Lipid peroxidation

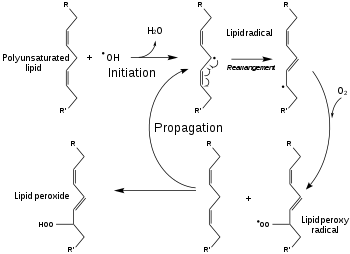

Lipid peroxidation is the chain of reactions of oxidative degradation of lipids. It is the process in which free radicals "steal" electrons from the lipids in cell membranes, resulting in cell damage. This process proceeds by a free radical chain reaction mechanism. It most often affects polyunsaturated fatty acids, because they contain multiple double bonds in between which lie methylene bridges (-CH2-) that possess especially reactive hydrogen atoms. As with any radical reaction, the reaction consists of three major steps: initiation, propagation, and termination. The chemical products of this oxidation are known as lipid peroxides or lipid oxidation products (LOPs).

Initiation

Initiation is the step in which a fatty acid radical is produced. The most notable initiators in living cells are reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as OH· and HOO·, which combines with a hydrogen atom to make water and a fatty acid radical.

Propagation

The fatty acid radical is not a very stable molecule, so it reacts readily with molecular oxygen, thereby creating a peroxyl-fatty acid radical. This radical is also an unstable species that reacts with another free fatty acid, producing a different fatty acid radical and a lipid peroxide, or a cyclic peroxide if it had reacted with itself. This cycle continues, as the new fatty acid radical reacts in the same way.

Termination

When a radical reacts with a non-radical, it can produce another radical, which is why the process is called a "chain reaction mechanism". The radical reaction stops when two radicals react and produce a non-radical species. This happens only when the concentration of radical species is high enough for there to be a high probability of collision of two radicals. Living organisms have different molecules that speed up termination by neutralizing free radicals and, therefore, protecting the cell membrane. Antioxidants such as vitamin C and vitamin E may inhibit lipid peroxidation.[1] Other anti-oxidants made within the body include the enzymes superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase. An alternative, pharmaceutical method employs the isotope effect on lipid peroxidation of deuterated polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) at the methylene bridges (bis-allylic sites) between double bonds, which leads to the inhibition of the chain reaction. Such D-PUFAs, for example, 11,11-D2-ethyl linoleate, suppress lipid peroxidation even at relatively low levels of incorporation into membranes.[2]

Final products of lipid peroxidation

The end products of lipid peroxidation are reactive aldehydes, such as malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE), the second one being known also as "second messenger of free radicals" and major bioactive marker of lipid peroxidation, due to its numerous biological activities resembling activities of reactive oxygen h species.[3]

Hazards

If not terminated fast enough, there will be damage to the cell membrane, which consists mainly of lipids. Phototherapy may cause hemolysis by rupturing red blood cell cell membranes in this way.[4]

In addition, end-products of lipid peroxidation may be mutagenic and carcinogenic.[5] For instance, the end-product MDA reacts with deoxyadenosine and deoxyguanosine in DNA, forming DNA adducts to them, primarily M1G.[5]

Reactive aldehydes can also form Michael adducts or Schiff bases with thiol or amine groups in amino acid side chains. Thus, they are able to inactivate sensitive proteins through electrophilic stress.[6]

The toxicity of lipid hydroperoxides to animals is best illustrated by the lethal phenotype of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) knockout mice. These animals do not survive past embryonic day 8, indicating that the removal of lipid hydroperoxides is essential for mammalian life.[7]

On the other hand, it's unclear whether dietary lipid peroxides are bioavailable and play a role in disease, as a healthy human body has protective mechanisms in place against such hazards.[8]

Tests

Certain diagnostic tests are available for the quantification of the end-products of lipid peroxidation, to be specific, malondialdehyde (MDA).[5] The most commonly used test is called a TBARS Assay (thiobarbituric acid reactive substances assay). Thiobarbituric acid reacts with malondialdehyde to yield a fluorescent product. However, there are other sources of malondialdehyde, so this test is not completely specific for lipid peroxidation.[9]

In recent years, development of immunochemical detection of HNE-histidine adducts opened more advanced methodological possibilities for qualitative and quantitative detection of lipid peroxidation in various human and animal tissues[3] as well as in body fluids, including human serum and plasma samples.[10]

See also

References

- Huang, Han-Yao; Appel, Lawrence J.; Croft, Kevin D.; Miller, Edgar R.; Mori, Trevor A.; Puddey, Ian B. (September 2002). "Effects of vitamin C and vitamin E on in vivo lipid peroxidation: results of a randomized controlled trial". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 76 (3): 549–555. doi:10.1093/ajcn/76.3.549. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 12197998.

- Hill, S.; et al. (2012). "Small amounts of isotope-reinforced PUFAs suppress lipid autoxidation". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 53 (4): 893–906. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.06.004. PMC 3437768. PMID 22705367.

- http://informahealthcare.com/toc/fra/44/10

- Ostrea, Enrique M.; Cepeda, Eugene E.; Fleury, Cheryl A.; Balun, James E. (1985). "Red Cell Membrane Lipid Peroxidation and Hemolysis Secondary to Phototherapy". Acta Paediatrica. 74 (3): 378–381. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.1985.tb10987.x. PMID 4003061. S2CID 39547619.

- Marnett, LJ (March 1999). "Lipid peroxidation-DNA damage by malondialdehyde". Mutation Research. 424 (1–2): 83–95. doi:10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00010-x. PMID 10064852.

- Bochkov, Valery N.; Oskolkova, Olga V.; Birukov, Konstantin G.; Levonen, Anna-Liisa; Binder, Christoph J.; Stockl, Johannes (2010). "Generation and Biological Activities of Oxidized Phospholipids". Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 12 (8): 1009–1059. doi:10.1089/ars.2009.2597. PMC 3121779. PMID 19686040.

- Muller, F. L., Lustgarten, M. S., Jang, Y., Richardson, A. and Van Remmen, H. (2007). "Trends in oxidative aging theories". Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 43 (4): 477–503. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.034. PMID 17640558.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Vieira, Samantha A.; Zhang, Guodong; Decker, Eric A. (2017). "Biological Implications of Lipid Oxidation Products". Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 94 (3): 339–351. doi:10.1007/s11746-017-2958-2. S2CID 90319530.

- Trevisan, M.; Browne, R; Ram, M; Muti, P; Freudenheim, J; Carosella, A. M.; Armstrong, D (2001). "Correlates of Markers of Oxidative Status in the General Population". American Journal of Epidemiology. 154 (4): 348–56. doi:10.1093/aje/154.4.348. PMID 11495858.

- Weber, D; Milkovic, L; Bennett, S. J.; Griffiths, H. R.; Zarkovic, N; Grune, T (2013). "Measurement of HNE-protein adducts in human plasma and serum by ELISA—Comparison of two primary antibodies". Redox Biology. 1 (1): 226–233. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2013.01.012. PMC 3757688. PMID 24024156.

External links

- Lipid+peroxidation at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)