Leptoceratops

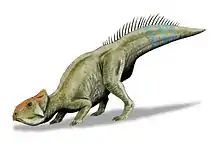

Leptoceratops (meaning 'Thin-horned face' and derived from Greek lepto-/λεπτο- meaning 'small', 'insignificant', 'slender', 'meagre' or 'lean', kerat-/κερατ- meaning 'horn' and -ops/ωψ meaning face),[1] is a genus of leptoceratopsid ceratopsian dinosaurs from the late Cretaceous Period (late Maastrichtian age, 68.8-66 Ma ago[2]) of what is now Western North America. Their skulls have been found in Alberta, Canada and Wyoming.[3][4]

| Leptoceratops Temporal range: Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian), | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossils at the Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Suborder: | †Ceratopsia |

| Family: | †Leptoceratopsidae |

| Genus: | †Leptoceratops Brown, 1914 |

| Species: | †L. gracilis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Leptoceratops gracilis Brown, 1914 | |

Description

Leptoceratops could probably stand and run on their hind legs: analysis of forelimb function indicates that even though they could not pronate their hands, they could walk on four legs.[5] Paul proposed that Leptoceratops was around 2 m (6.6 ft) long and could have weighed 100 kg (220 lb),[6] but Tereschenko proposed a maximum length of 3–4 m (9.8–13.1 ft).[7]

Discovery and species

The first small ceratopsian named Leptoceratops was discovered in 1910 by Barnum Brown in the Red Deer Valley in Alberta, Canada. He described it four years later.[8] The first specimen had a part of its skull missing, but there were later well-preserved finds by C. M. Sternberg in 1947, including one complete fossil. Later material was found in 1978 in the Bighorn Basin of northern Wyoming.[9]

The type species is Leptoceratops gracilis. In 1942, material collected in Montana was named Leptoceratops cerorhynchos, but this was later renamed Montanoceratops.[10]

Classification

Leptoceratops belonged to the Ceratopsia, a group of herbivorous dinosaurs with parrot-like beaks that thrived in North America and Asia during the Cretaceous Period. Although traditionally allied with the Protoceratopsidae, it is now placed in its own family, Leptoceratopsidae, along with dinosaurs such as Udanoceratops and Prenoceratops. The relationships of Leptoceratops to ceratopsids are not entirely clear. Although most studies suggest that they lie outside the protoceratopsids and ceratopsids, some studies suggest that they may be allied with Ceratopsidae. The absence of premaxillary teeth is one feature that supports this arrangement.[11][12][13][14]

Paleobiology

Behavior

In 2019, fossils from the Hell Creek Formation found three fossil bone beds which revealed that not only was Leptoceratops a social animal, but also raised its young in burrows.[15]

Diet

Leptoceratops, like other ceratopsians, would have been a herbivore. The jaws were relatively short and deep, and the jaw muscles would have inserted over the large parietosquamosal frill, giving Leptoceratops a powerful bite.[16] The teeth are unusual in that the dentary teeth have dual wear facets, with a vertical wear facet where the maxillary teeth sheared past the crown, and a horizontal wear facet where the maxillary teeth crushed against the dentary teeth.[17] This shows that Leptoceratops chewed with a combination of shearing and crushing. Between the shearing/crushing action of the teeth and the powerful jaws, Leptoceratops was probably able to chew extremely tough plant matter.[18] Given its small size and quadrupedal stance, Leptoceratops would have been a low feeder.[19] Flowering plants, also known as angiosperms, were the most diverse plants of the day, although ferns, cycads and conifers may still have been more common in terms of numbers.[20][21] A 2016 study revealed that Leptoceratops was able to chew its food much like several groups of mammals, which meant that it had a diet that consisted of tough, fibrous plant material.[22][23]

See also

References

- B. Brown. 1914. Leptoceratops, a new genus of Ceratopsia from the Edmonton Cretaceous of Alberta. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 33(36):567-580

- Liddell, Henry George and Robert Scott (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged ed.). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages (PDF).

- Ostrom, John H. (May 1978). "Leptoceratops gracilis from the "Lance" Formation of Wyoming". Journal of Paleontology. SEPM Society for Sedimentary Geology. 52 (3): 697–704. JSTOR 1303974. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- Lyson, Tyler R.; Longrich, Nicholas R. (2010-10-13). "Spatial niche partitioning in dinosaurs from the latest cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of North America". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1709): 1158–1164. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1444. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 3049066. PMID 20943689.

- Senter, P. (2007). "Analysis of forelimb function in basal ceratopsians". Journal of Zoology. 273 (3): 305–314. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00329.x.

- Paul, G. S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs (2nd ed.). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 280. ISBN 9780691167664.

- Tereschhenko, V. S. (2008). "Adaptive Features of Protoceratopsids (Ornithischia: Neoceratopsia)". Paleontological Journal. 42 (3): 273–286. doi:10.1134/S003103010803009X. S2CID 84366476.

- Dingus, Lowell (2012). Barnum Brown : the man who discovered Tyrannosaurus rex. Berkeley, Calif. ISBN 978-0-520-27261-3. OCLC 861963334.

- Ostrom, John H. (1978). "Leptoceratops gracilis from the "Lance" Formation of Wyoming". Journal of Paleontology. 52 (3): 697–704. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1303974.

- Brown, Barnum; Schlaikjer, Erich Maren (1942). "The skeleton of Leptoceratops with the description of a new species. American Museum novitates ; no. 1169". hdl:2246/2270.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Ott, Christopher J., "Cranial Anatomy and Biogeography of the First Leptoceratops gracilis (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) Specimens from the Hell Creek Formation, Southeast Montana", Horns and Beaks, Indiana University Press, pp. 213–234, doi:10.2307/j.ctt1zxz1md.16, retrieved 2022-07-30

- Auteur., Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium (2007 : Drumheller, Alta.). (2010). New perspectives on horned dinosaurs the Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35358-0. OCLC 758756959.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "22. Basal Ceratopsia", The Dinosauria, Second Edition, University of California Press, pp. 478–493, 2019-12-31, doi:10.1525/9780520941434-028, ISBN 9780520941434, S2CID 241167251, retrieved 2022-07-30

- Campione, Nicolas E.; Holmes, Robert (2006-12-11). "The anatomy and homologies of the ceratopsid syncervical". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (4): 1014–1017. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[1014:taahot]2.0.co;2. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 86242702.

- "Cret&Beyond-abstracts08-Fowler et al". Dickinson Museum Center. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- Kyo, Tanoue (2008-01-01). Comparative anatomy and the masticatory system of basal Ceratopsia (Ornithischia, Dinosauria). ScholarlyCommons. OCLC 857236758.

- Tanoue, Kyo; Grandstaff, Barbara S.; You, Hai-Lu; Dodson, Peter (September 2009). "Jaw Mechanics in Basal Ceratopsia (Ornithischia, Dinosauria)". The Anatomical Record: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology. 292 (9): 1352–1369. doi:10.1002/ar.20979. ISSN 1932-8486. PMID 19711460. S2CID 34736189.

- Ostrom, John H. (September 1966). "Functional Morphology and Evolution of the Ceratopsian Dinosaurs". Evolution. 20 (3): 290–308. doi:10.2307/2406631. ISSN 0014-3820. JSTOR 2406631. PMID 28562975.

- Paul, Gregory S.; Christiansen, Per (2000). <0450:fpindi>2.0.co;2 "Forelimb posture in neoceratopsian dinosaurs: implications for gait and locomotion". Paleobiology. 26 (3): 450–465. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0450:fpindi>2.0.co;2. ISSN 0094-8373. S2CID 85280946.

- "Mammal-like mastication for the dinosaur Leptoceratops". phys.org. Retrieved 2021-06-27.

- Lehman, Thomas M. (1987-01-01). "Late Maastrichtian paleoenvironments and dinosaur biogeography in the western interior of North America". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 60: 189–217. Bibcode:1987PPP....60..189L. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(87)90032-0. ISSN 0031-0182.

- Varriale, Frank (2016). "Dental microwear reveals mammal-like chewing in the neoceratopsian dinosaur Leptoceratops gracilis". PeerJ. 4: e2132. doi:10.7717/peerj.2132. PMC 4941762. PMID 27441111.

- Maiorino, Leonardo; Farke, Andrew A.; Kotsakis, Tassos; Raia, Pasquale; Piras, Paolo (2018-04-01). "Who is the most stressed? Morphological disparity and mechanical behavior of the feeding apparatus of ceratopsian dinosaurs (Ornithischia, Marginocephalia)". Cretaceous Research. 84: 483–500. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2017.11.012. ISSN 0195-6671.

Sources

- Dodson, P. (1996). The Horned Dinosaurs. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. xiv-346. ISBN 9780691028828.

Media related to Leptoceratops at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Leptoceratops at Wikimedia Commons

.png.webp)