Vlasina Lake

Vlasina Lake (Serbian: Власинско језеро, romanized: Vlasinsko jezero) is a semi-artificial lake in Southeast Serbia. Lying at an altitude of 1,211 metres (3,973 ft), with an area of 16 square kilometres (6.2 sq mi), it is the highest and largest artificial lake in Serbia. It was created in 1947–51 when the peat bog Vlasinsko blato (Vlasina mud) was closed off by a dam and submerged by the waters of incoming rivers, chiefly the Vlasina.

| Vlasina Lake | |

|---|---|

| |

Vlasina Lake | |

| Location | Southeast Serbia |

| Coordinates | 42°42′N 22°20′E |

| Type | reservoir |

| Primary outflows | Vlasina River |

| Basin countries | Serbia |

| Max. length | 10.5 km (6.5 mi) |

| Max. width | 3.5 km (2.2 mi) |

| Surface area | 16 km2 (6.2 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 10.3 m (34 ft) |

| Max. depth | 34 m (112 ft) |

| Water volume | 0.165 km3 (134,000 acre⋅ft) |

| Surface elevation | 1,211 m (3,973 ft) |

| Frozen | occasionally |

| Islands | 2 permanent up to 30 floating islands |

Location

The lake lies at 42°42′N 22°20′E on a plateau called Vlasina in the municipalities of Surdulica and Crna Trava.[1]

The lake is most easily accessible from the southwestern side, by a 19 kilometres (12 mi) long section of the M1.13 road from Surdulica, which itself lies 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) east of the Niš-Skopje motorway on the E75 European Route. The road extends west, towards the Bulgarian border crossing at Strezimirovci, some 20 kilometres (12 mi) away. Along the west shore, the regional road R122 leads across the dam towards Crna Trava in the north.[2]

Geography

The plateau is surrounded by the mountains of Čemernik, Vardenik and Gramada.[3] Geological and hydrological surveys showed that lake used to existed in this area in distant history.[4] The lake runs north–south for a length of about 9.5 kilometres (5.9 mi) and has a maximum width of approximately 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi). Its average depth is 10.5 metres (34 ft) and its maximum depth is 34 metres (112 ft), near the dam.

The central part of the lake is wide and 10 and 15 metres (33 and 49 ft) deep. Its eastern coastline is jagged, with two bays: larger Biljanina bara and smaller Murin zaliv separated by Taraija peninsula. The southern part of the lake, between Bratanov del peninsula and the mouth of Božićki kanal is shallower (2 to 6 metres or 6.6 to 19.7 feet), with swampy coasts and peat.

The "working level of reservoir" is projected between the altitudes of 1,205.26 m (3,954.3 ft) and 1,213 m (3,980 ft).[5]

Islands

There are two permanent islands on the lake, along its eastern coast: Dugi Del (7.84 hectares or 19.4 acres) and Stratorija (1.82 hectares or 4.5 acres).[1] Both islands are covered with green areas and forests.[6]

Along with those islands, one of the lake's most famous features are the floating islands. They didn't exist in the former peat bog and began appearing after 1948, when the lake was created. They are formed when at high water level, loose chunks of peat 0.5 to 2 metres (1 ft 8 in to 6 ft 7 in) thick break off the shore. It is estimated that the peat chunks took 5,000 years to form. There are up to 30 floating islands at the time. Driven by the wind, they float from one shore of the lake to another, carrying the flora and fauna, and serving as shelter and a food source for fish. For that reason, they are an attractive target for fishermen, however it is forbidden to visit them or disturb them because of the unique animal and plant ecosystems, though walking on them is practically impossible since they don't have solid ground.[5][6]

The largest such island has an area of 2 hectares (4.9 acres), it is referred to as "Moby-Dick" by the local population, and is the largest such formation in the Balkans. It is overgrown with dense vegetation, including birch trees. Carried by the water currents and strong winds, in 2016 "Moby-Dick" almost reached the shore near the "Vlasina" hotel, softly attaching itself to the bank and becoming a major tourist attraction. Previous such occurrence happened in the mid-1990s. During the extremely low water level, it was reported in August 2018 that the island was partially stranded on dry ground. Another major storm and strong wind, detached Moby-Dick on 15 August 2020, which after four years continued to float on the lake surface.[5]

Water

The temperature of the water reaches 21 to 23 °C (70 to 73 °F) in the summer months,[7] making for refreshing swimming. It freezes in the winter and the ice crust can be as much as 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) thick.[8] The temperature also varies with location and depth. In the village of Topli Dol south of the lake, there is a water factory "Vlasinka", producing high-quality mineral water called "Vlasinska Rosa", a renowned brand in Serbia. It was purchased by The Coca-Cola Company in 2005.[9]

There are some 70 natural water springs in the lake area. The best known kladenac (cold water spring), noted for its cold water and most visited by the tourists, is the Sveti Nikola (Saint Nicholas) spring.[5]

Dams

The dam is located in the northwestern part of the lake. It is an embankment dam, built of a concrete core with an earth-filled cover. First plans for the power plant were made in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, during the Interbellum.[10] Construction ran from 1946 to 1948, when the reservoir was first filled. It is 239 metres (784 ft) long, 139 metres (456 ft) wide at the base and 5.5 metres (18 ft) at the top, and 34 metres (112 ft) high (of which 25.7 metres or 84 feet is above the ground). The reservoir it creates has a volume of around 1.65 cubic kilometres (0.40 cu mi). Of these, 1.05 cubic kilometres (0.25 cu mi) is usable for hydroelectric exploitation.[5] The system of 4 hydroelectric plants called Vrla (I-IV) lies downstream of the lake, on the Vrla River, with a total capacity of 125 megawatt-hours (450 GJ).[11] A part of the hydroelectric system is the pump station "Lisina", which pumps in water from the nearby Lisina Lake, chiefly in summer months. Vlasina Lake is also fed by numerous streams, descending from the surrounding mountains. The water level varies, depending on the water influx and drainage of the dam. Two artificial canals enter the lake near the dam: Čemernički kanal from the west and Strvna from east.

The construction of the entire Vrla complex of 4 power plants was finished in 1958. The water from another artificial lake, Lisina, on the Božička Reka, is being partially rerouted into the lakes watershed. As the Božička Reka is the longer headstream of the Dragovištica, which in turn flows into the Struma in Bulgaria which empties into the Aegean Sea in Greece. As the lake, via its outflow Vlasina, belongs to the Black Sea drainage basin, this way the artificial bifurcation was created.[5]

Biodiversity and protection

Flora and fauna of the lake, and the entire surrounding Vlasina region, are rich, and include several endemic species. It features over 850 species of flora and over 180 species of vertebrates, including rare species of mammals, reptiles and amphibians.[1]

Plants

The lake's surroundings are a mixture of meadows and high-altitude forests, especially birch, beech, pine and juniper (the former two indigenous, and the latter chiefly introduced by afforestation of the western shore). The indigenous trees downy birch and yellow beech (characteristic for its ever-yellow leaf color) stand out among the species of trees.[3]

Sundew is the only carnivorous plant in Serbia and is unique to the Vlasina region.[3] It is estimated that over 300 herbal species in the region are medicinal.[5]

Animals

The lake is home to 16 species of fish.[10] These include:[5] Brown Trout, Ohrid trout, Rainbow trout, European perch, European eel, Eurasian minnow, Mediterranean barbel, grass carp, common carp, crucian carp, Prussian carp, tench, roach, common chub, pumpkinseed and others. Ohrid trout was stocked and it successfully adapted to the environment, making it a popular for fishing.

Birds includes gray heron, mallard, tufted duck and cormorant.[3] Mammalian species include wild boars, wolves, foxes, hares, roe deer and feral horses.[10]

Protection

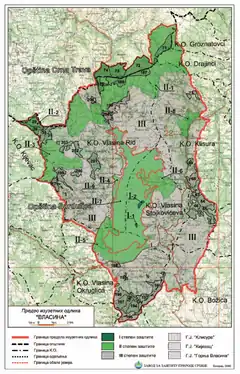

By the decision of Government of Serbia in 2006, the Vlasina region is protected as a nature preserve of special interest at category I. The total protected area is 12,741 hectares (31,480 acres), of which 9.6 hectares (24 acres) are in the 1st level of protection (islands of Dugi Del and Stratorija), 4,354 hectares (10,760 acres) in the 2nd level and 8,377 hectares (20,700 acres) in the 3rd level of protection.[1]

2018 water level fluctuation

In the summer of 2018, both the citizens and the tourists, so as the administration of the Surdulica municipality reported the record low water level in the lake. Municipality issued a statement saying that the sudden water discharge at the dam may destroy the part of the plant and animal life in the lake. Numerous boats and barges were stranded, such as the "Moby-Dick", the largest floating island on the lake. It is estimated that the level fell for up to 5 m (16 ft). The Elektroprivreda Srbije (EPS), a state-owned electric utility power company admitted that they are forced to discharge larger amounts of water from the lake because of the repairs on one of the four Vrla hydro power plants, but that no harm will be done. The reconstructed power plant, Vrla I, was built in 1955 and it was stated that the renovation "was necessary" and that the works will be finished by October 2018.[5]

By October other floating islands got stranded, the boat traffic was made more difficult and the water level dropped by 4 to 7 m (13 to 23 ft). In the shallower bays the water receded significantly and they have been described as "desolate". The EPS claimed that the works will last for only 30 days and that water level has to be reduced to 1,206.5 m (3,958 ft) but continued to claim that no harm will be done. University of Belgrade Geography Faculty contradicted the company's claim. The longer floating island are stranded, the greater is the chance that they will not "unhinge" from the bank when the water rises. Head of the local protection enterprise accused EPS of lowering the water level to produce more electricity rather than to renovate the plant. The EPS stated that "in the period to come", they will start to pump the water from the Lisine Lake into the Vlasina.[12]

Tourism

Current tourist capacity includes around 300 beds in hotels "Vlasina" and "Narcis", offering a modest range of services.[13] There is a youth resort, Omladinsko Naselje, at the lake, with over 200 beds. It has not been maintained for a while, though in 2019 and 2021 its full renovation was announced.[14][15] Along with regular tourists, they often host sporting teams from Serbia and abroad, as the lake is a popular destination for summer training due to its high altitude. Sporting grounds include a large football field, small sports field and weightlifting room.

Touristic attractions could include the numerous churches from the 19th century in the area. Also, the region is known for many popular local legends, which include myths of the giant water beasts, fairies and the now submerged bridge which was allegedly built by the Crusaders on their way to Jerusalem.[10]

An ambitious project for development of tourism is planned for the Vlasina area by the country's Development plan and the Ministry of Tourism, and it is included in the 2005 "21 projects for the 21st century" plan. The planned facilities include a new tourist center Novi Rid, with 1,000 beds and shopping center, tourist center Krstinci with 350 beds, center "Džukelice" for summer sports, a marina for sailboats (motorboats are forbidden on the lake), a number of ski lifts and facilities for Nordic skiing. By this plan, by 2021 Vlasina was to get a heliport and an airfield for smaller airplanes.[8]

Nothing of this happened, and in 2022 another ambitious plan for the neglected tourism center was announced, which would include an investment of €500 million and 10,000 new jobs. Announced as the "eco-icon of Europe", the project was to follow the strictest ecological rules. More or less, the same attractions and structures were planned, as per the 2005 plan. Local ecological groups doubted such a massive and expensive project, especially at such high standards, will be done.[16]

Gallery

|

See also

References

- Ministry of Environmental Protection of Republic of Serbia (2006-04-11). "Uredba o zaštiti Predela izuzetnih odlika "Vlasina"" (PDF) (in Serbian). Official Gazette of Republic of Serbia.

- "Serbia Main and Regional Road network map" (PDF). Public Utility "Roads of Serbia".

- "Vlasinsko jezero" (in Serbian). Turistička organizacija Srbije. Archived from the original on 2007-05-07. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- Да ли знате - Које је највеће акумулационо језеро у Србији? [Did you know - What is the largest accumulation lake in Serbia?]. Politika (in Serbian). 9 October 2019. p. 30.

- Danilo Kocić (22 August 2018). "Ugroženo najveće plutajuće tresetno ostrvo na Balkanu" [The largest floating peat island in the Balkans is endangered]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 13.

- Danilo Kocić (20 August 2020). Власинским језермо слободно плута Моби Дик [Moby Dick floating freely on Vlasina Lake]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 20.

- "Klub putnika Srbije:Vlasinsko jezero" (in Serbian).

- Žaklina Milenković (2005-02-21). "Ploveća ostrva - svetski fenomen" (in Serbian). Glas javnosti.

- "Serbian president attends takeover of "Vlasinka"". Tanjug. 2005-06-06.

- Tanja Vujić (23 June 2009), "Vlasina nije za snobove", Politika (in Serbian)

- "Economic Association "Hydro Power Plants Djerdap", plc". Elektroprivreda Srbije. Archived from the original on 2011-04-06. Retrieved 2010-10-19.

- Danilo Kocić (4 October 2018). "EPS drastično spustio nivo Vlasinskog jezera" [EPS drastically lowered the water level in the Vlasina Lake]. Politika (in Serbian).

- "Nastava u prirodi: Vlasinsko jezero" (in Serbian). Unico Travel agency. Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- Danilo Kocić (29 October 2021). "Počinje obnova Omladinskog naselja kraj Vlasinskog jezera" [Reconstruction of the Youth Resort at Lake Vlasina begins]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 12.

- M.Mitić (22 October 2021). "Ponovo najavljena rekonstrukcija Omladinskog naselja na Vlasinskom jezeru" [Reconstruction of the Youth Resort at Lake Vlasina announced again]. Južne vesti (in Serbian).

- Toma Todorović (24 July 2022). Очување животне средине предуслов за грађевински бум [Preservation of nature a condition for construction boom]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.