Parliament of Lebanon

The Lebanese Parliament (Arabic: مجلس النواب, romanized: Majlis an-Nuwwab; French: Chambre des députés)[12] is the national parliament of the Republic of Lebanon. There are 128 members elected to a four-year term in multi-member constituencies, apportioned among Lebanon's diverse Christian and Muslim denominations but with half of the seats reserved for Christians and half reserved to Muslims per Constitutional Article 24[13]. Lebanon has universal adult suffrage. Its major functions are to elect the President of the republic, to approve the government (although appointed by the President, the Prime Minister, along with the Cabinet, must retain the confidence of a majority in the Parliament), and to approve laws and expenditure.

Lebanese Parliament مجلس النواب اللبناني Chambre des députés | |

|---|---|

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Leadership | |

| Structure | |

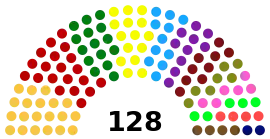

| Seats | 128 |

| |

Political groups | Caretaker Government (85)

|

Political groups | Opposition (43)

Other Opposition (6)

|

| Elections | |

| Plurality block voting with seats allocated by religion | |

Last election | 15 May 2022 |

Next election | 22 March – 22 May 2026 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Lebanese Parliament, Beirut, Lebanon | |

| Website | |

| lp.gov.lb | |

| Footnotes | |

|

|---|

|

|

On 15 May 2013, the Parliament extended its mandate for 17 months, due to the deadlock over the electoral law. And, on 5 November 2014, the Parliament enacted another extension, thus keeping its mandate for an additional 31 months, until 20 June 2017,[14] and on 16 June 2017 the Parliament in turn extended its own mandate an additional 11 months to hold elections according to a much-anticipated reformed electoral law. After extending its term for 9 years, a new parliament was elected on 6 May 2018 in the 2018 general election. According to the Lebanese constitution[15] and the electoral law of 2017,[16] elections are held on a Sunday during the 60 days preceding the end of the sitting parliament's mandate, with the next one due on a Sunday falling between March 22, 2026 and May 22, 2026.

Parliament building

The Parliament building was designed by Mardiros Altounian, who was also the architect of the Étoile clock tower. The building was completed in 1934 during the French Mandate period. Advised to build in the spirit of Lebanese tradition, the architect visited the Emirs' palaces in the Chouf Mountains. He also drew inspiration from the Oriental styles developed in Paris, Istanbul and Cairo at the turn of the 20th century. The building combines Beaux-Arts design with elements taken from local architectural tradition, including twin and triple arch windows. The limestone façade, decorated with recessed panels, arched openings, and tiers of stalactites clads a reinforced concrete frame that also supports the 20-meter (66 ft) diameter cupola covering the chamber of deputies. It represented a major technical achievement at that time.

Allocation of seats

A unique feature of the Lebanese system is the principle of "confessional distribution": all religious community has an allotted number of deputies in the Parliament.

In elections held between 1932 and 1972 (the last till after the Lebanese Civil War), seats were apportioned between Christians and Muslims in a 6:5 ratio, with various denominations of the two faiths allocated representation roughly proportional to their size. By the 1960s, Muslims had become openly dissatisfied with this system, aware that their own higher birthrate and the higher emigration rate among Christians had by this time almost certainly produced a Muslim majority, which the parliamentary distribution did not reflect. Christian politicians were unwilling to abolish or alter the system, however, and it was one of the factors in the 1975–1990 civil war. The Taif Agreement of 1989, which ended the civil war, reapportioned the Parliament to provide for equal representation of Christians and Muslims, with each electing 64 of the 128 deputies. Of which 43 are Catholic (33.5%), 27 Sunni (21%), 27 Shiite (21%), 20 Orthodox (15.6%), 8 Druze (6.2%), 2 Alawites (1.5%) and 1 Evangelical (0.8%).

Although distributed confessionally, all members, regardless of their religious faith, are elected by universal suffrage, forcing politicians to seek support from outside of their own religious communities, unless their co-religionists overwhelmingly dominate their particular constituency.

The changes stipulated by the Taif Agreement are set out in the table below:

| Confession | Before Taif | After Taif |

|---|---|---|

| Maronite Catholic | 30 | 34 |

| Eastern Orthodox | 11 | 14 |

| Melkite Catholic | 6 | 8 |

| Armenian Orthodox | 4 | 5 |

| Armenian Catholic | 1 | 1 |

| Protestant | 1 | 1 |

| Other Christian Minorities | 1 | 1 |

| Total Christians | 54 | 64 |

| Sunni | 20 | 27 |

| Shi'ite | 19 | 27 |

| Alawite | 0 | 2 |

| Druze | 6 | 8 |

| Total Muslims + Druze | 45 | 64 |

| Total | 99 | 128 |

| Electoral district under 2017 Election Law | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beirut I (East Beirut) | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Beirut II (West Beirut) | 11 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Bekaa I (Zahle) | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Bekaa II (West Bekaa-Rachaya) | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Bekaa III (Baalbek-Hermel) | 10 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Mount Lebanon I (Byblos-Kesrwan) | 8 | 1 | 7 | |||||||||

| Mount Lebanon II (Metn) | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Mount Lebanon III (Baabda) | 6 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||

| Mount Lebanon IV (Aley-Chouf) | 13 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| North I (Akkar) | 7 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| North II (Tripoli-Minnieh-Dennieh) | 11 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| North III (Bcharre-Zghorta-Batroun-Koura) | 10 | 7 | 3 | |||||||||

| South I (Saida-Jezzine) | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||

| South II (Zahrany-Tyre) | 7 | 6 | 1 | |||||||||

| South III (Marjaayoun-Nabatieh-Hasbaya-Bint Jbeil) | 11 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Total | 128 | 27 | 27 | 8 | 2 | 34 | 14 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Source: 961News |

Members

- Left: Nabih Berri, incumbent speaker.

- Right: Elias Bou Saab incumbent deputy speaker.

Political parties

Numerous political parties exist in Lebanon. Many parties are little more than ad hoc electoral lists, formed by negotiation among influential local figures representing the various confessional communities; these lists usually function only for the purpose of the election, and do not form identifiable groupings in the parliament subsequently. Other parties are personality-based, often comprising followers of a present or past political leader or warlord. Few parties are based, in practice, on any particular ideology, although in theory most claim to be.

No single party has ever won more than 12.5 percent of the total number of seats in the Parliament, and until 2005 no coalition ever won more than a third of the total. The general election held in 2005, however, resulted in a clear majority (72 seats out of 128) being won by the alliance led by Saad Hariri (son of murdered former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri); half of these were held by Hariri's own Future Movement.

Additionally, Hezbollah won 14 seats.[17]

Speaker

The Speaker of the Parliament, who by custom must be a Shi'a Muslim, is now elected to a four-year term, and is the highest office in the parliament.[18] Prior to the Taif Agreement, they are elected to a two-year term. They form part of a "troika", together with the President (required to be a Maronite Christian) and the Prime Minister (a Sunni Muslim). The privileges of the Speaker are unusually powerful, relative to other democratic systems. The current speaker is the leader of the Amal Party, Nabih Berri.[19]

Deputy Speaker

The Deputy Speaker of the Parliament of Lebanon is the second highest-ranking official of the Lebanese Parliament. The office is always attributed to a Greek Orthodox practitioner.[20]

Electoral system

The system of multi-member constituencies has been criticized over the years by many politicians, who claim that it is easy for the government to gerrymander the boundaries. The Baabda-Aley constituency, established for the 2000 election, is a case in point: the predominantly Druze area of Aley (in the east of Beirut) were combined, in a single constituency, with the predominantly Christian area of Baabda. The same thing happens in the South, meaning that although several seats within the constituency are allocated to Christians, they have to appeal to an electorate which is predominantly Muslim. Many opposition politicians, mostly Christians, have claimed that the constituency boundaries were extensively gerrymandered in the elections of 1992, 1996, 2000, 2005 and 2009. There have also been calls for the creation of a single, country-wide constituency.

See also

References

- "MPs 2022 – The Free Patriotic Movement". Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- "Boujikian dismissed from Armenian bloc for attending Monday's session". Naharnet. 7 December 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- "Factbox: What is the make-up of Lebanon's new parliament?". Reuters. 17 May 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- "Factbox: What is the make-up of Lebanon's new parliament?". Reuters. 17 May 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- "Independent National Bloc Names Mikati for Premiership". kataeb.org. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- "Political shift: National Consensus Bloc emerges with five Sunni MPs". LBCIV7. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- "The 19 Lebanese Forces MPs wrote 'the strong republic' on their papers to confirm that they did not vote for Berri". MTV Lebanon. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- Sabaghi, Dario (1 June 2023). "Have Lebanon's new opposition MPs made a difference?". newarab. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- "Lebanese Kataeb Party – حزب الكتائب اللبنانية". Kataeb Party. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- "MP Michel Mouawad announces parliamentary bloc, 'Independents and Sovereignists'". L'Orient Today. 22 June 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- "ريفي لـ'النهار': نسعى إلى ترتيب البيت السنّي وهذه عناوين حزب 'سند' وأهدافه". annahar.com. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- Official website of government. 6 June 2015.

- "ICL - Lebanon - Constitution". www.servat.unibe.ch. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Lebanon's MPs extend own terms. Al-Monitor. Published: 10 November 2014.

- "Lebanon's Constitution of 1926 with Amendments through 2004" (PDF). Constitute. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- "Lebanese electoral law 2017" (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Emigrants. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- "Hezbollah (A.k.a. Hizbollah, Hizbu'llah) - Council on Foreign Relations". www.cfr.org. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- "National Pact | Lebanon [1943] | Britannica".

- "Taif Agreement". Lebanese Parilament | مجلس النواب (in Arabic). Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- "National Pact | Lebanon [1943] | Britannica".

- Davie, May (1997). The History and Evolution of Public Spaces in Beirut Central District. Solidere. Beirut.

- Saliba, Robert (2004). Beirut City Center Recovery: The Foch-Allenby and Etoile Conservation Area. Steidel. Göttingen.

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)