Syriac literature

Syriac literature is literature in the Syriac language. It is a tradition going back to the Late Antiquity. It is strongly associated with Syriac Christianity.[2][3][4]

Terminology

In modern Syriac studies,[5] and also within the wider field of Aramaic studies,[6] the term Syriac literature is most commonly used as a shortened designation for Classical Syriac literature, that is written in Classical Syriac language, an old literary and liturgical language of Syriac Christianity.[7] It is sometimes also used as a designation for Modern Syriac literature or Neo-Syriac literature, written in Modern Syriac (Eastern Neo-Aramaic) languages. In the wider sense, the term is often used as designation for both Classical Syriac and Modern Syriac literature,[4] but its historical scope is even wider, since Syrian/Syriac labels were originally used by ancient Greeks as designations for Aramaic language in general, including literature written in all variants of that language.[8][9] Such plurality of meanings, both in ancient literary texts and in modern scholarly works, is further enhanced by the conventional scholarly exclusion of Western Aramaic heritage from the Syriac corpus, a practice that stands in contradiction not only with historical scope of the term, but also with well attested self-designations of native Syriac-speaking communities. Since the term Syriac literature continues to be used differently among scholars, its meanings are remaining dependent on the context of every particular use.[10][11][12]

Classical

Early Syriac texts date to the 2nd century, notably the old versions Syriac Bible and the Diatessaron Gospel harmony. The bulk of Syriac literary production dates to between the 4th and 8th centuries. Syriac literacy survived into the 9th century, but Syriac Christian authors in this period increasingly write in Arabic.

"Classical Syriac language" is the term for the literary language as was developed by the 3rd century. The language of the first three centuries of the Christian era is also known as "Old Syriac" (but sometimes subsumed under "Classical Syriac").

The earliest Christian literature in Syriac was biblical translation, the Peshitta and the Diatessaron. Bardaisan was an important non-Christian (Gnostic) author of the 2nd century, but most of his works are lost and only known from later references. An important testimony of early Syriac is the letter of Mara bar Serapion, possibly written in the late 1st century (but extant in a 6th- or 7th-century copy).

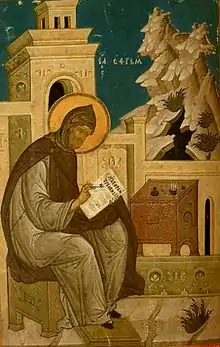

The 4th century is considered to be the golden age of Syriac literature. The two giants of this period are Aphrahat, writing homilies for the church in the Persian Empire, and Ephrem the Syrian, writing hymns, poetry and prose for the church just within the Roman Empire. The next two centuries, which are in many ways a continuation of the golden age, sees important Syriac poets and theologians: Jacob of Serugh, Narsai, Philoxenus of Mabbog, Babai the Great, Isaac of Nineveh and Jacob of Edessa.

There were substantial efforts to translate Greek texts into Syriac. A number of works originally written in Greek survive only in Syriac translation. Among these are several works by Severus of Antioch (d. 538), translated by Paul of Edessa (fl. 624). A Life of Severus was written by Athanasius I Gammolo (d. 635). National Library of Russia, Codex Syriac 1 is a manuscript of a Syriac version of the Eusebian Ecclesiastical History dated to AD 462.

After the Islamic conquests of the mid-7th century, the process of hellenization of Syriac, which was prominent in the sixth and seventh centuries, slowed and ceased. Syriac entered a silver age from around the ninth century. The works of this period were more encyclopedic and scholastic, and include the biblical commentators Ishodad of Merv and Dionysius bar Salibi. Crowning the silver age of Syriac literature is the thirteenth-century polymath Bar-Hebraeus.

The conversion of the Mongols to Islam began a period of retreat and hardship for Syriac Christianity and its adherents. However, there has been a continuous stream of Syriac literature in Upper Mesopotamia and the Levant from the fourteenth century through to the present day.

Modern

The emergence of vernacular Neo-Aramaic (Modern Syriac) is conventionally dated to the late medieval period, but there are a number of authors that continued to produce literary works in Classical Syriac up to the early modern period, and literary Syriac (ܟܬܒܢܝܐ Kṯāḇānāyā) continues to be in use among members of the Syriac Orthodox Church.

Modern Syriac literature includes works in various colloquial Eastern Aramaic Neo-Aramaic languages still spoken by Assyrian Christians. This Neo-Syriac literature bears a dual tradition: it continues the traditions of the Syriac literature of the past, and it incorporates a converging stream of the less homogeneous spoken language. The first such flourishing of Neo-Syriac was the seventeenth century literature of the School of Alqosh, in northern Iraq. This literature led to the establishment of Assyrian Neo-Aramaic and so called Chaldean Neo-Aramaic as written literary languages. In the nineteenth century, printing presses were established in Urmia, in northern Iran. This led to the establishment of the 'General Urmian' dialect of Assyrian Neo-Aramaic as the standard in much Neo-Syriac Assyrian literature. The comparative ease of modern publishing methods has encouraged other colloquial Neo-Aramaic languages, like Turoyo and Senaya, to begin to produce literature.

List of writers

- Mara bar Serapion (author of an early (1st century?) Syriac letter preserved in a 6th or 7th-century ms.)

- Bardaisan (2nd century)

- Aphrahat 270-345

- Ephrem the Syrian (d. 373)

- Cyrillona (4th century)

- Isaac of Antioch (5th century)

- Narsai (5th century)

- Stephen Bar Sudhaile (late 5th c.)

- Jacob of Serugh (d. 521)

- Philoxenus of Mabbug (d. 523)

- Paul of Edessa (fl. 624), translator of the (Greek) works of Severus of Antioch (d. 538)

- Sergius of Reshaina (d. 536)

- John of Ephesus (d. 588)

- Peter III of Raqqa (d. 591)

- Babai the Great (d. 628)

- Athanasius I Gammolo (d. 635)

- Marutha of Tikrit (d. 649)

- Sahdona (d. c. 650)

- John bar Penkaye (late 7th c.)

- Isaac of Nineveh (d. 700)

- Jacob of Edessa (d. 708)

- Theodore Bar Konai (8th century)

- John of Dalyatha (d. c. 780)

- Theodore Abu Qurrah (d. 823)

- Anthony of Tagrit (9th century)

- Theodosius Romanus (9th century)

- Thomas of Marga (9th century)

- Jacob Bar-Salibi (12th century)

- Bar Hebraeus (13th century)

- Giwargis Warda (13th century)

- Abdisho bar Berika (d. 1318)

See also

References

- This manuscript was previously misidentified as a translation of John Chrysostom's Homilies on the Gospel of John. It has subsequently been identified as missing pages from a Syriac witness to the Asceticon. See J. Edward Walters, "Schøyen MS 574: Missing Pages From a Syriac Witness of the Asceticon of Abba Isaiah of Scete," Le Muséon 124 (1-2), 2011: 1-10.

- Wright 1894.

- Baumstark 1922.

- Brock 1997.

- Brock 2015a, p. 7-19.

- Brock 1989, p. 11–23.

- Healey 2012, p. 643-644.

- Millar 2006, p. 383-384.

- Minov 2020, p. 256-257.

- Butts 2011, p. 390-391.

- Healey 2012, p. 638.

- Butts 2019, p. 222–242.

Sources

- Barsoum, Ignatius Aphram (2000). The History of Syriac Literature and Sciences. Pueblo, CO: Passeggiata Press. ISBN 9781578891030.

- Baumstark, Anton (1922). Geschichte der syrischen Literatur, mit Ausschluss der christlich-palästinensischen Texte. Bonn: A. Marcus und E. Weber Verlag. ISBN 9783110821253.

- Bettiolo, Paolo (2006). "Syriac Literature". Patrology V: The Eastern Fathers from the Council of Chalcedon (451) to John of Damascus (†750). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 407–490. ISBN 9780227679791.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1980). "Syriac Historical Writing: A Survey of the Main Sources" (PDF). Journal of the Iraq Academy: Syriac Corporation. 5 (1979-1980): 1–30, (326-297).

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1989). "Three Thousand Years of Aramaic Literature". ARAM Periodical. 1 (1): 11–23.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1992). Studies in Syriac Christianity: History, Literature, and Theology. Aldershot: Variorum. ISBN 9780860783053.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1996). Syriac Studies: A Classified Bibliography, 1960-1990. Kaslik: Parole de l'Orient.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1997). A Brief Outline of Syriac Literature. Kottayam: St. Ephrem Ecumenical Research Institute.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2004a). "The Earliest Syriac Literature". The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 161–172. ISBN 9780521460835.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2004b). "Ephrem and the Syriac Tradition". The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 362–372. ISBN 9780521460835.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2006a). Fire from Heaven: Studies in Syriac Theology and Liturgy. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754659082.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2006b). "Syriac Literature: A Crossroads of Cultures" (PDF). Parole de l'Orient. 31: 17–35.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2011). "Melkite literature in Syriac". Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 285–286.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2015a). "The Syriac Language and its Place within Aramaic" (PDF). Hekamtho: Syrian Orthodox Theological Journal. 1 (1): 7–19.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2015b). "Charting the Hellenization of a Literary Culture: The Case of Syriac". Intellectual History of the Islamicate World. 3 (1–2): 98–124. doi:10.1163/2212943X-00301005.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2017). "Scribal Tradition and the Transmission of Syriac Literature in Late Antiquity and Early Islam". Scribal Practices and the Social Construction of Knowledge in Antiquity. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. pp. 61–68. ISBN 9789042933149.

- Butts, Aaron M. (2011). "Syriac Language". Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 390–391.

- Butts, Aaron M. (2019). "The Classical Syriac Language". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 222–242.

- Debié, Muriel (2000). "Record Keeping and Chronicle Writing in Antioch and Edessa". ARAM Periodical. 12 (1–2): 409–417. doi:10.2143/ARAM.12.0.504478.

- Debié, Muriel (2009). "Syriac Historiography and Identity Formation". Church History and Religious Culture. 89 (1–3): 93–114. doi:10.1163/187124109X408014.

- Debié, Muriel (2010). "Writing History as Histoires: The Biographical Dimension of East Syriac Historiography". Writing True Stories: Historians and Hagiographers in the Late Antique and Medieval Near East. Turnhout: Brepols. pp. 43–75. ISBN 9782503527864.

- Debié, Muriel (2010). "Les apocryphes et l'histoire en syriaque". Sur les pas des Araméens chrétiens: Mélanges offerts à Alain Desreumaux. Paris: Geuthner. pp. 63–76.

- Debié, Muriel; Taylor, David G. K. (2012). "Syriac and Syro-Arabic Historical Writing, c. 500-c. 1400". The Oxford History of Historical Writing. Vol. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 155–179. ISBN 9780199236428.

- Debié, Muriel (2015). "Theophanes' Oriental Source: What Can We Learn from Syriac Historiography?". Travaux et Mémoires. 19: 365–382.

- Duval, Rubens (1907) [1899]. La Littérature Syriaque (3rd ed.). Paris: Lecoffre.

- Duval, Rubens (2013) [1907]. Syriac Literature: An English Translation of La Littérature Syriaque. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 9781611439625.

- Ebied, Rifaat (1972). "Some Syriac Manuscripts from the Collection of Sir E. A. Wallis Budge". Symposium Syriacum, 1972. Roma: Pontificium Institutum Orientalium Studiorum. pp. 509–539.

- Harrak, Amir (2003). "Patriarchal Funerary Inscriptions in the Monastery of Rabban Hormizd: Types, Literary Origins, and Purpose" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 6 (2): 235–264.

- Harrak, Amir (2011). "Chronicles, Syriac". Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 98–99.

- Heal, Kristian S. (2015). "Five Kinds of Rewriting: Appropriation, Influence and the Manuscript History of Early Syriac Literature". Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies. 15: 51–65. doi:10.31826/9781463236915-006. ISBN 9781463236915.

- Healey, John F. (2012). "Syriac". The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Berlin-Boston: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 637–652. ISBN 9783110251586.

- Kannengiesser, Charles (2004). "Syriac Christian Literature". Handbook of Patristic Exegesis: The Bible in Ancient Christianity. Vol. 2. Leiden-Boston: Brill. pp. 1377–1446. ISBN 9789004137349.

- Macomber, William F. (1969). "A Funeral Madraša on the Assassination of Mar Hnanišo". Mémorial Mgr Gabriel Khouri-Sarkis (1898-1968). Louvain: Imprimerie orientaliste. pp. 263–273.

- McCollum, Adam C. (2015). "Greek Literature in the Christian East: Translations into Syriac, Georgian, and Armenian". Intellectual History of the Islamicate World. 3 (1–2): 15–65. doi:10.1163/2212943X-00301003.

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. The Church in history. Vol. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 9780881410563.

- Millar, Fergus (2006). Rome, the Greek World, and the East: The Greek World, the Jews, and the East. Vol. 3. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807876657.

- Minov, Sergey (2020). Memory and Identity in the Syriac Cave of Treasures: Rewriting the Bible in Sasanian Iran. Leiden-Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004445512.

- Moss, Cyril (1962). Catalogue of Syriac Printed Books and Related Literature in the British Museum. London: Trustees of the British Museum.

- Murre van den Berg, Heleen (1999). From a Spoken to a Written Language: The Introduction and Development of Literary Urmia Aramaic in the Nineteenth Century. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. ISBN 9789062589814.

- Murre van den Berg, Heleen (2006). "A Neo-Aramaic Gospel Lectionary Translation by Israel of Alqosh". Loquentes linguis: Linguistic and Oriental Studies in Honour of Fabrizio A. Pennacchietti. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 523–533. ISBN 9783447054843.

- Possekel, Ute (2019). "The Emergence of Syriac Literature to AD 400". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 309–326. ISBN 9781138899018.

- Reinink, Gerrit J. (1993). "The Beginnings of Syriac Apologetic Literature in Response to Islam". Oriens Christianus. 77: 165–187.

- Rompay, Lucas van (2000). "Past and Present Perceptions of Syriac Literary Tradition" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 3 (1): 71–103. doi:10.31826/hug-2010-030105. S2CID 212688244.

- Saint-Laurent, Jeanne-Nicole (2019). "Syriac Hagiographic Literature". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 339–354. ISBN 9781138899018.

- Taylor, David G. K. (2011). "Syriac Lexicography". Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 391–393.

- Weltecke, Dorothea; Younansardaroud, Helen (2019). "The Renaissance of Syriac Literature in the Twelfth–Thirteenth Centuries". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 698–717. ISBN 9781138899018.

- Witakowski, Witold (1986). "Chronicles of Edessa". Orientalia Suecana. 33-35 (1984-1986): 487–498.

- Witakowski, Witold (2000). "The Chronicle of Eusebius: Its Type and Continuation in Syriac Historiography". ARAM Periodical. 12 (1–2): 419–437. doi:10.2143/ARAM.12.0.504479.

- Witakowski, Witold (2007). "Syriac Historiographical Sources". Byzantines and Crusaders in Non-Greek Sources, 1025-1204. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 253–282.

- Witakowski, Witold (2011). "Historiography, Syriac". Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 199–203.

- Wood, Philip (2019). "Historiography in the Syriac-Speaking World, 300–1000". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 405–421. ISBN 9781138899018.

- Wright, William (1894). A Short History of Syriac Literature. London: Adam and Charles Black.

External links

- HUGOYE: Journal of Syriac Studies Archived 2015-05-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Syriac Literature

- Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Computing Institute

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.