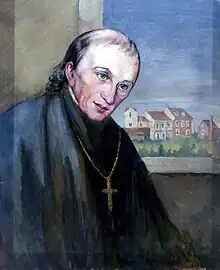

Leonard Neale

Leonard Neale SJ (October 15, 1746 – June 18, 1817) was an American Catholic prelate and Jesuit who became the second Archbishop of Baltimore and the first Catholic bishop to be ordained in the United States. While president of Georgetown College, Neale became the coadjutor bishop to John Carroll and founded the Georgetown Visitation Monastery and Academy.

Leonard Neale | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Baltimore | |

| |

| Archdiocese | Baltimore |

| Installed | December 3, 1815 |

| Term ended | June 18, 1817 |

| Predecessor | John Carroll |

| Successor | Ambrose Maréchal |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | June 5, 1773 |

| Consecration | December 7, 1800 by John Carroll |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 15, 1746 |

| Died | June 18, 1817 (aged 70) Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Buried | Georgetown Visitation Monastery |

| Denomination | Catholic Church |

| Previous post(s) |

|

| Alma mater | Colleges of St Omer, Bruges and Liège |

Neale was born in the British Province of Maryland to a prominent family that produced many Catholic leaders, including his brothers, Francis and Charles. He was educated in Europe, where he entered the Society of Jesus in 1767. Neale then volunteered to become a missionary to British Guiana in 1779. He spent four years there, before becoming discouraged by the resistance from both the British colonists and indigenous people to his proselytism. He returned to Maryland, where he rejoined the former Jesuits at St. Thomas Manor.

In 1793, Neale become the pastor of Old St. Joseph's and Old St. Mary's Churches in Philadelphia. Bishop Carroll also made him vicar general for Philadelphia and the northern states. During the yellow fever epidemic, Neale established the first Catholic orphanage in Philadelphia to care for the many orphaned children, and he contracted the disease.

Neale was the president of Georgetown College from 1799 to 1806, where his imposition of strict discipline caused declining student enrollment. Though he had been appointed in 1795, he was consecrated as the coadjutor bishop of Baltimore in 1800. Neale supported the restoration of the Jesuits in the United States, which occurred in 1805. He also established the Georgetown Visitation Monastery and Academy in 1799. Neale became the Archbishop of Baltimore in 1815, and was faced with several lay trustee conflicts, the most severe of which resulted in a temporary schism in Charleston, South Carolina.

Early life

Leonard Neale was born on October 15, 1746,[1] at Chandler's Hope, the Neale family estate near Port Tobacco, located in Charles County in the British Province of Maryland.[2] He was born into a prominent Maryland family; among his ancestors was Captain James Neale, one of the settlers of the Maryland Colony, who arrived in 1637 upon receiving a royal grant of 2,000 acres (810 ha) in what would become Port Tobacco.[3] Neale's parents, William Neale and Anne Neal née Brooke, had thirteen children.[4]

Two of Neale's brothers died during their studies, while four of the surviving five became Catholic priests. One of them, Charles Neale, would become a prominent Jesuit in the United States,[4] while another, Francis Neale, would also become president of Georgetown College.[5] One sister, Anne, entered the Order of Poor Clares as a nun, in Aire-sur-la-Lys, France.[6] Through his sister, Mary, Neale's nephew was William Matthews, another future president of Georgetown.[4]

Neale first attended the Bohemia Manor School, near his home.[7] The widowed Anne Neale sought to enroll her sons in a Catholic college, but Catholic educational institutions were banned in the British colony.[8] Therefore, all seven of Neale's brothers were sent to the Colleges of St Omer, Bruges, or Liège,[4] and he left for Saint-Omer, France at the age of twelve,[9] where he proved to be a good student. Deciding that he would become a Jesuit,[10] he followed the college to Bruges,[11] where he entered the Society of Jesus on September 7, 1767.[12] He then continued when the school relocated to Liège,[1] where he completed his study of philosophy and theology,[10] and was ordained a priest on June 5, 1773.[12]

Ministry

Neale then returned to Bruges in 1773 as a member of the faculty.[7] Later that year, when Pope Clement XIV promulgated a brief, titled Dominus ac Redemptor, ordering the worldwide suppression of the Society of Jesus,[13] the Jesuit college was seized by the government of the Austrian Netherlands and all the Jesuits were expelled.[7] Therefore, Neale moved with the English Jesuits to England as a secular priest. He spent his first four years in England in charge of a small congregation,[13] in Hardwick, County Durham.[14] He spent the subsequent two years first in Liège, then in Brussels, then as a temporary chaplain at the convent of the English Canonesses in Bruges.[15]

Missionary in British Guiana

Before long, Neale petitioned to be assigned as a foreign missionary, and in 1779, he left England for Demerara,[16] in British Guiana. His first task was to convert the British colonists living there. However, they rejected his attempts and barred him from building a chapel. As a result, he turned his attention to the conversion of the indigenous people.[17]

Neale found his work of proselytizing the indigenous people difficult.[16] However, on one occasion, the tribal chief, who previously resisted the efforts to convert to Christianity, implored Neale to spiritually intervene to save his dying son. Neale baptized the son, who was then restored to health, and the chief and his family converted to Christianity; others also followed.[18] Nonetheless, Neale was unsuccessful in obtaining many conversions, and the people were largely opposed to him. They too barred him from building a church. Discouraged by the resistance of the people to his efforts, and experiencing deteriorating health, Neale left the mission in January 1783, setting sail for Maryland.[19] His voyage was delayed when his ship was seized by the British Royal Navy, during the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War.[17] Neale eventually arrived in Maryland in April.[20]

Return to the United States

With his studies and ministry in Europe and South America, Neale had been absent from the United States for 25 years.[21] He rejoined his former Jesuit colleagues from Europe, including John Carroll, and was stationed at St. Thomas Manor. Neale attended the first meeting of the Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen of Maryland,[lower-alpha 1] held at White Marsh Manor in 1783,[20] and remained active in its subsequent deliberations throughout the years.[21] He was an outspoken leader of a group of former Jesuits who opposed Carroll's sale of land held by the corporation to finance the establishment of Georgetown College.[23]

Philadelphia

Neale was stationed at St. Thomas Manor until volunteering to go to Philadelphia in 1793, following the outbreak of a yellow fever epidemic in the city.[24] The disease claimed 10% of Philadelphia's population, including the pastor, Dominic Lawrence Graessel, and two assistant priests at Old St. Joseph's Church, in addition to hundreds of its parishioners.[25] Despite the precarious state of his own health, Neale became pastor of both Old St. Joseph's and Old St. Mary's Church.[26] Neale himself eventually contracted yellow fever and recovered,[27] although never completely to his former health.[28] In addition to his two pastorates, he was made vicar general to Bishop John Carroll for Philadelphia and the northern states.[7]

When the epidemic returned in 1797 and 1798,[27] Neale established the first Catholic orphanage in Philadelphia to care for the children whose parents had died of the disease.[25] Though he found it difficult to raise sufficient funds to support the new institution, the orphanage would eventually be incorporated in 1807 as St. Joseph's Orphan Asylum. Neale's tenure as pastor of St. Joseph's and St. Mary's came to an end in March 1799, and he was succeeded by Matthew Carr.[26]

President of Georgetown

In 1799,[7] Bishop John Carroll recalled Neale from Philadelphia, to replace Louis William Valentine DuBourg as president of Georgetown College in Washington, D.C.[1] He officially assumed the office on March 30, 1799.[29] In addition to his duties as president, Neale acted as a tutor at the college for several years. He was the first president to comply with the requirement set by the college's board of directors that the president live at the college.[30] Authority over the college's finances rested with the vice president, Neale's brother, Francis.[31] The financial conditions of the still-nascent college were unsteady; as a result, Old North remained unfinished, money for food was not guaranteed, and Neale slept on a folding bed in the library.[32]

Neale's overall leadership of the college was considered lacking. As his brother later would, Neale instituted strict discipline among the students, adopting a quasi-monastic regimen. He also segregated the seminary candidates from the lay students; the Catholic students were also segregated from the many non-Catholic students, who were housed off-campus. Neale's imposition of strict discipline drew the criticism of John Carroll, who believed that it was dissuading parents from sending their sons to the college, as the prevailing American spirit of liberty was unaccustomed to such strictures.[33] Nonetheless, while the overall number of enrolled students decreased, Georgetown produced a considerable number of Jesuit novices during his tenure.[32]

Neale phased out the lay faculty so that all the professors were either Jesuits, Sulpicians, secular priests, or seminarians. He also expanded the course of studies by adding philosophy, the final course in the full Jesuit curriculum.[33] This was done both to fulfill the college's earlier prospectus that claimed it would offer philosophy, and because DuBourg sought to expand St. Mary's Seminary in Baltimore to include the comprehensive education of lay students; both Neale and Carroll feared that this would draw students away from Georgetown.[34] The college began teaching philosophy in 1801, making it a full college in the view of the Jesuit curriculum.[35] Neale's tenure as president of the college came to an end in 1806, and he was succeeded by Robert Molyneux.[5]

According to one historical legend among the Jesuits and slaves of Maryland,[36] President George Washington underwent a deathbed conversion while he was attended by Neale.[37] The story holds that Neale was summoned by Washington and taken by rowboat from St. Thomas Manor to Mount Vernon.[38] There, Neale heard Washington's confession and conditionally baptized him, receiving him into the Catholic Church.[39] One Catholic historian, Martin I. J. Griffin, concluded that this legend was likely untrue,[40] and written accounts by those present at Washington's final hours make no mention of a minister of any religion being present.[41]

Georgetown Visitation Monastery and Academy

While serving in Philadelphia, Neale had become acquainted with Alice Lalor, an Irish immigrant to whom Neale became her confessor. She sought to return to Kilkenny to establish a religious community, but Neale convinced her to remain in the United States, where he would assist her in founding a community.[42] Along with two other women, they established a small school for girls. However, these two women would die of yellow fever,[30] and the school was disbanded.[1]

When Neale relocated to Georgetown, he called Lalor and two associates of hers to the city in 1799,[43] where they took up residence with a community of Poor Clares in Georgetown, so that they could discern which religious order they should enter.[44] Eventually, Neale determined that the Order of the Visitation of Holy Mary would be most suited to their mission, and in light of the growing Catholic population in the District of Columbia that sought to have a Catholic school for their daughters. Neale drew up the rules for their enclosed community.[45] Though the new community faced financial strain, Neale purchased the monastery of the Poor Clares, who were returning to Europe, and transferred ownership of it to the nuns on June 29, 1808.[1] There, they began operating a school, Georgetown Visitation Academy, which would become Georgetown Visitation Preparatory School.[43] Neale received the nuns' simple vows in 1813,[1] and would remain their spiritual director for the remainder of his life.[46]

Prelate of Baltimore

Coadjutor bishop

.jpg.webp)

John Carroll, the Bishop of Baltimore, found it difficult to minister to his very large diocese, which encompassed the entire United States. Therefore, he requested that the Vatican appoint a coadjutor bishop to assist him.[47] Dominic Lawrence Graessel was selected by the Baltimore diocesan clergy to be the coadjutor, in 1795. However, before he could be installed as coadjutor, he died.[48] Therefore, Bishop Carroll requested that the Sacred Congregation de Propaganda Fide appoint Neale as coadjutor. On March 23, 1795, the Propaganda Fide selected him and Pope Pius VI confirmed its selection on April 17.[21] Neale was also named as the Titular Bishop of Gortyna. However, due to the European political turmoil resulting from the French Revolution,[21] the bulls of appointment were twice lost before reaching Carroll; they were eventually forwarded in January 1800 by Cardinal Stefano Borgia via Venice, and reached Baltimore in the summer.[12] Neale was consecrated a bishop on December 7, 1800, at St. Peter's Pro-Cathedral in Baltimore,[49] with Bishop John Carroll serving as consecrator. With this ceremony, he became the first bishop to be consecrated inside the United States.[7] Neale continued to reside at Georgetown, where he was president.[50]

When Pope Pius VII issued a bull in 1801, at the request of Emperor Paul I of Russia, lifting the order of suppression of the Jesuits within the Russian Empire (where they had never ceased operating),[51] Neale and his brothers, Francis and Charles, were among the most ardent supporters of the American Jesuits affiliating with the Russian province so as to resume official operations in the United States. Though Carroll was initially resistant to such a precarious arrangement, he eventually consented, and he and Neale requested permission from Gabriel Gruber, the Jesuit Superior General. In 1805, the Society of Jesus was restored in the United States, and the Jesuit novitiate opened at Georgetown College.[52] With the order newly re-established, it relied on foreign support, and Carroll succeeded in recruiting several European Jesuits, such as Anthony Kohlmann, to Georgetown.[32]

Archbishop of Baltimore

When John Carroll died, Neale succeeded him as the second Archbishop of Baltimore on December 3, 1815, and he received the pallium from Pope Pius VII the following year. He ascended to the position at the age of 70, and his health had begun to deteriorate.[46] Rather than moving to Baltimore, Neale continued to reside in Georgetown, near the Visitation nuns. One of his first acts was to request that Pope Pius VII formally recognize the Visitation nuns' community. With the pope's approval, Neale officially recognized the community as the Georgetown Visitation Monastery.[53] For this, he was recognized as the founder of the institution.[7]

The most significant challenge that Neale faced during his time as archbishop was the growing phenomenon of lay trusteeism in the United States, whereby the states vested the ownership of church property and management of its affairs, including the selection of the church's priests, in a board of lay trustees elected by parishioners.[54] While facially compliant with the Catholic canon law of jus patronatus, this arrangement often resulted in the trustees defying the orders of bishops in managing the churches.[55] Neale inherited much of this conflict that arose during his predecessor's tenure.[54] His first conflicts were with boards of trustees in Philadelphia in 1796, and in Norfolk, Virginia.[56]

A much larger controversy would be found in Charleston, South Carolina, which came to be known as the Charleston Schism of 1815 to 1818. In 1815, Carroll assigned the French priest Pierre-Joseph de Clorivière as the pastor of St. Mary of the Annunciation Church, where Carroll had previously stationed him as an assistant priest. Clorivière would take the place of the interim pastor, Robert Browne, who was to return to his congregation in Augusta, Georgia.[57] The trustees of the church, which was predominantly Irish and harbored anti-French sentiment, opposed Clorivière.[55]

Browne defied Neale's order to return to Augusta, and Browne's predecessor at St. Mary's, Felix Simon Gallagher, asserted that Neale had no authority to appoint a new pastor without his assent, and that to do so would be schismatic. Neale responded by withdrawing the priestly faculties of Gallagher and Browne on February 21, 1816. However, Browne ignored Neale's order, resuming the pastorate on March 28 and dismissing Clorivière.[58] With the congregation siding with Browne, Neale placed the church under an interdict.[59] Browne then argued his case in Rome, where he obtained an order from Cardinal Lorenzo Litta, the prefect of the Propaganda Fide, allowing him to return as pastor. Neale appealed this decision to Pope Pius VII, who reversed Litta on July 6, 1817.[60]

Due to his declining health, Neale requested that the authorities in Rome appoint Jean-Louis Lefebvre de Cheverus, the Bishop of Boston, as his coadjutor to assist him, but Cheverus objected. Instead, Ambrose Maréchal was appointed on July 24, 1817, but before he could receive notification of this, Neale died on June 18, 1817; Maréchal succeeded him as archbishop.[1] He was buried in the crypt of the chapel at the Visitation Monastery.[50]

The Leonard Neale House in the Dupont Circle neighborhood of Washington, D.C. was the home of a Jesuit community from the 1960s until its merger with the Jesuit community at Gonzaga College High School in 2016.[61][62]

See also

Informational notes

- The corporation was created in 1792 in response to the suppression of the Society of Jesus. Its purpose was to preserve the property of the former Jesuits with the hope that the Society would be one day restored and the property returned under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Jesuit superior in America.[22]

References

Citations

- McNeal 1911

- Chandler's Hope: Architectural Survey File 2003, pp. 2, 15

- Warner 1994, p. 18

- Warner 1994, p. 19

- Curran 1993, p. 404

- Currier 1890, p. 53

- "Most Rev. Leonard Neale". Archdiocese of Baltimore. Archived from the original on May 23, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- Clarke 1872, pp. 117–118

- Clarke 1872, p. 118

- Clarke 1872, p. 119

- Guilday 1924, p. 2

- Corrigan 1916, p. 373

- Clarke 1872, p. 120

- Miscellanea · IV 1907, p. 248

- Guilday 1924, pp. 2–3

- Clarke 1872, p. 121

- Guilday 1924, p. 3

- Clarke 1872, pp. 121–122

- Clarke 1872, p. 122

- Clarke 1872, p. 123

- Guilday 1924, p. 4

- Curran 2012, pp. 14–16

- Curran 1993, p. 14

- Clarke 1872, p. 124

- "Old St. Joseph's In The 18th Century". Old St. Joseph's Church. Archived from the original on May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- Griffin 1882, p. 6

- Clarke 1872, p. 125

- Curran 1993, p. 53

- Shea 1891, p. 26

- Clarke 1872, p. 129

- Curran 1993, p. 65

- Curran 1993, p. 59

- Curran 1993, p. 54

- Curran 1993, p. 55

- Shea 1891, p. 29

- "Slaves Held Washington Died Baptized Catholic". Denver Catholic Register, National Edition. February 24, 1957. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- Griffin 1900, p. 123

- Griffin 1900, p. 127

- Griffin 1900, p. 128

- Griffin 1900, p. 129

- Twohig, Dorothy; Henriques, Peter; Higginbotham, Don. "George Washington and the Legacy of Character". Fathom.com. Columbia University. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012.

- Clarke 1872, p. 128

- "History of Georgetown Visitation". Georgetown Visitation Preparatory School. Archived from the original on April 30, 2020. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- Clarke 1872, p. 131

- Clarke 1872, p. 132

- Clarke 1872, p. 134

- Clarke 1872, p. 130

- "Rt. Rev. Dominic Laurence Graessel". Archdiocese of Baltimore. Archived from the original on May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- The Catholic Church in the United States of America 1914, p. 59

- Guilday 1924, p. 5

- Shea 1891, p. 516

- Curran 1993, p. 58

- Clarke 1872, p. 135

- Guilday 1924, pp. 6–7

- Guilday 1924, p. 8

- Guilday 1924, p. 7

- Furey 1887, p. 185

- Furey 1887, p. 186

- "Our History". St. Mary of the Annunciation Catholic Church. Archived from the original on October 23, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- Furey 1887, p. 187

- Reese, Thomas (March 24, 2016). "How many Jesuits does it take to change a light bulb?". National Catholic Reporter. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- LoBiondo 2017, p. 18

Bibliography

- "Chandler's Hope: Architectural Survey File" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. November 21, 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 27, 2017. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- Clarke, Richard H. (1872). "The Most Rev. Leonard Neale, D.D.". Lives of the Deceased Bishops of the Catholic Church in the United States. Vol. 1. New York: P. O'Shea. pp. 116–138. OCLC 809578529. Retrieved May 23, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- Corrigan, Owen B. (January 1916). "Chronology of the Catholic Hierarchy of the United States". The Catholic Historical Review. 1 (4): 367–389. JSTOR 25011363.

- Curran, Robert Emmett (1993). The Bicentennial History of Georgetown University: From Academy to University, 1789–1889. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-0-87840-485-8. Archived from the original on April 1, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2020 – via Google Books.

- Curran, Robert Emmett (2012). "Ambrose Maréchal, the Jesuits, and the Demise of Ecclesial Republicanism in Maryland, 1818–1838". Shaping American Catholicism: Maryland and New York, 1805–1915. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press. pp. 13–158. ISBN 978-0813219677. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- Currier, Charles Warren (1890). Carmel in America: A Centennial History of the Discalced Carmelites in the United States. Baltimore: John Murphy & Co. OCLC 558196119 – via Internet Archive.

- Furey, Francis T. (October 1887). "The Charleston, S. C., Schism of 1815–1818". The American Catholic Historical Researches. 4 (2): 184–188. JSTOR 45213255.

- Griffin, Martin I. J. (1882). History of "Old St. Joseph's". Philadelphia: I.C.B.U. Journal Print. OCLC 74848131. Retrieved May 24, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- Griffin, Martin I. J. (July 1900). "Did Washington Die A Catholic?". The American Catholic Historical Researches. 17 (3): 123–129. JSTOR 44374155.

- Guilday, Peter (1924). "Chapter 1: The Catholic Church in Virginia Under Archbishop Neale". The Catholic Church in Virginia (1815–1822). Monograph Series VIII. New York: United States Catholic Historical Society. pp. 1–27. OCLC 10721426. Archived from the original on May 23, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2020 – via Google Books.

- LoBiondo, Gasper (Winter 2017). ""Friends in the Lord:" In January, the Jesuit Community on Eye Street More Than Doubled". The Good News From 19 I Street. pp. 18–21. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2020 – via Issuu.

- McNeal, James Preston Wickham (1911). "Leonard Neale". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company. OCLC 1017058.

- Miscellanea · IV. Publications of the Catholic Record Society. Vol. 4. London: Arden Press. 1907. OCLC 866475038. Archived from the original on May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2020 – via Google Books.

- Shea, John Gilmary (1891). "Chapter IV: Rt. Rev. Leonard Neale, D.D.". Memorial of the First Century of Georgetown College, D.C.: Comprising a History of Georgetown University. Vol. 3. Washington, D.C.: P. F. Collier. pp. 26–32. OCLC 960066298. Archived from the original on April 1, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2020 – via Google Books.

- The Catholic Church in the United States of America: Undertaken to Celebrate the Golden Jubilee of His Holiness, Pope Pius X. Vol. 3. New York: Catholic Editing Company. 1914. OCLC 972339830. Retrieved May 25, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- Warner, William W. (1994). At Peace with All Their Neighbors: Catholics and Catholicism in the National Capital, 1787–1860. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-1589012431. Retrieved May 23, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

Further reading

- Hennesey, James (June 1972). "First American Foreign Missionary: Leonard Neale in Guyana". Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. 83 (2): 82–86. JSTOR 44210793.

- "Memoir of the Most Rev. Archbishop Neale". The Metropolitan. Vol. 5, no. 1. February 1857. pp. 18–25. Retrieved May 26, 2020 – via Internet Archive.