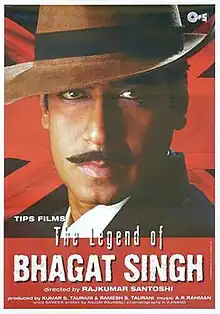

The Legend of Bhagat Singh

The Legend of Bhagat Singh is a 2002 Indian Hindi-language biographical period film directed by Rajkumar Santoshi. The film is about Bhagat Singh, a revolutionary who fought for Indian independence along with fellow members of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association. It features Ajay Devgan as the titular character along with Sushant Singh, D. Santosh and Akhilendra Mishra as the other lead characters. Raj Babbar, Farida Jalal and Amrita Rao play supporting roles. The film chronicles Singh's life from his childhood where he witnesses the Jallianwala Bagh massacre until the day he was hanged to death before the official trial dated 24 March 1931.

| The Legend of Bhagat Singh | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Rajkumar Santoshi |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | K. V. Anand |

| Edited by | V. N. Mayekar |

| Music by | A. R. Rahman |

| Distributed by | Tips Industries |

Release date |

|

Running time | 156 minutes[1] |

| Country | India |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | ₹200−250 million[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] |

| Box office | est. ₹129 million[lower-alpha 2] |

The film was produced by Kumar and Ramesh Taurani's Tips Industries on a budget of ₹200–250 million (about US$4.2–5.2 million in 2002).[lower-alpha 2] The story and dialogue were written by Santoshi and Piyush Mishra respectively, while Anjum Rajabali drafted the screenplay. K. V. Anand, V. N. Mayekar and Nitin Chandrakant Desai were in charge of the cinematography, editing and production design respectively. Principal photography took place in Agra, Manali, Mumbai and Pune from January to May 2002. The soundtrack and film score is composed by A. R. Rahman, with the songs "Mera Rang De Basanti" and "Sarfaroshi Ki Tamanna" being well received in particular.

The Legend of Bhagat Singh was released on 7 June 2002 to generally positive reviews, with the direction, story, screenplay, technical aspects, and the performances of Devgan and Sushant receiving the most attention. However, the film underperformed at the box office, grossing only ₹129 million (US$2.7 million in 2002).[lower-alpha 2] It went on to win two National Film Awards – Best Feature Film in Hindi and Best Actor for Devgn – and three Filmfare Awards from eight nominations.

Plot

Some officials take three dead bodies covered in white cloth to throw them near a river and burn it but are stopped by the villagers and unveil the bodies. Tragedy strikes when an old woman named Vidyavati also unveils a body only to find her son under the cloth and is terrified to see her son in that condition.

A great strike was held on 24 March mourning the death of those three youngsters. Meanwhile, at Malir station in Karachi, Mahatma Gandhi arrives at the station and sees his supporters praising him, except for those youngsters shouting insults against him for not saving the three youngsters, it was revealed that they were Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru respectively. They gift him a crafted black rose and explain to him the reason, Gandhiji tells them that he appreciates their feelings for the country and he could have given his life to save them, but they were on the wrong path of patriotism and didn't want to live. A youngster disagrees with his reply and says that his intention was similar to that of the British government who never wanted to free the three young revolutionaries, and added that Gandhiji never tried his best to free them. Gandhiji also says that he never supports the path of violence. The youngsters still disagreed and concluded that history will ask this question to him forever, continuing the insults for Gandhiji and praising Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru. Bhagat Singh's father, Kishan Singh secretly greets him. The story later rewinds to past events.

Bhagat Singh was born on 28 September 1907, at Banga village of Lyallpur district in Punjab Province of British India. He witnesses some British officials torturing people who were not even guilty, the young Bhagat also hears that the British officials cussed them "Bloody Indians" when he was on his father's lap who was going back after witnessing all the atrocities. At the age of 12, Bhagat takes a solemn vow to free India from the British Raj after witnessing the aftermath of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. Soon after the massacre, he learns of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi's satyagraha policies and begins to support the non-cooperation movement, in which thousands of people burn British-made clothing and abandon school, college studies, and government jobs. In February 1922, Gandhi calls off the movement after the Chauri Chaura incident. Feeling betrayed by Gandhi, Bhagat decides to become a revolutionary, and, as an adult, he goes to Cawnpore and joins the Hindustan Republican Association, a revolutionary organization, in its struggle for India's independence, ending up in prison for his activities. Singh's father, Kishen Singh, bails him out on a fee of ₹60,000 so that he can get him to run a dairy farm and marry a girl named Mannewali. Bhagat runs away from home, leaving a note saying that his love for the country comes first.

When Lala Lajpat Rai is beaten (lathi charged) to death by the police while protesting against the Simon Commission, Bhagat, along with Shivram Hari Rajguru, Sukhdev Thapar and Chandra Shekhar Azad, killed John P. Saunders (who is mistaken for James A. Scott who ordered Lala Lajpat Rai's beatdown), a British police officer, on 17 December 1928. Two days later the incident, they were in disguise to escape from the police who started an identification process with the witnesses of the murder to arrest them. Later, in Calcutta, they start to think that their efforts have gone waste and decide to make a plan for an explosion. After meeting Jatindra Nath Das who reluctantly agrees, they learn the bomb-making process and check whether it is successful. Azad starts to worry whether anything may happen to Bhagat, Bhagat is later consoled by Sukhdev and Azad reluctantly agrees. On 8 April 1929, when the British proposed the Trade Disputes and Public Safety Bills, Bhagat, along with Batukeshwar Dutt, initiate a bombing of the Central Legislative Assembly. He and Dutt throw the bombs on empty benches due to their intention to avoid causing casualties. They are subsequently arrested and tried publicly. Bhagat then gives a speech about his ideas of revolution, stating that he wanted to tell the world about the freedom fighters himself rather than let the British misrepresent them as violent people, citing this as the reason for bombing the assembly. Bhagat soon becomes more popular than Gandhi among the Indian populace, in particular the younger generation, laborers, and farmers.

In Lahore Central Jail, Bhagat and all of the other fellow prisoners, including Sukhdev and Rajguru, undertake a 116-day hunger strike to improve the conditions of Indian political prisoners. On the 63rd day, one of Bhagat's partners Jatin Das, dies of cholera in police custody as he could not bear the disease anymore. Meanwhile, Azad, whom the British had repeatedly failed to capture, is ambushed at the Alfred Park in Allahabad on 27 February 1931. The police surround the entire park leading to a shootout; refusing to be captured by the British, Azad commits suicide with the last remaining bullet in his Colt pistol.

Fearing the growing popularity of the hunger strike amongst the Indian public nationwide, Lord Irwin (the Viceroy of British India) order the re-opening of the Saunders' murder case, which leads to capital death sentences being imposed on Bhagat, Sukhdev, and Rajguru. The Indians hope that Gandhi will use his pact with Irwin as an opportunity to save Bhagat, Sukhdev, and Rajguru's lives. Irwin refuses Gandhi's request for their release. Gandhi reluctantly agrees to sign a pact that includes the clause: "Release of political prisoners except for the ones involved in violence". Bhagat, Sukhdev, and Rajguru are hanged in secrecy on 23rd March 1931 even before their trial on 24 March 1931.

Cast

- Ajay Devgan as Bhagat Singh

- Nakshdeep Singh as young Bhagat

- Sushant Singh as Sukhdev Thapar

- D. Santosh as Shivaram Rajguru

- Akhilendra Mishra as Chandra Shekhar Azad

- Raj Babbar as Kishen Singh Sandhu, Bhagat's father

- Farida Jalal as Vidyawati Kaur Sandhu, Bhagat's mother

- Amrita Rao as Mannewali, Bhagat's fiancé

- Mukesh Tewari as Khan Bahadur Mohammad Akbar, Deputy jailor at Lahore Central Jail

- Surendra Rajan as Mohandas Karamchand "M. K." Gandhi alias "Mahatma Gandhi"

- Saurabh Dubey as Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru

- Swaroop Kumar as Motilal Nehru

- Arun Patwardhan as Madan Mohan Malviya

- Kenneth Desai as Subhash Chandra Bose

- Sitaram Panchal as Lala Lajpat Rai

- Bhaswar Chatterjee as Batukeshwar Dutt alias "B. K. Dutt"

- Amit Dhawan as Bhagwati Charan Vora

- Harsh Khurana as Jai Gopal

- Kapil Sharma as Shiv Verma

- Indrani Banerjee as Durgawati Devi a.k.a. "Durga Bhabhi"

- Amitabh Bhattacharjee as Jatindra Nath Das a.k.a. "Jatin Das"

- Shish Khan as Prem Dutt

- Sanjay Sharma as Ajay Ghosh

- Raja Tomar as Mahabir Singh

- Deepak Kumar Bandhu as Ramsaran Das

- Niraj Shah as Gaya Prasad

- Pradeep Bajpai as Kishori Lal

- Aditya Verma as Des Raj

- Romie Jaspal as Sachindranath Sanyal

- Sunil Grover as Jaidev Kapoor

- Abir Goswami as Phanindra Nath Ghosh

- Pramod Pathak as Mahour

- Aashu Mohil as Hans Raj Vohra

- Manu Malik as Agya Ram

- Navin Bhaskar as Kawalnath Tiwari

- Shreyas Pandit as Surendra Nath Pandey

- Rakesh Awan as Markand

- Kiran Randhawa as police officer

- Ganesh Yadav as Ram Prasad Bismil

- Tony Mirchandani as Ashfaqulla Khan

- Padam Singh as Thakur Roshan Singh

- Ashok Sharma as Rajendra Lahiri

- Mahesh Raja as Sachindranath Bakshi

- Vikky as Mukundilal

- Piyush Chakravorthy as Banwarilal

- Vasudevan as Murari Sharma

- Narendra Rawal as Manmath Nath Gupta

- Shamsher Singh as Arjan Singh

- Oshima Rekhi as Jai Kaur

- Sukhmani Kohli as Amar Kaur

- Ankush as Kulbir Singh

- Karanbir Singh as Kultar Singh

- Renu Soni as Baddi Chachi

- Anita as Choti Chachi

- Gurucharan Channi as Chattar Singh

- Mahajan Prashant as Justice Rai Sahib

- Hayat Asif as Justice Asaf Ali

- Sardar Sohi as Leader at Jallianwala Bagh

- Rajesh Tripathi as Veerbhadra Tiwari

- Lalit Tiwari as Professor Amarnath Vidyalankar

- Shehzad Khan as Horse-cart driver Khairu

- Gil Alon as Viceroy Lord Irwin

- Ryan Jonathan as Herbert Emerson, Home Member, His Majesty's Government

- Conrad as Assistant Superintendent of Police John P. Saunders

- Tim as Superintendent of Police James Alexander Scott

- Richard as Reginald Dyer, who ordered Gurkha soldiers to open fire on an unarmed gathering of people at Jallianwala Bagh in 1919.

Production

Development

In 1998, the film director Rajkumar Santoshi read several books on the socialist revolutionary, Bhagat Singh, and felt that a biopic would help revive interest in him.[6] Although Manoj Kumar made a film about Bhagat in 1965, titled Shaheed, Santoshi felt that despite being "a great source of inspiration on the lyrics and music front", it did not "dwell on Bhagat Singh's ideology and vision".[7] In August 2000,[8] the screenwriter Anjum Rajabali mentioned to Santoshi about his work on Har Dayal, whose revolutionary activities inspired Udham Singh.[lower-alpha 3] Santoshi then persuaded Rajabali to draft a script based on Bhagat's life as he was inspired by Udham Singh.[10]

Santoshi gave Rajabali a copy of Shaheed Bhagat Singh, K. K. Khullar's biography of the revolutionary.[11][12] Rajabali said that reading the book "created an intense curiosity in me about the mind of this man. I definitely wanted to know more about him." His interest in Bhagat intensified after he read The Martyr: Bhagat Singh's Experiments in Revolution (2000) by journalist Kuldip Nayar. The following month, Rajabali formally began his research on Bhagat while admitting to Santoshi that it was "a difficult task". Gurpal Singh, a Film and Television Institute of India graduate, and internet blogger Sagar Pandya assisted him.[11] Santoshi received input from Kultar Singh, Bhagat's younger brother, who told the director he would have his full co-operation if the film accurately depicted Bhagat's ideologies.[13]

Rajabali wanted to "recreate the world that Bhagat Singh lived in", and his research required him to "not only understand the man, but also the influences on him, the politics of that era".[11] In an interview with Sharmila Taliculam of Rediff.com in the year 2000, Rajabali said that the film would "deal with Bhagat Singh, the man, rather than the freedom fighter".[10] Many aspects of Bhagat's life, including his relationship with fiancée Mannewali, were derived from Piyush Mishra's 1994 play Gagan Damama Bajyo; Mishra was subsequently credited with writing the film's dialogues.[14]

A. G. Noorani's 1996 book, The Trial of Bhagat Singh: Politics of Justice, provided the basis for the trial sequences. Gurpal obtained additional information from 750 newspaper clippings of The Tribune dated from September 1928 to March 1931, and from Bhagat's prison notebooks. These gave Rajabali "an idea of what had appealed to the man, the literary and intellectual influences that impacted him in that period".[11] By the end of the year 2000, Santoshi and Rajabali completed work on the script and showed it to Kumar and Ramesh Taurani of Tips Industries; both were impressed by it. The Taurani brothers agreed to produce the film under their banner and commence filming after Santoshi had finished his work on Lajja (2001).[15][16]

Casting

Sunny Deol was initially cast as Bhagat, but he left the project owing to schedule conflicts and differences with Santoshi over his remuneration.[17] Santoshi then preferred to cast new faces instead of established actors but was not pleased with the performers who auditioned.[10][18] Ajay Devgn (then known as Ajay Devgan) was finally chosen for the lead character because Santoshi felt he had "the eyes of a revolutionary. His introvert nature conveys loud and clear signals that there is a volcano inside him ready to burst."[7] After Devgn performed a screen test dressed as Bhagat, Santoshi was "pleasantly surprised" to see Devgn's face closely resemble Singh's and cast him in the part. The Legend of Bhagat Singh marked Devgn's second collaboration with Santoshi after Lajja.[19] Devgn called the film "the most challenging assignment" in his career.[7] He had not watched Shaheed before signing up for the project. To prepare for the role, Devgn studied all the references Santoshi and Rajabali had procured to develop the film's script. He also lost weight to more closely resemble Bhagat.[18][20]

Whatever we have read in school and learnt in history is not even 1% of the kind of person he [Bhagat] was. I don't think he got his due ... When Rajkumar Santoshi narrated the script to me, I was taken aback because this man had done so much and his motive was not just independence of India. He had predicted the challenges that we face in our country today. From riots to corruption, he had predicted that and he wanted to fight that.[21]

— Devgn on his perception of Bhagat

Santoshi chose Akhilendra Mishra to play Azad as he also resembled his character. In addition to reading Shiv Verma's Sansmritiyan, Mishra read Bhagwan Das Mahore's and Sadashiv Rao Malkapurkar's accounts of the revolutionary. Because of his astrological beliefs, he even obtained Azad's horoscope to determine his personality. In an interview with Rediff.com's Lata Khubchandani, Mishra mentioned that while informing his father about his role of Azad, he revealed to him that they originally hailed from Kanpur, the same place where Azad's ancestors were from. This piece of information encouraged Mishra to play Azad.[22]

Sushant Singh and D. Santosh (in his cinematic debut) were cast as Bhagat's friends and fellow members of the Hindustan Republican Association, Sukhdev Thapar and Shivaram Rajguru.[23] Santoshi believed their faces resembled those of the two revolutionaries.[7] To learn about their characters, Sushant, like Mishra, read Sansmritiyan while Santosh visited Rajguru's family members.[24][25] The actors were also chosen according to their characters' backgrounds. This was true in the case of Santosh and also Amitabh Bhattacharjee, who played Jatin Das, the man who devised the bomb for Bhagat and Batukeshwar Dutt. Santosh and Bhattacharjee were from Maharashtra and West Bengal like Rajguru and Das.[26] Raj Babbar and Farida Jalal were cast as Bhagat's parents, Kishen Singh and Vidyawati Kaur, while Amrita Rao played Mannewali, Bhagat's fiancée.[27]

Filming

Principal photography began in January 2002 and was completed in May.[28][29] The first schedule of filming took place in Agra and Manali following which the unit moved to the Film City studio in Mumbai.[7] According to the film's cinematographer, K. V. Anand, around 85 sets were constructed at Film City by Nitin Chandrakant Desai who was in charge of the production design, and "99 percent of the background" featured in the film was sets.[30] Desai used sepia tint throughout the film to create a period feel.[31]

Additional scenes depicting the massacre of 1919 were filmed at a set constructed to look like the Bagh as it was 83 years ago; some of them were shot between 9 pm and 6 am. The scenes at the Bagh set and other surrounding locations of Amritsar at the beginning of the film feature Nakshdeep Singh as the younger Bhagat. Santoshi selected Nakshdeep after receiving photographs of the boy from his father, Komal Singh, who played Mannewali's father.[32]

Kultar stayed with the production unit for seven days during the outdoor location shooting in Pune. Both Santoshi and Devgn appreciated the interactions they had with Kultar, noting that he provided "deep insights into his brother's life".[7][18] Kultar was pleased with the sincerity of the cast and crew and shared private letters written by Bhagat with them.[33] The song "Pagdi Sambhal Jatta" was the last part to be filmed. A sequence in the song featuring Devgn appearing between two factions of backup Bhangra dancers took three takes to be completed.[7] The Legend of Bhagat Singh was made on a budget of ₹200 – 250 million (about US$4.15 – 5.18 million in 2002).[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2]

Music

A. R. Rahman composed the soundtrack and score for The Legend of Bhagat Singh,[34] marking his second collaboration with Santoshi after Pukar. Sameer wrote the lyrics for the songs.[35] In an interview with Arthur J. Pais of Rediff.com, Rahman said that Santoshi wanted him to compose songs that would stand apart from his other projects like Lagaan (2001) and Zubeidaa (2001).[35] Rahman took care to compose the tunes for "Mera Rang De Basanti" in a slow-paced manner to avoid comparisons with the songs in Shaheed, which he and Santoshi found to be fast-paced. Rahman followed the same procedure for "Sarfaroshi Ki Tamanna". He created a softer tune, saying that the "song is pictured on men who have fasted for over a month. How can I compose a high-sounding tune for that song?"[35] Despite this, Rahman admitted that "Des Mere Des" had "some strains" from Lagaan's music.[35] Rahman took "Santoshi's commitment to the film" as a source of inspiration to make an album that was "flavorsome [sic] and different." Rahman experimented with Punjabi music more than he had done before on his previous soundtracks, receiving assistance from Sukhwinder Singh and Sonu Nigam.[35] The soundtrack was completed within two months,[36] with "Des Mere Des" recorded in an hour.[37]

The soundtrack, marketed by Tips, was released on 8 May 2002 in New Delhi.[38] The songs, especially "Mera Rang De Basanti" and "Sarfaroshi Ki Tamanna", received favourable reviews.[31][39][40] A review carried by The Hindu said that while "Sarfaroshi Ki Tamanna" had a "forceful" impact, "Mera Rang De Basanti" and "Pagdi Sambhal Jatta" were "not the boom-boom types but subtly tuned". The review praised Rahman's ability "to impart the sombre and poignant mood" in all the album's songs "so well that despite being subdued, it retains the patriotic fervour".[41] Seema Pant of Rediff.com said that "Mera Rang De Basanti" and "Mahive Mahive" were "well rendered" by their respective singers and called "Sura So Pahchaniye" an "intense track, both lyrically as well as composition wise". Pant praised Sukhwinder Singh's "exquisite rendition" of "Pagdi Sambhal Jatta" and described the duet version of "Sarfaroshi Ki Tamanna" as having "been beautifully composed". She appreciated how the "tabla, santoor and flute gives this slow and soft number a classical touch."[39] A critic from Sify said the music is "good".[42] While Pant and the Sify reviewer concurred with Rahman that "Des Mere Des" was similar to Lagaan's music,[41][42] the review in The Hindu compared the song to "Bharat Hum Ko Jaan Se Pyaara Hain" ("Thamizha Thamizha") from Roja (1992).[39]

| No. | Title | Singer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Mera Rang De Basanti" | Sonu Nigam, Manmohan Waris | 05:07 |

| 2. | "Pagdi Sambhal Jatta" | Sukhwinder Singh | 04:45 |

| 3. | "Mahive Mahive" | Alka Yagnik, Udit Narayan | 05:28 |

| 4. | "Sarfaroshi Ki Tamanna" | Sonu Nigam | 01:47 |

| 5. | "Dil Se Niklegi" | Sukhwinder Singh | 03:31 |

| 6. | "Sura So Pahchaniye" | Karthik, Raqueeb Alam, Sukhwinder Singh | 01:22 |

| 7. | "Sarfaroshi Ki Tamanna" (sad) | Sonu Nigam, Hariharan | 06:44 |

| 8. | "Des Mere Des" | Sukhwinder Singh, A. R. Rahman | 05:24 |

| Total length: | 34:08 | ||

Release

The Legend of Bhagat Singh was released on 7 June 2002 coinciding with the release of Sanjay Gadhvi's romance, Mere Yaar Ki Shaadi Hai,[43] and another film based on Bhagat, 23rd March 1931: Shaheed, which featured Bobby Deol as the revolutionary.[2][44]

A week before the film's release, Article 51 A Forum, a non-governmental organisation in Delhi, believed The Legend of Bhagat Singh to be historically inaccurate, criticising the inclusion of Mannewali as Bhagat's widow, and stating the films were made "without any research or devotion" and the filmmakers were just looking at the box-office prospects to "make spicy films based on imaginary episodes".[45] Kumar Taurani defended his film saying that he did not add Rao "for ornamental value", noting he would have opted for an established actress instead if that were the case. A press statement issued by Tips Industries said: "This girl from Manawali village loved Bhagat Singh so totally that she remained unmarried till death and was known as Bhagat Singh's widow."[46] The chief operating officer of Tips Industries, Raju Hingorani, pointed out that Kultar had authenticated the film, stating: "With his backing, why must we be afraid of other allegations?"[47]

On 29 May 2002, a 14-page petition was filed by Paramjit Kaur, the daughter of Bhagat's youngest brother, Rajinder Singh, at the Punjab and Haryana High Court to stay the release of both The Legend of Bhagat Singh and 23rd March 1931: Shaheed, alleging that they "contained distorted versions" of the freedom fighter's life. Kaur's lawyer, Sandeep Bhansal, argued that Bhagat singing a duet with Mannewali and wearing garlands were "untrue and amounted to distortion of historical facts". Two days later, the petition came up for hearing before the Judges Justice J. L. Gupta and Justice Narinder Kumar Sud; both refused to stay the films' release, observing that the petition was moved "too late and it would not be proper to stop the screening of the films".[48]

Reception

Critical response

The Legend of Bhagat Singh received generally positive critical feedback, with praise for its direction, story, screenplay, cinematography, production design and the performances of Devgn and Sushant.[3][49][50] Chitra Mahesh praised Santoshi's direction, noting in her review for The Hindu that he "shows some restraint in handling the narrative". She appreciated the film's technical aspects and Devgn's rendition, calling his interpretation of Bhagat "powerful, without being strident".[31] Writing for The Times of India, Dominic Ferrao commended Devgn, Sushant, Babbar and Mishra, saying that they all come "off with flying colours".[40] A review carried by Sify labelled the film "slick and commendable"; it also termed Devgn's portrayal of Bhagat as "fabulous" but felt he "overrides" the character and that "the supporting characters make more impact than him."[42]

In a comparative analysis of The Legend of Bhagat Singh with 23rd March 1931: Shaheed, Ziya-Us-Salam of The Hindu found the former to be a better film because of the "clearly etched out" supporting characters, while opining Devgn was more "restrained and credible" than Bobby Deol. Salam admired Sushant's performance, opining that he has "a fine screen presence, good timing and an ability to hold his own in front of more celebrated actors".[51] In a more mixed comparison, Rediff.com's Amberish K. Diwanji, despite finding The Legend of Bhagat Singh and Devgn to be the better film and actor like Salam, criticised the "constant shouting and mouthing of dialogues". He responded negatively to the inclusion of Bhagat's fiancée, pointing out the film took liberties in using this "slim" piece of information "just to have a girl sing." Diwanji, however, commended the narrative structure of The Legend of Bhagat Singh, saying that the film captured the revolutionary's life and journey well, thereby making it "worth watching and give[ing] it relevant historical background."[52]

Among overseas reviewers, Dave Kehr of The New York Times complimented the placement of the film's song sequences, especially that of "Sarfaroshi Ki Tamanna" and "Mere Rang De Basanti". Kehr called Devgn's interpretation of Bhagat "glowering" while praising Sushant's "urbane and unpredictable" rendition of Sukhdev.[53] Although Variety's Derek Elley found The Legend of Bhagat Singh to be "drawn with more warmth" and approved of Devgn's and Sushant's performances, he was not pleased with the "choppy" screenplay in the film's first half. He concluded his review by saying that the film "has a stronger lead [thespian] and richer gallery of characters that triumph over often unsubtle direction".[54]

Some of the criticism was also directed towards the treatment of Gandhi. Mahesh notes that he "appears in rather poor light" and was depicted as making "little effort" to secure a pardon for Bhagat, Sukhdev and Rajguru.[31] Diwanji concurs with Mahesh while also saying that the Gandhi–Irwin Pact as seen in the film would make the audience think that Gandhi "condemned the trio to be hanged by inking the agreement" while pointing out the agreement itself "had a different history and context."[52] Kehr believed the film's depiction of Gandhi was its "most interesting aspect". He described Surendra Rajan's version of Gandhi as "a faintly ridiculous poseur, whose policies play directly into the hands of the British" and in that aspect, he was very different from "the serene sage" portrayed by Ben Kingsley in Richard Attenborough's Gandhi (1982).[53] Like Diwanji, Elley also notes how the film denounces Gandhi by blaming him "for not trying very hard" to prevent Bhagat's execution.[54]

Box office

The Legend of Bhagat Singh had an average opening in its first week, grossing ₹57.1 million (US$1.18 million in 2002) worldwide, with ₹33 million (US$684,221 in 2002) in India alone.[2][lower-alpha 2] The film failed to cover its budget thus underperforming at the box office, collecting only ₹129.35 million (US$2.68 million in 2002) by the end of its theatrical run.[lower-alpha 2][2] Shubhra Gupta of Business Line attributed the film's commercial failure to its release on the same day as 23rd March 1931: Shaheed, opining that "the two Bhagats ate into each other's business".[3]

Accolades

At the 50th National Film Awards, The Legend of Bhagat Singh won the Best Feature Film in Hindi and Devgn received the Best Actor award.[55] The film received three nominations at the 48th Filmfare Awards and won three—Best Background Score (Rahman), Best Film (Critics) (Kumar Taurani, Ramesh Taurani) and Best Actor (Critics) (Devgn).[56]

| Award | Date of ceremony[lower-alpha 4] | Category | Recipient(s) and nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filmfare Awards | 21 February 2003 | Best Background Score | A. R. Rahman | Won | [49] [56] |

| Best Film (Critics) | Kumar Taurani, Ramesh Taurani | Won | |||

| Best Actor (Critics) | Ajay Devgn | Won | |||

| National Film Awards | 29 December 2003 | Best Feature Film in Hindi | Rajkumar Santoshi, Kumar Taurani, Ramesh Taurani | Won | [55] |

| Best Actor | Ajay Devgn | Won |

Legacy

Since its release, The Legend of Bhagat Singh has been considered one of Santoshi's best works.[57] Devgan said in December 2014 that The Legend of Bhagat Singh along with Zakhm (1998) were the best films he ever worked on in his career. He also revealed he had not seen such a good script since.[58] In 2016, the film was included in Hindustan Times's list of "Bollywood's Top 5 Biopics".[59] The Legend of Bhagat Singh was added in both the SpotBoyE and The Free Press Journal lists of Bollywood films that can be watched to celebrate India's Independence Day in 2018.[60][61] The following year, Daily News and Analysis and Zee News also listed it among the films to watch on Republic Day.[62][63]

Notes

- While the film's details on Box Office India state that the budget was ₹20 million,[2] Shubhra Gupta of Business Line says that ₹250 million was spent on the film's making.[3]

- The average exchange rate in 2002 was 48.23 Indian rupees (₹) per 1 US dollar (US$).[4]

- Udham Singh was a revolutionary responsible for the assassination of Michael O'Dwyer, the former lieutenant governor of Punjab as a response to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919.[9]

- Date is linked to the article about the awards held that year, wherever possible.

References

- "The Legend Of Bhagat Singh". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- "The Legend of Bhagat Singh". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- Gupta, Shubhra (17 June 1998). "Problem of plenty?". Business Line. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- "Rupee vs dollar: From 1990 to 2012". Rediff.com. 18 May 2012. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- Gupta, Amit Kumar (September–October 1997), "Defying Death: Nationalist Revolutionism in India, 1897–1938", Social Scientist, 25 (9/10): 3–27, doi:10.2307/3517678, JSTOR 3517678 (subscription required)

- Tips Official 2011, Clip from 01:57 to 02:27.

- Lalwani, Vickey (18 May 2002). "A revolution in his eyes". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Tips Official 2011, Clip from 01:22 to 01:24.

- Swami, Praveen (November 1997). "Jallianwala Bagh revisited". Frontline. Vol. 14, no. 22. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Taliculam, Sharmila (15 September 2000). "Legends are made of these!". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- Rajabali, Anjum. "Why Bhagat Singh? A personal quest". Legendofbhagatsingh.com. Archived from the original on 2 June 2002. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- Khullar, K. K. (1981). Shaheed Bhagat Singh. New Delhi: Hem Publishers. OCLC 644455912.

- Tips Official 2011, Clip from 01:35 to 01:56.

- K, Kannan (1 July 2002). "The play which inspired a film". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- Tips Official 2011, Clip from 01:24 to 01:39.

- "The Tricolour Envelopes The Big Screen". The Financial Express. 2 June 2002. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- Surindernath, Nisha (September 2001). "Director's special". Filmfare. Archived from the original on 13 February 2002. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Lalwani, Vickey (4 June 2002). "Who was Bhagat Singh?". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Tips Official 2011, Clip from 05:52 to 06:12.

- A. Siddiqui, Rana (28 October 2002). "Ajay Devgan: Little variety in Hindi films". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Tips Official 2011, Clip from 06:25 to 07:00.

- Khubchandani, Lata (3 June 2002). "I am related to Azad". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "D. Santosh as Rajguru". Legendofbhagatsingh.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2002. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Tips Official 2011, Clip from 07:22 to 07:41.

- Rajamani, Radhika (18 June 2002). "Full of spark". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Tips Official 2011, Clip from 09:44 to 10:13.

- "The Legend of Bhagat Singh Cast & Crew". Bollywood Hungama. 7 June 2002. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Tips Official 2011, Clip from 05:10 to 05:15.

- Salam, Ziya Us (1 February 2002). "Cashing in on the patriotic zeal". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Tips Official 2011, Clip from 05:17 to 05:42.

- Mahesh, Chitra (14 June 2002). "The Legend of Bhagat Singh". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Wadhwa, Manjula (13 July 2002). "Zeroing in On...Chhota Bhagat Singh". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Salam, Ziya Us (3 June 2002). "A non-stop show... ". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "The Legend of Bhagat Singh (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack)". iTunes. 7 June 2002. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Pais, Arthur J. (4 June 2002). "The freedom song". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Tips Official 2011, Clip from 11:40 to 11:52.

- Tips Official 2011, Clip from 13:59 to 14:06.

- "The Legend of Bhagat Singh Music Launch". Rediff.com. 9 May 2002. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Pant, Seema (18 May 2002). "In tune with patriotism". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Ferrao, Dominic (8 June 2002). "At the movies: The Legend of Bhagat Singh". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- "Chords & Notes". The Hindu. 27 May 2002. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- "The Legend of Bhagat Singh". Sify. 6 June 2002. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- "Mere Yaar Ki Shaadi Hai". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- "23rd March 1931 Shaheed". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- Singh, Onkar (29 May 2002). "Bhagat Singh is not a brand name". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Lalwani, Vickey (30 May 2002). "'There was a woman in Bhagat Singh's life'". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Singh, Onkar (4 June 2002). "The law and the martyr". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Singh, Onkar (1 June 2002). "Court refuses to grant stay". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Ausaja, S. M. M. (2009). Bollywood in Posters. Noida: Om Books International. p. 243. ISBN 978-81-87108-55-9.

- "Bhagat Singh death anniversary: Bollywood films on Indian freedom fighters". Mid-Day. 23 March 2018. Archived from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Salam, Ziya Us (10 June 2002). "History through Bollywood eyes". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Diwanji, Amberish K. (7 June 2002). "Ajay steals a march over Bobby". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Kehr, Dave (10 June 2002). "Film Review; Gandhi Is Eclipsed by Another Revolutionary Hero of India's Freedom Fight". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Elley, Derek (28 June 2002). "The Legend of Bhagat Singh / 23rd March 1931: Shaheed". Variety. Archived from the original on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- "50th National Film Awards Function 2003". Directorate of Film Festivals. pp. 32–33, 72–73. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "Filmfare Nominees and Winners" (PDF). Filmfare. pp. 113–116. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Varma, Sukanya (20 January 2004). "What makes Rajkumar Santoshi versatile?". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

Dedhia, Sonil (20 July 2018). "Sunny Deol and Rajkumar Santoshi bury the hatchet". Mid-Day. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

Kher, Ruchika (3 November 2009). "I'm the trendsetter: Raj Kumar Santoshi". Hindustan Times. Indo-Asian News Service. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019. - "There is a dearth of good scripts: Ajay Devgn". Hindustan Times. Press Trust of India. 13 December 2014. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- Vats, Rohit (30 September 2016). "Ready for Dhoni? We list Bollywood's top 5 biopics, from Bose to Shahid". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- Sur, Prateek (11 August 2018). "Independence Day Movies: Top 8 Patriotic Films To Watch On Independence Day 2018". SpotBoyE. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- "Independence Day 2018: Watch these patriotic movies to celebrate 72nd Independence day". The Free Press Journal. 14 August 2018. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- "Happy Republic Day: Swades, Rang De Basanti, Uri – 12 iconic Bollywood films that commemorate the spirit of being Indian". Daily News and Analysis. 26 January 2019. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- "Republic Day 2019: These Bollywood films will reignite the patriotic fervour in you". Zee News. 26 January 2019. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

Film

- Tips Official (18 August 2011). The Legend of Bhagat Singh – Movie Making – Ajay Devgan. YouTube (Motion picture) (in Hindi). India. Archived from the original on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)