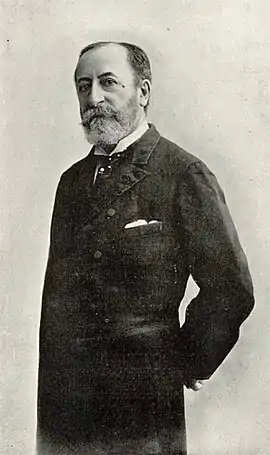

Violin Sonata No. 1 (Saint-Saëns)

The Violin Sonata No. 1 in D minor, Op. 75, was written by Camille Saint-Saëns in October 1885. Dedicated to Martin Pierre Marsick, it was premiered on 9 January 1886 in Paris. The sonata has been called one of Saint-Saëns' neglected masterpieces.

| Violin Sonata No. 1 | |

|---|---|

| Violin sonata by Camille Saint-Saëns | |

| Key | D minor |

| Opus | 75 |

| Composed | October 1885 |

| Dedication | Martin Pierre Marsick |

| Published | December 1885 (Durand) |

| Duration | 21 minutes |

| Movements | four |

| Scoring |

|

| Premiere | |

| Date | 9 January 1886 |

| Location | La Trompette, Paris |

| Performers |

|

History

The violin sonata was a form Saint-Saëns was familiar with: he had completed a Violin Sonata in B♭ major in 1842 – when he was just six years old – and abandoned another Violin Sonata in F major dating from around 1850–1851 after the second movement. These juvenile works remained unpublished until 2021.[1]

In August 1885, Saint-Saëns wrote to his publisher Durand that he intended to compose a "grand duo for piano and violin" in time for a planned tour of England. By 13 October, the sonata was completed, and he received a considerable fee of 1,200 francs.[2] It was premiered four days later in Huddersfield by the composer and Otto Peiniger and repeated in Leeds and London.[lower-alpha 1]

The work was dedicated to Martin Pierre Marsick, a violinist and professor at the Paris Conservatoire, to commemorate their tour of Switzerland. The first performance in Paris was given by Saint-Saëns and Marsick on 9 January 1886 at the chamber music society La Trompette, which Saint-Saëns frequented.

Structure

| External audio | |

|---|---|

| Performed by Renaud Capuçon and Bertrand Chamayou | |

The sonata consists of four movements in two sections; the first and second as well as the third and forth movements are joined together (attacca).[3] Saint-Saëns had used this form – a fast opening movement leading into a slow movement, followed by a scherzo and a finale – in his fourth piano concerto before, and would use it again in his third symphony.[2]

- Allegro agitato

- The opening movement is held in sonata form. The time signature of the first theme alternates between 6

8 and 9

8, giving it a sense of urgency.[4]

- The second theme is more simple and straightforward, but seems to be in a four-beat time signature, despite being marked in 6

8. It is briefly developed in the piano in 2

4 time, before the 6

8 signature returns with the main theme in the dominant.[4]

- The opening movement is held in sonata form. The time signature of the first theme alternates between 6

- Adagio

- The oscillation between the time signatures continues in the three-part Adagio (3

4). For instance, the middle section presents a four-beat rhythm rather than a three-beat rhythm.[4]

- The oscillation between the time signatures continues in the three-part Adagio (3

- Allegretto moderato

- The Allegretto moderato is a lively scherzo, in which the 3

8 time signature is clearly emphasized.[4]

- The melody of the B section draws from the second theme of the first movement.[4]

- The Allegretto moderato is a lively scherzo, in which the 3

- Allegro molto

- The Allegro molto (

) is held in the style of a perpetuum mobile, repeatedly interrupted, first by a new theme, then by the second theme of the first movement.[4]

) is held in the style of a perpetuum mobile, repeatedly interrupted, first by a new theme, then by the second theme of the first movement.[4]

- The Allegro molto (

The playing time of the sonata is around 21 minutes.[4]

Legacy

In a letter to Durand on 18 November 1885, Saint-Saëns remarked on the sonata's technical difficulty, suggesting that only a legendary creature would be able to master the final movement: "I wonder with terror what this sonata will become under the bow of my no less ordinary than extraordinary violinists; it will be called the 'hippogriff sonata'". He was convinced that "its moment of glory has begun" and that "all the violinists will seize on it, from one end of the earth to the other".[2][3]

Saint-Saëns would later refer to the work as a "concert sonata", and his biographers have compared it to Beethoven's Kreutzer Sonata. It quickly gained popularity, and Saint-Saëns himself included it often in his own concerts. It was also promoted by pianists including Louis Diémer, Raoul Pugno and Édouard Risler, and by violinists such as Eugène Ysaÿe and Jacques Thibaud.[2] The work would later inspire Marcel Proust, who mentions it in Jean Santeuil, written in the 1890s. It appears to be related to the fictional Vinteuil Sonata in the novel In Search of Lost Time.[4]

The work was arranged for cello and piano by Ferdinando Ronchini (1911), and for harp and violin by Clara Eissler (1907).[3]

Jeremy Nicholas has called the first violin sonata a neglected masterpiece, alongside the Septet and the Piano Quartet.[5]

References

- Guilloux, Fabien; Médicis, François de, eds. (2021). Saint-Saëns, Camille. Works for Violin and Piano (1): Sonatas for Violin and Piano. Bärenreiter. ISMN 979-0-006-54154-6.

- Jost, Peter (2013). Saint-Saëns. Sonate Nr. 1 d-Moll Opus 75. Munich: G. Henle Verlag. ISMN 9790201805726.

- Ratner, Sabina Teller (2002). Camille Saint-Saëns, 1835–1922: A Thematic Catalogue of his Complete Works, Volume 1: The Instrumental Works. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 179–182. ISBN 978-0-19-816320-6.

- Lenort, Bernhard (1998). Ingeborg, Allihn (ed.). Kammermusikführer (in German). Stuttgart: Metzler Publishing. p. 521. ISBN 978-3-476-00980-7.

- Nicholas, Jeremy. "Camille Saint-Saëns". BBC Music Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- The date of the first performance is hinted at by Saint-Saëns in a letter from Leeds.