Ledo Road

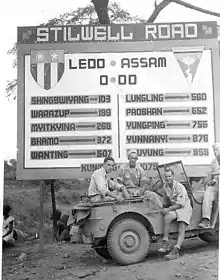

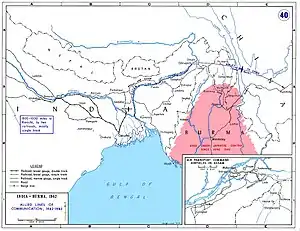

The Ledo Road (Burmese: လီဒိုလမ်းမ) was an overland connection between British India and China, built during World War II to enable the Western Allies to deliver supplies to China and aid the war effort against Japan. After the Japanese cut off the Burma Road in 1942 an alternative was required, hence the construction of the Ledo Road. It was renamed the Stilwell Road, after General Joseph Stilwell of the U.S. Army, in early 1945 at the suggestion of Chiang Kai-shek.[3] It passes through the Burmese towns of Shingbwiyang, Myitkyina and Bhamo in Kachin state.[4] Of the 1,726 kilometres (1,072 mi) long road, 1,033 kilometres (642 mi) are in Burma and 632 kilometres (393 mi) in China with the remainder in India.[5] The road had the Ledo-Pangsau Pass-Tanai (Danai)-Myitkyina--Bhamo-Mansi-Namhkam-Kunming route.

| Ledo Road | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 中印公路 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | China–India Highway | ||||||

| |||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Chinese | 史迪威公路 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Stilwell Highway | ||||||

| |||||||

To move supplies from the railheads to the Army fronts, three all-weather roads were constructed in record time during the autumn (fall) of 1943: Ledo Road in the north across three nations, which went on to connect to the Burma Road and supply China; the campaign-winning Central Front road within India from Dimapur to Imphal; and the southern road from Dohazari south of Chittagong in British India for the advance of troops to Arakan in Myanmar.[6]

In the 19th century, British railway builders had surveyed the Pangsau Pass, which is 1,136 metres (3,727 feet) high on the India-Burma border, on the Patkai crest, above Nampong, Arunachal Pradesh and Ledo, Tinsukia (part of Assam). They concluded that a track could be pushed through to Burma and down the Hukawng Valley. Although the proposal was dropped, the British prospected the Patkai Range for a road from Assam into northern Burma. British engineers had surveyed the route for a road for the first 130 kilometres (80 miles). After the British had been pushed back out of most of Burma by the Japanese, building this road became a priority for the United States. After Rangoon was captured by the Japanese and before the Ledo Road was finished, the majority of supplies to the Chinese had to be delivered via airlift over the eastern end of the Himalayan Mountains known as the Hump.

After the war, the road fell into disuse. In 2010, the BBC reported "much of the road has been swallowed up by jungle."[5]

Construction

On 1 December 1942, British General Sir Archibald Wavell, the supreme commander of the Far Eastern Theatre, agreed with American General Stilwell to make the Ledo Road an American NCAC operation. The Ledo Road was intended to be the primary supply route to China and was built under the direction of General Stilwell from the railhead at Ledo, Assam, in India,[7] to Mong-Yu road junction where it joined the Burma Road. From there trucks could continue on to Wanting on the Chinese frontier, so that supplies could be delivered to the reception point in Kunming, China. Stilwell's staff estimated that the Ledo Road route would supply 65,000 tons of supplies per month, greatly surpassing tonnage then being airlifted over the Hump to China.[8] General Claire Lee Chennault, the USAAF Fourteenth Air Force commander, thought the projected tonnage levels were overly optimistic and doubted that such an extended network of trails through difficult jungle could ever match the amount of supplies that could be delivered with modern cargo transport aircraft.[9]

The road was built by 15,000 American soldiers (60 percent of whom were African-Americans) and 35,000 local workers at an estimated cost of US$150 million (or $2 billion 2017).[10] The costs also included the loss of over 1,100 Americans lives, as many died during the construction, as well as the loss of many locals' lives.[11] The human cost of the 1,079 mile road was therefore described as "A Man A Mile".[12] As most of Burma was in Japanese hands it was not possible to acquire information as to the topography, soils, and river behaviour before construction started. This information had to be acquired as the road was constructed.

General Stilwell had organized a 'Service of Supply' (SOS) under the command of Major General Raymond A. Wheeler, a high-profile US Army engineer and assigned him to look after the construction of the Ledo Road. Major General Wheeler, in turn, assigned responsibility of base commander for the road construction to Colonel John C. Arrowsmith. Later, he was replaced by Colonel Lewis A. Pick, an expert US Army engineer.

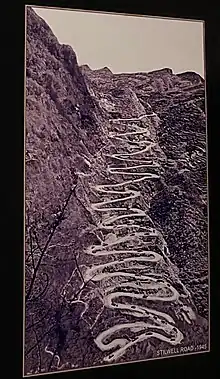

Work started on the first 166 km (103 mi) section of the road in December 1942. The road followed a steep, narrow trail from Ledo, across the Patkai Range through the Pangsau Pass (nicknamed "Hell Pass" for its difficulty), and down to Shingbwiyang, Burma. Sometimes rising as high as 1,400 m (4,600 ft), the road required the removal of earth at the rate of 1,800 cubic metres per kilometre (100,000 cubic feet per mile). Steep gradients, hairpin curves and sheer drops of 60 m (200 ft), all surrounded by a thick rain forest was the norm for this first section. The first bulldozer reached Shingbwiyang on 27 December 1943, three days ahead of schedule.

The building of this section allowed much-needed supplies to flow to the troops engaged in attacking the Japanese 18th Division, which was defending the northern area of Burma with their strongest forces around the towns of Kamaing, Mogaung, and Myitkyina. Before the Ledo road reached Shingbwiyang, Allied troops (the majority of whom were American-trained Chinese divisions of the X Force) had been totally dependent on supplies flown in over the Patkai Range. As the Japanese were forced to retreat south, the Ledo Road was extended. This was made considerably easier from Shingbwiyang by the presence of a fair weather road built by the Japanese, and the Ledo Road generally followed the Japanese trace. As the road was built, two 10 cm (4 in) fuel pipe lines were laid side-by-side so that fuel for the supply vehicles could be piped instead of trucked along the road.

After the initial section to Shingbwiyang, more sections followed: Warazup, Myitkyina, and Bhamo, 600 km (370 mi) from Ledo. At that point the road joined a spur of the old Burma road and, although improvements to further sections followed, the road was passable. The spur passed through Namkham 558 km (347 mi) from Ledo and finally at the Mong-Yu road junction, 748 km (465 mi) from Ledo, the Ledo Road met the Burma Road. To get to the Mong-Yu junction the Ledo Road had to span 10 major rivers and 155 secondary streams, averaging one bridge every 4.5 km (2.8 mi).

For the first convoys, if they turned right, they were on their way to Lashio 160 km (99 mi) to the south through Japanese-occupied Burma. If they turned left, Wanting lay 100 km (60 mi) to the north just over the China-Burma border. However, by late 1944, the road still did not reach China; by this time, tonnage airlifted over the Hump to China had significantly expanded with the arrival of more modern transport aircraft.

In late 1944, barely two years after Stilwell accepted responsibility for building the Ledo Road, it connected to the Burma Road though some sections of the road beyond Myitkyina at Hukawng Valley were under repair due to heavy monsoon rains. It became a highway stretching from Assam, India to Kunming, China 1,736 km (1,079 mi) length. On 12 January 1945, the first convoy of 113 vehicles, led by General Pick, departed from Ledo; they reached Kunming, China on 4 February 1945. In the six months following its opening, trucks carried 129,000 tons of supplies from India to China.[13] Twenty-six thousand trucks that carried the cargo (one way) were handed over to the Chinese.[13]

As General Chennault had predicted, supplies carried over the Ledo Road at no time approached tonnage levels of supplies airlifted monthly into China over the Hump.[14] However, the road complemented the airlifts. The capture of the Myitkyina airstrip enabled the Air Transport Command "to fly a more southerly route without fear of Japanese fighters, thus shortening and flattening the Hump trip with astonishing results."[15] In July 1943 the air tonnage was 5,500 rising to 8,000 in September and 13,000 in November.[16] After the capture of Myitkyina deliveries jumped from 18,000 tons in June 1944 to 39,000 in November 1944.[15]

In July 1945, the last full month before the end of the war, 71,000 tons of supplies were flown over the Hump, compared to only 6,000 tons using the Ledo Road; the airlift operation continued in operation until the end of the war, with a total tonnage of 650,000 tons compared to 147,000 for the Ledo Road.[9][14] By the time supplies were flowing over the Ledo Road in large quantities, operations in other theaters had shaped the course of the war against Japan.[8]

flying over the Hukawng Valley during the monsoon, Mountbatten asked his staff the name of the river below them. An American officer replied, "That's not a river, it's the Ledo Road."[17]

American Army units assigned to the Ledo Road

The units initially assigned to the initial section were:[18]

- 45th Engineer General Service Regiment (An African-American Unit)

- 823rd Aviation Engineer Battalion (EAB) (An African-American Unit)

In 1943 they were joined by:

- 848th EAB (An African-American Unit)

- 849th EAB (An African-American Unit)

- 858th EAB (An African-American Unit)

- 1883rd EAB (An African-American Unit)

- 236th Combat Engineer Battalion

- 1875th Combat Engineer Battalion

From the middle of April until the middle of May 1944 Company A of the 879th Airborne Engineer Battalion worked 24 hours a day on the Ledo Road, construction of their base camp and Shingbwiyang airfield, before deploying to Myitkyina to improve the facilities of an old British airfield recently recaptured from the Japanese.[19][20]

Work continued through 1944 in late December it was opened for the transport of logistics. In January 1945, four of the black EABs (along with three white battalions) continued working on the now renamed Stilwell Road, improving and widening it. Indeed, one of these African American units was assigned the task of improving the road that extended into China.[18]

Comments on the construction of the road

Winston Churchill called the project "an immense, laborious task, unlikely to be finished until the need for it has passed".

The British Field Marshal William Slim who commanded the British Fourteenth Army in India/Burma wrote of the Ledo Road:

I agreed with Stilwell that the road could be built. I believed that, properly equipped and efficiently led, Chinese troops could defeat Japanese if, as would be the case with his Ledo force, they had a considerable numerical superiority. On the engineering side I had no doubts. We had built roads over country as difficult, with much less technical equipment than the Americans would have. My British engineers, who had surveyed the trace for the road for the first eighty miles [130 km], were quite confident about that. We were already, on the Central front, maintaining great labour forces over equally gimcrack lines of communication. Thus far Stilwell and I were in complete agreement, but I did not hold two articles of his faith. I doubted the overwhelming war-winning value of this road, and, in any case, I believed it was starting from the wrong place. The American amphibious strategy in the Pacific, of hopping from island to island would, I was sure, bring much quicker results than an overland advance across Asia with a Chinese army yet to be formed. In any case, if the road was to be really effective, its feeder railway should start from Rangoon, not Calcutta.[21]

Post World War II

After Burma was liberated, the road gradually fell into disrepair. In 1955 the Oxford-Cambridge Overland Expedition drove from London to Singapore and back. They followed the road from Ledo to Myitkyina and beyond (but not to China). The book First Overland written about this expedition by Tim Slessor (1957) reported that bridges were down in the section between Pangsau Pass and Shingbwiyang. In February 1958 the Expedition of Eric Edis and his team also used the road from Ledo to Myitkyina en route to Rangoon, Singapore and Australia. Ten months later they returned in the opposite direction. In his book about this expedition The Impossible Takes a Little Longer, Edis (2008) reports that they have removed a yellow sign with India/Burma on it from the Indian/Burmese border and that they have donated it to the Imperial War Museum in London. For many years, travel into the region was also restricted by the Government of India. Because of continuous clashes between insurgents (who were seeking shelter in Burma) and the Indian Armed Forces, India imposed harsh restrictions between 1962 and the mid-1990s on travel into Burma.

Since an improvement in relations between India and Myanmar, travel has improved and tourism has begun near Pangsayu Pass (at the Lake of No Return). Recent attempts to travel the full road have met with varying results. At present the Nampong-Pangsau Pass section is passable in four-wheel drive vehicles. The road on the Burmese side is now reportedly fit for vehicular traffic. Donovan Webster reached Shingbwiyang on wheels in 2001, and in mid-2005 veterans of the Burma Star Association were invited to join a "down memory lane" trip to Shingbwiyang organised by a politically well-connected travel agent. These groups successfully travelled the road but none made any comment on the political or human rights situation on Burma afterward.

Burmese from Pangsau village saunter nonchalantly across Pangsau Pass down to Nampong in India for marketing, for the border is open despite the presence of insurgents on both sides. There are Assam Rifles and Burma Army posts at Nampong and Pangsau respectively. But the rules for locals in these border areas do not necessarily apply to westerners. The governments of both countries keep careful watch on the presence of westerners in the border areas and the land border is officially closed. Those who cross without permission risk arrest or problems with smugglers/insurgents in the area.

Current status

As of 2022, the road from Ledo to Nampong in India was a paved road, with the road going further to Pangsau Pass on India-Myanmar having restricted civilian access. From Pangsau to Tanai was a mud track, from Tanai to Myitkyina was a wide compacted-earth road maintained by a commercial plantation company, road section from Myitkyina to China border was reconstructed by a Chinese company, from China border to Kunmin is a 6 lane highway.[22]

Since the beginning of 21st century, the Burmese government focused on the reconstruction of the Ledo Road as an alternative to the existing Lashio-Kunming Burma Road. The Chinese government completed construction of the Myitkyina-Kambaiti section in 2007. Rangoon-based Yuzana Company constructed the section between Myitkyina and Tanai (Danai) which was already operational in 2011 as the company owns thousands of acres of land there for its multiple crop plantation including sugarcane and cassava.[23] India's Government, however, fears that the road may be useful to militants in North East India who have hideouts in Myanmar.[24][25][26]

In 2010 the BBC described the road: "Much of the road has been swallowed up by jungle. It is barely passable on foot and is considered too dangerous to use by many because of the presence of Burmese and Indian ethnic insurgents in the area....At present the road from Myitkyina to the Chinese border – along with the brief Indian section – is usable."[5]

In 2014, to document the status of the road the photographer Findlay Kember working on a photo feature for the South China Morning Post traveled the entire length of the road across three nations on three different trips due to not being allowed to cross the international borders. In India, there is Stilwell park in Lekhapani near Ledo to mark the beginning of the Stilwell road, a world war 2 cemetery between Jairampur and Pangsau Pass for the Chinese soldiers and labourers who built the road, a still existing bridge near Nampong nicknamed "Hell's Gate" due to treacherous conditions and landslides in the area. In Myanmar, he found villagers using WW2 gas tank as water tank in Kachin state, and the gravel road between Myitkyina and Tanai was very wide and well used but unpaved. In China, he found WW2 trenches in Songshan in Yunnan province which was a site of fierce battles between Japanese defenders and Chinese attackers in June 1944, and a brass relief honoring Chinese and American soldiers in Tengchong in Yunnan.[27] A post went viral in Philippines in 2019 which showed the current picture of 24-zigzag hairpin turns of Stilwell road on a mountain slope in Qinglong County in Guizhou province of China. It turned out to be a photo taken by Findlay Kember on his earlier trip.[28] In 2015, it was not possible to cross the border on the Ledo Road due to visa restrictions.[29] In 2015, the section from Namyun to Pangsau Pass in Burma was a "heavily rutted muddy track" through the jungle according to a BBC correspondent.[29]

In 2016, China called for restoration of Stilwell road.[30]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

See also

- Northeast Indian Railways during World War II. The Allies had problems supplying the depots at Ledo with all the logistical support needed by the Northern Front and the Chinese National Army.

- South-East Asian Theatre of World War II

- Pangsau Pass

- South East Asia Command

- The Stilwell Road featuring Ronald Reagan

- Burma campaign

Notes

- Staff. The Stilwell Road Archived 13 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, District Administration, Tinsukia (Assam) Archived 12 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Cites Sri Surendra Baruah, Margherita, Retrieved 1 October 2008

- Weidenburner. Ledo Road Signs Archived 19 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Bernstein, Richard (2014). China 1945 : Mao's revolution and America's fateful choice (First ed.). New York. p. 38. ISBN 9780307595881.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bhaumik, Subir (11 August 2009). "India not to reopen key WWII road". BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 August 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- Bhaumik, Subir. "Will the famous Indian WWII Stilwell Road reopen?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 14 August 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- Slim 1986, p. 171.

- "27°18'00.0"N 95°43'60.0"E". 27°18'00.0"N 95°43'60.0"E. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- Sherry, Mark D., China Defensive 1942-1945, United States Army Center of Military History, CBI Background. Chapter: "China Defensive Archived 29 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine"

- Xu, p. 191

- "The Ledo Road – FORGOTTEN FACTS – China-Burma-India Theater of World War II". cbi-theater.com. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- Sankar, Anand (14 February 2009). "On the road to China". Business Standard. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- "The Ledo Road – FORGOTTEN FACTS – China-Burma-India Theater of World War II". cbi-theater.com. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- Bishop, Donald M. (2 February 2005). "U.S. Embassy Marks 60th Anniversary of Ledo Road". U.S. Embassy Press Briefing and Release. American Embassy in China. Archived from the original on 11 February 2006.

- Schoenherr Steven,The Burma Front Archived 9 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, History Department at the University of San Diego Archived 3 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Tuchman, Barbara W. (1971). Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911-45. Macmillan. p. 484

- Tuchman, Barbara W. (1971). Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911-45. Macmillan. p. 376

- Moser, Don (1978). China, Burma, India. Time-Life Books. p. 139. ISBN 9780809424832.}}

- Staff. EAB in China-Burma-India Archived 31 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine, National Museum of the U.S. Air Force Archived 24 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved 1 October 2008

- 879th Airborne Engineers Official Battalion History declassified NND957710

- Zaitsoff, Mark P. (7 September 2010). Goldblatt, Gary (ed.). "879th Engineer Battalion (aviation):Engineers by Glider to Myitkyina – Company A, 879th Engineers 17 May 1944". CBI Order of Battle, linages and history. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- Slim 1986, start of Chapter XII: The Northern Front.

- India puts brakes on road to China Archived 28 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Aljazeera, 29 November 2012.

- Yuzana Company kills buffaloes with chemicals in Hukawng Valley Archived 31 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, BNI, 18 January 2011.

- Staff. Resident's homes on Ledo Road to move back 20 feet Archived 13 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Kachin News Group (KNG) Archived 8 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 7 August 2008

- Human Rights Documentation Unit, Burma Human Rights Yearbook 2007 Archived 2 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma, September 2008. p. 214

- "News18.com: CNN-News18 Breaking News India, Latest News Headlines, Live News Updates". News18. Archived from the original on 1 July 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- Passage from India: following the Stilwell Road Archived 27 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine, South China Morning Post, 20 April 2014.

- No, this photo does not show a road in the Philippines Archived 12 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine, AFP, 2019.

- Coomes, Phil (10 August 2015). "The Stilwell Road 70 years on". BBC. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- Beijing calls for restoration of Stillwell Road connecting India, China, Myanmar Archived 8 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The Hindu, 2016.

References

- Baruah, Sri Surendra. The Stilwell Road a historical review on the website of Tinsukia District in India.

- Hindah, Radhe. (NIC Changlang District Unit), A profile of Changlang District: Stilwell Road, the website of the Changlang District in India. (a mirror) A History of the road and the proposed reopening as International Highway.

- Moser, Don (1978). China, Burma, India Time-Life Books

- Slim, William Slim (1986) [1956]. Defeat into victory. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0333409566. OCLC 1391407379. Chapter XII: The Northern Front

- Staff. US Mil In China-Burma-India on the website of the National Museum of the United States Air Force

- Weidenburner, Carl Warren. Ledo Road Signs

- Xu, Guangqiu. War Wings: The United States and Chinese Military Aviation, 1929-1949, Greenwood Publishing Group (2001), ISBN 0-313-32004-7, ISBN 978-0-313-32004-0

Further reading

- Allen, Louis. Burma: The Longest War 1941-1945, Cassell; New edition (2000) ISBN 1-84212-260-6.

- Choudhuri, Atonu. Monumental neglect of war graves – Discovered in 1997, Jairampur cemetery gets entangled in red tape, The Telegraph (Calcutta), 29 January 2008

- Cochrane, S. Stilwell's Road www.chindit.net (1999–2003)

- Edis, Eric (2008). The Impossible Takes a Little Longer, Lightning Source UK Ltd (2008), ISBN 978-1-4092-0301-8.

- Gardener, S. Neal, A facsimile of the Ex-CBI Roundup July 1954 Issue, pg 20. Also additional photos of unit patches website CBI GardenerWorld

- Jenkins, Mark The Ghost Road Outside Magazine October 2003

- Khaund, Surajit. Kalam urged to reopen Stillwell Road to Reach Burma (archived from original) Mizzima News (www.mizzima.com) 28 March 2005. "Guwahati: Pursuing to reach the Burma market in the wake of improved bilateral relation, Indian Minister of state for external Affairs Bijay Krishna Handique has submitted a memorandum to President APJ Abdul Kalam for reopening of the famous Stilwell Road which connects India, Burma and China" (backup site)

- The Ledo Road; "Pick's Pike" follows Stilwell's advance in Burma Adapted for the internet from Life Magazine 14 August 1944 issue. (One of many facsimiles of original documents about the CBI on the CBI website by Carl W. Weidenburner)

- A war-time engineering miracle (backup) in The Myanmar Times Vol. 5, No. 99, 21–27 January 2002

- McRae Jr., Bennie J. 858th Engineer Aviation Battalion LWF PUBLICATIONS

- Latimer Jon, Burma: The Forgotten War, John Murray, (2004). ISBN 0-7195-6576-6. Chapter 13: 'Stilwell in the North'

- Reagan, Ronald (narraor). Stilwell Road (1945) A 51-minute documentary that, describes why and how the Ledo Road was built.

- Seay, Geraldine. "African Americans and the Ledo Stilwell Road."

- Slessor, Tim (1957) . First Overland, Signal Books Ltd (2005), ISBN 1-904955-14-2.

- Tun, Khaing Recent photos of Ledo Road website of CBI Expeditions

- Webster, Donovan. "The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theater in World War" by ; Farrar, Straus and Giroux (US), Hardback (2003), ISBN 0-374-11740-3 also Pan (UK), Paperback (2005), ISBN 0-330-42703-2

- Weidenburner, Carl Warren. The Ledo Road

- Weidenburner, Carl Warren. Mile posts and time line

- Los Angeles Times: Burma's Stilwell Road: A backbreaking World War II project is revived.

External links

- Legacy Of The Stilwell Road Archived 30 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine A Road Trip on the Stilwell Road

- The Ledo Road. General Joseph W. Stilwell's Highway to China.

| External video | |

|---|---|