Leeds Museums & Galleries

Leeds Museums and Galleries is a museum service run by the Leeds City Council in West Yorkshire. It manages nine sites and is the largest museum service in England and Wales run by a local authority.[1]

| |

| Type | Local Authority Museum Service |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Leeds |

| Location |

|

| Origins | Created by Leeds City Council to manage the city's museums and galleries |

Area served | Yorkshire |

| Services | Operating Leeds' city-owned museums and galleries |

Director | David Hopes |

Employees | 146 |

Volunteers | <200 |

| Website | museumsandgalleries |

Visitor attractions

- Abbey House Museum

- Kirkstall Abbey

Kirkstall Abbey

Kirkstall Abbey - Leeds Art Gallery

Interior Leeds Art Gallery

Interior Leeds Art Gallery - Leeds City Museum

Leeds City Museum

Leeds City Museum - Leeds Discovery Centre

Interior Leeds Discovery Centre

Interior Leeds Discovery Centre - Leeds Industrial Museum

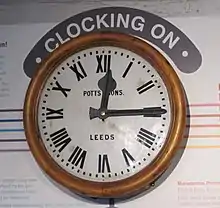

Potts clock, at Leeds Industrial Museum

Potts clock, at Leeds Industrial Museum - Lotherton Hall

Lotherton Hall

Lotherton Hall - Temple Newsam

Temple Newsam

Temple Newsam - Thwaite Mills

Thwaite Mills

Thwaite Mills

Audiences

Over 1.7 million visitors in 2018–19 visited the service's sites.[2] Visitors to Leeds and other museums in West Yorkshire contributed £34 million to the regional economy over the same time period.[3] In 2001, a review of the service found that museum learning could be far more central to its offer.[4] The service recently developed the 'Leeds Curriculum', teaching materials for schools,[5] which was awarded 'Educational Initiative of the Year' by the Museums & Heritage Awards.[6]

History

Leeds Museums & Galleries began life as the museum of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society, which opened in 1821. In 1921, the collection was purchased by Leeds Corporation, to continue as a municipal museum (Leeds City Museum).[7] In 1928, Abbey House Museum was purchased by the Leeds Corporation, as place to display social history. Kirkstall Abbey transferred to the museum service at this time. In 1941 the museum was bombed and parts of the collections were destroyed.[8] In 1982 Leeds Industrial Museum opened to the public, with Blue Peter presenters as guests of honour.[9] In 1990 Thwaite Mills opened as a museum. In 2007 Leeds Discovery Centre opened as a display store where the public can visit the collections 'behind the scenes'.

Meanwhile, Leeds Art Gallery had been founded in 1888 by public subscription. In 1921, Leeds City Council purchased Temple Newsam House as an additional venue for the arts, recognizing its historic value. These art venues were added to in 1969, with the gift of Lotherton Hall to the people of Leeds.

In 1996 the two services combined to form Leeds Museums & Galleries.[10]

Collections

Its collections comprise approximately 1.3 million objects:[11]

- Natural Science - over 800,000 globally collected specimens including taxidermy, herbaria, conchology, geology, entomology and wet material.

- Archaeology & Numismatics - worldwide collection of historical and pre-historical material including large numismatics holdings.

- dress and textiles - predominantly British collection including a large amount of garments relating to the tailoring industry in Leeds.

- Fine Art - the collection has particular strengths in the areas of 18th and early 19th century English watercolours, 20th century British Art and a modern sculpture collection more extensive than any other regional gallery in the UK.

- Industrial History - Leeds's industrial collections comprise tools, machinery, industrial products, archive ephemera, photographs and other personal records.

- Social History - this collection is particularly significant in the areas of childhood toys and games, retailing history, domestic life, musical instruments, slot machines and automata and printed ephemera.

- World Cultures - this is a significant collection area for Leeds, with over 12,000 items demonstrating the city's historic links to the wider world, and the multicultural vibe of contemporary arts and culture.

- Decorative Art - these collections can be linked to local crafts people past and present, and features major collections of furniture, ceramics, wallpapers, modern crafts, metalwork, textiles and costume.[12]

Four collection areas are Designated by Arts Council England to have national or international importance, these are: Decorative Art, Fine Art, Industrial Heritage and Natural Science.[13] They are regularly consulted by researchers, on subjects as diverse as: the genetic history of the thylacine,[14] Roman forks,[15] back-to-back housing,[16] body height of mummified pharaohs[17] and thylacine pouches.[18] The service still adds to its collections, for example through acquiring new archaeological archives.[19] Nesyamun, on display at Leeds City Museum is a widely studied Egyptian priest.

The First World War program, which ran from 2014 to 2018, examined how Leeds was affected by the First World War, worked with people across the city.[20]

Online collections

Some of Leeds Museums and Galleries' collections can be found online through a partnership with Google Arts and Culture.[21]

Internal research

Staff and volunteers undertake research on sites and collections, recent publications include:

- 'The Leeds Pals Handbook' (2018)[22]

- 'Gender and Natural Science Collections in Museums' (2017)[23]

- 'Wallpapers at Temple Newsam: 1635 to the Present' (2017)[24]

- 'Great War Britain: Leeds' (2015)[25]

External research

As well as staff and volunteers researching the sites and collections, the service has partnered on several research projects. Some examples include:

- 'The Malham Pipe: a Reassessment' - revising the dating of this important historic musical instrument from the Iron Age to the early medieval period.[26]

- 'A History of the Scientific Collections of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society's Museum in the Nineteenth Century' with University of Leeds (2019), a PhD by M. Steadman[27]

- 'Everyday Fashion in Yorkshire: 1939-99' with the University of Leeds (2019)[28]

- 'Sensory Engagements with Objects in Art Galleries' with the University of Leicester (2016), a PhD by Alexandra Woodall[29]

- 'Hospitality in a Cistercian Abbey' with University of Leeds (2015), a PhD by Richard Thomason[30]

- 'Leeds Patronising the Arts and Encouraging the Sciences' with English Heritage (2001)[31]

Funding

The service is run and primarily funded by Leeds City Council.[32] As a museum service it has a regional, national and international reputation. In 2012 the organisation achieved Major Partner Museum status from Arts Council England, which brought significant additional funding to develop its work.[33] This was continued in 2015. In 2018, Leeds Museums & Galleries was awarded National Portfolio Organisation status until 2022.[34] In 2018 9% of its workforce came from a BAME background.[35]

See also

References

- Garrard, Sheila (2008). Directory of Museums, Galleries and Buildings of Historic Interest in the UK. Routledge.

- Beecham, Richard. "Record Numbers attend Leeds Museums and Art Galleries". Yorkshire Evening Post. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- "West Yorkshire Museums Contribute Millions to Regional Economy". Leeds City Council.

- Woollard, Vicky (2012). The Responsive Museum. Ashgate. p. 272. ISBN 978-1409485032.

- 'The cultural history of the city is now at teachers' fingertips', Yorkshire Evening Post (18 June 2018).

- "2019 Winners". Museums and Heritage Awards.

- Kitson-Clark, E (1924). The History of 100 Years of Life of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. Jowett & Sowry. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Pearson, Catherine (October 2012). Museums in the Second World War. Routledge. p. 173. ISBN 9781409485032. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Brears, Peter (1989). Of Curiosities & Rare Things. Witley Press. p. 35. ISBN 0907588077.

- Roles, John (2014). Director's Choice. Scala Press. ISBN 978-1857598407.

- roles, john (2014). Director's Choice. Scala Books. ISBN 978-1857598407.

- "Leeds Museums and Galleries - Our Collections". Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "Designated Collections" (PDF). Arts Council England.

- White, Lauren (2017). "Ancient mitochondrial genomes reveal the demographic history and phylogeography of the extinct, enigmatic thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus)". Journal of Biogeography. 2017: 1–13 – via WILEY.

- Sherlock, David (2007). "Roman Forks". Archaeological Journal. 164: 249–267. doi:10.1080/00665983.2007.11020711. S2CID 220276402.

- Harrison, Joanne (2017). "The Origin, Development & Decline of Back-to-Back Housing in Leeds, 1787-1937". Industrial Archaeology Review. 39 (2). doi:10.1080/03090728.2017.1398902.

- Habicht, Michael E.; Henneberg, Maciej; Öhrström, Lena M.; Staub, Kaspar; Rühli, Frank J. (27 April 2015). "Body height of mummified pharaohs supports historical suggestions of sibling marriages". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 157 (3): 519–525. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22728. PMID 25916977.

- Sleightholme, Stephen (2012). "Description of four newly discovered". Australian Zoologist. 36 (2). doi:10.7882/AZ.2012.027.

- "Museums Collecting Archaeology (England)" (PDF). Society Museum Archaeology. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Chris Burn, 'How army of people helped Leeds remember war that changed the world', Yorkshire Evening Post (31 January 2019).

- "Leeds Museums and Galleries". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- Leeds Pals Volunteer Researchers (2018). The Leeds Pals Handbook. The History Press. ISBN 978-0750989794.

- Machin, Rebecca (2017). Museum Collections (1 ed.). Macmillan Reference USA. ISBN 978-0028663166.

- Wells-Cole, Antony (2017). Wallpapers at Temple Newsam: 1635 to the Present. Leeds Art Fund. ISBN 978-0954797959. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Pullan, Nicola (2015). Great War Britain: Leeds. The History Press. ISBN 978-0750961288. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Sermon, Richard; Todd, John F.J. (2 January 2018). "The Malham Pipe: A Reassessment of Its Context, Dating and Significance". Northern History. 55 (1): 5–43. doi:10.1080/0078172X.2018.1426178. ISSN 0078-172X. S2CID 165674780.

- Steadman, Mark (2019). "A History of the Scientific Collections of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society's Museum in the Nineteenth Century: Acquiring, Interpreting & Presenting the Natural World in the English Industrial City". University of Leeds ethesis. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "Everyday Fashion in Yorkshire". White Rose AHRC. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Sensory Engagement with Objects in Art Galleries (Thesis). hdl:2381/37942.

- Thomason, Richard. "Hospitality in a Cistercian Abbey: the Case for Kirkstall". White Rose Etheses. University of Leeds. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- "Leeds Patronising the Arts and Encouraging the Sciences". History of Art Open Bibliography. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Dixon, Andrew. "Councils Backing Culture". Arts Professional.

- Atkinson, Rebecca. "Ace Increases Number of Major Partner Museums". Museums Association.

- "Interactive NPO Map". Arts Council England.

- Picheta, Rob. "Diversity Shortcomings Underlined". Museums Association.