Liber Vagatorum

Liber Vagatorum (Latin for 'Book of Vagabonds'), also known as The Book of Vagabonds and Beggars with a Vocabulary of Their Language in English,[a] is an anonymously written book first printed in Pforzheim, southwestern Germany, probably either in 1509 or 1510. Its Latin title aside, the book was entirely written in German, thereby appealed to a broader audience rather than the learned class of the era. A well-known hypothesis regarding its authorship is that Matthias Hütlin, the Spitalmeister (lit. 'hospital master') of Pforzheim, was the author; however, this theory remains contested.

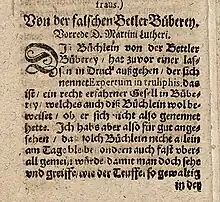

.jpg.webp) Title page of a 1510 edition; the image of a travelling beggar and his family was shared with little to no alteration by most of its earliest editions.[1] | |

| Editor | Martin Luther (1528 edition) |

|---|---|

| Translator | John Camden Hotten |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Subject | |

Publication date | c. 1509/1510[2][3] |

Published in English | 1860 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 64 (English edition) |

| OCLC | 3080033 |

| LC Class | PF5995 .L88 (1528 edition) HV4485 .L6 (English edition) |

Original text | Liber Vagatorum at Center for Retrospective Digitization |

| Translation | Liber Vagatorum at Project Gutenberg |

The book became a bestseller soon after the initial print and was reprinted many times over under different titles throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. Martin Luther, the seminal figure in the Protestant Reformation, edited a few of its editions beginning from 1528 and wrote a preface for them, which was in part a polemic against the Jews, wandering beggars, and their likes, and warned the reader not to give them alms as he believed that it was to forsake the truly poor. The book's main text does not mention the Jews, but features a catalogue of character types of beggars and their alleged techniques of deceit, and a list of more than 250 words in a cant known as Rotwelsch.

Contents

Liber Vagatorum is organised in three parts.[4] The first part comprises twenty-eight chapters that describe the "secrets" of various types of beggars; one of the types is Dützbetterin—women who claim that they have given birth to a toad, a story first documented in 1509.[5][b] The second part instructs the reader on how to avoid their traps and trickery.[4] The third part is a glossary of Rotwelsch words.[4]

Most of the earliest editions were adorned on the title page with a woodcut of a beggar leading his wife and child on their journey on foot.[1] A woodcut of a fool on horseback holding a hand mirror—created by Hans Dorn, a printer who was active in Brunswick—was used as the title illustration of a later edition.[6]

Sources and authorship

According to philologist Friedrich Kluge, Liber Vagatorum was partly based on the text Basler Rathsmandat wider die Gilen und Lamen (transl. 'Basel Council's Mandate against the Gilen and Lamen') published around 1450, which had a short list of Rotwelsch words.[7] Since the three parts of Liber Vagatorum are not coordinated well—for example, the glossary in the third part does not list some of the Rotwelsch words used in the first—Kluge concluded that the author likely had combined three different sources.[7] John Camden Hotten, who translated Liber Vagatorum into English in 1860, stated that it had been compiled from Johannes Knebel's reports of trials held in Basel, Switzerland, in 1475, when "a great number of vagabonds, strollers, blind men, and mendicants of all orders were arrested and examined".[8] These trials were later described in an 18th-century manuscript of historian Hieronymus Wilhelm Ebner von Eschenbach, which was printed in Johann Heumann von Teutschenbrunn's 1749 work Heumanni Exercitationes iuris universi, Volume One, Chapter XIII "Observatio de lingua occulta (transl. 'An observation of a secret language')"; Knebel's account is nearly identical with Ebner's, differing only in style and dialect.[8]

A well-known hypothesis regarding the anonymous author is that Matthias Hütlin, the Spitalmeister (lit. 'hospital master') of Pforzheim, authored Liber Vagatorum.[5] Hütlin belonged to the Order of the Holy Ghost, a Roman Catholic religious order devoted to the care of the ill, the poor and the orphaned; the order ran hospitals throughout Europe. He was initially provisor hospitalis (lit. 'hospital provider') and, at the suggestion of Christopher I, Margrave of Baden, was elected Spitalmeister of Pforzheim by the general chapter of the order in Strasbourg in 1500.[9]

Publication history

Liber Vagatorum was, despite its Latin title, entirely written in German—thereby appealed to a broader audience rather than the learned class of the era.[4] The four earliest editions of the book were published probably either in 1509 or 1510; the first among them was printed in Pforzheim and in High German.[2] The book was met with immediate popularity, getting at least 14 more editions printed in 1511.[10] Some of them were in Low German or Low Rhenish,[3] and one had its glossary section expanded to list 280 words.[10]

About 20 more editions were published in the remainder of the 16th century and some of them had altogether different titles.[10] Beginning from 1528, a few editions titled Von der falschen Betler Büberey (transl. 'On the Deceitful Deeds of Beggars') were edited by Martin Luther, the seminal figure in the Protestant Reformation, who rewrote some of the book's passages and authored an admonitory preface.[1][10] Those who saw only the 1528 or a later edition with his preface sometimes mistakenly ascribed the book's authorship to him.[5] Luther, in his preface, lamented that he had suffered at the hands of wandering beggars and their likes, whose alleged deceit he claimed was a sign of the devil's rule over the world. He warned the reader not to give them alms as it was, in his view, to forsake the truly poor, and declared that the Jews had contributed Hebrew words as a main basis of Rotwelsch.[5] Hotten partially agreed to this linguistic opinion, saying "the Hebrew appears to be a principal element. Occasionally a term from a neighbouring country, or from a dead language may be observed."[11] English historian Clifford Edmund Bosworth surmised that the Hebrew words had entered Rotwelsch via Yiddish.[12]

From around 1540, some editions were titled inaccurately Die Rotwelsch Grammatic (lit. 'The Rotwelsch Grammar').[10] A 1580 reprint of Von der falschen Betler Büberey was titled Ein Büchlein von den Bettlern genant Expertus in truphis (lit. 'A Little Book about Beggars, or, Expert in Frauds').[10] Around six more editions were printed in the 17th century and at least two more in the 18th century.[10]

Notes

a. ^ The title of the first English translation (1860) by John Camden Hotten

b. ^ The book's earliest known edition bears the typeface of Thomas Anshelm, whose printing work apparently ended in 1511.[5] These clues narrow the date of the first edition.[5]

References

Citations

- Hotten 1860, p. xvii.

- Considine 2017, p. 36.

- Bosworth 1976, p. 8.

- Rosenfeld 1988, p. 100.

- Rosenfeld 1988, p. 99.

- Hill-Zenk 2010, p. 331

- Kluge 1901, p. 35.

- Hotten 1860, p. xiii.

- Achnitz 2015, p. 1687.

- Considine 2017, p. 37.

- Hotten 1860, p. xxxvii.

- Bosworth 1976, p. 9.

Works cited

- Achnitz, Wolfgang, ed. (2015). "Hütlin". Deutsches Literatur-Lexikon: Das Mittelalter – Autoren und Werke nach Themenkreisen und Gattungen [German Literature Encyclopaedia: The Middle Ages – Authors and Works by Subject and Genre] (in German). Vol. 7. Das wissensvermittelnde Schrifttum im 15. Jahrhundert [The literature conveying knowledge in the 15th century]. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110367454. ISBN 9783110367454.

- Amslinger, Julia; Fromholzer, Franz; Wesche, Jörg, eds. (2019). Lose Leute: Figuren, Schauplätze und Künste des Vaganten in der Frühen Neuzeit [Loose People: Characters, Settings, and Arts of the Vagrant in the Early Modern Period] (in German). Wilhelm Fink Verlag. ISBN 9783770561728. Retrieved September 9, 2023 – via Brill.com.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1976). "Chapter 1. Vagabonds and Beggars in Early Islam". Mediaeval Islamic Underworld Volume 1: The Banū Sāsān in Arabic Society and Literature. Brill Publishers. ISBN 9789004043923. Retrieved November 13, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- Camporesi, Piero, ed. (1973). Il libro dei vagabondi. Lo «Speculum cerretanorum» di Teseo Pini, «Il vagabondo» di Rafaele Frianoro e altri testi di «furfanteria» [The Book of Vagabonds. Teseo Pini's Speculum cerretanorum, Rafaele Frianoro's The Vagabond, and other texts of "furfanteria"]. Nuova universale Einaudi (in Italian). Vol. 145. Torino: Giulio Einaudi. ISBN 9788806362690. Retrieved September 9, 2023 – via Google Books.

- Considine, John P. (2017). "Chapter 5. first curiosity-driven wordlists: Rotwelsch". Small Dictionaries and Curiosity: Lexicography and Fieldwork in Post-medieval Europe. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198785019.001.0001. ISBN 9780198785019.

- Geremek, Bronisław (1999) [1980]. Les fils de Caïn. L'image des pauvres et des vagabonds dans la littérature européenne du XVe au XVIIe siècle [The Sons of Cain. The image of the poor and vagrants in European literature from the 15th to 17th century]. Collection Champs (in French). Vol. 387. Translated by Arnold-Moricet, Joanna; Dubroeucq, Wieslawa; Maliszewska, Malgorzata; et al. Groupe Flammarion. ISBN 9782080655066. Retrieved September 9, 2023 – via Google Books.

- Hill-Zenk, Anja (2010). "Der Drucker Johannes Dorn in Braunschweig" [The Printer Johannes Dorn in Braunschweig]. Der englische Eulenspiegel: Die Eulenspiegel-Rezeption als Beispiel des englisch-kontinentalen Buchhandels im 16. Jahrhundert [The English Eulenspiegel: The Eulenspiegel Reception as an Example of the English-Continental Book Trade in the 16th Century] (in German). Walter de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110253856. ISBN 9783110253856.

- Hotten, John C. (1860). Introduction. The Book of Vagabonds and Beggars with a Vocabulary of Their Language. By Anonymous. London: J.C. Hotten. OCLC 3080033. Archived from the original on October 26, 2022. Retrieved November 2, 2022 – via Project Gutenberg.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Jütte, Robert (1996). "Die Frau, die Kröte und der Spitalmeister: Zur Bedeutung der ethnographischen Methode für eine Sozial- und Kulturgeschichte der Medizin" [The Woman, the Toad and the Hospital Master: On the Significance of the Ethnographic Method for a Social and Cultural History of Medicine]. Historische Anthropologie (in German). 4 (2): 193–215. doi:10.7788/ha.1996.4.2.193. ISSN 0942-8704. S2CID 176510969.

- Kleinschmidt, Erich (1975). "Rotwelsch um 1500" [Rotwelsch around 1500]. Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur (in German). De Gruyter. 97: 217–229. doi:10.1515/bgsl.1975.1975.97.217. ISSN 0323-424X. S2CID 161998374.

- Kluge, Friedrich (1901). Rotwelsch. Quellen und Wortschatz der Gaunersprache und der verwandten Geheimsprachen [Rotwelsch. Sources and Vocabulary of the Rogue Language and Related Secret Languages] (in German). Straßburg: Karl J. Trübner. OCLC 3113515. Retrieved December 8, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Modestin, Georg (2020). "Chapter 2. The Metamorphoses of the Anti-Witchcraft Treatise Errores Gazariorum (15th Century)". In Goodare, Julian; Voltmer, Rita; Willumsen, Liv Helene (eds.). Demonology and Witch-Hunting in Early Modern Europe. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003007296. ISBN 9780367440527. S2CID 225420498. Retrieved November 5, 2022 – via Google Books.

- Rosenfeld, Moshe N. (1988). "Chapter 9. Early Yiddish in Non-Jewish Books". In Katz, Dovid (ed.). Dialects of the Yiddish Language: Winter Studies in Yiddish, Volume 2. Papers from the Second Annual Oxford Winter Symposium in Yiddish Language and Literature, 14–16 December 1986. Pergamon Press. ISBN 9780080365640. Retrieved November 5, 2022 – via Google Books.

- Wexler, Paul (1988). Three Heirs to a Judeo-Latin Legacy: Judeo-Ibero-Romance, Yiddish and Rotwelsch. Mediterranean language and culture monograph series. Vol. 3. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447028134. Retrieved September 9, 2023 – via Google Books.