Noncompaction cardiomyopathy

Noncompaction cardiomyopathy (NCC) is a rare congenital disease of heart muscle that affects both children and adults.[1] It results from abnormal prenatal development of heart muscle.[2][3]

| Noncompaction cardiomyopathy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Spongiform cardiomyopathy |

| |

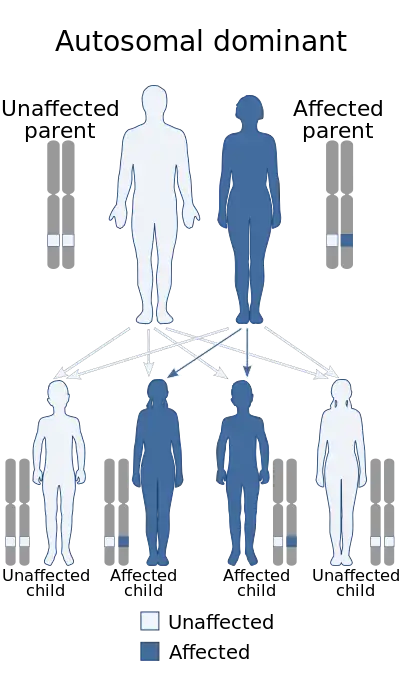

| Noncompaction cardiomyopathy is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

During development, the majority of the heart muscle is a sponge-like meshwork of interwoven myocardial fibers. As normal development progresses, these trabeculated structures undergo significant compaction that transforms them from spongy to solid. This process is particularly apparent in the ventricles, and particularly so in the left ventricle. Noncompaction cardiomyopathy results when there is failure of this process of compaction. Because the consequence of non-compaction is particularly evident in the left ventricle, the condition is also called left ventricular noncompaction. Other hypotheses and models have been proposed, none of which is as widely accepted as the noncompaction model.

Symptoms range greatly in severity. Most are a result of a poor pumping performance by the heart. The disease can be associated with other problems with the heart and the body.

Signs and symptoms

Subjects' symptoms from non-compaction cardiomyopathy range widely. It is possible to be diagnosed with the condition, yet not to have any of the symptoms associated with heart disease.[2] Likewise it is possible to have severe congestive heart failure,[3] even though the condition is present from birth, which may only manifest itself later in life.[2] Differences in symptoms between adults and children are also prevalent with adults more likely to have heart failure and children from depression of systolic function.[2]

Common symptoms associated with a reduced pumping performance of the heart include:[4]

- Breathlessness

- Fatigue

- Swelling of the ankles

- Limited physical capacity and exercise intolerance

Two conditions though that are more prevalent in noncompaction cardiomyopathy are: tachyarrhythmia which can lead to sudden cardiac death and clotting of the blood in the heart.

Complications

The presence of NCC can also lead to other complications around the heart and elsewhere in the body. These are not necessarily common complications and no paper has yet commented on how frequently these complications occur with NCC as well.

- Cardiac

- Abnormalities of the origin of the left coronary artery

- Pulmonary atresia

- Stenosis

- Right or Left ventricle obstruction

- Hypoplastic left ventricle

- Mitral regurgitation

- Neuromuscular (Pertaining to both nerves and muscles)

- Genetic related

Genetics

The American Heart Association's 2006 classification of cardiomyopathies considers noncompaction cardiomyopathy a genetic cardiomyopathy.[5] Mutations in LDB3 (also known as "Cypher/ZASP") have been described in patients with the condition.[6] There is recent information in which NCC has been seen in combination with 1q21.1 deletion Syndrome.[7] Furthermore, mutations in DES (desmin), TTN (titin), RBM20 and LMNA could be detected in a large cohort of LVNC patients.[8][9][10] Loss-of-function variants in the NONO gene have been associated with an X-linked form of noncompaction cardiomyopathy in males who also often present with developmental delays.[11] TPM1 has also been implicated in development of the disease.[12]

Diagnosis

Trabeculation of the ventricles is normal, as are prominent, discrete muscular bundles greater than 2mm. In non-compaction there are excessively prominent trabeculations. Echocardiography is the reference standard for diagnosing NCC, although it can be well defined by computer tomography scan, positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging.[13] Chin, et al., described echocardiographic method to distinguish non-compaction from normal trabeculation. They described a ratio of the distance from the trough and peak, of the trabeculations, to the epicardial surface.[14] Non-compaction is diagnosed when the trabeculations are more than twice the thickness of the underlying ventricular wall.

Transthoracic two-dimensional echocardiogram in apical four chamber and parasternal short axis at the level of both ventricles demonstrate dilatation, deep trabeculae and intertrabecular recesses in the inferior, lateral, anterior walls, middle and apical portions of the septum and apex of the left ventricle.

Transthoracic two-dimensional echocardiogram in apical four chamber and parasternal short axis at the level of both ventricles demonstrate dilatation, deep trabeculae and intertrabecular recesses in the inferior, lateral, anterior walls, middle and apical portions of the septum and apex of the left ventricle.

Differential diagnosis

Heart conditions that noncompaction cardiomyopathy needs to be distinguished from include other types of congenital heart disease (which may coexist); other causes of heart failure, like dilated cardiomyopathy; and alternative causes of increased myocardial thickness, like hypertrophic or hypertensive cardiomyopathy.[2][15]

The high number of misdiagnoses can be attributed to non-compaction cardiomyopathy being first reported in 1990; diagnosis is therefore often overlooked or delayed. Advances in medical imaging equipment have made it easier to diagnose the condition, particularly with the wider use of MRIs.

Management

One paper[16] has listed the various types of management of care that have been used for various types of NCC. These are similar to management programs for other types of cardiomyopathies which include the use of ACE inhibitors, beta blockers and aspirin therapy to relieve the pressure on the heart, surgical options such as the installation of pacemaker is also an option for those thought to be at a high risk of arrhythmia problems.

In severe cases, where NCC has led to heart failure, with resulting surgical treatment including a heart valve operation, or a heart transplant.

Prognosis

Due to non-compaction cardiomyopathy being a relatively new disease, its impact on human life expectancy is not very well understood. In a 2005 study [3] that documented the long-term follow-up of 34 patients with NCC, 35% had died at the age of 42 +/- 40 months, with a further 12% having to undergo a heart transplant due to heart failure. However, this study was based upon symptomatic patients referred to a tertiary-care center, and so were experiencing more severe forms of NCC than might be found typically in the population. Sedaghat-Hamedani et al. also showed the clinical course of symptomatic LVNC can be severe.[9] In this study cardiovascular events were significantly more frequent in LVNC patients compared with an age-matched group of patients with non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM).[9] As NCC is a genetic disease, immediate family members are being tested as a precaution, which is turning up more supposedly healthy people with NCC who are asymptomatic. The long-term prognosis for these people is currently unknown.

Epidemiology

Due to its recent establishment as a diagnosis, and it being unclassified as a cardiomyopathy according to the WHO, it is not fully understood how common the condition is. Some reports suggest that it is in the order of 0.12 cases per 100,000. The low number of reported cases though is due to the lack of any large population studies into the disease and have been based primarily upon patients with advanced heart failure. A similar situation occurred with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which was initially considered very rare; however is now thought to occur in one in every 200 to 500 people in the population, depending on the population.[17]

Again due to this condition being established as a diagnosis recently, there are ongoing discussions as to its nature, and to various points such as the ratio of compacted to non-compacted at different age stages. However it is universally understood that non-compaction cardiomyopathy will be characterized anatomically by deep trabeculations in the ventricular wall, which define recesses communicating with the main ventricular chamber. Major clinical correlates include systolic and diastolic dysfunction, associated at times with systemic embolic events.[18]

History

Non-compaction cardiomyopathy was first identified as an isolated condition in 1984 by Engberding and Benber.[19] They reported on a 33-year-old female presenting with exertional dyspnea and palpitations. Investigations concluded persistence of myocardial sinusoids (now termed non-compaction). Prior to this report, the condition was only reported in association with other cardiac anomalies, namely pulmonary or aortic atresia. Myocardial sinusoids is considered not an accurate term as endothelium lines the intertrabecular recesses.

References

- Pignatelli RH, McMahon CJ, Dreyer WJ, Denfield SW, Price J, Belmont JW, et al. (November 2003). "Clinical characterization of left ventricular noncompaction in children: a relatively common form of cardiomyopathy". Circulation. 108 (21): 2672–8. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000100664.10777.B8. PMID 14623814.

- Espinola-Zavaleta N, Soto ME, Castellanos LM, Játiva-Chávez S, Keirns C (September 2006). "Non-compacted cardiomyopathy: clinical-echocardiographic study". Cardiovascular Ultrasound. 4: 35. doi:10.1186/1476-7120-4-35. PMC 1592122. PMID 17002802.

- Jenni R, Oechslin E (2005). "Non-compaction of the Left Ventricular Myocardium – From Clinical Observation to the Discovery of a New Disease". European Cardiology Review. 1 (1): 23. doi:10.15420/ECR.2005.23. ISSN 1758-3756.

- The Cardiomyopathy Association (2007-07-23). "LV Non-compaction" (website). Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- Maron BJ, Towbin JA, Thiene G, Antzelevitch C, Corrado D, Arnett D, et al. (April 2006). "Contemporary definitions and classification of the cardiomyopathies: an American Heart Association Scientific Statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research and Functional Genomics and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working Groups; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention". Circulation. 113 (14): 1807–16. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174287. PMID 16567565.

- Vatta M, Mohapatra B, Jimenez S, Sanchez X, Faulkner G, Perles Z, et al. (December 2003). "Mutations in Cypher/ZASP in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and left ventricular non-compaction". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 42 (11): 2014–27. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.021. PMID 14662268.

- A publication is expected by Leiden University Medical Centre

- Marakhonov, Andrey V.; Brodehl, Andreas; Myasnikov, Roman P.; Sparber, Peter A.; Kiseleva, Anna V.; Kulikova, Olga V.; Meshkov, Alexey N.; Zharikova, Anastasia A.; Koretsky, Serguey N.; Kharlap, Maria S.; Stanasiuk, Caroline (June 2019). "Noncompaction cardiomyopathy is caused by a novel in‐frame desmin ( DES ) deletion mutation within the 1A coiled‐coil rod segment leading to a severe filament assembly defect". Human Mutation. 40 (6): 734–741. doi:10.1002/humu.23747. ISSN 1059-7794. PMID 30908796. S2CID 85515283.

- Sedaghat-Hamedani F, Haas J, Zhu F, Geier C, Kayvanpour E, Liss M, et al. (2017). "Clinical genetics and outcome of left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy". European Heart Journal. 38 (46): 3449–3460. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx545. PMID 29029073.

- Kulikova, Olga; Brodehl, Andreas; Kiseleva, Anna; Myasnikov, Roman; Meshkov, Alexey; Stanasiuk, Caroline; Gärtner, Anna; Divashuk, Mikhail; Sotnikova, Evgeniia; Koretskiy, Sergey; Kharlap, Maria (2021-01-19). "The Desmin (DES) Mutation p.A337P Is Associated with Left-Ventricular Non-Compaction Cardiomyopathy". Genes. 12 (1): 121. doi:10.3390/genes12010121. ISSN 2073-4425. PMC 7835827. PMID 33478057.

- Scott, Daryl A; Hernandez-Garcia, Andres; Azamian, Mahshid S; Jordan, Valerie K; Kim, Bum Jun; Starkovich, Molly; Zhang, Jinglan; Wong, Lee-Jun; Darilek, Sandra A; Breman, Amy M; Yang, Yaping (November 2016). "Congenital heart defects and left ventricular non-compaction in males with loss-of-function variants in NONO". Journal of Medical Genetics. 54 (1): 47–53. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-104039. ISSN 0022-2593. PMID 27550220. S2CID 206998226.

- Chang, Bo; Nishizawa, Tsutomu; Furutani, Michiko; Fujiki, Akira; Tani, Masanao; Kawaguchi, Makoto; Ibuki, Keijiro; Hirono, Keiichi; Taneichi, Hiromichi; Uese, Keiichiro; Onuma, Yoshiko (February 2011). "Identification of a novel TPM1 mutation in a family with left ventricular noncompaction and sudden death". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 102 (2): 200–206. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.09.009. ISSN 1096-7206. PMID 20965760.

- Kalavakunta, Jagadeesh K.; Tokala, Hemasri; Gosavi, Aparna; Gupta, Vishal (2010-01-01). "Left ventricular noncompaction and myocardial fibrosis: a case report". International Archives of Medicine. 3: 20. doi:10.1186/1755-7682-3-20. ISSN 1755-7682. PMC 2945326. PMID 20843341.

- Chin TK, Perloff JK, Williams RG, et al. (Aug 1990). "Isolated noncompaction of left ventricular myocardium. A study of eight cases". Circulation. 82 (2): 507–13. doi:10.1161/01.cir.82.2.507. PMID 2372897.

- Martínez-Baca López, F; Alonso Bravo, RM; Rodríguez Huerta, DA (2009). "Echocardiographic features of non-compaction cardiomyopathy: missed and misdiagnosed disease". Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia. 93 (2): e33–e35. doi:10.1590/S0066-782X2009000800024. PMID 19838476.

- Lorenzo Botto, MD (September 2004). "Left Ventricular Non-compacted" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-06-13.

- Semsarian, C; Ingles, J; Maron, MS (2015). "New perspectives on the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy". J Am Coll Cardiol. 65 (12): 1249–54. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.019. PMID 25814232.

- Weiford BC, Subbarao VD, Mulhern KM (2004). "Noncompaction of the ventricular myocardium". Circulation. 109 (24): 2965–71. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000132478.60674.D0. PMID 15210614.

- Engberding R, Bender F (June 1984). "Identification of a rare congenital anomaly of the myocardium by two-dimensional echocardiography: persistence of isolated myocardial sinusoids". Am. J. Cardiol. 53 (11): 1733–4. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(84)90618-0. PMID 6731322.

Further reading

- "Non-compaction of Myocardium Cardiomyopathy". Yale University. Archived from the original on September 7, 2006. Retrieved June 13, 2007.

- "Cardiomyopathy Caused by Isolated Noncompaction of the Left Ventricle in Adults". Medscape Cardiology. Retrieved June 13, 2007.

- "Non-compacted Cardiomyopathy: Clinical-Echocardiographic Study". Medscape Cardiology. Retrieved June 13, 2007.

- "Left Ventriuclar noncompaction" (PDF). Orphanet. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- "Left Ventricular Non-compaction". Baylor College of Medicine. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- Maron, Barry J.; Towbin, Jeffrey A.; Thiene, Gaetano; Antzelevitch, Charles; Corrado, Domenico; Arnett, Donna; Moss, Arthur J.; Seidman, Christine E.; Young, James B.; American Heart Association; Council On Clinical Cardiology, Heart Failure Transplantation Committee. (2006). "Contemporary Definitions and Classification of the Cardiomyopathies". American Heart Association Scientific Statement. 113 (14): 1807–1816. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174287. PMID 16567565. S2CID 6660623. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- Towbin JA, Bowles NE (2002). "The failing heart". Nature. 415 (6868): 227–33. Bibcode:2002Natur.415..227T. doi:10.1038/415227a. PMID 11805847. S2CID 2895156.

- Moreira FC, Miglioransa MH, Mautone MP, Müller KR, Lucchese F (2006). "Noncompaction of the left ventricle: a new cardiomyopathy is presented to the clinician". Sao Paulo Med J. 124 (1): 31–5. doi:10.1590/S1516-31802006000100007. PMID 16612460.

- "Non-compaction of the Left Ventricular Myocardium - From Clinical Observation to the Discovery of a New Disease". Touch Cardiology. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved June 26, 2007.