Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome

Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by muscle weakness of the limbs.

| Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Lambert–Eaton syndrome, Eaton–Lambert syndrome |

| |

| Neuromuscular junction. Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome is caused by autoantibodies to the presynaptic membrane. Myasthenia gravis is caused by autoantibodies to the postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors. | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Frequency | 3.4 per million people[1] |

Around 60% of those with LEMS have an underlying malignancy, most commonly small-cell lung cancer; it is therefore regarded as a paraneoplastic syndrome (a condition that arises as a result of cancer elsewhere in the body).[2] It is the result of antibodies against presynaptic voltage-gated calcium channels, and likely other nerve terminal proteins, in the neuromuscular junction (the connection between nerves and the muscle that they supply).[3] The diagnosis is usually confirmed with electromyography and blood tests; these also distinguish it from myasthenia gravis, a related autoimmune neuromuscular disease.[3]

If the disease is associated with cancer, direct treatment of the cancer often relieves the symptoms of LEMS. Other treatments often used are steroids, azathioprine, which suppress the immune system, intravenous immunoglobulin, which outcompetes autoreactive antibody for Fc receptors, and pyridostigmine and 3,4-diaminopyridine, which enhance the neuromuscular transmission. Occasionally, plasma exchange is required to remove the antibodies.[3]

The condition affects about 3.4 per million people.[1] LEMS usually occurs in people over 40 years of age, but may occur at any age.

Signs and symptoms

The weakness from LEMS typically involves the muscles of the proximal arms and legs (the muscles closer to the trunk). In contrast to myasthenia gravis, the weakness affects the legs more than the arms. This leads to difficulties climbing stairs and rising from a sitting position. Weakness is often relieved temporarily after exertion or physical exercise. High temperatures can worsen the symptoms. Weakness of the bulbar muscles (muscles of the mouth and throat) is occasionally encountered.[3] Weakness of the eye muscles is uncommon. Some may have double vision, drooping of the eyelids and difficulty swallowing,[3] but generally only together with leg weakness; this too distinguishes LEMS from myasthenia gravis, in which eye signs are much more common.[2] In the advanced stages of the disease, weakness of the respiratory muscles may occur.[3] Some may also experience problems with coordination (ataxia).[4]

Three-quarters of people with LEMS also have disruption of the autonomic nervous system. This may be experienced as a dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, impaired sweating, and orthostatic hypotension (falls in blood pressure on standing, potentially leading to blackouts). Some report a metallic taste in the mouth.[3]

On neurological examination, the weakness demonstrated with normal testing of power is often less severe than would be expected on the basis of the symptoms. Strength improves further with repeated testing, e.g. improvement of power on repeated hand grip (a phenomenon known as "Lambert's sign"). At rest, reflexes are typically reduced; with muscle use, reflex strength increases. This is a characteristic feature of LEMS. The pupillary light reflex may be sluggish.[3]

In LEMS associated with lung cancer, most have no suggestive symptoms of cancer at the time, such as cough, coughing blood, and unintentional weight loss.[2] LEMS associated with lung cancer may be more severe.[4]

Causes

LEMS is often associated with lung cancer (50–70%), specifically small-cell carcinoma,[3] making LEMS a paraneoplastic syndrome.[4] Of the people with small-cell lung cancer, 1–3% have LEMS.[2] In most of these cases, LEMS is the first symptom of the lung cancer, and it is otherwise asymptomatic.[2]

LEMS may also be associated with endocrine diseases, such as hypothyroidism (an underactive thyroid gland) or diabetes mellitus type 1.[3][5] Myasthenia gravis, too, may happen in the presence of tumors (thymoma, a tumor of the thymus in the chest); people with MG without a tumor and people with LEMS without a tumor have similar genetic variations that seem to predispose them to these diseases.[2] HLA-DR3-B8 (an HLA subtype), in particular, seems to predispose to LEMS.[5]

Mechanism

In normal neuromuscular function, a nerve impulse is carried down the axon (the long projection of a nerve cell) from the spinal cord. At the nerve ending in the neuromuscular junction, where the impulse is transferred to the muscle cell, the nerve impulse leads to the opening of voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCC), the influx of calcium ions into the nerve terminal, and the calcium-dependent triggering of synaptic vesicle fusion with plasma membrane. These synaptic vesicles contain acetylcholine, which is released into the synaptic cleft and stimulates the acetylcholine receptors on the muscle. The muscle then contracts.[3]

In LEMS, antibodies against VGCC, particularly the P/Q-type VGCC, decrease the amount of calcium that can enter the nerve ending, hence less acetylcholine can be released from the neuromuscular junction. Apart from skeletal muscle, the autonomic nervous system also requires acetylcholine neurotransmission; this explains the occurrence of autonomic symptoms in LEMS.[3][2] P/Q voltage-gated calcium channels are also found in the cerebellum, explaining why some experience problems with coordination.[4][5] The antibodies bind particularly to the part of the receptor known as the "domain III S5–S6 linker peptide".[5] Antibodies may also bind other VGCCs.[5] Some have antibodies that bind synaptotagmin, the protein sensor for calcium-regulated vesicle fusion.[5] Many people with LEMS, both with and without VGCC antibodies, have detectable antibodies against the M1 subtype of the acetylcholine receptor; their presence may participate in a lack of compensation for the weak calcium influx.[5]

Apart from the decreased calcium influx, a disruption of active zone vesicle release sites also occurs, which may also be antibody-dependent, since people with LEMS have antibodies to components of these active zones (including voltage-dependent calcium channels). Together, these abnormalities lead to the decrease in muscle contractility. Repeated stimuli over a period of about 10 seconds eventually lead to sufficient delivery of calcium, and an increase in muscle contraction to normal levels, which can be demonstrated using an electrodiagnostic medicine study called needle electromyography by increasing amplitude of repeated compound muscle action potentials.[3]

The antibodies found in LEMS associated with lung cancer also bind to calcium channels in the cancer cells, and it is presumed that the antibodies originally develop as a reaction to these cells.[3] It has been suggested that the immune reaction to the cancer cells suppresses their growth and improves the prognosis from the cancer.[2][5]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually made with nerve conduction study (NCS) and electromyography (EMG), which is one of the standard tests in the investigation of otherwise unexplained muscle weakness. EMG involves the insertion of small needles into the muscles. NCS involves administering small electrical impulses to the nerves, on the surface of the skin, and measuring the electrical response of the muscle in question. NCS investigation in LEMS primarily involves evaluation of compound motor action potentials (CMAPs) of effected muscles and sometimes EMG single-fiber examination can be used.[3]

CMAPs show small amplitudes but normal latency and conduction velocities. If repeated impulses are administered (2 per second or 2 Hz), it is normal for CMAP amplitudes to become smaller as the acetylcholine in the motor end plate is depleted. In LEMS, this decrease is larger than observed normally. Eventually, stored acetylcholine is made available, and the amplitudes increase again. In LEMS, this remains insufficient to reach a level sufficient for transmission of an impulse from nerve to muscle; all can be attributed to insufficient calcium in the nerve terminal. A similar pattern is witnessed in myasthenia gravis. In LEMS, in response to exercising the muscle, the CMAP amplitude increases greatly (over 200%, often much more). This also occurs on the administration of a rapid burst of electrical stimuli (20 impulses per second for 10 seconds). This is attributed to the influx of calcium in response to these stimuli.[3][2] On single-fiber examination, features may include increased jitter (seen in other diseases of neuromuscular transmission) and blocking.[3]

Blood tests may be performed to exclude other causes of muscle disease (elevated creatine kinase may indicate a myositis, and abnormal thyroid function tests may indicate thyrotoxic myopathy). Antibodies against voltage-gated calcium channels can be identified in 85% of people with EMG-confirmed LEMS.[3] Once LEMS is diagnosed, investigations such as a CT scan of the chest are usually performed to identify any possible underlying lung tumors. Around 50–60% of these are discovered immediately after the diagnosis of LEMS. The remainder is diagnosed later, but usually within two years and typically within four years.[2] As a result, scans are typically repeated every six months for the first two years after diagnosis.[3] While CT of the lungs is usually adequate, a positron emission tomography scan of the body may also be performed to search for an occult tumour, particularly of the lung.[6]

Treatment

If LEMS is caused by an underlying cancer, treatment of the cancer usually leads to resolution of the symptoms.[3] Treatment usually consists of chemotherapy, with radiation therapy in those with limited disease.[2]

Immunosuppression

Some evidence supports the use of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG).[7] Immune suppression tends to be less effective than in other autoimmune diseases. Prednisolone (a glucocorticoid or steroid) suppresses the immune response, and the steroid-sparing agent azathioprine may replace it once therapeutic effect has been achieved. IVIG may be used with a degree of effectiveness. Plasma exchange (or plasmapheresis), the removal of plasma proteins such as antibodies and replacement with normal plasma, may provide improvement in acute severe weakness. Again, plasma exchange is less effective than in other related conditions such as myasthenia gravis, and additional immunosuppressive medication is often needed.[3]

Other

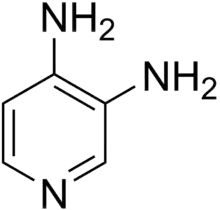

Three other treatment modalities also aim at improving LEMS symptoms, namely pyridostigmine, 3,4-diaminopyridine (amifampridine), and guanidine. They work to improve neuromuscular transmission.

Tentative evidence supports 3,4-diaminopyridine at least for a few weeks.[7] The 3,4-diaminopyridine base or the water-soluble 3,4-diaminopyridine phosphate may be used.[8] Both 3,4-diaminopyridine formulations delay the repolarization of nerve terminals after a discharge, thereby allowing more calcium to accumulate in the nerve terminal.[3][2]

Pyridostigmine decreases the degradation of acetylcholine after release into the synaptic cleft, and thereby improves muscle contraction. An older agent, guanidine, causes many side effects and is not recommended. 4-Aminopyridine (dalfampridine), an agent related to 3,4-aminopyridine, causes more side effects than 3,4-DAP and is also not recommended.[2]

The FDA approved amifampridine for use in children 6 years and older with LEMS in addition to the prior approval for use in adults with LEMS on November 28, 2018.[9]

History

Anderson and colleagues from St Thomas' Hospital, London, were the first to mention a case with possible clinical findings of LEMS in 1953,[10] but Edward H. Lambert, Lee Eaton, and E.D. Rooke at the Mayo Clinic were the first physicians to substantially describe the clinical and electrophysiological findings of the disease in 1956.[11][12] In 1972, the clustering of LEMS with other autoimmune diseases led to the hypothesis that it was caused by autoimmunity.[13] Studies in the 1980s confirmed the autoimmune nature,[5] and research in the 1990s demonstrated the link with antibodies against P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channels.[3][14]

References

- Titulaer MJ, Lang B, Verschuuren JJ (December 2011). "Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome: from clinical characteristics to therapeutic strategies". Lancet Neurol. 10 (12): 1098–107. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70245-9. PMID 22094130. S2CID 27421424.

- Verschuuren JJ, Wirtz PW, Titulaer MJ, Willems LN, van Gerven J (July 2006). "Available treatment options for the management of Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome". Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 7 (10): 1323–36. doi:10.1517/14656566.7.10.1323. PMID 16805718. S2CID 31331519.

- Mareska M, Gutmann L (June 2004). "Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome". Semin. Neurol. 24 (2): 149–53. doi:10.1055/s-2004-830900. PMID 15257511. S2CID 19329757.

- Rees JH (June 2004). "Paraneoplastic syndromes: when to suspect, how to confirm, and how to manage". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 75 (Suppl 2): ii43–50. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2004.040378. PMC 1765657. PMID 15146039.

- Takamori M (September 2008). "Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome: search for alternative autoimmune targets and possible compensatory mechanisms based on presynaptic calcium homeostasis". J. Neuroimmunol. 201–202: 145–52. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.04.040. PMID 18653248. S2CID 23814568.

- Ropper AH, Brown RH (2005). "53. Myasthenia Gravis and Related Disorders of the Neuromuscular Junction". In Ropper AH, Brown RH (eds.). Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 1261. ISBN 0-07-141620-X.

- Keogh, M; Sedehizadeh, S; Maddison, P (16 February 2011). "Treatment for Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (2): CD003279. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003279.pub3. PMC 7003613. PMID 21328260.

- Lindquist, S; Stangel, M; Ullah, I (2011). "Update on treatment options for Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome: focus on use of amifampridine". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 7: 341–9. doi:10.2147/NDT.S10464. PMC 3148925. PMID 21822385.

- "Firdapse (amifampridine phosphate) FDA Approval History". Drugs.com. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

- Anderson HJ, Churchill-Davidson HC, Richardson AT (December 1953). "Bronchial neoplasm with myasthenia; prolonged apnoea after administration of succinylcholine". Lancet. 265 (6799): 1291–3. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(53)91358-0. PMID 13110148.

- Lambert-Eaton-Rooke syndrome at Who Named It?

- Lambert EH, Eaton LM, Rooke ED (1956). "Defect of neuromuscular conduction associated with malignant neoplasms". Am. J. Physiol. 187: 612–613.

- Gutmann L, Crosby TW, Takamori M, Martin JD (September 1972). "The Eaton–Lambert syndrome and autoimmune disorders". Am. J. Med. 53 (3): 354–6. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(72)90179-9. PMID 4115499.

- Motomura M, Hamasaki S, Nakane S, Fukuda T, Nakao YK (August 2000). "Apheresis treatment in Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome". Ther. Apher. 4 (4): 287–90. doi:10.1046/j.1526-0968.2000.004004287.x. PMID 10975475.