Lion and Sun

The Lion and Sun (Persian: شیر و خورشید, romanized: Šir o Xoršid, pronounced [ˌʃiːɾo xoɾˈʃiːd]; Classical Persian: [ˌʃeːɾu xʷuɾˈʃeːd]) is one of the main emblems of Iran (Persia), and was an element in Iran's national flag until the 1979 revolution and is still commonly used by opposition groups of the Islamic Republic government. The motif, which illustrates ancient and modern Iranian traditions, became a popular symbol in Iran in the 12th century.[1] The lion and sun symbol is based largely on astronomical and astrological configurations: the ancient sign of the sun in the house of Leo,[1][2] which itself is traced back to Babylonian astrology and Near Eastern traditions.[2][3]

| Lion and Sun Šir-o Xoršid شیر و خورشید | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) Lion and Sun | |

| Versions | |

Official simplified version used by the Imperial State of Iran from 1973 to 1979 | |

Official version used from 1964 to 1979 | |

| Other elements | The sun and the lion holding a shamshir |

| Use | Former emblem of Iran, former flag of Iran (before the 1979 revolution) |

The motif has many historical meanings. First, as a scientific and secular motif, it was only an astrological and zodiacal symbol. Under the Safavid and the first Qajar kings, it became more associated with Shia Islam.[1] During the Safavid era, the lion and sun stood for the two pillars of society, the state and the Islamic religion. It became a national emblem during the Qajar era. In the 19th century, European visitors at the Qajar court attributed the lion and sun to remote antiquity; since then, it has acquired a nationalistic interpretation.[1] During the reign of Fat′h-Ali Shah Qajar and his successors, the form of the motif was substantially changed. A crown was also placed on the top of the symbol to represent the monarchy. Beginning in the reign of Fat′h-Ali, the Islamic aspect of the monarchy was de-emphasized. This shift affected the symbolism of the emblem. The meaning of the symbol changed several times between the Qajar era and the 1979 revolution. The lion could be a symbol for Rostam, the legendary hero of Iranian mythology. The Sun has alternately been interpreted as symbol of motherland or Jamshid, the mythical Shah of Iran. The many historical meanings of the emblem have provided rich ground for competing symbols of Iranian identity. In the 20th century, some politicians and scholars suggested that the emblem should be replaced by other symbols such as the Derafsh Kaviani. However, the emblem remained the official symbol of Iran until the 1979 revolution, when the "Lion and Sun" symbol was removed from public spaces and government organizations, and replaced by the present-day emblem of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Origin

The lion and sun motif is based largely on astronomical and astrological configurations, and the ancient zodiacal sign of the sun in the house of Leo.[1][2] This symbol, which combines "ancient Iranian, Arab, Turkic and Mongol traditions", first became a popular symbol in the 12th century.[1] According to Afsaneh Najmabadi, the lion and sun motif has had "a unique success" among icons for signifying the modern Iranian identity, in that the symbol is influenced by all significant historical cultures of Iran and brings together Zoroastrian, Shia, Jewish, Turkic and Iranian symbolism.[4]

Zodiacal and Semitic roots

-850AD.png.webp)

According to Krappe, the astrological combination of the sun above a lion has become the coat of arms of Iran. In Islamic astrology the zodiacal Lion was the 'house' of the sun. This notion has "unquestionably" an ancient Mesopotamian origin. Since ancient times there was a close connection between the sun gods and the lion in the lore of the zodiac. It is known that, the sun, at its maximum strength between July 20 and August 20 was in the 'house' of the Lion.[3]

Krappe reviews the ancient Near Eastern tradition and how sun gods and divinities were closely connected to each other, and concludes that "the Persian solar lion, to this day the coat-of-arms of Iran, is evidently derived from the same ancient [Near Eastern] sun god". As an example, he notes that in Syria the lion was the symbol of the sun. In Canaan, a lion slayer hero was the son of Baa'l (i.e. Lord) Shamash, the great Semitic god of the sun. This lion slayer was originally a lion.[3] Another example is the great Semitic solar divinity Shamash, who could be portrayed as a lion. The same symbolism is observed in Ancient Egypt where in the temple of Dendera, Ahi the Great is called "the Lion of the Sun, and the lion who rises in the northern sky, the brilliant god who bears the sun".[3]

According to Kindermann the Iranian Imperial coat of arms had its predecessor in numismatics, which itself is based largely on astronomical and astrological configurations.[1][2] The constellation of Leo contains 27 stars and eight shapeless ones. Leo is "a fiction of grammarians ignorant of the skies, which owes its existence to false interpretations and arbitrary changes of the older star-names." It is impossible to determine exactly what was the origin of such interpretation from stars.[2] The Babylonians observed a heavenly hierarchy of kings in the zodiacal sign of Leo. They put the lion, as the king of their animal kingdom, into the place in the zodiac in which the summer solstice occurs. In the Babylonian zodiac, it became the symbol of the victory of the sun. Just as Jesus is called the Lion of Judah, and in Islamic traditions Ali Ibn Abu Talib is called the "Lion of God" (Asadullah) by Shiite Muslims, Hamzah, the uncle of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, was also called Lion of God.[2]

Iranian background

The male sun had always been associated with Iranian royalty: Iranian tradition recalls that Kayanids had a golden sun as their emblem. From the Greek historians of classical antiquity it is known that a crystal image of the sun adorned the royal tent of Darius III, that the Arsacid banner was adorned with the sun, and that the Sassanid standards had a red ball symbolizing the sun. The Byzantine chronicler Malalas records that the salutation of a letter from the "Persian king, the Sun of the East," was addressed to the "Roman Caesar, the Moon of the West". The Turanian king Afrasiab is recalled as saying: "I have heard from wise men that when the Moon of the Turan rises up it will be harmed by the Sun of the Iranians."[1] The sun was always imagined as male, and in some banners a figure of a male replaces the symbol of the sun. In others, a male figure accompanies the sun.[1]

Similarly, the lion too has always had a close association with Iranian kingship. The garments and throne decorations of the Achaemenid kings were embroidered with lion motifs. The crown of the half-Persian Seleucid king Antiochus I was adorned with a lion. In the investiture inscription of Ardashir I at Naqsh-e Rustam, the breast armour of the king is decorated with lions. Further, in some Iranian dialects the word for king (shah) is pronounced as sher, homonymous with the word for lion. Islamic, Turkish, and Mongol influences also stressed the symbolic association of the lion and royalty. The earliest evidence for the use of a lion on a standard comes from the Shahnameh, which noted that the feudal house of Godarz (presumably a family of Parthian or Sassanid times) adopted a golden lion for its devices.[1]

Islamic, Turkic, Mongolic roots

Islamic, Turkic, and Mongol traditions stressed the symbolic association of the lion and royalty in the lion and sun motif.[1] These cultures reaffirmed the charismatic power of the sun and the Mongols re-introduced the veneration of the sun, especially the sunrise.[1] The lion is probably represented more frequently and diversely than any other animal. In most forms, the lion has no apotropaic meaning and was merely decorative. However, it sometimes has an astrological or symbolic meaning. One of the popular forms of the lion is explicitly heraldic form, including in the Persian coat of arms (the lion and sun); the animal in the coat of arms of the Mamluk Baybars and perhaps also in that of the Rum Saldjukids of the name of Kilidi Arslan; and in numismatic representations.[2]

History

Iranian and Turkic dynasties

Ahmad Kasravi, Mojtaba Minovi and Saeed Nafisi's vast amount of literary and archaeological evidence show that the ancient zodiacal sign of the sun in the house of Leo become a popular emblematic figure in the 12th century.[1] (cf. Zodiacal origin, above) Fuat Köprülü suggests that the lion and sun on the Turkic and Mongolic flags and coins of these times are merely astrological signs and do not exemplify royalty.[5]

The lion and sun symbol first appears in the 13th century, most notably on the coinage of Kaykhusraw II, who was Sultan of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum from 1237 to 1246. These were "probably to exemplify the ruler's power."[1] The notion that "the sun [of the symbol] symbolized the Georgian wife of the king, is a myth, for on one issue 'the sun rests on the back of two lions rampant with their tails interlaced' [...] and on some issues the sun appears as a male bust."[1] Other chief occurrences of 12th- to 14th-century usage include:[1] an early 13th-century luster tile now in the Louvre; a c. 1330 Mamluk steel mirror from Syria or Egypt; on a ruined 12th- to 14th-century Arkhunid bridge near Baghdad; on some Ilkhanid coins; and on a 12th- or 13th-century bronze ewer now in the Golestan palace museum. In the latter, a rayed nimbus enclosing three female faces rests on a lion whose tail ends in a winged monster.

The use of the lion and sun symbol in a flag is first attested in a miniature painting illustrating a copy of Shahnameh Shams al-Din Kashani, an epic on Mongol conquest, dated 1423. The painting depicts several (Mongul?) horsemen approaching the walled city of Nishapur. One of the horsemen carries a banner that bears a lion passant with a rising sun on its back. The pole is tipped with a crescent moon. By the time of the Safavids (1501–1722), and the subsequent unification of Iran as a single state, the lion and sun had become a familiar sign, appearing on copper coins, on banners, and on works of art.[1] The Lion and Sun motif was also used on banners of the Mughals of India, notably those of Shah Jahan.[6]

Safavid dynasty

In Safavid times, the lion and sun stood for two pillars of the society, state and religion.[7] It is clear that, although various alams and banners were employed by the Safavids during their rule, especially the earlier Safavid kings, by the time of Shah Abbas, the lion and sun symbol had become one of the most popular emblems of Persia.[1]

According to Najmabadi, the Safavid interpretation of this symbol was based on a combination of mytho-histories and tales such as the Shahnameh, stories of Prophets, and other Islamic sources. For the Safavids, the Shah had two roles: king and holy man. This double meaning was associated with the genealogy of Iranian kings. Two males were key people in this paternity: Jamshid (mythical founder of an ancient Persian kingdom), and Ali (Shi'te first Imam). Jamshid was affiliated with the sun and Ali was affiliated with the lion (Zul-faqar).[8]

Shahbazi suggest that the association may originally have been based on a learned interpretation of the Shahnameh's references to 'the Sun of Iran' and 'the Moon of the Turanians.[1] (cf: the "Roman"—i.e., Byzantine—king as the "Moon of the West" in the Iranian background section). Since Ottoman sultans, the new sovereigns of 'Rum', had adopted the moon crescent as their dynastic and ultimately national emblem, the Safavids of Persia, needed to have a their own dynastic and national emblem. Therefore, Safavids chose the lion and sun motif.[1] Besides, the Jamshid, the sun had two other important meanings for the Safavids. The sense of time was organized around the solar system which was distinct from the Arab-Islamic lunar system. Astrological meaning and the sense of cosmos was mediated through that. Through the zodiac the sun was linked to Leo which was the most auspicious house of the sun. Therefore, for the Safavids, the sign of lion and sun condensed the double meaning of the Shah—king and holy man (Jamshid and Ali)—through the auspicious zodiac sign of the sun in the house of Leo and brought the cosmic-earthy pair (king and Imam) together.[9]

In seeking the Safavi interpretation of the lion and sun motif, Shahbazi suggests that the Safavids had reinterpreted the lion as symbolizing Imam ʿAlī and the sun as typifying the "glory of religion", a substitute for the ancient farr-e dīn.[1] They reintroduced the ancient concept of God-given Glory (farr), reinterpreted as "light" in Islamic Iran, and the Prophet and Ali "had been credited with the possession of a divine light of lights (nūr al-anwār) of leadership, which was represented as a blazing halo." They attributed such qualities to Ali and sought the king's genealogy through the Shia Fourth Imam's mother to the royal Sasanian house.[1]

Afsharids and Zand dynasties

The royal seal of Nader Shah in 1746 was the lion and sun motif. In this seal, the sun bears the word Al-Molkollah (Arabic: The earth of God).[10] Two swords of Karim Khan Zand have gold-inlaid inscriptions which refer to the: "... celestial lion ... pointing to the astrological relationship to the Zodiac sign of Leo ..." Another record of this motif is the Lion and Sun symbol on a tombstone of a Zand soldier.[10]

Royal seal of Nader Shah, 1764[10]

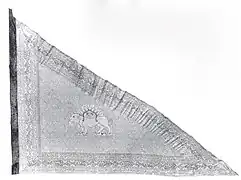

Royal seal of Nader Shah, 1764[10] Nader Shah Flag

Nader Shah Flag

Islamic-Iranian Interpretation

The earliest known Qajar lion and sun symbol is on the coinage of Aqa Mohammad Shah Qajar, minted in 1796 on the occasion of Shah's coronation. The coin bears the name of the new king underneath the sun and Ali (the first Shi'ite Imam) underneath the lion's belly. Both names are invoked and this coin suggest that this motif still stands for the king (sun) and religion (lion), "Iranization and Imamification of sovereignty".[7] In the Qajar period the emblem can be found on Jewish marriage certificates (ketubas) and Shi'ite mourning of muharram banners.[11]

Nationalistic interpretation

During the reign of the second Qajar shah, Fat′h Ali Shah Qajar, we observe the beginning of a shift in political culture from the Safavi concept of rule. The Islamic component of the ruler was de-emphasized, if not completely abounded. This shift coincides with the first archaeological surveys of Europeans in Iran and the re-introduction of the past pre-Islamic history of Iran to Iranians. Fat'h Ali Shah tried to affiliate his sovereignty with the glorious years of pre-Islamic Iran. Literary evidence and documents from his time suggest that the sun in the lion and sun motif was the symbol of the king and a metaphor of Jamshid. Referring to Rostam, the mythical hero of Iran in Shahnameh, and the fact that lion was the symbol of Rostam, the lion received a nationalistic interpretation. The lion was the symbol of heroes of Iran who are ready to protect the country against enemies.[12] Fat'h Ali Shah addresses the meanings of the signs in two of his poems:[13]

Fat'h Ali shah, the Turki Shah, the universe-enlightening Jamshid

The Lord of the country Iran, the universe-adoring sun

Also:

Iran, the gorg of lions, sun the Shah of Iran

It's for this that the lion-and-sun is marked on the banner of Darius

It was also during this time that he had the Sun Throne, the imperial throne of Persia, constructed.

In the 19th century, European visitors at the Qajar court attributed the lion and sun to remote antiquity, which prompted Mohammad Shah Qajar to give it a "nationalistic interpretation."[1] In a decree published in 1846, it is stated that "For each sovereign state an emblem is established, and for the august state of Persia, too, the Order of Lion and Sun has been in use, an ensign which is nearly three thousand years old—indeed dating from before the age of Zoroaster. And the reason for its currency may have been as follows. In the religion of Zoroaster, the sun is considered the revealer of all things and nourisher of the universe [...], hence, they venerated it". This is followed by an astrological rationale for having selecting the "selected the sun in the house of Leo as the emblem of the august state of Persia." The decree then claims that use of Order of the Lion and Sun had existed in pre-Islamic Zoroastrian Iran until the worship of the sun was abolished by Muslims.[1] Piemontese suggests that in this decree, "native political considerations and anachronistic historical facts are mixed with curious astrological arguments"[14] At the time, the lion and sun symbol stood the state, the monarchy, and the nation of Iran, associated all with a pre-Islamic history.[14]

Order of the Lion and the Sun

The Imperial Order of the Lion and the Sun was instituted by Fat’h Ali Shah of the Qajar dynasty in 1808 to honour foreign officials (later extended to Persians) who had rendered distinguished services to Persia.

Substantial changes in the motif

Another change under the second and third Qajar king was the Africanization of the motif.[15] At this time, the lion was an African lion which had a longer mane and bigger body compared to the Persian lion. Yahya Zoka suggests that this modification was influenced by contact with Europeans.[15]

According to Shahbazi. the Zu'l-faqar and the lion decorated the Iranian flags at the time. It seems that towards the end of Fath' Ali Shah's reign the two logos were combined and the lion representing Ali was given Ali's saber, Zu'l-faqar.[1]

According to Najmabadi, occasionally we come across the lion and sun with a sword in the lion's paw and with a crown during this period. The Mohammad Shah's decree in 1836 states that the lion must erectly stand, bear a saber ("to make it explicitly stands for the military prowess of the state"). The crown was also added as a symbol of royalty rather than for any particular Qajar monarch. The decree states that the emblem is at once the national, royal, and the state emblem of Iran.[16] In this period the lion was depicted as more masculine and the sun was female. Before this time the sun could be male or female and the lion was represented as a swordless, friendly and subdued seated animal.[15]

The crown over the lion and sun configuration consolidated the association of the symbol with the monarchy. The sun lost its importance as the icon of kingship and the Kiani Crown became the primary symbol of the Qajar monarchy.[16] Under Nasir al-Din Shah, logos varied from seated, swordless lions to standing and sword-bearing lions.[16] In February 1873, the decree for Order of Aftab (Nishan-i Afab) was issued by Nasi-al Din Shah.[15]

Emblem of Persia during Fat'h Ali Shah

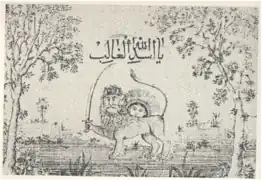

Emblem of Persia during Fat'h Ali Shah Logo of Akhbardar al-Khalafah-i Tehran Newspaper, 5 February 1851

Logo of Akhbardar al-Khalafah-i Tehran Newspaper, 5 February 1851

The lion and Sun, Golistan Palace, Qajar dynasty

The lion and Sun, Golistan Palace, Qajar dynasty.svg.png.webp) Imperial Coat of arms of Iran. Qajar dynasty (1907–1925)

Imperial Coat of arms of Iran. Qajar dynasty (1907–1925).svg.png.webp)

After the Constitutional Revolution

In the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution of 1906, the lion and sun motif in the flag of Iran was described as a passant lion that holds a saber in its paw and with the sun in its background.[1] A decree dated September 4, 1910 specified the exact details of the logo, including the lion's tail ("like an italic S"), the position and the size of the lion, his paw, the sword, and the sun.[18]

Najmabadi observes a parallel symbolism on wall hangings produced between the lion/sun and Reza Khan/motherland, after Reza Khan's successful coup. The coy sun is protected by the lion and Rezakhan is the hero who should protect the motherland.[19] Under Reza Shah the sun's female facial features were removed and the sun was portrayed more realistically and merely with rays. In the military contexts the Pahlavi crown was added to the motif.[1]

The Pahlavis adopted the lion and sun emblem from Qajars, but they replaced the Qajar Crown with the Pahlavi Crown.[6] Pahlavis reintroduced the Persian symbolism to the motif. As is discussed in Persian traditions, the lion had been the symbol of kingship and symbol of Rustam's heroism in Shahnameh.[20]

The many historical meanings of the emblem, while provide a solid ground for its power as the national emblem of Iran, have also provided the rich ground for competing symbols of Iranian identity.[21] One important campaign to abolish the emblem was initiated by Mojtaba Minuvi in 1929. In a report prepared at the request of the Iranian embassy in London, he insisted that the lion and sun is Turkic in origin. He recommended that the government replaces it with Derafsh-e-Kaviani: "One cannot attributed a national historical story to the lion-and-sun emblem, for it has no connection to ancient pre-Islamic history, there is no evidence that Iranians designed or created it.... We might as well get rid of this remnant of the Turkish people and adopt the flag that symbolizes our mythical grandeur, that is Derafsh-e-Kaviani". His suggestion was ignored.[22] The symbol was challenged during World War I, while Hasan Taqizadeh was publishing the Derafsh-e-Kaviani newspaper in Berlin. In his newspaper, he argued that the lion and sun is neither Iranian in origin nor very ancient as people assume. He insisted that the lion and sun should be replaced by the more Iranian symbol of Derafsh-e-Kaviani. [23]

Flag of Iran, 1907–1979

Flag of Iran, 1907–1979 Coat of Arms of Pahlavi dynasty

Coat of Arms of Pahlavi dynasty.svg.png.webp) Imperial Emblem of Iran during Pahlavi Dynasty

Imperial Emblem of Iran during Pahlavi Dynasty.svg.png.webp) Naval Jack of Iran (1926–74)

Naval Jack of Iran (1926–74) A Lion and Sun insignia in the Niavaran Palace, Tehran

A Lion and Sun insignia in the Niavaran Palace, Tehran

After the 1979 revolution

The Lion and Sun remained the official emblem of Iran until after the 1979 revolution, when the Lion and Sun symbol was—by decree—removed from public spaces and government organizations and replaced by the present-day Emblem of Iran.[24] For the Islamic revolution, the lion and sun symbol allegedly resembled the "oppressive Westernizing monarchy" that had to be replaced, despite the fact the symbol had old Shi'a meanings and the lion was associated with Ali.[20] In the present day, the lion and the sun emblem is still used by a segment of the Iranian community in exile as the symbol of opposition to the Islamic Republic.[25] Several exiled opposition groups, including the monarchists, and People's Mojahedin continue to use the lion and sun emblem. In Los Angeles and cities with large Iranian communities the lion and sun emblem is largely used on mugs, Iranian flags, and souvenirs to an extent that far surpasses its display during the years of monarchy in the homeland.[24]

International recognition

The Lion and Sun is an officially recognized but currently unused emblem of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. The Red Lion and Sun Society of Iran (جمعیت شیر و خورشید سرخ ایران) was admitted to the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement in 1929.[26]

On September 4, 1980, the newly proclaimed Islamic Republic of Iran replaced the Red Lion and Sun with the Red Crescent, consistent with most other Muslim nations. Though the Red Lion and Sun has now fallen into disuse, Iran has in the past reserved the right to take it up again at any time; the Geneva Conventions continue to recognize it as an official emblem, and that status was confirmed by Protocol III in 2005 even as it added the Red Crystal.[27]

In literature

- Anton Chekhov has a short story titled "The Lion and the Sun". The story is about a mayor who had "long been desirous of receiving the Persian order of The Lion and the Sun".[28]

Gallery

Iranian variations

Uzbekistani Banknote (reverse). The lion and sun emblem on the banknote is taken from the painting on Shir Dar (Lion Gate) in Samarqand, built 1627 AD[29]

Uzbekistani Banknote (reverse). The lion and sun emblem on the banknote is taken from the painting on Shir Dar (Lion Gate) in Samarqand, built 1627 AD[29] Flag of Iran in the early 19th century depicted by Drouville.

Flag of Iran in the early 19th century depicted by Drouville. Flag of Iran (1886 AD) reserved for state buildings and royal monuments, forts and ports, and anything related to the state and royalty.

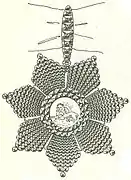

Flag of Iran (1886 AD) reserved for state buildings and royal monuments, forts and ports, and anything related to the state and royalty. Order of Aftab, 1902 AD

Order of Aftab, 1902 AD

The Lion and Sun Plate in British Museum, London

The Lion and Sun Plate in British Museum, London

Banknote of Persia - 50 tomans; mid-19th century

Banknote of Persia - 50 tomans; mid-19th century.jpg.webp) Obverse of the 2000 dinar (2 qiran) Iranian coin of the Qajar dynasty, with the emblem of the Lion & Sun & the Kiani crown. Date: 1326.

Obverse of the 2000 dinar (2 qiran) Iranian coin of the Qajar dynasty, with the emblem of the Lion & Sun & the Kiani crown. Date: 1326. Lion and Sun of the Persian shah at Kniže & Comp. in Vienna's Graben.

Lion and Sun of the Persian shah at Kniže & Comp. in Vienna's Graben. Ketubbah from Persia, 1840s

Ketubbah from Persia, 1840s Red Lion and Sun Society of Iran

Red Lion and Sun Society of Iran.jpg.webp) Mosaic representations the lion and sun on the façade of the Sher Dor Medressa (1636) at the Registan in Samarkand, Uzbekistan

Mosaic representations the lion and sun on the façade of the Sher Dor Medressa (1636) at the Registan in Samarkand, Uzbekistan Tajikistan (1992-1993)

Tajikistan (1992-1993) Emblem of Samarkand (Uzbekistan)

Emblem of Samarkand (Uzbekistan)

Other (non-Iranian) variants

alchemical illustration in the Rosary of the Philosophers

alchemical illustration in the Rosary of the Philosophers Bernardo Diedo (1432), Koper, Slovenia

Bernardo Diedo (1432), Koper, Slovenia

Lion d'Arras

Lion d'Arras

.svg.png.webp)

Fontaine family (Magland, France)

Fontaine family (Magland, France) Flag of Mughal Empire

Flag of Mughal Empire Flag of Chesalles-sur-Moudon

Flag of Chesalles-sur-Moudon

See also

Citations

- Shahbazi 2001.

- Kindermann 1986.

- Krappe 1945.

- Joseph & Najmabadi 2002.

- Köprülü 1990.

- Eskandari-Qajar 2009.

- Najmabadi 2005, p. 70.

- Najmabadi 2005, pp. 68–69.

- Najmabadi 2005, p. 69.

- Khorasani 2006, p. 326.

- Najmabadi 2005, p. 65.

- Najmabadi 2005, p. 70–71.

- Najmabadi 2005, p. 72.

- Najmabadi 2005, p. 82.

- Najmabadi 2005, p. 83.

- Najmabadi 2005, p. 81.

- Barker 1995, p. 137.

- Najmabadi 2005, p. 86.

- Najmabadi 2005, pp. 88–96.

- Babayan 2002.

- Najmabadi 2005, p. 87.

- Najmabadi 2005, pp. 86–87.

- Marashi 2008, p. 78.

- Najmabadi 2005, pp. 87–88.

- McKeever, Amy (29 November 2022). "Why Iran's flag is at the center of controversy at the World Cup". National Geographic.

- Burchill et al. 2005, p. 137.

- "Protocol additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Adoption of an Additional Distinctive Emblem (Protocol III), 8 December 2005". INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS.

- Chekhov, Anton. "The Lion and the Sun".

- Nafisi 1949.

General references

- Babayan, Kathryn (2002), Mystics, monarchs, and messiahs: cultural landscapes of early modern Iran, Harvard College, p. 491, ISBN 0-932885-28-4

- Barker, Patricia L. (1995), Islamic Textiles, British Museum Press, p. 137, ISBN 0-7141-2522-9

- Burchill, Richard; White, N. D.; Morris, Justin; McCoubrey, H. (2005), International conflict and security law: essays in memory of Hilaire McCoubrey, Vol. 10, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521845311

- Eskandari-Qajar, Manoutchehr M. (2009), Emblems of Qajar (Kadjar) Rulers: The Lion and the Sun, The Qajar(Kadjar) Pages, retrieved 2009-10-10

- Köprülü, Fuat (1990). "Bayrak". Daneshnameye Jahan-e Eslam (Encyclopaedia of the World of Islam From Encyclopedia of Turk) (in Persian). The Encyclopaedia Islamica Foundation. Archived from the original on 2011-07-10.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Joseph, Suad; Najmabadi, Afsaneh (2002), Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures: Family, law, and politics, Netherlands: Brill Academic Publisher, p. 524

- Kindermann, H. (1986), "Al-Asad", Encyclopedia of Islam, vol. 1, Leiden, the Netherlands: E.J.Brill, pp. 681–3

- Khorasani, Manouchehr M. (2006), Arms and Armor from Iran: The Bronze Age to the End of the QajarPeriod. (First ed.), Germany: Verlag

- Krappe, Alexander H. (Jul–Sep 1945), "The Anatolian Lion God", Journal of the American Oriental Society, American Oriental Society, 65 (3): 144–154, doi:10.2307/595818, JSTOR 595818

- Marashi, Afshin (2008), Nationalizing Iran: Culture, Power, and the State, 1870-1940, Published by University of Washington Press

- Nafisi, Saeed (1949), Derafsh-e Iran va Shir-o-Khoshid (The Banner of Iran and the Lion and the Sun) (in Persian), Tehran: Chap-e Rangin

- Najmabadi, Afsaneh (2005), "II", Gender and sexual anxieties of Iranian Modernity, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-24262-9

- Shahbazi, Shapur A. (2001), "Flags (of Persia)", in E. Yarshater; et al. (eds.), Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. 10

External links

Media related to Lion and Sun at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lion and Sun at Wikimedia Commons