Laurasia

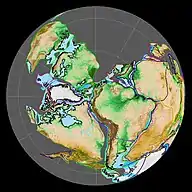

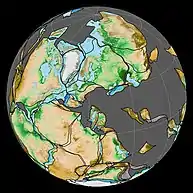

Laurasia (/lɔːˈreɪʒə, -ʃiə/)[1] was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around 335 to 175 million years ago (Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana 215 to 175 Mya (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pangaea, drifting farther north after the split and finally broke apart with the opening of the North Atlantic Ocean c. 56 Mya. The name is a portmanteau of Laurentia and Asia.[2]

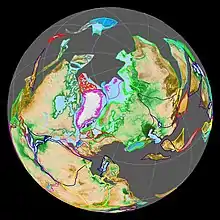

Laurasia (centre) and Gondwana (bottom) as part of Pangaea 200 Mya (Early Jurassic) | |

| Historical continent | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1,071 Mya (Proto-Laurasia) 253 Mya |

| Type | Supercontinent |

| Today part of |

|

| Smaller continents | |

| Tectonic plates | |

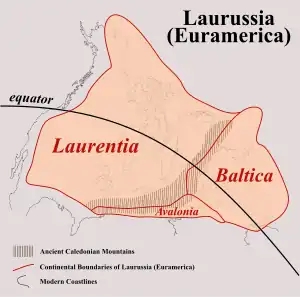

Laurentia, Avalonia, Baltica, and a series of smaller terranes, collided in the Caledonian orogeny c. 400 Ma to form Laurussia/Euramerica. Laurussia/Euramerica then collided with Gondwana to form Pangaea. Kazakhstania and Siberia were then added to Pangaea 290–300 Ma to form Laurasia. Laurasia finally became an independent continental mass when Pangaea broke up into Gondwana and Laurasia.[3]

Terminology and origin of the concept

Laurentia, the Palaeozoic core of North America and continental fragments that now make up part of Europe, collided with Baltica and Avalonia in the Caledonian orogeny c. 430–420 Mya to form Laurussia. In the Late Carboniferous Laurussia and Gondwana formed Pangaea. Siberia and Kazakhstania finally collided with Baltica in the Late Permian to form Laurasia.[4] A series of continental blocks that now form East and Southeast Asia were later added to Laurasia.

In 1904–1909 Austrian geologist Eduard Suess proposed that the continents in the Southern Hemisphere were once merged into a larger continent called Gondwana. In 1915 German meteorologist Alfred Wegener proposed the existence of a supercontinent called Pangaea. In 1937 South African geologist Alexander du Toit proposed that Pangaea was divided into two larger landmasses, Laurasia in the Northern Hemisphere and Gondwana in the Southern Hemisphere, separated by the Tethys Ocean.[5]

"Laurussia" was defined by Swiss geologist Peter Ziegler in 1988 as the merger between Laurentia and Baltica along the northern Caledonian suture. The "Old Red Continent" is an informal name often used for the Silurian-Carboniferous deposits in the central landmass of Laurussia.[6]

Several earlier supercontinents proposed and debated in the 1990s and later (e.g. Rodinia, Nuna, Nena) included earlier connections between Laurentia, Baltica, and Siberia.[5] These original connections apparently survived through one and possibly even two Wilson Cycles, though their intermittent duration and recurrent fit is debated.[7]

Proto-Laurasia

Pre–Rodinia

Laurentia and Baltica first formed a continental mass known as Proto-Laurasia as part of the supercontinent Columbia which was assembled 2,100—1,800 Mya to encompass virtually all known Archaean continental blocks.[8] Surviving sutures from this assembly are the Trans-Hudson orogen in Laurentia; Nagssugtoqidian orogen in Greenland; the Kola-Karelian (the northwest margin of the Svecokarelian/Svecofennian orogen) and the Volhyn—Central Russia and Pachelma orogenies (across western Russia) in Baltica; and the Akitkan Orogen in Siberia.[9]

Additional Proterozoic crust was accreted 1,800—1,300 Mya, especially along the Laurentia—Greenland—Baltica margin.[8] Laurentia and Baltica formed a coherent continental mass with southern Greenland and Labrador adjacent to the Arctic margin of Baltica. A magmatic arc extended from Laurentia through southern Greenland to northern Baltica.[10] The breakup of Columbia began 1,600 Mya, including along the western margin of Laurentia and northern margin of Baltica (modern coordinates), and was completed c. 1,300—1,200 Mya, a period during which mafic dike swarms were emplaced, including MacKenzie and Sudbury in Laurentia.[8]

Traces left by large igneous provinces provide evidences for continental mergers during this period. Those related to Proto-Laurasia includes:[11]

- 1,750 Mya extensive magmatism in Baltica, Sarmatia (Ukraine), southern Siberia, northern Laurentia, and West Africa indicate these cratons were linked to each other;

- a 1,630–1,640 Mya-old continent composed of Siberia, Laurentia, and Baltica is suggested by sills in southern Siberia that can be connected to the Melville Bugt dyke swarm in western Greenland; and

- a major large igneous province 1,380 Mya during the breakup of the Nuna/Columbia supercontinent connects Laurentia, Baltica, Siberia, Congo, and West Africa.

Rodinia

View centred on 30°S,130°E.

In the vast majority of plate tectonic reconstructions, Laurentia formed the core of the supercontinent Rodinia, but the exact fit of various continents within Rodinia is debated. In some reconstructions, Baltica was attached to Greenland along its Scandinavian or Caledonide margin while Amazonia was docked along Baltica's Tornquist margin. Australia and East Antarctica were located on Laurentia's western margin.[13]

Siberia was located near but at some distance from Laurentia's northern margin in most reconstructions.[14] In the reconstruction of some Russian geologists, however, the southern margin (modern coordinates) of Siberia merged with the northern margin of Laurentia, and these two continents broke up along what is now the 3,000 km (1,900 mi)-long Central Asian Foldbelt no later than 570 Mya and traces of this breakup can still be found in the Franklin dike swarm in northern Canada and the Aldan Shield in Siberia.[15]

The Proto-Pacific opened and Rodinia began to breakup during the Neoproterozoic (c. 750–600 Mya) as Australia-Antarctica (East Gondwana) rifted from the western margin of Laurentia, while the rest of Rodinia (West Gondwana and Laurasia) rotated clockwise and drifted south. Earth subsequently underwent a series of glaciations – the Varanger (c. 650 Mya, also known as Snowball Earth) and the Rapitan and Ice Brook glaciations (c. 610-590 Mya) – both Laurentia and Baltica were located south of 30°S, with the South Pole located in eastern Baltica, and glacial deposits from this period have been found in Laurentia and Baltica but not in Siberia.[16]

A mantle plume (the Central Iapetus Magmatic Province) forced Laurentia and Baltica to separate ca. 650–600 Mya and the Iapetus Ocean opened between them. Laurentia then began to move quickly (20 cm/year (7.9 in/year)) north towards the Equator where it got stuck over a cold spot in the Proto-pacific. Baltica remained near Gondwana in southern latitudes into the Ordovician.[16]

Pannotia

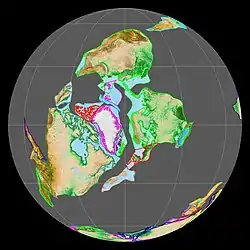

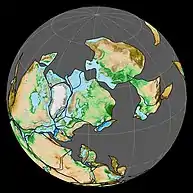

Right: Laurasia during the breakup of Pannotia at 550 Mya.

View centred on the South Pole.

Laurentia, Baltica, and Siberia remained connected to each other within the short-lived, Precambrian-Cambrian supercontinent Pannotia or Greater Gondwana. At this time a series of continental blocks – Peri-Gondwana – that now form part of Asia, the Cathaysian terranes – Indochina, North China, and South China – and Cimmerian terranes – Sibumasu, Qiangtang, Lhasa, Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkey – were still attached to the Indian–Australian margin of Gondwana. Other blocks that now form part of southwestern Europe and North America from New England to Florida were still attached to the African-South American margin of Gondwana.[17] This northward drift of terranes across the Tethys also included the Hunic terranes, now spread from Europe to China.[18]

Pannotia broke apart in the late Precambrian into Laurentia, Baltica, Siberia, and Gondwana. A series of continental blocks – the Cadomian–Avalonian, Cathaysian, and Cimmerian terranes – broke away from Gondwana and began to drift north.[19]

Euramerica/Laurussia

Laurentia remained almost static near the Equator throughout the early Palaeozoic, separated from Baltica by the up to 3,000 km (1,900 mi)-wide Iapetus Ocean.[20] In the Late Cambrian, the mid-ocean ridge in the Iapetus Ocean subducted beneath Gondwana which resulted in the opening of a series of large back-arc basins. During the Ordovician, these basins evolved into a new ocean, the Rheic Ocean, which separated a series of terranes – Avalonia, Carolinia, and Armorica – from Gondwana.[21]

Avalonia rifted from Gondwana in the Early Ordovician and collided with Baltica near the Ordovician–Silurian boundary (480–420 Mya). Baltica-Avalonia was then rotated and pushed north towards Laurentia. The collision between these continents closed the Iapetus Ocean and formed Laurussia, also known as Euramerica. Another historical term for this continent is the Old Red Continent or Old Red Sandstone Continent, in reference to abundant red beds of the Old Red Sandstone during the Devonian. The continent covered 37,000,000 km2 (14,000,000 sq mi) including several large Arctic continental blocks.[20][21]

With the Caledonian orogeny completed Laurussia was delimited thus:[22]

- The eastern margin were the Barents Shelf and Moscow Platform;

- the western margin were the western shelves of Laurentia, later affected by the Antler orogeny;

- the northern margin was the Innuitian-Lomonosov orogeny which marked the collision between Laurussia and the Arctic Craton;

- and the southern margin was a Pacific-style active margin where the northward directed subduction of the ocean floor between Gondwana and Laurussia pushed continental fragments towards the latter.

During the Devonian (416-359 Mya) the combined landmass of Baltica and Avalonia rotated around Laurentia, which remained static near the Equator. The Laurentian warm, shallow seas and on shelves a diverse assemblage of benthos evolved, including the largest trilobites exceeding 1 m (3 ft 3 in). The Old Red Sandstone Continent stretched across northern Laurentia and into Avalonia and Baltica but for most of the Devonian a narrow seaway formed a barrier where the North Atlantic would later open. Tetrapods evolved from fish in the Late Devonian, with the oldest known fossils from Greenland. Low sea-levels during the Early Devonian produced natural barriers in Laurussia which resulted in provincialism within the benthic fauna. In Laurentia the Transcontinental Arch divided brachiopods into two provinces, with one of them confined to a large embayment west of the Appalachians. By the Middle Devonian, these two provinces had been united into one and the closure of the Rheic Ocean finally united faunas across Laurussia. High plankton productivity from the Devonian-Carboniferous boundary resulted in anoxic events that left black shales in the basins of Laurentia.[23]

Pangaea

The subduction of the Iapetus Ocean resulted in the first contact between Laurussia and Gondwana in the Late Devonian and terminated in full collision or the Hercynian/Variscan orogeny in the early Carboniferous (340 Mya).[22] The Variscan orogeny closed the Rheic Ocean (between Avalonia and Armorica) and the Proto-Tethys Ocean (between Armorica and Gondwana) to form the supercontinent Pangaea.[24] The Variscan orogeny is complex and the exact timing and the order of the collisions between involved microcontinents has been debated for decades.[25]

Pangaea was completely assembled by the Permian except for the Asian blocks. The supercontinent was centred on the Equator during the Triassic and Jurassic, a period that saw the emergence of the Pangaean megamonsoon.[26] Heavy rainfall resulted in high groundwater tables, in turn resulting in peat formation and extensive coal deposits.[27]

During the Cambrian and Early Ordovician, when wide oceans separated all major continents, only pelagic marine organisms, such as plankton, could move freely across the open ocean and therefore the oceanic gaps between continents are easily detected in the fossil records of marine bottom dwellers and non-marine species. By the Late Ordovician, when continents were pushed closer together closing the oceanic gaps, benthos (brachiopods and trilobites) could spread between continents while ostracods and fishes remained isolated. As Laurussia formed during the Devonian and Pangaea formed, fish species in both Laurussia and Gondwana began to migrate between continents and before the end of the Devonian similar species were found on both sides of what remained of the Variscan barrier.[28]

The oldest tree fossils are from the Middle Devonian pteridophyte Gilboa forest in central Laurussia (today New York, United States).[29] In the late Carboniferous, Laurussia was centred on the Equator and covered by tropical rainforests, commonly referred to as the coal forest. By the Permian, the climate had become arid and these rainforests collapsed, lycopsids (giant mosses) were replaced by treeferns. In the dry climate a detritivorous fauna – including ringed worms, molluscs, and some arthropods – evolved and diversified, alongside other arthropods who were herbivorous and carnivorous, and tetrapods – insectivores and piscivores such as amphibians and early amniotes.[30]

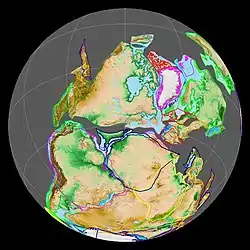

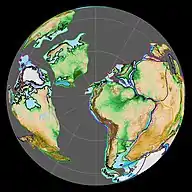

Laurasia

View centred on 25°N,35°E.

During the Carboniferous–Permian Siberia, Kazakhstan, and Baltica collided in the Uralian orogeny to form Laurasia.[31]

The Palaezoic-Mesozoic transition was marked by the reorganisation of Earth's tectonic plates which resulted in the assembly of Pangaea, and eventually its break-up. Caused by the detachment of subducted mantle slabs, this reorganisation resulted in rising mantle plumes that produced large igneous provinces when they reached the crust. This tectonic activity also resulted in the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Tentional stresses across Eurasia developed into a large system of rift basins (Urengoy, East Uralian-Turgay and Khudosey) and flood basalts in the West Siberian Basin, the Pechora Basin, and South China.[32]

Laurasia and Gondwana were equal in size but had distinct geological histories. Gondwana was assembled before the formation of Pangaea, but the assembly of Laurasia occurred during and after the formation of the supercontinent. These differences resulted in different patterns of basin formation and transport of sediments. East Antarctica was the highest ground within Pangaea and produced sediments that were transported across eastern Gondwana but never reached Laurasia. During the Palaeozoic, c. 30–40% of Laurasia but only 10–20% of Gondwana was covered by shallow marine water.[33]

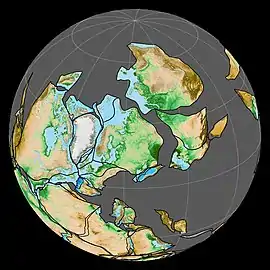

Asian blocks

View centred on 0°S,105°E.

During the assembly of Pangaea Laurasia grew as continental blocks broke off Gondwana's northern margin; pulled by old closing oceans in front of them and pushed by new opening oceans behind them.[34] During the Neoproterozoic-Early Paleozoic break-up of Rodinia the opening of the Proto-Tethys Ocean split the Asian blocks – Tarim, Qaidam, Alex, North China, and South China – from the northern shores of Gondwana (north of Australia in modern coordinates) and the closure of the same ocean reassembled them along the same shores 500–460 Mya resulting in Gondwana at its largest extent.[21]

The break-up of Rodinia also resulted in the opening of the long-lived Paleo-Asian Ocean between Baltica and Siberia in the north and Tarim and North China in the south. The closure of this ocean is preserved in the Central Asian Orogenic Belt, the largest orogen on Earth.[35]

North China, South China, Indochina, and Tarim broke off Gondwana during the Silurian-Devonian; Palaeo-Tethys opened behind them. Sibumasu and Qiantang and other Cimmerian continental fragments broke off in the Early Permian. Lhasa, West Burma, Sikuleh, southwest Sumatra, West Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo broke off during the Late Triassic-Late Jurassic.[36]

During the Carboniferous and Permian, Baltica first collided with Kazakhstania and Siberia, then North China with Mongolia and Siberia. By the middle Carboniferous, however, South China had already been in contact with North China long enough to allow floral exchange between the two continents. The Cimmerian blocks rifted from Gondwana in the Late Carboniferous.[31]

In the early Permian, the Neo-Tethys Ocean opened behind the Cimmerian terranes (Sibumasu, Qiantang, Lhasa) and, in the late Carboniferous, the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean closed in front. The eastern branch of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean, however, remained opened while Siberia was added to Laurussia and Gondwana collided with Laurasia.[34]

When the eastern Palaeo-Tethys closed 250–230 Mya, a series of Asian blocks – Sibumasu, Indochina, South China, Qiantang, and Lhasa – formed a separate southern Asian continent. This continent collided 240–220 Mya with a northern continent – North China, Qinling, Qilian, Qaidam, Alex, and Tarim – along the Central China orogen to form a combined East Asian continent. The northern margins of the northern continent collided with Baltica and Siberia 310–250 Ma, and thus the formation of the East Asian continent marked Pangaea at its greatest extent.[34] By this time, the rifting of western Pangaea had already begun.[31]

Flora and fauna

Pangaea split in two as the Tethys Seaway opened between Gondwana and Laurasia in the Late Jurassic. The fossil record, however, suggests the intermittent presence of a Trans-Tethys land bridge, though the location and duration of such a land bridge remains enigmatic.[37]

Pine trees evolved in the early Mesozoic c. 250 Mya and the pine genus originated in Laurasia in the Early Cretaceous c. 130 Mya in competition with faster growing flowering plants. Pines adapted to cold and arid climates in environments where the growing season was shorter or wildfire common; this evolution limited pine range to between 31° and 50° north and resulted in a split into two subgenera: Strobus adapted to stressful environments and Pinus to fire-prone landscapes. By the end of the Cretaceous pines were established across Laurasia, from North America to East Asia.[38]

From the Triassic to the Early Jurassic, before the break-up of Pangaea, archosaurs (crurotarsans, pterosaurs and dinosaurs including birds) had a global distribution, especially crurotarsans, the group ancestral to the crocodilians. This cosmopolitanism ended as Gondwana fragmented and Laurasia was assembled. Pterosaur diversity reach a maximum in the Late Jurassic—Early Cretaceous and plate tectonic didn't affect the distribution of these flying reptiles. Crocodilian ancestors also diversified during the Early Cretaceous but were divided into Laurasian and Gondwanan populations; true crocodilians evolved from the former. The distribution of the three major groups of dinosaurs – the sauropods, theropods, and ornithischians – was similar that of the crocodilians. East Asia remained isolated with endemic species including psittacosaurs (horned dinosaurs) and Ankylosauridae (club-tailed, armoured dinosaurs).[39]

Meanwhile, mammals slowly settled in Laurasia from Gondwana in the Triassic, the latter of which was the living area of their Permian ancestors. They split in two groups, with one returning to Gondwana (and stayed there after Pangaea split) while the other staying in Laurasia (until further descendants switched to Gondwana starting from the Jurassic).

In the early Eocene a peak in global warming led to a pan-Arctic fauna with alligators and amphibians present north of the Arctic Circle. In the early Palaeogene, landbridges still connected continents, allowing land animals to migrate between them. On the other hand, submerged areas occasionally divided continents: the Turgai Sea separated Europe and Asia from the Middle Jurassic to the Oligocene and as this sea or strait dried out, a massive faunal interchange took place and the resulting extinction event in Europe is known as the Grande Coupure.[40]

The Coraciiformes (an order of birds including kingfishers) evolved in Laurasia. While this group now has a mostly tropical distribution, they originated in the Arctic in the late Eocene c. 35 Mya from where they diversified across Laurasia and farther south across the Equator.[41]

The placental mammal group of Laurasiatheria is named after Laurasia.

Final split

In the Triassic–Early Jurassic (c. 200 Mya), the opening of the Central Atlantic Ocean was preceded by the formation of a series of large rift basins, such as the Newark Basin, between eastern North America, from what is today the Gulf of Mexico to Nova Scotia, and in Africa and Europe, from Morocco to Greenland.[42]

By c. 83 Mya spreading had begun in the North Atlantic between the Rockall Plateau, a continental fragment sitting on top of the Eurasian Plate, and North America. By 56 Mya Greenland had become an independent plate, separated from North America by the Labrador Sea-Baffin Bay Rift. By 33 Mya spreading had ceased in the Labrador Sea and relocated to the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.[43] The opening of the North Atlantic Ocean had effectively broken Laurasia in two.

References

Notes

- Oxford English Dictionary

- Du Toit 1937, p. 40

- Torsvik & Cocks 2004, Laurussia and Laurasia, pp. 558, 560

- Torsvik et al. 2012, From Laurentia to Laurussia and Laurasia: Overview, p. 6

- Meert 2012, pp. 991–992

- Ziegler 1988, Abstract

- Bleeker 2003, p. 108

- Zhao et al. 2004, Abstract

- Zhao et al. 2004, Summary and Discussion, pp. 114–115

- Zhao et al. 2002, Laurentia (North America and Greenland) and Baltica, pp. 145-149

- Ernst et al. 2013, Progress on continental reconstructions, pp. 8–9

- "Consensus" reconstruction from Li et al. 2008.

- Torsvik et al. 1996, Rodinia, pp. 236–237

- Li et al. 2008, Siberia–Laurentia connection, p. 189

- Yarmolyuk et al. 2006, p. 1031; Fig. 1, p. 1032

- Torsvik et al. 1996, Abstract; Initial break-up of Rodinia and Vendian glaciations, pp. 237–240

- Scotese 2009, p. 71

- Stampfli 2000, Palaeotethys, p. 3

- Scotese 2009, The break-up of Pannotia, p. 78

- Torsvik et al. 2012, p. 16

- Zhao et al. 2018, Closure of Proto-Tethys Ocean and the first assembly of East Asian blocks at the northern margin of Gondwana, pp. 7-10

- Ziegler 2012, Introduction, pp. 1–4

- Cocks & Torsvik 2011, Facies and faunas, pp. 10–11

- Rey, Burg & Casey 1997, Introduction, pp. 1–2

- Eckelmann et al. 2014, Introduction, pp. 1484–1486

- Parrish 1993, Paleogeographic Evolution of Pangea, p. 216

- Parrish 1993, Geological Evidence of the Pangean Megamonsoon, p. 223

- McKerrow et al. 2000, The narrowing oceans, pp. 10–11

- Lu et al. 2019, pp. 1–2

- Sahney, Benton & Falcon-Lang 2010, Introduction, p. 1079

- Blakey 2003, Assembly of Western Pangaea: Carboniferous–Permian, pp. 453–454; Assembly of Eastern Pangaea: Late Permian–Jurassic, p. 454; Fig. 10, p. 454

- Nikishin et al. 2002, Introduction, pp. 4–5; Fig. 4, p. 8

- Rogers & Santosh 2004, Differences Between Gondwana and Laurasia in Pangea, pp. 127, 130

- Zhao et al. 2018, Closure of Paleo-Tethys Ocean and assembly of Pangea with East Asian blocks, pp. 14-16

- Zhao et al. 2018, Closure of Paleo-Asian Ocean: collision of Tarim, Alex and North China with East Europe and Siberia, pp. 11-14

- Metcalfe 1999, pp. 15–16

- Gheerbrant & Rage 2006, Introduction, p. 225

- Keeley 2012, Introduction, pp. 445–446; Mesozoic origin and diversification, pp. 450–451

- Milner, Milner & Evans 2000, p. 319

- Milner, Milner & Evans 2000, p. 328

- McCullough et al. 2019, Conclusion, p. 7

- Olsen 1997, Introduction, p. 338

- Seton et al. 2012, Rockall–North America/Greenland, p. 222

Sources

- Blakey, R. C. (2003). Wong, T. E. (ed.). "Carboniferous–Permian paleogeography of the assembly of Pangaea". Proceedings of the XVTH International Congress on Carboniferous and Permian Stratigraphy. Utrecht. 10: 443–456.

- Bleeker, W. (2003). "The late Archean record: a puzzle in ca. 35 pieces" (PDF). Lithos. 71 (2–4): 99–134. Bibcode:2003Litho..71...99B. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2003.07.003. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- Cocks, L. R. M.; Torsvik, T. H. (2011). "The Palaeozoic geography of Laurentia and western Laurussia: a stable craton with mobile margins". Earth-Science Reviews. 106 (1–2): 1–51. Bibcode:2011ESRv..106....1C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.663.2972. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2011.01.007.

- Du Toit, A. L. (1937). Our wandering continents : an hypothesis of continental drifting. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. ISBN 9780598627582.

- Eckelmann, K.; Nesbor, H. D.; Königshof, P.; Linnemann, U.; Hofmann, M.; Lange, J. M.; Sagawe, A. (2014). "Plate interactions of Laurussia and Gondwana during the formation of Pangaea—Constraints from U–Pb LA–SF–ICP–MS detrital zircon ages of Devonian and Early Carboniferous siliciclastics of the Rhenohercynian zone, Central European Variscides". Gondwana Research. 25 (4): 1484–1500. Bibcode:2014GondR..25.1484E. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2013.05.018.

- Ernst, R. E.; Bleeker, W.; Söderlund, U.; Kerr, A. C. (2013). "Large Igneous Provinces and supercontinents: Toward completing the plate tectonic revolution". Lithos. 174: 1–14. Bibcode:2013Litho.174....1E. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2013.02.017. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- Gheerbrant, E.; Rage, J. C. (2006). "Paleobiogeography of Africa: how distinct from Gondwana and Laurasia?". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 241 (2): 224–246. Bibcode:2006PPP...241..224G. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.03.016.

- Keeley, J. E. (2012). "Ecology and evolution of pine life histories" (PDF). Annals of Forest Science. 69 (4): 445–453. doi:10.1007/s13595-012-0201-8. S2CID 18013787. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- Li, Z. X.; Bogdanova, S. V.; Collins, A. S.; Davidson, A.; De Waele, B.; Ernst, R. E.; Fitzsimons, I. C. W.; Fuck, R. A.; Gladkochub, D. P.; Jacobs, J.; Karlstrom, K. E.; Lul, S.; Natapov, L. M.; Pease, V.; Pisarevsky, S. A.; Thrane, K.; Vernikovsky, V. (2008). "Assembly, configuration, and break-up history of Rodinia: A synthesis" (PDF). Precambrian Research. 160 (1–2): 179–210. Bibcode:2008PreR..160..179L. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2007.04.021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Lu, M.; Lu, Y.; Ikejiri, T.; Hogancamp, N.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Q.; Carroll, R.; Çemen, I.; Pashin, J. (2019). "Geochemical evidence of First Forestation in the southernmost euramerica from Upper Devonian (Famennian) Black shales". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 7581. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.7581L. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-43993-y. PMC 6527553. PMID 31110279.

- McKerrow, W. S.; Mac Niocaill, C.; Ahlberg, P. E.; Clayton, G.; Cleal, C. J.; Eagar, R. M. C. (2000). "The late Palaeozoic relations between Gondwana and Laurussia". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 179 (1): 9–20. Bibcode:2000GSLSP.179....9M. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2000.179.01.03. S2CID 129789533. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- McCullough, J. M.; Moyle, R. G.; Smith, B. T.; Andersen, M. J. (2019). "A Laurasian origin for a pantropical bird radiation is supported by genomic and fossil data (Aves: Coraciiformes)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 286 (1910): 20190122. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.0122. PMC 6742990. PMID 31506056.

- Meert, J. G. (2012). "What's in a name? The Columbia (Paleopangaea/Nuna) supercontinent" (PDF). Gondwana Research. 21 (4): 987–993. Bibcode:2012GondR..21..987M. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2011.12.002. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- Metcalfe, I. (1999). "Gondwana dispersion and Asian accretion: an overview". In Metcalfe, I. (ed.). Gondwana Dispersion and Asian Accretion. IGCP 321 final results volume. Rotterdam: A.A. Balkema. pp. 9–28. doi:10.1080/08120099608728282. ISBN 90-5410-446-5.

- Milner, A. C.; Milner, A. R.; Evans, S. E. (2000). "Amphibians, reptiles and birds: a biogeographical review". In Culver, S. J.; Rawson, P. F. (eds.). Biotic Response to Global Change-The Last Million Years. Cambridge University Press. pp. 316–332. ISBN 0-511-04068-7.

- Nikishin, A. M.; Ziegler, P. A.; Abbott, D.; Brunet, M. F.; Cloetingh, S. A. P. L. (2002). "Permo–Triassic intraplate magmatism and rifting in Eurasia: implications for mantle plumes and mantle dynamics". Tectonophysics. 351 (1–2): 3–39. Bibcode:2002Tectp.351....3N. doi:10.1016/S0040-1951(02)00123-3. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- Olsen, P. E. (1997). "Stratigraphic record of the early Mesozoic breakup of Pangea in the Laurasia-Gondwana rift system" (PDF). Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 25 (1): 337–401. Bibcode:1997AREPS..25..337O. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.25.1.337. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Parrish, J. T. (1993). "Climate of the supercontinent Pangea". The Journal of Geology. 101 (2): 215–233. Bibcode:1993JG....101..215P. doi:10.1086/648217. S2CID 128757269. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Rey, P.; Burg, J. P.; Casey, M. (1997). "The Scandinavian Caledonides and their relationship to the Variscan belt". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 121 (1): 179–200. Bibcode:1997GSLSP.121..179R. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.1997.121.01.08. S2CID 49353621. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Rogers, J. J.; Santosh, M. (2004). Continents and supercontinents. p. 653. Bibcode:2004GondR...7..653R. doi:10.1016/S1342-937X(05)70827-3. ISBN 9780195347333.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Scotese, C. R. (2009). "Late Proterozoic plate tectonics and palaeogeography: a tale of two supercontinents, Rodinia and Pannotia". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 326 (1): 67–83. Bibcode:2009GSLSP.326...67S. doi:10.1144/SP326.4. S2CID 128845353. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- Seton, M.; Müller, R. D.; Zahirovic, S.; Gaina, C.; Torsvik, T.; Shephard, G.; Talsma, A.; Gurnis, M.; Maus, S.; Chandler, M. (2012). "Global continental and ocean basin reconstructions since 200Ma". Earth-Science Reviews. 113 (3): 212–270. Bibcode:2012ESRv..113..212S. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2012.03.002. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Sahney, S.; Benton, M. J.; Falcon-Lang, H. J. (2010). "Rainforest collapse triggered Pennsylvanian tetrapod diversification in Euramerica" (PDF). Geology. 38 (12): 1079–1082. doi:10.1130/G31182.1. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- Stampfli, G. M. (2000). "Tethyan oceans" (PDF). Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 173 (1): 1–23. Bibcode:2000GSLSP.173....1S. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2000.173.01.01. S2CID 219202298. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- Torsvik, T. H.; Cocks, L. R. M. (2004). "Earth geography from 400 to 250 Ma: a palaeomagnetic, faunal and facies review" (PDF). Journal of the Geological Society. 161 (4): 555–572. Bibcode:2004JGSoc.161..555T. doi:10.1144/0016-764903-098. S2CID 128812370. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Torsvik, T. H.; Smethurst, M. A.; Meert, J. G.; Van der Voo, R.; McKerrow, W. S.; Brasier, M. D.; Sturt, B. A.; Walderhaug, H. J. (1996). "Continental break-up and collision in the Neoproterozoic and Palaeozoic—a tale of Baltica and Laurentia" (PDF). Earth-Science Reviews. 40 (3–4): 229–258. Bibcode:1996ESRv...40..229T. doi:10.1016/0012-8252(96)00008-6. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- Torsvik, T. H.; Van der Voo, R.; Preeden, U.; Mac Niocaill, C.; Steinberger, B.; Doubrovine, P. V.; van Hinsbergen, D. J. J.; Domeier, M.; Gaina, C.; Tohver, E.; Meert, J. G.; McCausland, P. J. A.; Cocks, R. M. (2012). "Phanerozoic polar wander, palaeogeography and dynamics" (PDF). Earth-Science Reviews. 114 (3–4): 325–368. Bibcode:2012ESRv..114..325T. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2012.06.007. hdl:10852/62957. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- Yarmolyuk, V. V.; Kovalenko, V. I.; Sal'nikova, E. B.; Nikiforov, A. V.; Kotov, A. B.; Vladykin, N. V. (2006). "Late Riphean rifting and breakup of Laurasia: data on geochronological studies of ultramafic alkaline complexes in the southern framing of the Siberian craton". Doklady Earth Sciences. 404 (7): 1031–1036. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Zhao, G.; Cawood, P. A.; Wilde, S. A.; Sun, M. (2002). "Review of global 2.1–1.8 Ga orogens: implications for a pre-Rodinia supercontinent". Earth-Science Reviews. 59 (1–4): 125–162. Bibcode:2002ESRv...59..125Z. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(02)00073-9.

- Zhao, G.; Sun, M.; Wilde, S. A.; Li, S. (2004). "A Paleo-Mesoproterozoic supercontinent: assembly, growth and breakup". Earth-Science Reviews. 67 (1–2): 91–123. Bibcode:2004ESRv...67...91Z. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2004.02.003.

- Zhao, G.; Wang, Y.; Huang, B.; Dong, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, G.; Yu, S. (2018). "Geological reconstructions of the East Asian blocks: From the breakup of Rodinia to the assembly of Pangea". Earth-Science Reviews. 186: 262–286. Bibcode:2018ESRv..186..262Z. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2018.10.003. S2CID 134171828. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- Ziegler, P. A. (1988). Laurussia—the old red continent. Devonian of the World: Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on the Devonian System — Memoir 14, Volume I: Regional Syntheses. pp. 15–48.

- Ziegler, P. A. (2012). Evolution of Laurussia: A study in Late Palaeozoic plate tectonics. Springer. ISBN 9789400904699.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

_political.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)