannigan | |

|---|---|

| Big Lake (1886–1911) | |

Lake Flannigan Location in Tasmania | |

| Location | King Island, Tasmania |

| Coordinates | 39°37′05″S 143°57′25″E |

| Etymology | Michael John Flannigan |

| Basin countries | Australia |

| Max. length | 2 km (1.2 mi) |

| Max. width | 1.5 km (0.93 mi) |

| Surface area | 150 ha (370 acres) |

At approximately 150 hectares (370 acres), it is the largest body of water on King Island. The size of the lake fluctuates significantly. In times of sustained high rainfall the length can reach almost 2 kilometres (1.2 mi), and its width in some parts can be up to 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi).[2]

The floor of the lake lies 15.25 metres (50.0 ft) AHD .[3]: 62 Reports of the depth of the water vary widely from 9.1 metres (30 ft) in 1887[4] to 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) in 2007 after a period of severe drought coupled with the previous mis-direction of drainage into the lake.[5]

The lake is visible from Springs Road to the south, and Cape Wickham Road to the east.

Classification

The lake is surrounded by private farmland but is itself Crown land; part of its south eastern shore is classified as "Public Reserve".

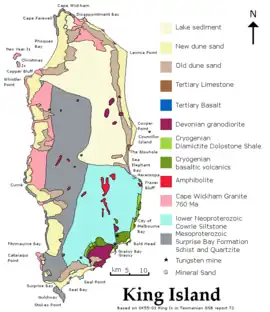

Jennings explains that geologically the lake is classed as "a complex dune barrage lake" (Jennings, 1957, p. 62). The water in the lake drains underground to The Springs, 1.3 kilometres (0.8 miles) to the west on the coast. Water levels in the lake are affected by its complex geology, including calcareous and quartz sands, granite hills and dune formations. Natural processes, such as waves on the lake and storm winds contribute to erosion, which in turn impacts water levels.[3]: 63

Since Michael John Flannigan wrote his first survey report about the island in 1896,[6] the lake has been acknowledged as being in need of some degree of government protection. Flannigan foresaw that "if the frontages of these lakes [Bob and Egg Lagoons and Big Lake] are blocked by settlers it will be detrimental to the balance of the country" (Flannigan, 1896, page 4).

The lake shores were first gazetted as a reserve in 1913, when the Tasmanian Government Gazette[7] officially announced the creation of a sanctuary for wild fowl fringing the lake. But in July 1921 the King Island News[8] published a letter from the government surveyor, KM Harrisson, expressing his concern that the Tasmanian Animals' and Birds' Protection Act 1919[9] would remove the previously gazetted sanctuary. However, he may have been misinformed, since the shores of the lake were protected under the Lands Act of 1911, and not under the Game Protection Act, 1907 or its successor the Animals' and Birds' Protection Act, 1919, which dealt with species not places.

In 2005 a Crown Land Assessment and Classification (CLAC) Project report[10] advised that although there was scope for re-classification as a Nature Reserve under the Nature Conservation Act 2002:

It is recommended that the reserve not be proclaimed until, where there is no practical alternative, any necessary and suitable access points or arrangements, and impact protection measures to allow for stock watering have been identified. (CLAC Project Consultation Report and Recommendations, p. 9)

The King Island Biodiversity Management Plan 2012–2022 identified Lake Flannigan as habitat for the Orange-bellied Parrot (Neophema chrysogaster), which uses the area each year as a stop-over en route to Victoria, from mid-March to June and again briefly in September when returning.[11]

Nomenclature

The Companion to Tasmanian History summarises the evolution of the official naming of places in Tasmania.[12] It reveals that: "Until 1956 place names were applied by walking clubs and government bodies such as Mines Department, Hydro-Electric Commission and the Surveys Office. These names were loosely controlled by the Surveys Office with municipal councils responsible for street, road and park names within township boundaries."[12]

The lake has had several names, including Big Lake, Lake Dobson and Lake Flannigan.[13]

Big Lake

The present Lake Flannigan was originally called Big Lake by the islanders. A scientific group, the Field Naturalists Club of Victoria, conducted an extensive field trip to the island in 1887, and published many reports about it for the next 2 years.[14] During the trip they recorded that:[14]

To the south of Wickham lies a large lagoon, hitherto known only by the name of the big lagoon. This we renamed Lake Dobson, in honour of Dr. Dobson, to whom the exploration party was much indebted for valuable assistance in various ways.

The reference to Dr. Dobson is the Victorian politician, Frank Dobson who, in 1884, was president of the Field Naturalists Club of Victoria.[15]

The Field Naturalists must have failed to notify or convince the islanders or the Lands Department in Hobart of their new name for the lake, because the name Big Lake continued in use until 1911, as can be seen on the official Lands Department map of King Island drawn in that year.[16] On the 1911 map, the name Lake Flannigan is written over the original name of the lake, which has been erased. This was customary professional practice at the time – lithographs of maps had to do many years of service and were overwritten many times with updates, until it was deemed necessary to start afresh with a new map. Thus it appears that the lake was still known as Big Lake in 1911.

Lake Dobson

The intention of the Victorian Field Naturalists to rename King Island's Big Lake to Lake Dobson in 1887 was never implemented.

However, in 1953 the Tasmanian Tramp[17] reported that the name Lake Dobson had been officially assigned to a body of water in the Mount Field National Park on mainland Tasmania, as is shown in the Parks & Wildlife Service's Map of Mount Field National Park: . It is the namesake of Henry Dobson MHA (1841–1918), a prominent Tasmanian lawyer and politician, who founded the Tourist Association.[18]

Lake Flannigan

Although the Lands Department had no formal responsibility for naming places in Tasmania prior to 1956, several of the staff were keenly interested in nomenclature. The surveyors' field books of period are catalogued in the archives, but are not available, and the correspondence of the department does not reveal who was responsible for naming Lake Flannigan, but it may have been any or all of the following of Flannigan's colleagues:

- Hall: In 2006 Smith wrote of Hall's interest in place names: “in 1885 Leventhorpe [Michael] Hall, Chief Draftsman of the Surveys Office, drew up a list of Aboriginal words to be applied to any new towns, parishes etc.". So, even in 1911, in retirement, he may have had a part in the naming of the lake after his late colleague.[12]

- Harrisson: the obituary of the District Surveyor Kenneth Montague Harrisson records that, like MJ Flannigan, he worked on King Island and it tells of his enthusiasm for naming places as he surveyed them.[19]

- Hurst: Harrisson's colleague William Nevin Tatlow Hurst spoke and wrote in detail about the naming of Tasmania's places, especially in 1911.[20][21] Hurst was Acting Surveyor-General from May to September 1911, whilst Counsel was overseas on government business.[22] He was not only a colleague of Flannigan's but also a personal friend. Flannigan witnessed Hurst's mother's will, in 1897[23] and he named Hurst as an executor on his own will in 1901, referring to him as “my friend”.[24]

Flannigan conducted surveys on King Island several times from 1895 onwards, and bought two parcels of land there, above the Ettrick River. He was appointed as permanent District Surveyor for the island in 1899.[25] But severe ill-health forced him to leave the island in 1901. He returned to his family (his Irish mother, Margaret O'Halloran and her son from her second marriage, William Higgs) in Bendigo Victoria, and died there of tuberculosis in April 1901, aged 38.

By 1913, he had become permanently commemorated by the naming of Lake Flannigan in his honour.

The name Big Lake was transferred to a previously nameless lagoon on the edge of Colliers Swamp Conservation Area, in the southernmost locality of Surprise Bay, King Island.

Climate

Lake Flannigan has an oceanic climate (Cfb) bordering on a warm Mediterranean climate (Csb).

| Climate data for Lake Flannigan 1990–2022 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 38.5 (1.52) |

30.5 (1.20) |

39.8 (1.57) |

51.7 (2.04) |

79.7 (3.14) |

85.3 (3.36) |

104.9 (4.13) |

114.1 (4.49) |

76.8 (3.02) |

62.6 (2.46) |

49.3 (1.94) |

40.4 (1.59) |

764.5 (30.10) |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology (Climate Data Online)[26] | |||||||||||||

Water bodies on King Island

The island is very well-endowed with sources of fresh water, although some are ephemeral.

There are forty-five lakes and lagoons distributed across the island.

| A – E | G – Pi | Pj – Z |

|---|---|---|

| Attrills Lagoon | George Lagoon | Porky Lagoon |

| Bertie Lagoon | Granite Lagoon | Ridge Lagoon |

| Big Lake | Lake Flannigan | Sam Lagoon |

| Bob Lagoon (Game Reserve) | Lake Martha Lavinia | Seal Rocks Lagoon |

| Bungaree Lagoon (Conservation Area) | Lake Wickham | Shearing Shed Lagoons |

| Cask Lake | Lily Lagoon (Nature Reserve) | Snake Hole |

| Chain of Lagoons | Little Cask Lake | Stick Lagoon |

| Clevelands Lagoon | Long Lagoon | Sullivans Lagoon |

| Corduroy Lake | Manresa Lagoon | Swan Lagoon |

| Dead Sea | Meatsafe Lagoon | Tathams Lagoon (Conservation Area) |

| Deep Lagoons (Conservation Area) | Mimi Lagoon | Three Tree Lagoon |

| Denbys Lagoons | Muddy Lagoon (Nature Reserve) | Wallaby Lagoon |

| Dry Lagoon (Conservation Area) | Pearshape Lagoon | White Beach Lagoon |

| Duck Ponds | Pennys Lagoon | Woodland Lagoon |

| Egg Lagoon (drained) | Pioneer Lagoon | Yellow Rock Lagoon |

Historical photos from King Island

.jpg.webp) The Netherby was wrecked on King Island in July 1866, State Library Qld.

The Netherby was wrecked on King Island in July 1866, State Library Qld. Wickham Lighthouse and quarters, King Island. Only the lighthouse remains.

Wickham Lighthouse and quarters, King Island. Only the lighthouse remains. King Island Emu skeleton: Specimen of the extinct Dromaeus ater discovered in the Royal Zoological Museum, Florence. The Ibis, Quarterly Journal of Ornithology. Vol. I. Eighth Series 1901

King Island Emu skeleton: Specimen of the extinct Dromaeus ater discovered in the Royal Zoological Museum, Florence. The Ibis, Quarterly Journal of Ornithology. Vol. I. Eighth Series 1901 Illustration of the now extinct wombat of King Island, by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur

Illustration of the now extinct wombat of King Island, by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur Elephant seals, ‘’Dromaius novaehollandiae minor’’, on King Island in former times

Elephant seals, ‘’Dromaius novaehollandiae minor’’, on King Island in former times

References

- "Placenames Tasmania". Land Tasmania. Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- "LISTMap". Land Information system Tasmania. Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- Jennings, I. N. (March 1957). "Coastal dune lakes as exemplified from King Island, Tasmania". The Geographical Journal. 123 (1). doi:10.2307/1790724. JSTOR 1790724.

- "The island history and character", Australasian, 9 June 1888, p. 51.

- Hunter, K. (15 August 2007). "Lake Flannigan filling at last". King Island Courier. p. 5.

- Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office. "Lands and Surveys Department Correspondence: LSD 1/1/87 6741b". Report by M Flannigan, January 1896 – Covering Memo by AE Counsel.

- "The Crown Lands Act 1911: King Island: sanctuaries for wildfowl". Tasmanian Government Gazette. CXX (7425): 827. 8 May 1913.

- Harrisson, K. M. (6 July 1921). "Island Bird Sanctuaries". King Island News. p. 3.

- "The Animals' and Birds' Protection Act 1919". Tasmanian Numbered Acts. Australasian Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Crown Land Assessment and Classification Project Consultation Report and Recommendations Reservation of 20 parcels on King Island, 2005". Parks and Wildlife Tasmania: King Island. King Island Municipality. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- "King Island Biodiversity Management Plan: 2012–20" (PDF). Australian Government Department of Environment and Energy: Resource. Tasmanian Government, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- Smith, W. (2006). "Place names". Companion to Tasmanian History. University of Tasmania. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- Mather, K. (2017). "King Island's lake of many names - Lake Flannigan: points of interest from the literature". The Victorian Naturalist. 134 (6): 207–214.

- "Field Naturalists Explorations Party to King Island". The Daily Telegraph. Sydney. 1889 – via Museums Victoria Collections.

- Barrow, E. (1972). "Dobson, Frank Stanley (1835–1895)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- "Map – King Island 0D – working chart of King Island including various landholders". LINC: Tasmanian Archives and Heritage. Tasmanian Government. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- "Tasmanian Tramp" (11). Hobart Walking Club. 1953: 41–43.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Dollery, E. M. (1981). "Dobson, Henry (1841–1918)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- 'Obituary Mr K. M. Harrisson. Smithson', The Advocate (Burnie, Tasmania), 31 January 1945. p. 2.

- 'Tasmanian nomenclature: the place names of the island: a record of origins and dates', The Mercury, 15 July 1911, p. 7.

- Hurst, W N T 1898, "Tasmanian nomenclature", The surveyor: the journal of the Institute of Surveyors, Tasmania, 19 May, vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 227–231.

- "About people", The Examiner (Launceston), 8 September 1911, p. 5.

- Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, Probate Office, Tasmania, Wills and Letters of Administration 1824–1989, Will No.13992, page 2

- PROV, VF 461, Victorian Probate Office, Index to Wills, Probate and Administration Records 1841–2013, VPRS 28/P2, unit 581; File 79/266.

- "New district surveyors". The Surveyor: The Journal of the Institute of Surveyors, Tasmania. 2 (11): 291–292. 25 August 1899.

- "Monthly rainfall Lake Flannigan". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 9 December 2022.