Lake Nemi

Lake Nemi (Italian: Lago di Nemi, Latin: Nemorensis Lacus, also called Diana's Mirror, Latin: Speculum Dianae) is a small circular volcanic lake in the Alban Hills 30 km (19 mi) south of Rome in the Lazio region of Italy. It takes its name from Nemi, the largest town in the area, that overlooks it from a height.

| Lake Nemi | |

|---|---|

Panoramic view | |

Lake Nemi | |

| Location | Lazio |

| Coordinates | 41°42′44″N 12°42′09″E |

| Basin countries | Italy |

| Surface area | 1.67 km2 (0.64 sq mi) |

| Max. depth | 33 m (108 ft) |

| Surface elevation | 325 m (1,066 ft) |

It was formed in an ancient volcanic crater created at least 36,000 years ago.[1]

The lake is famous for its great sunken Roman ships built under Caligula.

Archaeology and history

From the 6th century BC, the lake and its forest were sacred to the goddess Diana Nemorensis and the site of the festival Nemoralia.[2] The sacred grove of Aricia was where a priest called the Rex Nemorensis reigned until he was killed by a challenger. The monumental sanctuary of Diana was built around 300 BC as the centre of the cult.

In Roman times up to 6 large villas lay on the rim of the crater taking advantage of the cool summer air and fine views over the lake and the sea.[3] Only one villa is known to be on the shore of the lake: the villa in the locality of Santa Maria on the western shore.

Emperors Tiberius and Caligula sailed Lake Nemi not merely to cool off in summer, but to assert themselves as Nemorenses, rulers aligning with the Stars, wedded to Earth's perpetual life-force.

Villa at Santa Maria

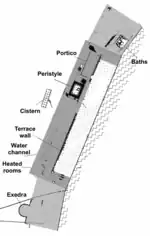

The villa was excavated between 1998 and 2002.[4] It was built in the late Republican era, mid-first century BC, and underwent 4 remodelling phases until the 120s AD. The size and quality of the villa, and the fact that it was the only one located on the lake strongly indicate that it was an imperial villa and the one in nemorensi (in Diana’s sacred wood) owned by Julius Caesar.[5] It stayed in imperial ownership probably being used as a base by Caligula.

It is situated on a large artificial terrace of which stretched 260 m along the shore with a width of 60 m and 9 m high above the lake.

The northern sector was smaller and simply decorated and was probably the living quarters for the villa’s servants. The rooms had geometric monochrome floors and a small bath suite north of the villa built in the fourth phase probably also for servants.

The central part was sumptuously decorated for "public" functions and entertainment while the southern part was for private family use. The central part was built around a large peristyle 21.3 x 13.5 m with a rich marble opus sectile floor. On the north side of this peristyle was a large triclinium overlooking the lake, also with an opus sectile floor. Surrounding the peristyle on western and southern sides were living rooms (cubicula) decorated with opus sectile floors and walls with coloured stucco.

The private wing was very richly decorated and was dominated by two large features intended for the owner's private uses: a long pool and a huge exedra, between which were the residential quarters and baths of the owner. The exedra had a semicircular main room of diameter 21 m and two wings of total 48 m width, built against the rock. Parallel to the exedra was a 1.1 m wide water channel. The long pool built in the early first century AD was over 63 m long, 4.3 m wide and 1 m deep with 0.75 m wide mortar walls was cut partly into the rock of the terrace. At its southern end was a circular pool with steps leading into the basin. It was parallel to the terrace wall with a garden between them. The channel was fed from a cistern, 34 x 8 m and height 6 m, which still exists above the villa.[6]

The emissary

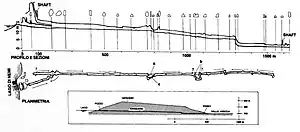

Lake Nemi, like that of Albano, has no natural outlets and all the water comes from rain in the crater. Originally the level must have greatly fluctuated. Hence the lake level was controlled from rising too high in ancient times by an emissary connected to a 1650 m-long tunnel dug through the crater wall and ending in Vallericca c. 10 m lower. It dates from before circa 300 BC when the upper inlet was closed and replaced by an entrance around 11 m lower to further reduce the level of the lake and which had a series of chambers.[7]

In planning the tunnel the shortest path from the lake to the outside was used consistent with the minimum downhill slope needed. The tunnel connects the lake with the adjacent crater of Ariccia, which was also occupied by a lake at that time and later reclaimed.

It was a monumental, if invisible, project which involved many workers not least to dispose of the excavated material and to transport it away. The original tunnel varied between 0.7 and 1 m wide meaning that only one person could be at the excavation face at a time. No intermediate shafts were used in the central part, unlike other tunnels, to speed up the work and lower the orientation error, but to set the initial direction of the tunnels at the two ends several vertical shafts were included there. Tunnelling would have started at the outlet end to avoid flooding of the workface from groundwater but when hard basalt rock was encountered tunnelling also from the inlet seems to have been added.[8]

The emissary entrance is a few metres above the current level of the lake, on the south-western shore. An 18th century portal gives access to a first stretch of tunnel clad with large opus quadratum blocks for about 25 m. A stone plate with circular holes, part of which is still in situ, was a filter to prevent entry of logs and other large debris. Grooves in the walls are clearly visible for bulkheads which could control the flow of water and allowing the filters to be cleaned. The original plan was for the entrance to be on the same level as the floor of the main tunnel but there is a steep slope from the outside to avoid water entering the tunnel while under construction. The entrance floor was to be lowered once completed but this was never done.

From the entrance a narrow tunnel leads, after about 150 m, into the trapezoidal tunnel.

After Vallericca the water flowed in an open-air channel for about 2 km before another underground section for 600 m, the so-called Aricino tunnel.

Art and literature

- Lake Nemi has been the subject for works by such artists as John Robert Cozens, George Inness, and Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes.

- Muriel Spark's 1976 novel The Takeover is set in three fictitious villas overlooking Lake Nemi.

- Lake Nemi inspired the first name of Norwegian comic character Nemi Montoya.

- The lake and its surroundings are featured in the game Assassin's Creed Brotherhood wherein the title character destroys a war machine commissioned by the work's antagonist Cesare Borgia and invented by Leonardo da Vinci.

- Mussolini led the effort to locate Caligula's devotional barges sunk 2000 years ago in Lake Nemi, see TheNYTimes April 9, 1908, then April 26, 1926, April 10, 1927, Feb 4, 1929

- Featured in Lindsey Davis' 2007 historical mystery crime novel Saturnalia (Davis novel)

See also

References

- Freda, Carmela; et al. (2006). "Eruptive history and petrologic evolution of the Albano multiple maar (Alban Hills, Central Italy)". Bulletin of Volcanology. 68 (6): 567–591. Bibcode:2006BVol...68..567F. doi:10.1007/s00445-005-0033-6

- Ovid, Fasti, trans. James George Frazer, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1931), 3:259-275

- P.Guldager Bilde, ‘Caesar’s villa? Nordic excavations of a Roman villa by Lake Nemi,loc. S.Maria (1998- 2001)’,Anal Rom 30, 2004, 7–42.

- P. BILDE The Roman villa by Lake Nemi: from nature to culture – between private and public, Proceedings of a conference at the Swedish Institute in Rome September 17-18, 2004 p 1

- Cicero Att. 6.1.25

- P. BILDE The Roman villa by Lake Nemi: from nature to culture – between private and public, Proceedings of a conference at the Swedish Institute in Rome September 17-18, 2004 p 4

- P. BILDE The Roman villa by Lake Nemi: from nature to culture – between private and public, Proceedings of a conference at the Swedish Institute in Rome September 17-18, 2004 p 7

- Emissario di nemi http://www.lambertoferriricchi.it/test2/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/pdf/NEMI.pdf