Le Havre's old tramway

Le Havre's tramway was built when the municipality sought to equip itself with a modern form of urban transport capable of multiplying the travel possibilities of its inhabitants, as many other French cities at the end of the 19th century did. The tramway, inaugurated in Le Havre in 1874, first horse-drawn, then electric, served until World War I, transporting over 20 million people by 1913.

| Le Havre's old tramway | |

|---|---|

| Le Havre (Seine-Maritime, Haute-Normandie) | |

| |

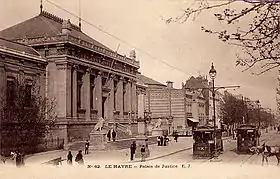

The tramway in front of the courthouse | |

| Operation | |

| Open | 1874 |

| Close | 1951 |

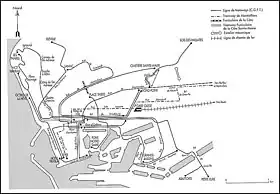

| Lines | Montiviliiers tramway (1899–1908) Côte Sainte-Marie funicular tramway (1895–1944) Côte's Funicular (1890-today) |

| Operator(s) | Compagnie Générale Française de Tramways |

| Infrastructure | |

| Propulsion system(s) | Horses (1874–1894) Electricity(1894–1951) |

| Depot(s) | Quartier de l'Eure |

| Statistics | |

| Route length | 57,414 km (35,675 mi) |

| 21600000 in 1913 | |

Competing with road transport from the 1920s onwards, it was gradually abandoned and disappeared shortly after World War II (in 1951), which was particularly destructive for the city. Following a favorable decision by the urban community in early 2007 to build an exclusive right-of-way public transport network, the tramway has been running again in Le Havre since 12 December 2012.

The beginnings of the tramway (1874–1894)

Elected representatives finally decide

Founded in 1517 by Francis I of France, the city of Le Havre experienced strong economic and demographic growth from the Second French Empire onwards, when its walls were demolished. An outport of Paris at the mouth of the Seine, Le Havre, reached by rail transport in March 1847, became increasingly industrialized as its quays lengthened. Metallurgy, shipbuilding, weaving machine and horology movement factories created jobs and led to a rapid increase in the population of a conurbation numbering over 120,000 souls in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871.

In the early 1870s, Le Havre's municipal authorities sought to modernize the city's transport system, which was unable to cope with the growing number of journeys within the city and to and from the rapidly expanding neighboring towns. In 1872, a Belgian businessman, M. de la Hault, acting on behalf of the Banque Française et Italienne, presented the municipality with a project for horse-drawn tramways, known as "American railroads",[notes 1] to replace the skeletal horsebus services in place since the July Monarchy.[1]

In 1854, an engineer from Le Havre had already submitted similar proposals to the local authorities, who had rejected them.[2] This time, the Porte Océane (commonly used name to designate Le Havre) councilors did not miss a beat and, after approval of the scope statements, awarded the establishment and operation of the new network to Belgian interests following the retrocession treaty of 3 November, 1873.[3]

The first horse-drawn tramway

Installation work proceeded apace, and on 1 February, 1874,[2] the first line between Rouen's Jetée and Octroi via Rue de Paris and Place de l'Hôtel de Ville went into service.[notes 2] It was an immediate success, with over 80,000 passengers using the line between 1 February and 14.[4]

This dynamism in urban transport led to an extension of the new mode of communication, and a second route between the town hall and the neighborhood Carreau de Sainte-Adresse via the Quatre Chemins and the Broche à Rôtir was gradually handed over to cars between 1 October, 1875, and 8 May, 1879.[2] The line serving the southern part of the town between Place Louis-XVI (Gambetta) and the former Slaughterhouses began operating on 1 May, 1880.[notes 3] Meanwhile, on 2 February, 1876,[4] the Banque Française et Italienne had transferred management of the network to the Compagnie Générale Française de Tramways (C.G.F.T).

Service on these 11,300-kilometer-long lines was provided by three types of carriage (open, double-decker and open), which were stored at the Graville depot, along with the 200 horses needed to pull them.[2]

The Belle Epoque of the tramway (1894–1914)

The electrification

With the company devoting little investment to improving its network, in the late 1880s the municipality decided to put pressure on the C.G.F.T to improve the quality of its urban services by considering the concession of new lines to competing companies. Threatened, the C.G.F.T came up with decisive arguments to protect its monopoly: lower fares, and a decision to study the electrification of the network on 28 October, 1892.[2]

The work begun in 1893 was completed on the various sections between February and August 1894,[5] before the official inauguration on 25 September.[5] There was general enthusiasm in the city of Normandy, as the people of Le Havre found the new cars clean, elegant, fast and well-lit at night; from the start of operations, tens of thousands of passengers used them every day (they carried 9,300,000 passengers in 1895).[6]

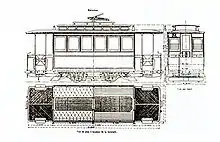

This equipment, which maintained an outstanding technical unity on the major French networks throughout the tramway's existence, was of simple, robust design, well adapted to local conditions. Built by the Compagnie Française de Matériel de Chemin de Fer in Ivry, the initial 40 tramcars were equipped with a 25 HP motor for 24 of them and two identical motors for the 16 others destined for the Sainte-Adresse line, which had steeper gradients.[7] Le Havre was the first major city in France to have a fully electrified network.

The British were impressed, and drew inspiration from it to establish the tramways of Belfast and of the Isle of Man, a fitting return in a region where English influence on railways had always been very strong.[6]

Network's extension

Following the successful introduction of electricity, the C.G.F.T embarked on a vast program to extend its lines, opening two new sections in 1896:[6]

- one facing the sea between the Octroi de la Hève and the Jetée (Hôtel Frascati) on 30 May,

(eight new railcars were delivered to provide service).

These creations set the stage for the construction of a second and third network, which were gradually built up in the years leading up to World War I.

Alongside extensions of existing routes, such as the one from Place de l'Amiral Courbet to the Grands Bassins in 1897, or those from Sainte-Adresse to Ignauval and from Les Abattoirs to Petite Eure in 1899,[8] new lines were regularly opened to the public. They linked the different parts of the city to each other, to the port and industrial zones, and to leisure and walking areas.

The following lines were thus inaugurated:[9]

- from Le Havre Station to Sanvic and Bléville via Boulevard of Strasbourg and Boulevard Maritime, 20 June, 1897.

- from Gare to Jetée via Place Gambetta, 5 January, 1901.

- Place Thiers to Notre-Dame bridge, 18 March, 1901.

- from place Gambetta to Sainte – Marie graveyard, 11 March, 1902.

- boulevard de Graville to Sanvic via Montivilliers srteet, 2 March, 1905.

- from Paris street to quai of Southampton, 2 July, 1906.

- from Octroi de la Hève to Les Phares, 30 June, 1907, extended to Ignouval, 4 June, 1908, to which should be added service to Palais des Régates and Nice havrais, provided from 27 July, 1912.

- from Rond-Point to Saint-François' Church, 15 January, 1912.

The tramway's heyday

The dynamism of the C.G.F.T, which in 1913 carried 21,600,000 passengers[10] (an increase of 132% on 1895) in its 102 power cars and 43 trailers,[10] was not only demonstrated by the opening of the new sections mentioned above. During these years of expansion, the company absorbed two of the three independent companies that also provided passenger transport in the Le Havre area. The network reached its maximum length of 57.414 kilometers.[11]

The Montivilliers tramway, which faced stiff competition from the C.G.F.T as far as Graville, was finally bought out by the latter in December 1908. Major technical modifications were necessary, and the small company's equipment stopped running between its terminus at La Jetée and Le Havre station in April 1910.[notes 5] The metric track was gradually replaced by the standard gauge track used by the Le Havre tramways in the course of the same year, 1910, when 14 new cars built by Ateliers du Nord de la France were delivered.[12]

The Côte Sainte-Marie tramway, closed since 1902 following the bankruptcy of its operator,[notes 6] was reopened in October 1911[12] under its new owner, and extended to Bois des Hallates on 1 June, 1912.[13]

Initial difficulties at closure (1914–1951)

World War I and its consequences

As in all other major French cities, the first months of the Great War saw the disorganization of the tramway service. The hiring of Belgian staff, British motormen and, from 1916 onwards, women to drive the motrices on the "easy" lines, enabled operations to return to almost normal.[12] A few cars were used to transport the wounded from the front between the station and the city's military hospitals. A provisional 3,000 m line was built in early 1917 to facilitate workers' access to the new factories located between the railway and the Tancarville canal,[14] and merely completed the connection to the Schneider factories completed in 1915.[14]

For the C.G.F.T, the end of the war marked the beginning of major economic and social difficulties. Inadequate maintenance of track and equipment between 1914 and 1918 caused a need for major investment in refurbishment, while the general rise in prices exacerbated staff grievances. The deficit, which had already reached 200,000 francs in 1917,[15] widened still further; a strike by workshop staff suspended traffic between 21 April and 23 May, 1919.[12] Faced with this delicate situation, the municipality and the C.G.F.T responded by signing a new agreement on 18 December and 20, 1921.[16] This endorsed the fare increases introduced in 1920, reduced the daily number of round trips on each line, and freed up resources for the overhaul and renovation (vestibulage) of the rolling stock.[12]

The 1920s also saw the partial or total closure of certain lines whose mileage performance did not justify refurbishment and modernization: Pont V – Abattoirs, Boulevard de Graville – Gambetta, Rond-Point – Notre-Dame, Gare Jetée, Jetée – Octroi de la Hève[17]

The difficulties of the interwar period and the introduction of the first buses and trolleybuses

Despite the deficit, which successive fare increases failed to offset, a final project to extend the network towards the Mare au Clerc district, north of the Sainte-Marie cemetery, was proposed to the local authorities in 1928.[18] This proposal was not followed up, as the time for tramways had passed; in fact, that same year, the municipality decided to introduce the first buses.[17] These, along with the trolleybuses introduced in 1938, remained confined to secondary lines until World War II, and did not constitute serious competition for the rail network, which continued to modernize its engines.[17]

The old cars were adapted to single-agent operation, while 6 new ones were delivered to the Le Havre network in 1930 by the Société Auxiliaire Française de Tramways (SAFT). Powerful (2 x 75 hp engines) and equipped with a modern, efficient braking system, they were assigned to the steep Gare – Sanvic – Bléville line.[19]

World War II and closure

World War II, having hit the Normand port so hard caused, from the perspective of transport and mobilization, serious disruption to tramway services. With the German invasion the following spring, the already reduced service was completely interrupted on 9 June[20] by the evacuation of the city's civilian population.[notes 7]

The network was gradually reopened at the request of the occupying authorities, and by December 1940 operations were back to normal, with cars carrying 40,000 passengers a day.[17] However, frequent bombings (Le Havre suffered more than 120 between 1941 and 1944) greatly disrupted tramway operations and caused considerable destruction to equipment, as in April 1942, when the Eure depot was badly hit.[17] But these were mere trifles compared with the terrible shelling carried out by Allied aircraft on 5 and 6 September, 1944, which turned the center of Le Havre into a heap of ruins[notes 8] and destroyed almost all the C.G.F.T's facilities.[17]

A brief post-war assessment gives an idea of the devastation suffered by the city of Le Havre: of the 107 railcars and 26 trailers in existence before the war, 25 and 10 respectively were still usable;[21] more than a dozen agents had perished in the bombardments, the entire infrastructure had to be rebuilt in the city center, and the depots (the central depot on rue Jules Lecesne, as well as those at Graville and de l'Eure) had all been seriously damaged.[21] Thanks to the courage and dedication of the staff, the first services were re-established as early as October 1944.

Despite considerable human and financial investment, only 8 routes were restored:[22]

- 1 – Saint-Roch – Ignauval,

- 2 – Hôtel de Ville – Graville,

- 2bis – Gare – Graville,

- 3 – Hôtel de Ville – Pont III (former terminus, place de l'Amiral-Courbet),

- 4 – Hôtel de Ville – Pont V,

- 6 – Gare – Sanvic – Bléville,

- 8 – Gare – Hôtel de Ville – Hallates.

But since the closure of the Paris network in 1938, the tramway, which had never been extensively modernized in France since 1918, fell out of favor. The oil and trucking lobbies denigrated it. Gasoline was cheap, and buses were then seen as the public transport of the future, until everyone could own their own car. In 1947, 37 modernized motorcars were put back on the road, but to no avail. On 13 July, 1948,[23] in an amendment to the 1921 agreement, the municipality decided to phase out the motorcars and replace them with trolleybuses and buses.

On 4 June, 1951,[23] amidst complete indifference,[notes 9] the last streetcar returned to the depot after a final run, putting an end to seventy-seven years of loyal service. As much as competition from road transport, the war had led to the closure of the tramway.

Other infrastructures

The Montivilliers tramway

The rail link to the small industrial town of Montivilliers, located in the Lézarde valley, had long mobilized the energies of many people in Le Havre, giving rise to discussions and projects. As early as 1868, a road locomotive service had been set up, without much success.[24]

The company Chemins de fer de l'Ouest took over, inaugurating a line between the Normandy port and Montivilliers in October 1878, the start of a coastal route linking Le Havre and Dieppe via Fécamp.[24]

However, given the inadequacy of this rail link and the inertia of the C.G.F.T, in October 1888 the municipality of Porte Océane decided to build an independent rail link between their city center and the small town.[25]

Among the many proposals submitted to the local authorities, it was that of the Compagnie Française des Voies Ferrées Économiques that attracted the most attention. This company planned to build a single-track, metric-gauge electric tramway line from the Jetée in Le Havre to the Place Assiquet (Place des Combattants 1914–1918) in Montivilliers, serving the Gare, Graville and Harfleur.[24]

This suburban railway, 14.300 kilometers long, was declared to be in the public interest on 24 February, 1897,[25] and awarded to the Compagnie du Tramway de Montivilliers. Operations began on 12 July, 1899.[24]

A fleet of twenty Thomson Houston-built 60 hp railcars, joined in 1900 by 10 open trailers,[26] served the line with departures every 10 minutes. It took them more than an hour to cover the entire route.[27]

This low average speed was due to the 20 km/h speed limit for the cars; however, "frantic" races pitted the Montivilliers equipment against that of the C.G.F.T in the Graville crossing, where the two networks were in competition.[24]

Despite the replacement of the original company by Compagnie Havraise de Tramways Électriques in February 1901,[24] the company's financial situation deteriorated rapidly under the dual impact of competition from Chemins de fer de l'Ouest and Le Havre tramways. The number of round trips had to be cut by 60% in 1904, and the number of passengers carried fell steadily (1,300,000 in 1900, 1,040,000 in 1907).[24]

Finally, on 14 December, 1908, the bankrupt Montivilliers tramway was taken over by the CGFT, which integrated it into its extensive network and converted the tracks to standard gauge.[28]

The Côte Sainte-Marie funicular tramway

Links between the lower town and the Côte were a real success; the Chemin de fer de la Côte (The coast's railway) had not yet been built when, in 1887, new projects arose to serve the Sainte-Marie cemetery and the Acacias district,[29] this time further east. One of these was submitted by Mr. Lévêque (concession-holder of the Chemin de la Côte funicular), who, after an initial setback, returned to the fray and once again wrested the decision.[29]

Declared to be in the public interest on 22 August, 1895, the 745 m-long line (including 291 m in tunnel), with a 70 m difference in height, provided a link between the bottom of Rue Clovis and the Sainte-Marie cemetery.[30] Operation was entrusted to a funicular tramway running on "reciprocating cable and self-propelled traction". The two machines that were to operate the tramway were equipped with a curious motor system. They were powered by a Serpollet boiler located on the front platform of the vehicle and connected to a Weidknecht 2-cylinder mechanism located in the center of the car.[31] Put into service on All Saints' Day 1895,[31] the route met with some initial success, but the Compagnie du Tramway Funiculaire de la Côte Sainte-Marie was soon to be disappointed. As the number of derailments multiplied, operations had to be halted on 15 March, 1896.[29] The "cable-car" had only lasted four and a half months, carrying 100,000 passengers.[29]

To avoid similar difficulties in the future, electrification was decided on the following April.[29] After laborious trials, operation resumed on 15 September, 1897[29] with an "electric and cable-free" tramway. Service was then provided by 4 Thomson Houston-built 100 hp, 50-seat motorcars, which took 4 minutes to cover this short section.[32] In fact, this was the hardest section of track in Europe for single-grip standard-gauge equipment.[33]

Although ridership on the route was increasing (375,000 passengers in 1898),[29] the financial situation was proving difficult. The original company went into liquidation in September 1898.[29] The tramway's new purchasers, Messrs Charles Philippart and Pastre, were unable to reverse the trend, and their company also went bankrupt in November 1901.[34] Nevertheless, operations continued under the aegis of a liquidator until 31 August, 1902.[34] After a nine-year stoppage, during which the equipment was completely abandoned, service resumed in 1911 with modernized equipment under the control of the C.G.F.T,[29] and the small line was integrated into the vast Le Havre tramway network, with the same fate. It never resumed operation after the terrible bombardment of September 1944.[29]

The Côte funicular

One of Le Havre's distinctive features is that it is bordered to the north by the Côte, a plateau that dominates the city center by more than 80 meters, and is traditionally a residential area. At the end of the last century, such a geographical location was bound to stimulate the imagination for a mass transit system linking the lower and upper towns. As early as 1879, a curious tramway-elevator project had been submitted to the local councillors,[35] but was rejected due to financial reasons. A few years later, in 1886, Mr. Lévêque, a Parisian engineer, presented a more serious argument for a funicular railway between Place Thiers and Rue de la Côte (Félix Faure).[36] The supposed soundness and profitability of the project led the municipality to grant the concession for this line to the Chemin de Fer de la Côte, whose principal shareholder was none other than Mr. Lévêque.

Declared to be in the public interest on 23 April, 1889,[36] and opened for service on 17 August, 1890,[36] this 343 m-long railroad, 145 m of which was viaduct track, was served by 2 cars with 48 seats, making the journey in 3 minutes.[37] In 1911, in view of the company's popular (600,000 passengers a year) and financial success,[37] it was decided to replace steam traction with electric traction. The inter-war period confirmed this success, with over 2 million passengers being transported annually in higher-capacity cars.[36] Indispensable to the local population, from 25 July, 1945 the funicular was operated directly by the town,[38] which decided to modernize it at the end of the 1960s. After extensive work between 1968 and 1972, a modern funicular was made available to the people of Le Havre.[39] New two -wheelset cars with pneumatic tires running in U-shaped[36] sections were put back into service, much to the delight of schoolchildren, the main users of this mode of transport, so rare in the north of the country. In 2021, Le Havre's funicular was be completely renovated and rebuilt.

The rolling stock

The longevity of the Le Havre network explains the presence of numerous types of equipment on the lines:[40]

- Ivry-type railcars, delivered in 1893, n°. 1 to 44, open platforms.

- Ivry-type railcars, delivered in 1896, n°. 41 to 48, open platforms.

- Montivilliers-type railcars, rebuilt by C.G.F.T in 1910, n°. 50 to 63, closed platforms.

- Montivilliers-type railcars, rebuilt by the C.G.F.T in 1910, n°. 64 to 69, open platforms.

- special-type railcars (for hills), delivered in 1896–1899, n°. 70 to 89, open platforms.

- special-type railcars (pour côtes), ex tw Côte Sainte-Marie, n° 90 to 93, open platforms.

- C.G.F.T type railcars, built in Marseille, transferred to Le Havre in 1913, n°. 94 to 103, open platforms.

- SAFT-type railcars , delivered in 1932, n°. 104 to 107, closed platforms.

- SAFT-type railcars, delivered in 1932, n°. 108 to 109, closed platforms.

The renewal

In January 2007, the Communauté d'agglomération du Havre[41] chose the tramway as its future dedicated-lane public transport system (TCSP). Service was scheduled to begin in September 2012. Initially, the network would link the city center to various districts in the upper town, and would comprise a 12.7-kilometer Y-shaped line. It would start at the beach, cross the city center and climb to the upper town via a new dedicated tunnel (approximately 680 meters long), before splitting into two branches (Mont-Gaillard on one side, Caucriauville on the other).[42] SYSTRA is prime contractor for the project.[43]

On 12 July, 2010, Alstom was selected to supply 20 new-generation Citadis trainsets.[44] The ETF (Eurovia travaux ferroviaires) consortium was awarded the contract to build the tramway platform and overhead contact line.[45] The creation of a tunnel parallel to the Jenner tunnel was awarded to the Spie Batignolles TPCI/Spie Fondations/Valerian[46] consortium.

Notes

- This type of transport appeared in the United States in 1832.

- At the town hall, this line split into two branches: one took the chaussée d'Ingouville (avenue du Président-Coty) and the Normandie street (Maréchal-Joffre streer and Aristide-Briand street), the other followed boulevard de Strasbourg and cours de la République to serve the station, joining the first route at Rond-Point.

- The Place de l'Amiral-Courbet became the ending point, replacing the former Slaughterhouses in 1888.

- At the time, the term "Abattoirs" was used to designate the new slaughterhouses located beyond Pont V in the Eure district. The passage of streetcars over Pont V was not authorized until 27 March 1899, although the infrastructure had already been in place for 3 years.

- See paragraph on the Montivilliers tramway at the end of the article.

- See paragraph on the Côte Sainte-Marie tramway at the end of the article.

- Anecdotally, C.G.F.T staff and their families were evacuated that same day in the 12 buses provided by the company director. After many adventures in the midst of the general rush, this group found itself in the Allier when the fighting stopped.

- 5,000 people from Le Havre perished due to this event.

- This contrasts with other cities (Rouen, for example) where a parade of honor was organized for the last traffic.

References

- Bertin 1994, p. 198

- Bertin 1994, p. 199

- Chapuis 1971, p. 5

- Chapuis 1971, p. 6

- Chapuis 1971, p. 44

- Bertin 1994, p. 200

- Chapuis 1971, p. 125-128 avec description détaillée du matériel.

- Chapuis 1971, p. 49

- Bertin 1994, p. 200-201 pour l'ensemble des lignes.

- Bertin 1994, p. 201

- Banaudo 2009, p. 266

- Bertin 1994, p. 203

- Chapuis 1971, p. 58

- Chapuis 1971, p. 64

- Chapuis 1971, p. 65

- Chapuis 1971, p. 66-67

- Bertin 1994, p. 204

- Chapuis 1971, p. 79

- Chapuis 1971, p. 138-141 avec description détaillée du matériel.

- Chapuis 1971, p. 86

- Chapuis 1971, p. 91

- Chapuis 1971, p. 94

- Bertin 1994, p. 205

- Bertin 1994, p. 208

- Chapuis 1971, p. 32

- Chapuis 1971, p. 36-37 avec description du matériel.

- Chapuis 1971, p. 37

- Marquis 1983, p. 96

- Bertin 1994, p. 207

- Chapuis 1971, p. 24

- Chapuis 1971, p. 25

- Chapuis 1971, p. 28

- Chapuis 1971, p. 29

- Chapuis 1971, p. 31

- Chapuis 1971, p. 18

- Bertin 1994, p. 206

- Chapuis 1971, p. 19

- Chapuis 1971, p. 22

- Marquis 1983, p. 95

- Chapuis 1971, p. 125-151

- Le projet sur site de la Communauté d'agglomération ou CODAH. Vidéo de présentation du projet à télécharger sur le site.

- Le plan de ce nouveau tramway avec quelques explications complémentaires sur le site du portail ferroviaire de Guillaume Bertrand.

- Chantier,les premiers coups de pioche sur tramway-agglo-lehavre.fr.

- Le Havre choisit le tramway Citadis d'Alstom sur mobilicites.com.

- Tramway du Havre sur le site Euravia.fr.

- Un tunnel percé par les deux bouts sur spiefondations.com.

Bibliography

- Bertin, Hervé (1994). Petits Trains et Tramways haut-normands ("Small trains and tramways of Upper Normandy") (in French). Le Mans: Cénomane/La Vie du Rail. ISBN 978-2-905596-48-2.

- Chapuis, Jacques (1971). "Les transports urbains dans l'agglomération havraise". Chemins de fer régionaux et urbains (in French) (105). ISSN 1141-7447.

- "Les transports urbains dans l'agglomération havraise". La Vie du Rail (in French) (1311). 10 October 1971.

- Banaudo, José (2009). Sur les rails de Normandie (in French). Breil-sur-Roya: Éditions du Cabri. ISBN 978-2-914603-43-0.

- Courant, René (1982). Le Temps des tramways (in French). Menton: Éditions du Cabri. ISBN 2-903310-22-X.

- Marquis, Jean-Claude (1983). Petite histoire illustrée des transports en Seine-Inférieure au 19th century (in French). Rouen: Éditions du CRDP.

- Encyclopédie générale des transports: Chemins de fer (in French). Vol. 12. Valignat: Éditions de l'Ormet. 1994. ISBN 2-906575-13-5.