The Carnival of the Animals

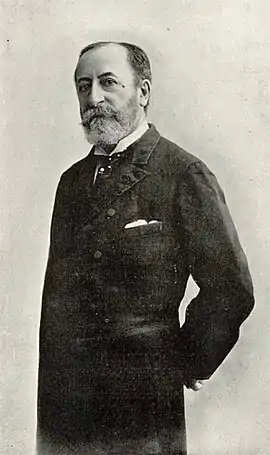

The Carnival of the Animals (Le Carnaval des animaux) is a humorous musical suite of fourteen movements, including "The Swan", by the French composer Camille Saint-Saëns. The work, about 25 minutes in duration, was written for private performance by two pianos and chamber ensemble; Saint-Saëns prohibited public performance of the work during his lifetime, feeling that its frivolity would damage his standing as a serious composer. The suite was published in 1922, the year after his death. A public performance in the same year was greeted with enthusiasm, and the work has remained among his most popular. In addition to the original version for chamber ensemble, the suite is frequently performed with a full orchestral complement of strings.

History

Following a disastrous concert tour of Germany in 1885–86, Saint-Saëns withdrew to a small Austrian village, where he composed The Carnival of the Animals in February 1886.[1] From the beginning he regarded the work as a piece of fun. On 9 February 1886 he wrote to his publishers Durand in Paris that he was composing a work for the coming Shrove Tuesday, and confessing that he knew he should be working on his Third Symphony, but that this work was "such fun" ("... mais c'est si amusant!"). He had apparently intended to write the work for his students at the École Niedermeyer de Paris,[2] but it was first performed at a private concert given by the cellist Charles Lebouc on 3 March 1886:

A few days later, a second performance was given at Émile Lemoine's chamber music society La Trompette, followed by another at the home of Pauline Viardot with an audience including Franz Liszt, a friend of the composer, who had expressed a wish to hear the work. There were other performances, typically for the French mid-Lent festival of Mi-Carême. All those performances were semi-private, except for one at the Société des instruments à vent in April 1892, and "often took place with the musicians wearing masks of the heads of the various animals they represented".[3] Saint-Saëns was adamant that the work would not be published in his lifetime, seeing it as detracting from his "serious" composer image. He relented only for the famous cello solo The Swan, which forms the penultimate movement of the work, and which was published in 1887 in an arrangement by the composer for cello and solo piano (the original uses two pianos).

Saint-Saëns specified in his will that the work should be published posthumously. Following his death in December 1921 it was published by Durand in Paris in April 1922; the first public performance was given on 25 February 1922 by the Concerts Colonne, conducted by Gabriel Pierné.[4] It was rapturously received. Le Figaro reported:

The Carnival of the Animals has since become one of Saint-Saëns's best-known works, played in the original version for eleven instruments, or more often with the full string section of an orchestra. Frequently a glockenspiel substitutes for the rare glass harmonica.[6][7]

Music

The suite is scored for two pianos, two violins, viola, cello, double bass, flute (and piccolo), clarinet (C and B♭), glass harmonica, and xylophone.[8] There are fourteen movements, each representing a different animal or animals:

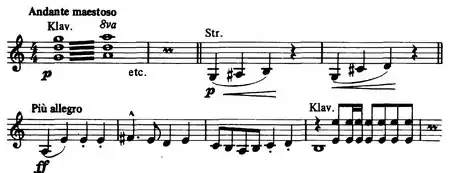

I. Introduction et marche royale du lion (Introduction and Royal March of the Lion)

Strings and two pianos: the introduction begins with the pianos playing a bold tremolo, under which the strings enter with a stately theme. The pianos play a pair of glissandos going in opposite directions to conclude the first part of the movement. The pianos then introduce a march theme that they carry through most of the rest of the introduction. The strings provide the melody, with the pianos occasionally taking low chromatic scales in octaves which suggest the roar of a lion, or high ostinatos. The two groups of instruments switch places, with the pianos playing a higher, softer version of the melody. The movement ends with a fortissimo note from all the instruments used in this movement.

II. Poules et coqs (Hens and Roosters)

Strings (except cello and double bass), two pianos and clarinet: this movement is centered around a "pecking" theme played by the pianos and strings, reminiscent of chickens pecking at grain. The clarinet plays a small solo above the strings; the piano plays a very fast theme based on the rooster's crowing cry.

III. Hémiones (animaux véloces) (Wild Asses (Swift Animals))

Two pianos: the animals depicted here are quite obviously running, an image induced by the constant, feverishly fast up-and-down motion of both pianos playing figures in octaves. These are dziggetai, donkeys that come from Tibet and are known for their great speed.

IV. Tortues (Tortoises)

Strings and piano: a satirical movement which opens with a piano playing a pulsing triplet figure in the higher register. The strings play a slow rendition of the famous "Galop infernal" (commonly called the Can-can) from Offenbach's comic opera Orphée aux enfers (Orpheus in the Underworld).

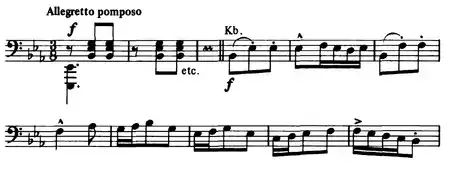

V. L'Éléphant (The Elephant)

Double bass and piano: this section is marked Allegro pomposo, the great caricature for an elephant. The piano plays a waltz-like triplet figure while the bass hums the melody beneath it. Like "Tortues," this is also a musical joke—the thematic material is taken from the Scherzo from Mendelssohn's incidental music to A Midsummer Night's Dream and Berlioz's "Dance of the Sylphs" from The Damnation of Faust. The two themes were both originally written for high, lighter-toned instruments (flute and various other woodwinds, and violin, accordingly); the joke is that Saint-Saëns moves this to the lowest and heaviest-sounding instrument in the orchestra, the double bass.

VI. Kangourous (Kangaroos)

Two pianos: the main figure here is a pattern of "hopping" chords (made up of triads in various positions) preceded by grace notes in the right hand. When the chords ascend, they quickly get faster and louder, and when the chords descend, they quickly get slower and softer.

VII. Aquarium

Violins, viola, cello (string quartet), two pianos, flute, and glass harmonica. The melody is played by the flute, backed by the strings, and glass harmonica on top of tumultuous, glissando-like runs and arpeggios in pianos. These figures, plus the occasional glissando from the glass harmonica towards the end—often played on celesta or glockenspiel—are evocative of a peaceful, dimly lit aquarium.

VIII. Personnages à longues oreilles (Characters with Long Ears)

Two violins: this is the shortest of all the movements. The violins alternate playing high, loud notes and low, buzzing ones (in the manner of a donkey's braying "hee-haw"). Music critics have speculated that the movement is meant to compare music critics to braying donkeys.[9]

IX. Le Coucou au fond des bois (The Cuckoo in the Depths of the Woods)

Two pianos and clarinet: the pianos play large, soft chords while the clarinet plays a single two-note ostinato; a C and an A♭, mimicking the call of a cuckoo bird. Saint-Saëns states in the original score that the clarinetist should be offstage.

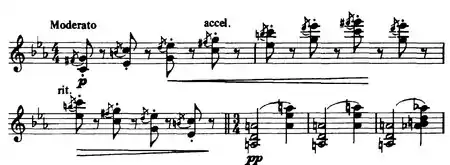

X. Volière (Aviary)

Strings, pianos and flute: the high strings take on a background role, providing a buzz in the background that is reminiscent of the background noise of a jungle. The cellos and basses play a pickup cadence to lead into most of the measures. The flute takes the part of the bird, with a trilling tune that spans much of its range. The pianos provide occasional pings and trills of other birds in the background. The movement ends very quietly after a long ascending chromatic scale from the flute.

XI. Pianistes (Pianists)

Strings and two pianos: this humorous movement (satirizing pianists as animals) is a glimpse of what few audiences ever get to see: the pianists practicing their finger exercises and scales. The scales of C, D♭, D and E♭ are covered. Each one starts with a trill on the first and second note, then proceeds in scales with a few changes in the rhythm. Transitions between keys are accomplished with a blasting chord from all the instruments between scales. In some performances, the later, more difficult, scales are deliberately played increasingly out of time. The original edition has a note by the editors instructing the players to imitate beginners and their awkwardness.[10] After the four scales, the key changes back to C, where the pianos play a moderate speed trill-like pattern in thirds, in the style of Charles-Louis Hanon or Carl Czerny, while the strings play a small part underneath. This movement is unusual in that the last three blasted chords do not resolve the piece, but rather lead into the next movement.

XII. Fossiles (Fossils)

Strings, two pianos, clarinet, and xylophone: here, Saint-Saëns mimics his own composition, the Danse macabre, which makes heavy use of the xylophone to evoke the image of skeletons dancing, the bones clacking together to the beat. The musical themes from Danse macabre are also quoted; the xylophone and the violin play much of the melody, alternating with the piano and clarinet. Allusions to "Ah! vous dirai-je, Maman" (better known in the English-speaking world as Twinkle Twinkle Little Star), the French nursery rhymes "Au clair de la lune", and "J'ai du bon tabac" (the second piano plays the same melody upside down [inversion]), the popular anthem "Partant pour la Syrie", as well as the aria "Una voce poco fa" from Rossini's The Barber of Seville can also be heard. The musical joke in this movement, according to Leonard Bernstein's narration on his recording of the work with the New York Philharmonic, is that the musical pieces quoted are the fossils of Saint-Saëns's time.

XIII. Le cygne (The Swan)

Two pianos and cello: a slowly moving cello melody (which evokes the swan elegantly gliding over the water) is played over rippling sixteenths in one piano and rolled chords in the other.

A staple of the cello repertoire, this is one of the best-known movements of the suite, usually in the version for cello with solo piano which was the only publication from this suite in Saint-Saëns's lifetime.

A short ballet solo, The Dying Swan, was choreographed in 1905 by Mikhail Fokine to this movement and performed by Anna Pavlova. Pavlova gave some 4,000 performances of the dance and "swept the world."[11]

XIV. Final (Finale)

Full ensemble: the finale opens on the same trills in the pianos as in the introduction, but soon the wind instruments, the glass harmonica and the xylophone join in. The strings build the tension with a few low notes, leading to glissandi by the piano before the lively main melody is introduced. The Finale is somewhat reminiscent of an American carnival of the 19th century, with one piano always maintaining a bouncy eighth-note rhythm. Although the melody is relatively simple, the supporting harmonies are ornamented in the style that is typical of Saint-Saëns' compositions for piano -- dazzling scales, glissandi and trills. Many of the previous movements are quoted here from the introduction, the lion, the donkeys, hens, and kangaroos. The work ends with a series of six "Hee Haws" from the donkeys, as if to say that the donkey has the last laugh, before the final strong group of C major chords.

Musical allusions

As the title suggests, the work is programmatical and zoological. It progresses from the first movement, Introduction et marche royale du lion, through portraits of elephants and donkeys ("Personages with Long Ears") to a finale reprising many of the earlier motifs.

Several of the movements are of humorous intent:

- Poules et coqs uses the theme of Rameau's harpsichord piece La poule ("The Hen") from his Suite in G major, but in a less elegant mood.[6]

- Tortues makes use of the well-known "Galop infernal" from Offenbach's comic opera Orpheus in the Underworld, playing the usually breakneck-speed melody at a slow, drooping pace.[2][12]

- L'éléphant uses a theme from Berlioz's "Danse des sylphes" (from his work The Damnation of Faust) played in a much lower register than usual as a double bass solo. The piece also quotes the Scherzo from Mendelssohn's A Midsummer Night's Dream.[2][13]

- The Personnages à longues oreilles section is thought to be directed at music critics: they are also supposedly the last animals heard during the finale, braying.[2][6]

- Pianistes depicts piano students labouring over their scales in Hanon- and Czerny-style exercises.[6][12]

- Fossiles quotes Saint-Saëns's own Danse macabre as well as three nursery rhymes, "J'ai du bon tabac," "Ah! vous dirai-je, Maman" (Twinkle Twinkle Little Star) and "Au clair de la lune," also the song "Partant pour la Syrie" and Rossini's aria, "Una voce poco fa" from The Barber of Seville.[2][13]

Verses

In 1949 Ogden Nash wrote a set of humorous verses to accompany each movement for a Columbia Masterworks recording of Carnival of the Animals conducted by Andre Kostelanetz. They were recited by Noël Coward; Kostelanetz and Coward performed the suite with Nash's verses with the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall, New York, in 1956.[14]

Nash's verses, with their topical references (e.g. to President Truman's piano playing) became dated,[6] and later writers have written new words to accompany the suite, including Johnny Morris,[6] Jeremy Nicholas,[6] Jack Prelutsky,[15] John Lithgow,[16] and Michael Morpurgo, whose version was recorded in 2020.

Recordings

Various recordings of the Carnival of the Animals have been created. Some notable ones are:

Alternative recordings

- In 1982, the Philip Jones Brass Ensemble recorded an arrangement for brass instruments by Peter Reeve.[22]

- A parody of the work entitled "Carnival of the Animals, Part Two" was recorded by "Weird Al" Yankovic and Wendy Carlos in 1988, with new verses written by Yankovic about a different cast of animals such as the shark and the poodle.[23]

- In 1993, an all-star cast recording was released on CD by Dove Audio[24] performed by the Hollywood Chamber Orchestra conducted by Lalo Schifrin with all proceeds going to charity. Readers included Arte Johnson (Introduction and Finale), Charlton Heston (Royal March of The Lion), James Earl Jones (Hens and Roosters), Betty White (Wild Donkeys), Lynn Redgrave (Tortoises), William Shatner (The Elephant), Joan Rivers (Kangaroos), Ted Danson (Aquarium), Lily Tomlin (Characters with Long Ears), Deborah Raffin (The Cuckoo), Audrey Hepburn (Aviary), Dudley Moore (Pianists), Walter Matthau (Fossils) and Jaclyn Smith (The Swan).

- In 1996, a surf rock cover of "Aquarium" was used as the on-ride soundtrack of the original Space Mountain ride layout at Disneyland before its 2005 renovation. It featured guitar riffs by Dick Dale.[25]

- For a ballet to Saint-Saëns's suite, choreographed by Christopher Wheeldon and presented by New York City Ballet, John Lithgow wrote a narration. The storyline is that a mischievous boy slips away from his teacher during a trip to a museum of natural history and, once the museum is shut, sees all the people he knows transformed into animals. An audio recording was made in 2004 by members of Chamber Music Los Angeles, conducted by Bill Elliot, with the narration spoken by Lithgow.[16]

- In 2021, the Los Angeles Philharmonic streamed the piece at the Hollywood Bowl with Yuja Wang and David Fung on piano, conducted by Gustavo Dudamel. 4 animal folktales were narrated by El Sistema students from around the world - Martin (9), Arão (12), Afra (14), and Maya (8).[26]

- In 2016, The Wiggles released The Carnival of the Animals, with narration written and performed by Simon Pryce and the music performed by the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra.

- In 2023, Chronatic Quartet released Karneval der Tiere, a crossover pop-rock-jazz arrangement by the Quartet's pianist Benedikt ter Braak for violin, double bass, piano and drums (trap set).

Notes and references

Notes

- Originally released (1975) with Nash's verses recited by Hermione Gingold.[18] Subsequently reissued without narration.

- Maurice André, Jacques Cazauran, Guy-Joel Cipriani, Michel Debost, Claude Desurmont, Alain Moglia, Gerard Perotin, Trio à cordes français

- Alain Marion, flute; Michel Arrignon, clarinet; Michel Cals, glockenspiel; Michel Cerutti, xylophone; Régis Pasquier, violin I; Yan Pascal Tortelier, violin II; Gérard Caussé, viola; Yo-Yo Ma, cello; Gabin Lauridon, double bass.

- Also released without narration.[19]

- Irena Grafenauer, flute; Eduard Brunner, clarinet; Gidon Kremer, violin; Isabelle van Keulen, violin; Tabea Zimmermann, viola; Mischa Maisky, cello; Georg Hortnagel, double bass; Markus Steckeler, xylophone; Edith Salmen-Weber, glockenspiel

- Rebecca Hirsch, Beatrice Harper, violins; Terry Nettle, viola; Jonathan Williams, cello; Rodney Slatford, double bass; Nicholas Vallis-Davies, flute/piccolo; Angela Malsbury, clarinet; Annie Oakley, xylophone; James Strebing, glockenspiel.

- Paul Edmund-Davies (flute), Andrew Marriner (clarinet), Alexander Barantschik and Ashley Arbuckle (violins), Alexander Taylor (viola), Ray Adams (cello), Paul Marrion (double-bass), Ray Northcott (percussion)

- This recording features virtuoso harmonica player Tommy Reilly playing on a mouth organ instead of a glass harmonica. This mistake was noted and acknowledged by music journalist Fritz Spiegl in a 1984 dictionary of musical ephemera.[20]

- Also released without narration

- German narration spoken by Peter Ustinov

- Renaud Capuçon, Gautier Capuçon, David Guerrier, Esther Hoppe, Florent Jodelet, Marie-Pierre Langlamet, Paul Meyer, Béatrice Muthelet, Emmanuel Pahud and Janne Saksala

- This recording is in a reorchestrated version

- Narration written and spoken by Jack Prelutsky

References

- Stegemann, p. 42

- Saint-Saëns, third unnumbered introductory page

- Blakeman, p. 117

- Rattner, pp. 185ff

- Banès, Anton. "Les Concerts" Archived 27 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Le Figaro, 27 February 1922, p. 5

- Nicholas, Jeremy. "The Gramophone Collection", Gramophone, October 2019, pp. 116–121

- "Le carnaval des animaux (Saint-Saëns, Camille)" Archived 19 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine, IMSLP. Retrieved 27 June 2021

- Saint-Saëns, title page

- "Carnival of the Animals", The Listener, 18: 104, 14 July 1937, archived from the original on 27 June 2021, retrieved 30 March 2011

- "Les exécutants devront imiter le jeu d'un débutant et sa gaucherie." "Complete full score" (PDF). Paris: Durand & Cie. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- Frankenstein, Alfred, The Carnival of the Animals (liner notes), vol. Capitol SP 8537 and reissued on Seraphim S-60214

- Griffiths, p. 147

- "Saint-Saens: Carnival of the Animals Program Notes, Jan 1, 1929 – Dec 31, 1960" Archived 20 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, New York Philharmonic archives. Retrieved 26 June 2021

- Coward, p. 316

- Notes to San Diego Symphony CD SDS-1001 OCLC SDS-1001

- OCLC 56770131

- "Carnival of the Animals", Naxos Music Library. Retrieved 26 June 2021 (subscription required) "Naxos Music Library". Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - OCLC 21827232

- OCLC 68930501

- "'The Carnival of the Animals' Features a Glass Harmonica. This Orchestra Forgot the Glass. | WQXR Editorial". WQXR. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- "Carnival | The Kanneh-Masons". Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- OCLC 60248672

- OCLC 19021977

- ISBN 1-55800-586-2

- "Dick Dale, Guitarist on Space Mountain's Soundtrack, Dies". 18 March 2019. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- "LA Phil Media launches second season of sound/stage". Hollywood Bowl. 23 February 2021. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

Sources

- Blakeman, Edward (2005). Taffanel: Genius of the Flute. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517098-6.

- Coward, Noël (1982). Payn, Graham; Morley, Sheridan (eds.). The Noël Coward Diaries (1941–1969). London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-297-78142-4.

- Griffiths, Paul (2004). The Penguin Companion to Classical Music. London and New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-100924-7.

- Ratner, Sabina Teller (2002). Camille Saint-Saëns, 1835–1921: A Thematic Catalogue of his Complete Works, Volume I: The Instrumental Works. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816320-6.

- Saint-Saëns, Camille (1957) [1922]. Le Carnaval des animaux: grande fantaisie zoologique. Paris: Durand. OCLC 31227464.

- Stegemann, Michael (1991). Camille Saint-Saëns and the French solo concerto from 1850 to 1920. Lanham: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-0-93-134035-2..

External links

- The Carnival of the Animals: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Video Performance of Le Cygne by Julian Lloyd Webber

- 2011 recording for organ and piano combined, by David Owen Norris and David Coram

- NY Theatre Ballet Children's Study Guide (PDF), featuring Ogden Nash verses