History of Latin America

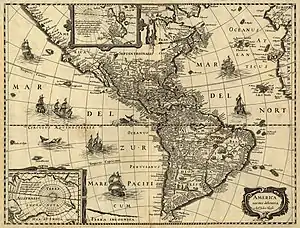

The term Latin America primarily refers to the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking countries in the New World.

Before the arrival of Europeans in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, the region was home to many indigenous peoples, a number of which had advanced civilizations, most notably from South; the Olmec, Maya, Muisca and Inca.

The region came under control of the crowns of Spain and Portugal, which imposed both Roman Catholicism and their respective languages. Both the Spanish and the Portuguese brought African slaves to their colonies, as laborers, particularly in regions where indigenous populations who could be made to work were absent.

In the early nineteenth century nearly all of areas of Spanish America attained independence by armed struggle, with the exceptions of Cuba and Puerto Rico. Brazil, which had become a monarchy separate from Portugal, became a republic in the late nineteenth century. Political independence from European monarchies did not result in the abolition of black slavery in the new sovereign nations. Political independence resulted in political and economic instability in Spanish America immediately after independence. Great Britain and the United States exercised significant influence in the post-independence era, resulting in a form of neo-colonialism, whereby a country's political sovereignty remained in place, but foreign powers exercised considerable power in the economic sphere.

Origin of the term and definition

The idea that a part of the Americas has a cultural or racial affinity with all Romance cultures can be traced back to the 1830s, in particular in the writing of the French Saint-Simonian Michel Chevalier, who postulated that this part of the Americas were inhabited by people of a "Latin race," and that it could, therefore, ally itself with "Latin Europe" in a struggle with "Teutonic Europe," "Anglo-Saxon America" and "Slavic Europe."[1] The idea was later taken up by Latin American intellectuals and political leaders of the mid- and late-nineteenth century, who no longer looked to Spain or Portugal as cultural models, but rather to France.[2] The actual term "Latin America" was coined in France under Napoleon III and played a role in his campaign to imply cultural kinship with France, transform France into a cultural and political leader of the area and install Maximilian as emperor of Mexico.[3]

In the mid-twentieth century, especially in the United States, there was a trend to occasionally classify all of the territory south of the United States as "Latin America," especially when the discussion focused on its contemporary political and economic relations to the rest of the world, rather than solely on its cultural aspects.[4] Concurrently, there has been a move to avoid this oversimplification by talking about "Latin America and the Caribbean," as in the United Nations geoscheme.

Since, the concept and definitions of Latin American are very modern, going back only to the nineteenth century, it is anachronistic to talk about "a history of Latin America" before the arrival of the Europeans. Nevertheless, the many and varied cultures that did exist in the pre-Columbian period had a strong and direct influence on the societies that emerged as a result of the conquest, and therefore, they cannot be overlooked. They are introduced in the next section.

The Pre-Columbian period

What is now Latin America has been populated for several millennia, possibly for as long as 30,000 years. There are many models of migration to the New World. Precise dating of many of the early civilizations is difficult because there are few text sources. However, highly developed civilizations flourished at various times and places, such as in the Andes and Mesoamerica.

Sport in Pre-Columbian Period

As a result of imperialism and colonialism, historians note the diffusion of sports that brought football, baseball, boxing, cricket, and basketball from the empires to its colonies. In the context of Latin America, historians can acknowledge the power imbalances between the colonial elite and those of poorer circumstance by looking at sport history. For instance, dating back to the pre-columbian Mesoamerica, horsemanship contests were an integral part of leisure activity for the individuals of the colonies. However, many colonial official took advantage of their power over the poor people's accessibility to the game by preventing the poorer individuals from accessing the horses. This attempt to control and manipulate the people of the colony failed as many of the indigenous people needed the horses for labor– labor that would serve to benefit the upper class who exploit the colony.

Furthermore, horses played an important role in the early day of Latin American sport. Such examples include the horsemanship contests mentioned above, the charreada of Mexico, other equestrian activities in the region that would eventually be Argentina and Uruguay, etc. These sport gave the indigenous people the opportunity to practice values of talent, honor, and teamwork. It also was accessible to the poorer indigenous individuals of the colony because horses were affordable and not relatively expensive to the people of a lower class than those colonial elite.[5]

Colonial Era

Christopher Columbus landed in the Americas in 1492. Subsequently, the major sea powers in Europe sent expeditions to the New World to build trade networks and colonies and to convert the native peoples to Christianity. Spain concentrated on building its empire on the central and southern parts of the Americas allotted to it by the Treaty of Tordesillas, because of presence of large, settled societies like the Aztec, the Inca, the Maya and the Muisca, whose human and material resources it could exploit, and large concentrations of silver and gold. The Portuguese built their empire in Brazil, which fell in their sphere of influence owing to the Treaty of Tordesillas, by developing the land for sugar production since there was a lack of a large, complex society or mineral resources.

During the European colonization of the western hemisphere, most of the native population died, mainly by disease. In what has come to be known as the Columbian exchange, diseases such as smallpox and measles decimated populations with no immunity. The size of the indigenous populations has been studied in the modern era by historians,[6][7][8] but Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas raised the alarm in the earliest days of Spanish settlement in the Caribbean in his A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies.

The conquerors and colonists of Latin America also had a major impact on the population of Latin America. The Spanish conquistadors committed savage acts of violence against the natives. According to Bartolomé de las Casas, the Europeans worked the native population to death, separated the men and the women so they could not reproduce, and hunted down and killed any natives who escaped with dogs. Las Casas claimed that the Spaniards made the natives work day and night in mines and would "test the sharpness of their blades"[9] on the natives. Las Casas estimated that around three million natives died from war, slavery, and overworking. When talking about the cruelty, Las Casas said "Who in future generations will believe this? I myself writing it as a knowledgeable eyewitness can hardly believe it."

Because the Spanish were now in power, native culture and religion were forbidden. The Spanish even went as far as burning the Maya Codices (like books). These codices contained information about astrology, religion, Gods, and rituals. There are four codices known to exist today; these are the Dresden Codex, Paris Codex, Madrid Codex, and HI Codex.[10] The Spanish also melted down countless pieces of golden artwork so they could bring the gold back to Spain and destroyed countless pieces of art that they viewed as unchristian.

Colonial-era religion

- Traveling to the New World

The Spanish Crown regulated immigration to its overseas colonies, with travelers required to register with the House of Trade in Seville. Since the crown wished to exclude anyone who was non-Christian (Jews, crypto-Jews, and Muslims) passing as Christian, travelers' backgrounds were vetted. The ability to regulate the flow of people enabled the Spanish Crown to keep a grip on the religious purity of its overseas empire. The Spanish Crown was rigorous in their attempt to allow only Christians passage to the New World and required proof of religion by way of personal testimonies. Specific examples of individuals dealing with the Crown allow for an understanding of how religion affected passage into the New World.

Francisca de Figueroa, an African-Iberian woman seeking entrance into the Americas, petitioned the Spanish Crown in 1600 in order to gain a license to sail to Cartagena.[11] On her behalf she had a witness attest to her religious purity, Elvira de Medina wrote, "this witness knows that she and parents and her grandparents have been and are Old Christians and of unsullied cast and lineage. They are not of Moorish or Jewish caste or of those recently converted to Our Holy Catholic Faith."[12] Despite Francisca's race, she was allowed entrance into the Americas in 1601 when a 'Decree from His Majesty' was presented, it read, "My presidents and official judges of the Case de Contraction of Seville. I order you to allow passage to the Province of Cartagena for Francisca de Figueroa ..."[13] This example points to the importance of religion, when attempting to travel to the Americas during colonial times. Individuals had to work within the guidelines of Christianity in order to appeal to the Crown and be granted access to travel.

- Religion in Latin America

Once in the New World, religion was still a prevalent issue which had to be considered in everyday life. Many of the laws were based on religious beliefs and traditions and often these laws clashed with the many other cultures throughout colonial Latin America. One of the central clashes was between African and Iberian cultures; this difference in culture resulted in the aggressive prosecution of witches, both African and Iberian, throughout Latin America. According to European tradition "[a] witch – a bruja – was thought to reject God and the sacraments and instead worship the devil and observe the witches' Sabbath."[14] This rejection of God was seen as an abomination and was not tolerated by the authorities either in Spain nor Latin America. A specific example, the trial of Paula de Eguiluz, shows how an appeal to Christianity can help to lessen punishment even in the case of a witch trial.

Paula de Eguiluz was a woman of African descent who was born in Santo Domingo and grew up as a slave, sometime in her youth she learned the trade of witches and was publicly known to be a sorceress. "In 1623, Paula was accused of witchcraft (brujeria), divination and apostasy (declarations contrary to Church doctrine)."[15] Paula was tried in 1624 and began her hearings without much knowledge of the Crowns way of conducting legal proceedings. There needed to be appeals to Christianity and announcements of faith if an individual hoped to lessen the sentence. Learning quickly, Paula correctly "recited the Lord's Prayer, the Creed, the Salve Regina, and the Ten Commandments" before the second hearing of her trial. Finally, in the third hearing of the trial Paula ended her testimony by "ask[ing] Our Lord to forgive [me] for these dreadful sins and errors and requests ... a merciful punishment."[16] The appeals to Christianity and profession of faith allowed Paula to return to her previous life as a slave with minimal punishment. The Spanish Crown placed a high importance on the preservation of Christianity in Latin America, this preservation of Christianity allowed colonialism to rule Latin America for over three hundred years.

Nineteenth-century revolutions: the postcolonial era

Following the model of the American and French revolutions, most of Latin America achieved its independence by 1825. Independence destroyed the old common market that existed under the Spanish Empire after the Bourbon Reforms and created an increased dependence on the financial investment provided by nations, which had already begun to industrialize; therefore, Western European powers, in particular Great Britain and France, and the United States began to play major roles, since the region became economically dependent on these nations. Independence also created a new, self-consciously "Latin American" ruling class and intelligentsia, which at times avoided Spanish and Portuguese models in their quest to reshape their societies. This elite looked towards other Catholic European models—in particular France—for a new Latin American culture, but did not seek input from indigenous peoples.

The failed efforts in Spanish America to keep together most of the initial large states that emerged from independence— Gran Colombia, the Federal Republic of Central America[17] and the United Provinces of South America—resulted a number of domestic and interstate conflicts, which plagued the new countries. Brazil, in contrast to its Hispanic neighbors, remained a united monarchy and avoided the problem of civil and interstate wars. Domestic wars were often fights between federalists and centrists, who ended up asserting themselves through the military repression of their opponents at the expense of civilian political life. The new nations inherited the cultural diversity of the colonial era and strived to create a new identity based around the shared European (Spanish or Portuguese) language and culture. Within each country, however, there were cultural and class divisions that created tension and hurt national unity.

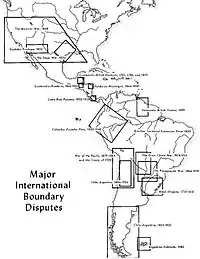

For the next few decades there was a long process to create a sense of nationality. Most of the new national borders were created around the often centuries-old audiencia jurisdictions or the Bourbon intendancies, which had become areas of political identity. In many areas the borders were unstable, since the new states fought wars with each other to gain access to resources, especially in the second half of the nineteenth century. The more important conflicts were the Paraguayan War (1864–70; also known as the War of the Triple Alliance) and the War of the Pacific (1879–84). The Paraguayan War pitted Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay against Paraguay, which was utterly defeated. As a result, Paraguay suffered a demographic collapse: the population went from an estimated 525,000 persons in 1864 to 221,000 in 1871 and out of this last population, only around 28,000 were men. In the War of the Pacific, Chile defeated the combined forces of Bolivia and Peru. Chile gained control of saltpeter-rich areas, previously controlled by Peru and Bolivia, and Bolivia became a land-locked nation. By mid-century the region also confronted a growing United States, seeking to expand on the North American continent and extend its influence in the hemisphere. In Mexican–American War (1846–48), Mexico lost over half of its territory to the United States. In the 1860s France attempted to indirectly control Mexico. In South America, Brazil consolidated its control of large swaths of the Amazon Basin at the expense of its neighbors. In the 1880s the United States implemented an aggressive policy to defend and expand its political and economic interests in all of Latin America, which culminated in the creation of the Pan-American Conference, the successful completion of the Panama Canal and the United States intervention in the final Cuban war of independence.

The export of natural resources provided the basis of most Latin American economies in the nineteenth century, which allowed for the development of wealthy elite. The restructuring of colonial economic and political realities resulted in a sizable gap between rich and poor, with landed elites controlling the vast majority of land and resources. In Brazil, for instance, by 1910 85% of the land belonged to 1% of the population. Gold mining and fruit growing, in particular, were monopolized by these wealthy landowners. These "Great Owners" completely controlled local activity and, furthermore, were the principal employers and the main source of wages. This led to a society of peasants whose connection to larger political realities remained in thrall to farming and mining magnates.

The endemic political instability and the nature of the economy resulted in the emergence of caudillos, military chiefs whose hold on power depended on their military skill and ability to dispense patronage. The political regimes were at least in theory democratic and took the form of either presidential or parliamentary governments. Both were prone to being taken over by a caudillo or an oligarchy. The political landscape was occupied by conservatives, who believed that the preservation of the old social hierarchies served as the best guarantee of national stability and prosperity, and liberals, who sought to bring about progress by freeing up the economy and individual initiative. Popular insurrections were often influential and repressed: 100,000 were killed during the suppression of a Colombian revolt between 1899 and 1902 during the Thousand Days' War. Some states did manage to have some of democracy: Uruguay, and partially Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica and Colombia. The others were clearly oligarchist or authoritarian, although these oligarchs and caudillos sometimes enjoyed support from a majority in the population. All of these regimes sought to maintain Latin America's lucrative position in the world economy as a provider of raw materials.

20th century

1900–1929

By the start of the century, the United States continued its interventionist attitude, which aimed to directly defend its interests in the region. This was officially articulated in Theodore Roosevelt's Big Stick Doctrine, which modified the old Monroe Doctrine, which had simply aimed to deter European intervention in the hemisphere. At the conclusion of the Spanish–American War the new government of Cuba and the United States signed the Platt Amendment in 1902, which authorized the United States to intervene in Cuban affairs when the United States deemed necessary. In Colombia, United States sought the concession of a territory in Panama to build a much anticipated canal across the isthmus. The Colombian government opposed this, but a Panamanian insurrection provided the United States with an opportunity. The United States backed Panamanian independence and the new nation granted the concession. These were not the only interventions carried out in the region by the United States. In the first decades of the twentieth century, there were several military incursions into Central America and the Caribbean, mostly in defense of commercial interests, which became known as the "Banana Wars."

The greatest political upheaval in the second decade of the century took place in Mexico. In 1908, President Porfirio Díaz, who had been in office since 1884, promised that he would step down in 1910. Francisco I. Madero, a moderate liberal whose aim was to modernize the country while preventing a socialist revolution, launched an election campaign in 1910. Díaz, however, changed his mind and ran for office once more. Madero was arrested on election day and Díaz declared the winner. These events provoked uprisings, which became the start of the Mexican Revolution. Revolutionary movements were organized and some key leaders appeared: Pancho Villa in the north, Emiliano Zapata in the south, and Madero in Mexico City. Madero's forces defeated the federal army in early 1911, assumed temporary control of the government and won a second election later on November 6, 1911. Madero undertook moderate reforms to implement greater democracy in the political system but failed to satisfy many of the regional leaders in what had become a revolutionary situation. Madero's failure to address agrarian claims led Zapata to break with Madero and resume the revolution. On February 18, 1913 Victoriano Huerta, a conservative general organized a coup d'état with the support of the United States; Madero was killed four days later. Other revolutionary leaders such as Villa, Zapata, and Venustiano Carranza continued to militarily oppose the federal government, now under Huerta's control. Allies Zapata and Villa took Mexico City in March 1914, but found themselves outside of their elements in the capital and withdrew to their respective bastions. This allowed Carranza to assume control of the central government. He then organized the repression of the rebel armies of Villa and Zapata, led in particular by General Álvaro Obregón. The Mexican Constitution of 1917, still the current constitution, was proclaimed but initially little enforced. The efforts against the other revolutionary leaders continued. Zapata was assassinated on April 10, 1919. Carranza himself was assassinated on May 15, 1920, leaving Obregón in power, who was officially elected president later that year. Finally in 1923 Villa was also assassinated. With the removal of the main rivals Obregón is able to consolidate power and relative peace returned to Mexico. Under the Constitution a liberal government is implemented but some of the aspirations of the working and rural classes remained unfulfilled. (See also, Agrarian land reform in Mexico.)

The prestige of Germany and German culture in Latin America remained high after the war but did not recover to its pre-war levels.[18][19] Indeed, in Chile the war bought an end to a period of scientific and cultural influence writer Eduardo de la Barra scorningly called "the German bewichment" (Spanish: el embrujamiento alemán).[20]

Sports

Sports became increasingly popular, drawing enthusiastic fans to large stadia.[21] The International Olympic Committee (IOC) worked to encourage Olympic ideals and participation. Following the 1922 Latin American Games in Rio de Janeiro, the IOC helped to establish national Olympic committees and prepare for future competition. In Brazil, however, sporting and political rivalries slowed progress as opposing factions fought to control of international sport. The 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris and the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam saw greatly increased participation from Latin American athletes.[22] English and Scottish engineers brought futebol (soccer) to Brazil in the late 1800s. The International Committee of the YMCA of North America and the Playground Association of America played major roles in training coaches. .[23]

1930–1960

The Great Depression posed a great challenge to the region. The collapse of the world economy meant that the demand for raw materials drastically declined, undermining many of the economies of Latin America. Intellectuals and government leaders in Latin America turned their backs on the older economic policies and turned toward import substitution industrialization. The goal was to create self-sufficient economies, which would have their own industrial sectors and large middle classes and which would be immune to the ups and downs of the global economy. Despite the potential threats to United States commercial interests, the Roosevelt administration (1933–1945) understood that the United States could not wholly oppose import substitution. Roosevelt implemented a Good Neighbor policy and allowed the nationalization of some American companies in Latin America. Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas nationalized American oil companies, out of which he created Pemex. Cárdenas also oversaw the redistribution of a quantity of land, fulfilling the hopes of many since the start of the Mexican Revolution. The Platt Amendment was also repealed, freeing Cuba from legal and official interference of the United States in its politics. The Second World War also brought the United States and most Latin American nations together.[24]

In the postwar period, the expansion of communism became the greatest political issue for both the United States and governments in the region. The start of the Cold War forced governments to choose between the United States and the Soviet Union. Following the 1948 Costa Rica Civil War, the nation established a new constitution and was recognized as the first legitimate democracy in Latin America[25] However, the new Costa Rican government, which now was constitutionally required to ban the presence of a standing military, did not seek regional influence and was distracted further by conflicts with neighboring Nicaragua.

Several socialist and communist insurgencies broke out in Latin America throughout the entire twentieth century, but the most successful one was in Cuba. The Cuban Revolution was led by Fidel Castro against the regime of Fulgencio Batista, who since 1933 was the principal autocrat in Cuba. Since the 1860s the Cuban economy had focused on the cultivation of sugar, of which 82% was sold in the American market by the twentieth century. Despite the repeal of the Platt Amendment, the United States still had considerable influence in Cuba, both in politics and in everyday life. In fact Cuba had a reputation of being the "brothel of the United States," a place where Americans could find all sorts of licit and illicit pleasures, provided they had the cash. Despite having the socially advanced constitution of 1940, Cuba was plagued with corruption and the interruption of constitutional rule by autocrats like Batista. Batista began his final turn as the head of the government in a 1952 coup. The coalition that formed under the revolutionaries hoped to restore the constitution, reestablish a democratic state and free Cuba from the American influence. The revolutionaries succeeded in toppling Batista on January 1, 1959. Castro, who initially declared himself as a non-socialist, initiated a program of agrarian reforms and nationalizations in May 1959, which alienated the Eisenhower administration (1953–61) and resulted in the United States breaking of diplomatic relations, freezing Cuban assets in the United States and placing an embargo on the nation in 1960. The Kennedy administration (1961–1963) authorized the funding and support of an invasion of Cuba by exiles. The invasion failed and radicalized the revolutionary government's position. Cuba officially proclaimed itself socialist and openly became an ally of the Soviet Union. The military collaboration between Cuba and the Soviet Union, which included the placement of intercontinental ballistic missiles in Cuba precipitated the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962.

Late-20th-century military regimes and revolutions

By the 1970s, leftists had acquired a significant political influence which prompted the right-wing, ecclesiastical authorities and a large portion of each individual country's upper class to support coups d'état to avoid what they perceived as a communist threat. This was further fueled by Cuban and United States intervention which led to a political polarization. Most South American countries were in some periods ruled by military dictatorships that were supported by the United States of America.

Around the 1970s, the regimes of the Southern Cone collaborated in Operation Condor killing many leftist dissidents, including some urban guerrillas.[26]

Washington Consensus

The set of specific economic policy prescriptions that were considered the "standard" reform package were promoted for crisis-wracked developing countries by Washington, DC-based institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and the US Treasury Department during the 1980s and '90s.

In recent years, several Latin American countries led by socialist or other left wing governments—including Argentina and Venezuela—have campaigned for (and to some degree adopted) policies contrary to the Washington Consensus set of policies. (Other Latin counties with governments of the left, including Brazil, Chile and Peru, have in practice adopted the bulk of the policies). Also critical of the policies as actually promoted by the International Monetary Fund have been some US economists, such as Joseph Stiglitz and Dani Rodrik, who have challenged what are sometimes described as the "fundamentalist" policies of the International Monetary Fund and the US Treasury for what Stiglitz calls a "one size fits all" treatment of individual economies. The term has become associated with neoliberal policies in general and drawn into the broader debate over the expanding role of the free market, constraints upon the state, and US influence on other countries' national sovereignty.

21st century

Turn to the left

Since the 2000s, or 1990s in some countries, left-wing political parties have risen to power. Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff in Brazil, Fernando Lugo in Paraguay, Néstor and Cristina Kirchner in Argentina, Tabaré Vázquez and José Mujica in Uruguay, the Lagos and Bachelet governments in Chile, Evo Morales in Bolivia, Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua, Manuel Zelaya in Honduras (although deposed by the 28 June 2009 coup d'état), and Rafael Correa of Ecuador are all part of this wave of left-wing politicians, who also often declare themselves socialists, Latin Americanists or anti-imperialists.

Turn to the right and resurgence of the left

The conservative wave (Portuguese: onda conservadora) is a political phenomenon that emerged in mid-2010 in South America. In Brazil, it began roughly around the time Dilma Rousseff, in a tight election, won the 2014 presidential election, kicking off the fourth term of the Workers' Party in the highest position of government.[27] In addition, according to the political analyst of the Inter-Union Department of Parliamentary Advice, Antônio Augusto de Queiroz, the National Congress elected in 2014 may be considered the most conservative since the "re-democratization" movement, noting an increase in the number of parliamentarians linked to more conservative segments, as ruralists, military, police and religious.

The subsequent economic crisis of 2015 and investigations of corruption scandals led to a right-wing movement that sought to rescue ideas from economic liberalism and conservatism in opposition to left-wing policies.[28]

A resurgence of the rise of left-wing political parties in Latin America by their electoral victories, however, was initiated by Mexico in 2018 and Argentina in 2019, and further strengthened by Bolivia in 2020 along with Peru, Honduras and Chile in 2021 and Colombia and Brazil in 2022.[29]

See also

- Economic history of Latin America

- Environmental history of Latin America

- Historiography#Latin America

- Historiography of Colonial Spanish America

- Latin American economy

- Latin America–United Kingdom relations

- List of history journals#Latin America and the Caribbean

- Conference on Latin American History

- Latin American studies

Pre-Columbian

Colonization

British colonization of the Americas, Danish colonization of the Americas, Dutch colonization of the Americas, New Netherland, French New France, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, New Spain, Conquistador, Spanish conquest of Yucatán, Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, Spanish missions in California, Swedish

History by region

History by country

References

- Mignolo, Walter (2005). The Idea of Latin America. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 77–80. ISBN 978-1-4051-0086-1.

- McGuiness, Aims (2003). "Searching for 'Latin America': Race and Sovereignty in the Americas in the 1850s" in Appelbaum, Nancy P. et al. (eds.). Race and Nation in Modern Latin America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 87-107. ISBN 0-8078-5441-7

- Chasteen, John Charles (2001). Born in Blood and Fire: A Concise History of Latin America. W. W. Norton. p. 156. ISBN 0-393-97613-0.

- Butland, Gilbert J. (1960). Latin America: A Regional Geography. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 115–188. ISBN 0-470-12658-2. Dozer, Donald Marquand (1962). Latin America: An Interpretive History. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1–15. Szulc, Tad (1965). Latin America. New York Times Company. pp. 13–17. Olien, Michael D. (1973). Latin Americans: Contemporary Peoples and Their Cultural Traditions. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. pp. 1–5. ISBN 0-03-086251-5. Black, Jan Knippers, ed. (1984). Latin America: Its Problems and Its Promise: A Multidisciplinary Introduction. Boulder: Westview Press. pp. 362–378. ISBN 0-86531-213-3. Bruns, E. Bradford (1986). Latin America: A Concise Interpretive History (4 ed.). New York: Prentice-Hall. pp. 224–227. ISBN 0-13-524356-4. Skidmore, Thomas E.; Peter H. Smith (2005). Modern Latin America (6 ed.). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 351–355. ISBN 0-19-517013-X.

- Elsey, Brenda (2017). "Sport in Latin America". In Edelman, Robert (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Sports History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199858910.

- Sherburne F. Cook and Woodrow Borah, Essays in Population History 3 vols. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1971-1979.

- David P. Henige, Numbers from Nowhere: the American Indian Contact Population Debate, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1998.

- Nobel David Cook, Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492-1650. New York: Cambridge University Press 1998.

- Zinn, Howard (2015). A People's History of the United States. New York: HarperCollins. p. 6.

- "The Maya Codices". about.com.

- McKnight, Afro-Latino Voices p 52.

- McKnight, Afro-Latino Voices p. 61.

- McKnight, Afro-Latino Voices p. 64.

- McKnight, Afro-Latino Voices p. 176.

- McKnight, Afro-Latino Voices p. 175.

- McKnight, Afro-Latino Voices p. 193.

- Christopher Minster (2007). "The Federal Republic of Central America (1823-1840)". About.com. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- Sanhueza, Carlos (2011). "El debate sobre "el embrujamiento alemán" y el papel de la ciencia alemana hacia fines del siglo XIX en Chile" (PDF). Ideas viajeras y sus objetos. El intercambio científico entre Alemania y América austral. Madrid–Frankfurt am Main: Iberoamericana–Vervuert (in Spanish). pp. 29–40.

- Penny, H. Glenn (2017). "Material Connections: German Schools, Things, and Soft Power in Argentina and Chile from the 1880s through the Interwar Period". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 59 (3): 519–549. doi:10.1017/S0010417517000159. S2CID 149372568. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- Sanhueza, Carlos (2011). "El debate sobre "el embrujamiento alemán" y el papel de la ciencia alemana hacia fines del siglo XIX en Chile" (PDF). Ideas viajeras y sus objetos. El intercambio científico entre Alemania y América austral. Madrid–Frankfurt am Main: Iberoamericana–Vervuert (in Spanish). pp. 29–40.

- David M.K. Sheinin, ed., Sports Culture in Latin American History (2015).

- Cesar R. Torres, "The Latin American 'Olympic Explosion’ of the 1920s: causes and consequences." International Journal of the History of Sport 23.7 (2006): 1088-1111.

- Claudia Guedes, "‘Changing the cultural landscape’: English engineers, American missionaries, and the YMCA bring sports to Brazil–the 1870s to the 1930s." International Journal of the History of Sport 28.17 (2011): 2594-2608.

- Victor Bulmer-Thomas, The Economic History of Latin America since Independence (2nd ed. 2003) pp 189-231.

- Mainwaring, Scott; Pérez-Liñán, Aníbal (December 2008). "Regime legacies and democratization: explaining variance in the level of democracy in Latin America, 1978-2004" (PDF). Kellogg Institute.

- Victor Flores Olea. "Editoriales – El Universal – 10 de abril 2006 : Operacion Condor" (in Spanish). El Universal (Mexico). Archived from the original on 2007-06-28. Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- Boulos, Guilherme. "Onda Conservadora". Retrieved 11 October 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Is there a right-wing surge in South America? | DW | 28.10.2018". DW.COM.

- Taher, Rahib (9 January 2021). "A Miraculous MAS Victory in Bolivia and the Resurgence of the Pink Tide". The Science Survey. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

Further reading

- Adam, Thomas, ed. Germany and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History (3 vol, 2005) excerpt

- Bakewell, Peter, A History of Latin America" (Blackwell History of the World (Blackwell, 1997)

- Bethell, Leslie (ed.), The Cambridge History of Latin America, Cambridge University Press, 12 vol, 1984–2008

- Burns, E. Bradford, Latin America: A Concise Interpretive History, paperback, Prentice Hall 2001, 7th edition

- Goebel, Michael, "Globalizatitionalism in Latin America, c.1750-1950", New Global Studies 3 (2009).

- Halperín Donghi, Tulio. The contemporary history of Latin America. Durham : Duke University Press, 1993.

- Herring, Hubert, A History of Latin America: from the Beginnings to the Present, 1955. ISBN 0-07-553562-9

- Kaufman, Will, and Heidi Slettedahl Macpherson, eds. Britain and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History (3 vol 2005), 1157pp; encyclopedic coverage; excerpt

- Lockhart, James and Stuart B. Schwartz. Early Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1983.

- Marshall , Bill, ed. France and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History (3 vol. 2005) excerpt

- Mignolo, Walter. The Idea of Latin America. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell 2005. ISBN 978-1-4051-0086-1.

- Miller, Rory. Britain and Latin America in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. London: Longman 1993.

- Miller, Shawn William. An Environmental History of Latin America. New York: Cambridge University Press 2007.

- Schwaller, John Frederick. The History of the Catholic Church in Latin America: From Conquest to Revolution and Beyond (New York University Press; 2011) 319 pages

- Trigger, Bruce, and Wilcomb E. Washburn, eds. The Cambridge history of the native peoples of the Americas (3 vols. 1996)

- Keen, Benjamin; Haynes, Keith (2013). A History of Latin America (9th ed.). Boston: Wadsworth.

Historiography

- Murillo, Dana Velasco. "Modern local history in Spanish American historiography." History Compass 15.7 (2017). DOI: 10.1111/hic3.12387

Colonial era

- Adelman, Jeremy, ed. Colonial Legacies: The Problem of Persistence in Latin American History. New York: Routledge 1999.

- Alchon, Suzanne Austin. A Pest in the Land: New World Epidemics in Global Perspective. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2003.

- Andrien, Kenneth J. The Human Tradition in Colonial Spanish America. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources 2002.

- Brading, D.A. The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, 1492-1867. New York: Cambridge University Press 1991.

- Cañizares-Esguerra, Jorge. How to Write the History of the New World: Histories, Epistemologies, and Identities in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2001.

- Brown, Jonathan C. Latin America: A Social History of the Colonial Period, Wadsworth Publishing Company, 2nd edition 2004.

- Crosby, Alfred W. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. 30th anniversary edition. Westport: Praeger 2003.

- Denevan, William M., ed. The Native Population of the Americas ca. 1492. 2nd edition. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press 1992.

- Donahue-Wallace, Kelly. Art and Architecture of Viceregal Latin America, 1521-1821. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2008.

- Fisher, John R. Economic Aspects of Spanish Imperialism in America, 1492-1810. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press 1997.

- Gonzalez, Ondina E. and Bianca Premo, eds. Raising an Empire: Children in Early Modern Iberia and Colonial Latin America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2007.

- Haring, Clarence H., The Spanish Empire in America. New York: Oxford University Press 1947.

- Hill, Ruth. Hierarchy, Commerce, and Fraud in Bourbon Spanish America. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press 2006.

- Hoberman, Louisa Schell and Susan Migden Socolow, eds. Cities and Society in Colonial Spanish America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1986.

- Hoberman, Louisa Schell and Susan Migden Socolow, eds. The Countryside in Colonial Spanish America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1986.

- Johnson, Lyman L. and Sonya Lipsett-Rivera, eds. The Faces of Honor: Sex, Shame, and Violence in Colonial Latin America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1998.

- Kagan, Richard. Urban Images of the Hispanic World, 1493-1793. New Haven: Yale University Press 2000.

- Kinsbruner, Jay. The Colonial Spanish-American City: Urban Life in the Age of Atlantic Capitalism. Austin: University of Texas Press 2005.

- Klein, Herbert S., The American Finances of the Spanish Empire: Royal Income and Expenditures in Colonial Mexico, Peru, and Bolivia, 1680-1809. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1998.

- Klein, Herbert S. and Ben Vinson III. African Slavery in Latin America and the Caribbean. 2nd edition. New York: Oxford University Press 2007.

- Landers, Jane G. and Barry M. Robinson, eds. Slaves, Subjects, and Subversives: Blacks in Colonial Latin America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2006.

- Lane, Kris, Pillaging the Empire: Piracy in the Americas, 1500-1750. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe 1998.

- Lanning, John Tate. The Royal Protomedicato: The Regulation of the Medical Profession in the Spanish Empire. Ed. John Jay TePaske. Durham: Duke University Press 1985.

- Lockhart, James and Schwartz, Stuart B., Early Latin America. New York: Cambridge University Press 1983.

- Lynch, John. The Hispanic World in Crisis and Change, 1598-1700. Oxford: Basil Blackwell 1992.

- MacLeod, Murdo J., Spanish Central America: A Socioeconomic History, 1520-1720. Revised edition. Austin: University of Texas Press 2007.

- McKnight, Kathryn J. Afro-Latino Voices: Narratives from the Early Modern Ibero-Atlantic World, 1550–1812 (Hackett Publishing Company 2009)

- Muldoon, James. The Americas in the Spanish World Order: The Justification of Conquest in the Seventeenth Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press 1998.

- Myers, Kathleen Ann. Neither Saints nor Sinners: Writing the Lives of Women in Spanish America. New York: Oxford University Press 2003.

- Pagden, Anthony. Spanish Imperialism and the Political Imagination: Studies in European and Spanish-American Social and Political Theory, 1513-1830. New Haven: Yale University Press 1990.

- Paquette, Gabriel B. Enlightenment, Governance, and Reform in Spain and its Empire, 1759-1808. New York: Palgrave Macmillan 2008.

- Pearce, Adrian. British Trade with Spanish America, 1763-1808. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press 2008.

- Perry, Elizabeth Mary and Anne J. Cruz, eds. Cultural Encounters: The Impact of the Inquisition in Spain and the New World. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1991.

- Powers, Karen Vieira. Women in the Crucible of Conquest: The Gendered Genesis of Spanish American Society, 1500-1600. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2005.

- Robinson, David J., ed. Migration in Colonial Spanish America. New York: Cambridge University Press 1990.

- Russell-Wood, A.J.R. Slavery and Freedom in Colonial Brazil. 2nd. ed. Oneworld Publications 2002.

- Safier, Neil. Measuring the New World: Enlightenment Science and South America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2008.

- Schwartz, Stuart B. All Can be Saved: Religious Tolerance and Salvation in the Atlantic World. New Haven: Yale University Press 1981.

- Socolow, Susan Migden. The Women of Colonial Latin America. New York: Cambridge University Press 2000.

- Stein, Stanley J. and Barbara H. Stein. Apogee of Empire: Spain and New Spain in the Age of Charles III, 1759-1789. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press 2003.

- Stein, Stanley J. and Barbara H. Stein. Silver, Trade, and War: Spain and America in the Making of Early Modern Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press 2000.

- Super, John D. Food, Conquest, and Colonization in Sixteenth-Century Spanish America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1988.

- Trusted, Marjorie. The Arts of Spain: Iberia and Latin America 1450-1700. University Park: Penn State Press 2007.

- Twinam, Ann. Public Lives, Private Secrets: Gender, Honor, Sexuality, and Illegitimacy in Colonial Spanish America. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1999.

- Van Oss, A.C. Church and Society in Spanish America. Amsterdam: Aksant 2003.

- Weber, David J. Bárbaros: Spaniards and Their Savages in the Age of Enlightenment. New Haven: Yale University Press 2005.

Independence era

- Adelman, Jeremy. Sovereignty and Revolution in the Iberian Atlantic. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2006.

- Andrien, Kenneth J. and Lyman L. Johnson, eds. The Political Economy of Spanish America in the Age of Revolution, 1750-1850. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1994.

- Blanchard, Peter. Under the Flags of Freedom: Slave Soldiers and the Wars of Independence in Spanish America. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press 2008.

- Chasteen, John Charles. Americanos: Latin America's Struggle for Independence. New York: Oxford University Press 2008.

- Davies, Catherine, Claire Brewster, and Hilary Owen. South American Independence: Gender, Politics, Text. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press 2007.

- Halperín Donghi, Tulio. The aftermath of revolution in Latin America. New York, Harper & Row [1973]

- Johnson, Lyman L. and Enrique Tandanter, eds. Essays on the Price History of Eighteenth-Century Latin America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1990.

- Lynch, John, ed. Latin American revolutions, 1808-1826: old and new world origins (University of Oklahoma Press, 1994)

- Lynch, John. The Spanish American Revolutions, 1808-1826 (1973)

- McFarlane, Anthony. War and Independence in Spanish America (2008).

- Racine, Karen. "Simón Bolívar and friends: Recent biographies of independence figures in Colombia and Venezuela" History Compass 18#3 (Feb 2020) https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12608

- Rodríguez, Jaime E. Independence of Spanish America (Cambridge University Press, 1998)

Modern era

- Barclay, Glen. Struggle for a Continent: The Diplomatic History of South America, 1917-1945 (1972) 214pp

- Bulmer-Thomas, Victor. The Economic History of Latin America since Independence (2nd ed. Cambridge UP, 2003) online

- Burns, E. Bradford, The Poverty of Progress: Latin America in the Nineteenth Century. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1980.

- Drinot, Paulo and Alan Knight, eds. The Great Depression in Latin America (2014) excerpt

- Gilderhus, Mark T. The Second Century: US--Latin American Relations Since 1889 (Rowman & Littlefield, 2000)

- Green, Duncan, Silent Revolution: The Rise and Crisis of Market Economics in Latin America, New York University Press 2003

- Kirkendall, Andrew J. "Cold War Latin America: The State of the Field" H-Diplo Essay No. 119: An H-Diplo State of the Field Essay (Nov. 2014) online evaluates 50+ scholarly books and articles

- Pettinà, Vanni. A Compact History of Latin America’s Cold War (University of North Carolina Press, 2022) See reviews by 5 scholars and reply by Pettina online

- Schoultz, Lars, Beneath the United States: A History of U.S. Policy Toward Latin America, Harvard University Press 1998

- Skidmore, Thomas E. and Smith, Peter H., Modern Latin America, Oxford University Press 2005

- Stein, Stanley J. and Shane J. Hunt. "Principal Currents in the Economic Historiography of Latin America," Journal of Economic History Vol. 31, No. 1, (March 1971), pp. 222–253 in JSTOR

- Valenzuela, Arturo. "Latin American Presidencies Interrupted" in Journal of Democracy Volume 15, Number 4 October 2004

- Woodward, Ralph Lee, Positivism in Latin America, 1850-1900: Are order and progress reconcilable? Lexington, Mass., Heath [1971]

.svg.png.webp)