Linaclotide

Linaclotide, (sold under the brand name Linzess in the US and Mexico, and as Constella elsewhere)[5] is a drug used to treat irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and chronic constipation with no known cause.[3][2] It has a black box warning about the risk of serious dehydration in children in the US; the most common adverse effects in others include diarrhea.[3]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Linzess |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a613007 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.243.239 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C59H79N15O21S6 |

| Molar mass | 1526.73 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

It is an oligo-peptide agonist of guanylate cyclase 2C and remains in the GI tract after it is taken by mouth. It was approved in the US and the European Union in 2012.[6]

It is marketed by Abbvie in the United states and by Astellas in Asia; Ironwood Pharmaceuticals was the originator.[7] In 2020, it was the 244th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 1 million prescriptions.[8][9]

Medical use

Linaclotide is indicated to treat irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and chronic constipation with no known cause.[3][2]

In June 2023, the indication was expanded in the US to include the treatment of functional constipation.[3][10]

Adverse effects

The US label has a black box warning to not use linaclotide in children less than six years old and to avoid in people from 6 to 18 years old, due to the risk of serious dehydration.[3]

More than 10% of people taking linaclotide have diarrhea. Between 1% and 10% of people have decreased appetite, dehydration, low potassium, dizziness when standing up too quickly, nausea, vomiting, urgent need to defecate, fecal incontinence, and bleeding in the colon, rectum, and anus.[2]

It has not been tested in pregnant women and it is unknown if it is excreted in breast milk.[2]

Pharmacology

Systemic absorption of the globular tetradecapeptide is minimal.[11][12]

Linaclotide, like the endogenous guanylin and uroguanylin it mimics, is an agonist that activates the cell surface receptor of guanylate cyclase 2C (GC-C).[11][3][13] The medication binds to the surface of the intestinal epithelial cells.[3] Linaclotide is minimally absorbed and it is undetectable in the systemic circulation at therapeutic doses.[11] Activation of GC-C increases cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP).[3] Elevated cGMP stimulates secretion of chloride and bicarbonate and water into the intestinal lumen, mainly by way of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) ion channel activation.[3][14] This results in increased intestinal fluid and accelerated transit.[3]

Chemistry

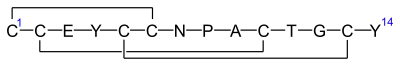

Linaclotide is a hybrid peptide design of the E.coli heat-stable enterotoxin (STa) and the endogenous peptide hormones endogenous guanylin and uroguanylin.[15][11][13] It is a synthetic tetradecapeptide (14 amino acid peptide) with the sequence CCEYCCNPACTGCY by one-letter abbreviation, or by three-letter abbreviation:[16]

H–Cys1–Cys2–Glu3–Tyr4–Cys5–Cys6–Asn7–Pro8–Ala9–Cys10–Thr11–Gly12–Cys13–Tyr14–OH

However, the actual structure of linaclotide is not fully specified without the three disulfide (R-S-S-R) bonds it contains, which are between Cys1 and Cys6, between Cys2 and Cys10, and between Cys5 and Cys13;[16] these are shown in exaggerated fashion in the line-angle graphic showing the chemical bonds within and between each amino acid (and their stereochemistries, see the infobox, above right), and are represented using a one-letter abbreviations in the following additional schematic:

A study in discovery synthesis reported that 2 of 14 strategies available to synthesize linaclotide were successful—the successful ones involving trityl protection of all cysteines, or trityl protection of all cysteines except Cys1 and Cys6, which were protected with tert-butylsulphenyl groups. The study also reported that solution-phase oxidation (disulfide formation) was advisable over solid-supported synthesis for linaclotide, and that the Cys1–Cys6 disulfide bridge was the most favored energetically.[16]

History

The drug was discovered at Microbia, Inc, which had been spun out of the Whitehead Institute in 1998 by postdocs from the lab of Gerald Fink to commercialize the lab's know-how and inventions related to microbial pathogens and biology.[17][18] In 2002 the company hired Mark Currie who had worked at the Searle division of Monsanto and then had gone to Sepracor.[17] Currie directed the efforts that led to the discovery of linaclotide, which was based on an enterotoxin produced by some strains of Escherichia coli that cause traveler's diarrhea.[19][20] The company started Phase I trials in 2004.[17]

Under a partnership agreement announced in 2007, between Forest Laboratories and Microbia, Forest would pay $70 million in licensing fees towards the development of linaclotide, with profits shared between the two companies in the US; Forest obtained exclusive rights to market in Canada and Mexico.[21] By 2010, Microbia had changed its name to Ironwood Pharmaceuticals and had licensed rights to distribute the drug in Europe to Almirall and had licensed Asian rights to Astellas Pharma.[22]

It was approved in the United States and in the European Union in 2012.[6]

Forest was acquired in 2014 and eventually became part of Allergan.[23] Allergan acquired rights from Almirall in 2015,[24] and in 2017, acquired remaining rights in most of the rest of the world, excluding North America, Japan, and China.[25]

Society and culture

Economics

In 2014, Ironwood and Forest then Allergan began running direct-to-consumer advertising which raised sales by 21%; campaigns in 2015 and 2016 raised sales by 27% and 30%.[26]

In 2017, the list price for linaclotide in the US was US$378 for 30 pills; Allergan and Ironwood increased the price of linaclotide to around $414 in 2018.[7]

References

- Oh SA (17 August 2011). "Macrocycle Milestone for Ironwood Pharma". The Haystack. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2017 – via CENBlog.org.

- "UK label: Linaclotide Summary of Product Characteristics". Electronic Medicines Compendium. September 2017. Archived from the original on 15 April 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- "Linzess- linaclotide capsule, gelatin coated". DailyMed. 31 August 2021. Archived from the original on 29 March 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- "Constella EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 24 May 2023. Archived from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- "Linaclotide - Ironwood Pharmaceuticals". AdisInsight. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- Yu SW, Rao SS (September 2014). "Advances in the management of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: the role of linaclotide". Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology. 7 (5): 193–205. doi:10.1177/1756283X14537882. PMC 4107700. PMID 25177366.

- Nocera J (9 January 2018). "How Allergan Continues to Make Drug Prices Insane". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 15 April 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- "Linaclotide - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- "FDA approves first treatment for pediatric functional constipation". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 12 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- Hussain ZH, Everhart K, Lacy BE (February 2015). "Treatment of Chronic Constipation: Prescription Medications and Surgical Therapies". Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 11 (2): 104–114. PMC 4836568. PMID 27099579.

- Corsetti M, Tack J (February 2013). "Linaclotide: A new drug for the treatment of chronic constipation and irritable bowel syndrome with constipation". United European Gastroenterology Journal. 1 (1): 7–20. doi:10.1177/2050640612474446. PMC 4040778. PMID 24917937.

- Love BL, Johnson A, Smith LS (July 2014). "Linaclotide: a novel agent for chronic constipation and irritable bowel syndrome". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 71 (13): 1081–1091. doi:10.2146/ajhp130575. PMID 24939497.

- Yu SW, Rao SS (September 2014). "Advances in the management of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: the role of linaclotide". Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology. 7 (5): 193–205. doi:10.1177/1756283X14537882. PMC 4107700. PMID 25177366.

- Braga Emidio N, Tran HN, Andersson A, Dawson PE, Albericio F, Vetter I, Muttenthaler M (June 2021). "Improving the Gastrointestinal Stability of Linaclotide". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 64 (12): 8384–8390. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00380. PMC 8237258. PMID 33979161.

- Góngora-Benítez M, Tulla-Puche J, Paradís-Bas M, Werbitzky O, Giraud M, Albericio F (2011). "Optimized Fmoc solid-phase synthesis of the cysteine-rich peptide linaclotide" (PDF). Biopolymers. 96 (1): 69–80. doi:10.1002/bip.21480. PMID 20560145. S2CID 46150263. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- Withers M (22 September 2004). "Druhunters". Paradigm Magazine, Whitehead Institute. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- Timmerman L (23 February 2009). "Xconomy: Renewables Aren't Just for Biofuels: Microbia Makes Industrial Chemicals a Bit Greener". Xconomy. Archived from the original on 16 April 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- Hornby PJ (2015). "Drug discovery approaches to irritable bowel syndrome". Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery. 10 (8): 809–824. doi:10.1517/17460441.2015.1049528. PMID 26193876. S2CID 207494271.

- "Director profile: Mark Currie, Ph.D." MUSC Foundation for Research Development. Archived from the original on 16 April 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- "Microbia, Forest Laboratories Announce Linaclotide Collaboration". FDA News. 17 September 2007. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- Pollack, Andrew (13 September 2010). "Drug for Irritable Bowel Achieves Goals in Trial". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- Jones S, Burdette K, Wieczner J (30 July 2015). "From Actavis to Allergan: One pharma company's wild dealmaking journey". Fortune. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- "Press release: Allergan Acquires Rights To Ironwoods Constella (Linaclotide) From Almirall In More Than 40 Countr". Allergan. 27 October 2015. Archived from the original on 15 April 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- "8-K" (PDF). Ironwood. 31 January 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- LaMotta L. "How DTC got things moving for Linzess". BioPharma Dive. Archived from the original on 15 April 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.