Leprechaun

A leprechaun (Irish: lucharachán/leipreachán/luchorpán) is a diminutive supernatural being in Irish folklore, classed by some as a type of solitary fairy. They are usually depicted as little bearded men, wearing a coat and hat, who partake in mischief. In later times, they have been depicted as shoe-makers who have a hidden pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

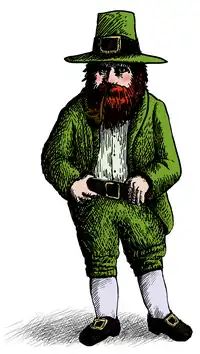

A modern depiction of a leprechaun of the type popularised in the 20th century | |

| Grouping | Legendary creature Pixie Sprite Fairy Aos Sí |

|---|---|

| First attested | In folklore |

| Country | Ireland |

| Details | Found in a moor, forest, cave, garden |

Leprechaun-like creatures rarely appear in Irish mythology and only became prominent in later folklore.

Etymology

The Anglo-Irish (Hiberno-English) word leprechaun is descended from Old Irish luchorpán or lupracán,[1] via various (Middle Irish) forms such as luchrapán, lupraccán,[2][3] (or var. luchrupán).[lower-alpha 1]

Modern forms

The current spelling leipreachán is used throughout Ireland, but there are numerous regional variants.[6]

John O'Donovan's supplement to O'Reilly's Irish-English Dictionary defines lugharcán, lugracán, lupracán as "a sprite, a pigmy; a fairy of a diminutive size, who always carries a purse containing a shilling".[7][8][lower-alpha 2]

The Irish term leithbrágan in O'Reilly's Dictionary[10] has also been recognized as an alternative spelling.[8]

Other variant spellings in English have included lubrican, leprehaun, and lepreehawn. Some modern Irish books use the spelling lioprachán.[11] The first recorded instance of the word in the English language was in Dekker's comedy The Honest Whore, Part 2 (1604): "As for your Irish lubrican, that spirit / Whom by preposterous charms thy lust hath rais'd / In a wrong circle."[11]

Meanings

The word may have been coined as a compound of the roots lú or laghu (from Greek: ἐ-λαχύ "small") and corp (from Latin: corpus "body"), or so it had been suggested by Whitley Stokes.[12][lower-alpha 3] Research published in 2019 suggests the word derives from the Luperci and associated Roman festival of Lupercalia.[14][15][16]

Folk etymology derives the word from leith (half) and bróg (brogue), because of the frequent portrayal of the leprechaun as working on a single shoe, as evident in the alternative spelling leithbrágan.[10][8][lower-alpha 4]

Early attestations

The earliest known reference to the leprechaun appears in the medieval tale known as the Echtra Fergus mac Léti ('Adventure of Fergus son of Léti').[17] The text contains an episode in which Fergus mac Léti, King of Ulster, falls asleep on the beach and wakes to find himself being dragged into the sea by three lúchorpáin. He captures his abductors, who grant him three wishes in exchange for release.[18][19]

Folklore

The leprechaun is said to be a solitary creature, whose principal occupation is making and cobbling shoes, and who enjoys practical jokes.[20] In McAnally's 1888 account, the Leprechaun was not a professional cobbler, but was frequently seen mending his own shoes, as "he runs about so much he wears them out" with great frequency. This is, he claims, the perfect opportunity for a human being to capture the Leprechaun, refusing to release him until the Leprechaun gives his captor supernatural wealth.[21]

Classification

The leprechaun has been classed as a "solitary fairy" by the writer and amateur folklorist William Butler Yeats.[lower-alpha 5][23] Yeats was part of the revivalist literary movement greatly influential in "calling attention to the leprechaun" in the late 19th century.[24] This classification by Yeats is derived from D. R. McAnally (Irish Wonders, 1888) derived in turn from John O'Hanlon (1870).[25]

It is stressed that the leprechaun, though some may call it fairy, is clearly to be distinguished from the Aos Sí (or the 'good people') of the fairy mounds (sidhe) and raths.[27][28][29][lower-alpha 6] Leprachaun being solitary is one distinguishing characteristic,[31][32] but additionally, the leprachaun is thought to only engage in pranks on the level of mischief, and requiring special caution, but in contrast, the Aos Sí may carry out deeds more menacing to humans, e.g., the spiriting away of children.[27]

This identification of leprechaun as a fairy has been consigned to popular notion by modern folklorist Diarmuid Ó Giolláin. Ó Giolláin observes that the dwarf of Teutonic and other traditions as well as the household familiar are more amenable to comparison.[6]

According to William Butler Yeats, the great wealth of these fairies comes from the "treasure-crocks, buried of old in war-time", which they have uncovered and appropriated.[33] According to David Russell McAnally the leprechaun is the son of an "evil spirit" and a "degenerate fairy" and is "not wholly good nor wholly evil".[34]

Appearance

The leprechaun originally had a different appearance depending on where in Ireland he was found.[35] Before the 20th century, it was generally held that the leprechaun wore red, not green. Samuel Lover, writing in 1831, describes the leprechaun as,

... quite a beau in his dress, notwithstanding, for he wears a red square-cut coat, richly laced with gold, and inexpressible of the same, cocked hat, shoes and buckles.[36]

According to Yeats, the solitary fairies, like the leprechaun, wear red jackets, whereas the "trooping fairies" wear green. The leprechaun's jacket has seven rows of buttons with seven buttons to each row. On the western coast, he writes, the red jacket is covered by a frieze one, and in Ulster the creature wears a cocked hat, and when he is up to anything unusually mischievous, he leaps onto a wall and spins, balancing himself on the point of the hat with his heels in the air.[37]

According to McAnally the universal leprechaun is described as

He is about three feet high, and is dressed in a little red jacket or roundabout, with red breeches buckled at the knee, gray or black stockings, and a hat, cocked in the style of a century ago, over a little, old, withered face. Round his neck is an Elizabethan ruff, and frills of lace are at his wrists. On the wild west coast, where the Atlantic winds bring almost constant rains, he dispenses with ruff and frills and wears a frieze overcoat over his pretty red suit, so that, unless on the lookout for the cocked hat, ye might pass a Leprechawn on the road and never know it's himself that's in it at all.

This dress varied by region. In McAnally's account there were differences between leprechauns or Logherymans from different regions:[38]

- The Northern Leprechaun or Logheryman wore a "military red coat and white breeches, with a broad-brimmed, high, pointed hat, on which he would sometimes stand upside down".

- The Lurigadawne of Tipperary wore an "antique slashed jacket of red, with peaks all round and a jockey cap, also sporting a sword, which he uses as a magic wand".

- The Luricawne of Kerry was a "fat, pursy little fellow whose jolly round face rivals in redness the cut-a-way jacket he wears, that always has seven rows of seven buttons in each row".

- The Cluricawne of Monaghan wore "a swallow-tailed evening coat of red with green vest, white breeches, black stockings," shiny shoes, and a "long cone hat without a brim," sometimes used as a weapon.

In a poem entitled The Lepracaun; or, Fairy Shoemaker, 18th century Irish poet William Allingham describes the appearance of the leprechaun as:

...A wrinkled, wizen'd, and bearded Elf,

Spectacles stuck on his pointed nose, Silver buckles to his hose,

Leather apron — shoe in his lap...[39]

The modern image of the leprechaun sitting on a toadstool, having a red beard and green hat, etc. is clearly a more modern invention, or borrowed from other strands of European folklore.[40] The most likely explanation for the modern day Leprechaun appearance is that green is a traditional national Irish color dating back as far as 1642.[41] The hat might be derived from the style of outdated fashion still common in Ireland in the 19th century. This style of fashion was commonly worn by Irish immigrants to the United States, since some Elizabethan era clothes were still common in Ireland in the 19th century long after they were out of fashion, as depicted by the Stage Irish. The buckle shoes and other garments also have their origin in the Elizabethan period in Ireland.

Similar creatures

The leprechaun is similar to the clurichaun and the far darrig in that he is a solitary creature. Some writers even go as far as to substitute these second two less well-known spirits for the leprechaun in stories or tales to reach a wider audience. The clurichaun is considered by some to be merely a leprechaun on a drinking spree.[42]

In politics

In the politics of the Republic of Ireland, leprechauns have been used to refer to the twee aspects of the tourism field in Ireland.[43][44] This can be seen from this example of John A. Costello addressing the Oireachtas in 1963—

For many years, we were afflicted with the miserable trivialities of our tourist advertising. Sometimes it descended to the lowest depths, to the caubeen and the shillelagh, not to speak of the leprechaun.[44]

Popular culture

Films, television cartoons and advertising have popularised a specific image of leprechauns which bears little resemblance to anything found in the cycles of Irish folklore. It has been argued that the popularised image of a leprechaun is little more than a series of stereotypes based on derogatory 19th-century caricatures.[45][46]

Many Celtic Music groups have used the term Leprechaun LeperKhanz as part of their naming convention or as an album title. Even popular forms of American music have used the mythological character, including heavy metal, celtic metal, punk rock and jazz.

- Possibly the most notable of all is Lucky the mascot of Lucky Charms cereal, made by General Mills.

- The Notre Dame Leprechaun is the official mascot of the Fighting Irish sports teams at the University of Notre Dame

- Boston Celtics logo features the mascot of the team, Lucky the Leprechaun

- Professional wrestler Dylan Mark Postl competed and appeared as Hornswoggle, a leprechaun who lived under the ring, for the majority of his WWE tenure.

- The 1993 American horror slasher-film Leprechaun and its sequels feature a killer leprechaun portrayed by Warwick Davis.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman coined the term "leprechaun economics" to describe distorted or unsound economic data, which he first used in a tweet on 12 July 2016 in response to the publication by the Irish Central Statistics Office (CSO) that Irish GDP had grown by 26.3%, and Irish GNP had grown by 18.7%, in the 2015 Irish national accounts. The growth was subsequently shown to be due to Apple restructuring its double Irish tax scheme which the EU Commission had fined €13bn in 2004–2014 Irish unpaid taxes, the largest corporate tax fine in history. The term has been used many times since.

In America, Leprechauns are often associated with St. Patrick's Day along with the color green and shamrocks.

Darby O'Gill

The Disney film Darby O'Gill and the Little People (1959)—based on Herminie Templeton Kavanagh's Darby O'Gill books—which features a leprechaun king, is a work in which Fergus mac Léti was "featured parenthetically".[47] In the film, the captured leprechaun king grants three wishes, like Fergus in the saga.

While the film project was in development, Walt Disney was in contact with, and consulting Séamus Delargy and the Irish Folklore Commission, but never asked for leprechaun material, even though a large folkloric repository on such subject was housed by the commission.[48][lower-alpha 7]

See also

Explanatory notes

- Another (intermediary) form is luchrupán, listed by Ernst Windisch,[4] which is identified as Middle Irish by the OED[5] Windisch does not comment on this being the root to English "leprechaun"

- Patrick Dinneen (1927) defines as "a pigmy, a sprite, or leprechaun".[9]

- The root corp, which was borrowed from the Latin corpus, attests to the early influence of Ecclesiastical Latin on the Irish language.[13]

- Cf. Yeats (1888), p. 80.

- Or Yeats of "armchair folklore", to use a moniker from Kinahan's paper.[22]

- The anthologist Charles Squire makes the further considers the Irish fairy to be part of the tradition of the Tuatha Dé Danann, whereas the leprachaun, puca (and the English/Scottish household spirits) have a different origin.[30]

- The Commission would have preferred the project be not about leprechauns, and Delargy was clearly of this sentiment.[49] The commission's archivist Bríd Mahon also recalls suggesting as alternatives the heroic sagas like the Táin or the novel The Well at the World's End, to no avail.Tracy (2010), p. 48

References

Citations

- "Leprechaun: a new etymology". bill.celt.dias.ie. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- Binchy (1952), p. 41n2.

- Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí (1991). Myth, Legend & Romance: An encyclopaedia of the Irish folk tradition. New York: Prentice Hall. p. 270. ISBN 9780132759595.

- Windisch, Ernst (1880). Irische Texte mit Wörterbuch. Whitley Stokes. Leipzig: S. Hirzel. p. 839.

- Windisch cited as "Cf. Windisch Gloss." in The Oxford English Dictionary s. v. "leprechaun", 2nd ed., 1989, OED Online "leprechaun", Oxford University Press, (subscription needed) 16 July 2009.

- Ó Giolláin (1984), p. 75.

- O'Donovan's supplement in O'Reilly, Edward (1864) An Irish-English Dictionary, s.v. "lugharcán, lugracán, lupracán".

- O'Donovan in O'Reilly (1817)Irish Dict. Suppl., cited in The Oxford English Dictionary s.v. "leprechaun", 2nd ed, 1989, OED Online, Oxford University Press, (subscription needed) 16 July 2009.

- Patrick S. Dinneen, Foclóir Gaedhilge agus Béarla (Dublin: Irish Texts Society, 1927).

- O'Reilly, Edward (1864) An Irish-English Dictionary, s.v. "leithbrágan".

- "leprechaun" The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed., 1989, OED Online, Oxford University Press, (subscription needed) 16 July 2009

- Stokes, Whitley (1870). "Mythological Notes". Revue Celtique. 16 (Contributions in Memory of Osborn Bergin): 256–257.

- "leprechaun" The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed., 2004, Dictionary.com, Houghton Mifflin Company, 16 July 2009.

- Leprechaun 'is not a native Irish word' new dictionary reveals, BBC, 5 September 2019.

- Lost Irish words rediscovered, including the word for ‘oozes pus', Queen's University Belfast research for the Dictionary of the Irish Language reported by Cambridge University.

- lupracán, luchorpán on the Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language (accessed 6 September 2019)

- Koch, p. 1059; 1200.

- Koch, p. 1200.

- Binchy (1952) ed. & trans., "The Saga of Fergus mac Léti"

- Winberry (1976), p. 63.

- McAnally, Irish Wonders, 143.

- Kinahan (1983).

- Yeats (1888), p. 80.

- Winberry (1976), p. 72.

- Kinahan (1983), p. 257 and note 5.

- Harvey, Clodagh Brennan (1987). "The Supernatural in Immigrant and Ethnic Folklore: Conflict or Coexistence?". Folklore and Mythology Studies. 10: 26.

- Winberry (1976), p. 63: "The leprechaun is unique among Irish fairies and should not be confused with the Aes Sidhe, the 'good people', who populate the fairy mounds and raths, steal children, beguile humans, and perform other malicious pranks. "; also partially quoted by Harvey.[26]

- O'Hanlon (1870), p. 237: "The Luricane, Lurigadawne, or Leprechawn, is an elf essentially to be discriminated from the wandering sighes, or trooping fairies."

- McAnally (1888), p. 93: "Unlike Leprechawns, the good people are not solitary, but quite sociable"; quoted by Kinahan (1983), p. 257.

- Squire, Charles (1905). The Mythology of the British Islands: An Introduction to Celtic Myth, Legend, Poetry, and Romance. London: Blackie and Son. pp. 247–248, 393, 403.

- O'Hanlon (1870), p. 237.

- McAnally (1888), p. 93.

- Yeats (1888), p. 80.

- McAnally, Irish Wonders, 140.

- "Little Guy Style". Archived from the original on 29 July 2007. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- From Legends and Stories of Ireland

- From Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry.

- McAnally, Irish Wonders, 140–142.

- William Allingham – The Leprechaun Archived 1 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- A dictionary of Celtic mythology

- Andries Burgers (21 May 2006). "Ireland: Green Flag". Flags of the World. Citing G. A. Hayes-McCoy, A History of Irish Flags from earliest times (1979)

- Yeats, Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, 321.

- "Dáil Éireann – Volume 495 – 20 October, 1998 – Tourist Traffic Bill, 1998: Second Stage". Archived from the original on 15 May 2006.

- "Dáil Éireann – Volume 206 – 11 December, 1963 Committee on Finance. – Vote 13—An Chomhairle Ealaoín". Archived from the original on 12 March 2007.

- Venable, Shannon (2011). Gold: A Cultural Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 196–197.

- Diane Negra, ed. (22 February 2006). The Irish in Us: Irishness, Performativity, and Popular Culture. Duke University Press. p. . ISBN 0-8223-3740-1.

- O Croinin, Daibhi (2016). Early Medieval Ireland 400-1200 (2nd revised ed.). New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 96. ISBN 9781317192701.

- Tracy (2010), p. 35

- Tracy (2010), p. 50.

Bibliography

- Binchy, D. A. (1952). "The Saga of Fergus Mac Léti". Ériu. 16 (Contributions in Memory of Osborn Bergin): 33–48. JSTOR 30007384.; online text via UCD.

- Briggs, Katharine. An Encyclopedia of Fairies: Hobgoblins, Brownies, Bogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures. New York: Pantheon, 1978.

- Croker, T. C. Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland. London: William Tegg, 1862.

- Hyde, Douglas. Beside The Fire. London: David Nutt, 1910.

- Kane, W. F. de Vismes (31 March 1917). "Notes on Irish Folklore (Continued)". Folklore. 28 (1): 87–94. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1917.9718960. ISSN 0015-587X. JSTOR 1255221.

- Keightley, T. The Fairy Mythology: Illustrative of the Romance and Superstition of Various Countries. London: H. G. Bohn, 1870.

- Kinahan, F. (1983), "Armchair Folklore: Yeats and the Textual Sources of "Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry"", Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Section C: Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature, 83C: 255–267, JSTOR 25506103

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1851094407.

- Lover, S. Legends and Stories of Ireland. London: Baldwin and Cradock, 1831.

- O'Hanlon, John (1870), "XVII: The Solitary Fairies", Irish folk lore: traditions and superstitions of the country, pp. 237–241

- Ó Giolláin, Diarmuid (1984). "The Leipreachán and Fairies, Dwarfs and the Household Familiar: A Comparative Study". Béaloideas. 52: 75–150. doi:10.2307/20522237. JSTOR 20522237.

- McAnally, David Russell (1888). Irish Wonders: The Ghosts, Giants, Pookas, Demons, Leprechawns, Banshees, Fairies, Witches, Widows, Old Maids, and Other Marvels of the Emerald Isle. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin.

- Negra, D. [ed.]. The Irish in Us: Irishness, Performativity and Popular Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-8223-8784-8.

- Tracy, Tony (2010). "When Disney Met Delargy: 'Darby O'Gill' and the Irish Folklore Commission". Béaloideas. 78: 44–60. JSTOR 41412207.

- Winberry, John J. (1976). "The Elusive Elf: Some Thoughts on the Nature and Origin of the Irish Leprechaun". Folklore. 87 (1): 63–75. ISSN 0015-587X. JSTOR 1259500.

- Wilde, Jane. [Speranza, pseud.]. Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland. London : Ward and Downey, 1887.

- Yeats, William Butler (1888), "The Legend of Knockgrafton", Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, London: W. Scott

External links

Works related to Leprechaun at Wikisource

Works related to Leprechaun at Wikisource