Le Courrier français (1884–1914)

Le Courrier français was an illustrated weekly founded and edited by Jules Roques. It appeared from 1884 to 1914.[1]

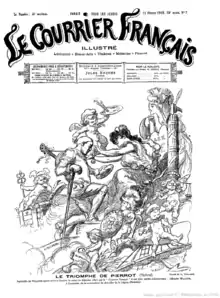

Cover of 15 February 1906 | |

| Founded | 1884 |

|---|---|

| Final issue | 1914 |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

History

.jpg.webp)

Under the direction of Jules Roques, Le Courrier français became the most representative satirical organ of the time.[2] Notable writers included Maurice Bouchor, Raoul Ponchon, Georges Montorgueil, Hugues Delorme and Jean Lorrain. Illustrators included Adolphe Willette, David Ossipovitch Widhopff, Jean-Louis Forain, Jules Chéret, Hermann-Paul, Henri Pille and Pierre Jeannot.[2] The magazine included sections on literature, fine arts, theater, medicine and finance.

Until 1895 the newspaper represented the light and sarcastic spirit of fin de siècle Paris, and welcomed elite illustrators who met every evening at the Rat Mort café in Montmartre.[lower-alpha 1] From 1885 Jules Roques welcomed the Incohérents. Raoul Ponchon published his famous "rhymed Gazettes" there, satirical and light pieces on news items. Henri Pille presented the manners of the time from a middle-aged viewpoint. Adolphe Willette, responsible for illustrating most of the cover pages, was a lover of Montmartre and finely depicted Pierrots and Harlequins.

From 1887 Jules Roques, Adolphe Willette and other artists organized the famous masked balls of Le Courrier. These were not designed as venues for showing off amusing costumes, but as meetings of groups of symbolic figures, illustrating a theme that was planned and announced in advance. These balls helped to revive the Paris Carnival, which had been interrupted after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the Siege of Paris and the bloody suppression of the Paris Commune. The preparatory drawings published in the Courier for these balls encouraged female participants to dress very lightly, which explains the success of the events.

On 15 June 1888 Le Courrier organized the "children's ball". The jury included Jean Lorrain disguised as Saint John the Baptist, Henri Pille as a constable and Jean-Louis Forain as a policeman. The characters of the commedia dell'arte were fashionable: Pierrot, Pierrette, Harlequin and Punchinello. Pille was a favorite subject of Willette, another great illustrator of the time and contributor to the Revue illustrée and the Courrier.

Le Courrier français provoked the public with daring prints. The owner Jules Roques was always interested in commercial success, while Louis Legrand tried to give it a rustic and humanitarian aspect. The hopes raised by the Exposition Universelle of 1900 were disappointed. The tone of the journal changed with the arrival of René Georges Hermann-Paul, who attacked priests, businessmen and some of the customs of the time. Violent and ironic, he was not only the perfect illustrator of Octave Mirbeau, but also a righter of wrongs with his violent and bitter graphics. His pessimistic spirit resulted in a black art that evoked cruel scenes with acerbic captions.

Le Courrier organized several sales of drawings by its employees at the Hôtel Drouot, including one on 25 April 1904 and another on 27 January 1905 under the hammer of Raymond Pujos, auctioneer.

Other artists

Artists whose work appeared in the magazine included

- Jules Fontanez

- Oswald Heidbrinck

- Jacques Villon

- Pierre-Auguste Lamy

- Manuel Robbe

- Paul César Helleu

- Alfred Choubrac

- Auguste Roedel

Other uses of the title

The title Le Courrier français has been used by other publications.

There was a Courrier français in the days of the First French Empire edited by Louis François Auguste Cauchois-Lemaire, future editor of Le Nain jaune under the restoration. He published several literary works, including Les Comédiens sans le savoir, a novel by Honoré de Balzac in 1846.[3]

Le Courrier français was a Liberal daily paper founded in 1820 that appeared until 1851, with contributions from François Guizot, Charles de Rémusat and Achille de Salvandy.[2]

The modern Courrier français is a regional weekly that covers a dozen departments in the southwest quarter of France (Charente, Charente-maritime, Dordogne, Gironde, Landes, Lot-et-Garonne, Tarn-et-Garonne, Vienne, Vendée and Loire-Atlantique) with the title Écho de l'Ouest/Courrier français. The title is published by the group of the same name, headquartered in Bordeaux.

References

Notes

- The Rat Mort was located at the top of the Rue Pigalle. Its real name was the café Pigalle. It owes its nickname to a customer whom commented on an unpleasant odor, saying "It smells like a dead rat here."

Citations

- "Guide to the European Nineteenth-Century Rare Journals at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University". Rutgers University. March 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- Larousse encyclopédique, p. 2719.

- Histoire du texte, La Pleiade, t. VII, p. 1150.

Sources

External links

- "Le Courrier français (Paris. 1884)". Gallica. BnF. Retrieved 7 February 2014.