List of former cathedrals in Great Britain

This is a list of former or once proposed cathedrals in Great Britain.

Introduction

The term former cathedral in this list includes any Christian[1] church (building) in Great Britain which has been the seat of a bishop,[2] but is not so any longer. The status of a cathedral, for the purpose of this list, does not depend on whether the church concerned is known to have had a formal "throne" (or cathedra) nor whether a formal territory or diocese was attached to the church. Before the development of dioceses, which began earlier in England than in Scotland and Wales, "such bishops as there were either lived in monasteries or were 'wandering bishops'".[3] This list, therefore, includes early "bishop's churches" (a "proto-cathedral" is similar).

A former cathedral may be the building that lost its cathedral status or its site, whether now vacant or not. The loss of status may be because that bishopric is extinct, or was relocated. Sometimes a new cathedral was built near an older one, with the older building then used for other purposes, or demolished. Such a building or site counts as a former cathedral. Where a cathedral is modified or rebuilt on substantially the same site in a series of developments over time, the earlier versions are not counted here as former cathedrals (except for cases where the original cathedral was totally rebuilt on broadly the same site but on a visibly different alignment, such as London's "Old St Paul's" and Winchester's "Old Minster" which are listed here).

A former pro-cathedral is a church or former church (or site of a former church) which was once a temporary cathedral officially performing that role until its expected replacement by an intended permanent cathedral took place, usually by completion of a new cathedral built for that purpose.

A once proposed cathedral is a church that was proposed (usually by a church or civil authority) as a future cathedral but, for some reason, did not become one. Known examples will be included in this list. Sometimes a second such proposal for the same church succeeded: as long as that church retains its cathedral status it will not feature in this List.

For information on current cathedrals in Great Britain please refer to:

List of cathedrals in England, or List of cathedrals in Scotland, or List of cathedrals in Wales, as appropriate.

England

References are to the English church's current use or its use prior to deconsecration.

Former cathedrals founded before 1066

survivors becoming Church of England at the Reformation (1540)

| Location | Image | Name | Dates | Notes | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bradwell-on-Sea, Essex |    |

Chapel of St Peter-on-the-Wall; original dedication uncertain | 654 – 664 | Founded by St Cedd in 653 after a mission to the East Saxons from London by Saint Mellitus failed in c. 616.[4] His chosen site was the former Roman Saxon Shore fort of Othona,[5] near Bradwell-on-Sea. A stone cathedral[6] was built of Roman materials,[7] but Cedd died in 664. A third mission in c. 675, by St Erkenwald from London succeeded. After centuries as a chapel-of-ease, then as a barn (when it lost its original W porch and E (chancel) apse, and had a large section of its S wall removed for access),[8] the structure was restored and re-consecrated in 1920.[9] Served from the parish church of St Thomas, Bradwell, it is in regular use for worship.[10] | 51°44′07″N 0°56′24″E |

| Canterbury, Kent |   | St Martin's Church, Canterbury | 597 – 602 | The oldest church in continuous use in the English-speaking world; parts date from before the Roman withdrawal from Britain. It was used for Christian worship from c. 580, before St Augustine landed. He used it as his proto-cathedral,[11] while his new cathedral was being built. Since then, St Martin's has been a parish church.[12] | 51.277989°N 1.093825°E |

| Chester-le-Street, County Durham |   | Collegiate Church of St Mary and St Cuthbert | c. 883 – c. 995 | After being driven out of Lindisfarne, seat of the Diocese of Lindisfarne, by Viking raids in 875, the community of monks journeyed widely carrying the body of St Cuthbert and other relics. In 883 they settled at the site of the Roman fort of Concangis.[13] Land was granted to them by Guthred, and they built a wooden church within the Roman fort to house both Cuthbert's relics and the cathedra of the bishop. In 995, fear of renewed raids caused the community to flee again, (via Ripon) finally to Durham. The current church was built from 1056 on the site of the wooden cathedral, and was restored c. 1883 for the 1,000th anniversary of the arrival of St Cuthbert's community. | 54.855944°N 1.571972°W |

| Crediton, Devon |  | Collegiate Church of the Holy Cross and the Mother of Him Who Hung Thereon | 909 – 1050 | A purported charter of 739 by King Æthelheard of Wessex granted land here to Forthhere (d. 737) for a monastery. A new see, for Devon and Cornwall, was created in the early 10th century out of the diocese of Sherborne, possibly first at Tawton, but certainly by 909 at Crediton. The monastic cathedral of St Mary was replaced, after the see moved to Exeter in 1050, by a new collegiate church newly (by 1237) dedicated to the Holy Cross and St Mary.[14] | 50°47′22.70″N 3°39′8.21″W |

| Dinuurrin, (Bodmin), Cornwall |  | site uncertain; dedication unknown | 9th century | Dinuurrin is a placename known to us only as the seat of the early Cornish bishop[15] Kenstec, who sometime between 833 and 870 declared his obedience to Canterbury.[16] There are good reasons[17] to believe the site was on high ground at the northern edge of Bodmin. The early 16th-century Guild Chapel of the Holy Rood was built in such a place, but fell into ruin after the reformation – only the roofless shell of its tower (shown), now known as "Berry Tower", remains. But the site is ancient and had high status (the chapel unusually enjoyed rights of baptism and burial),[18] and it is thought likely that Kenstec's seat was here. The site, amid cemeteries, is accessed from Cross Lane. | 50.47525°N 4.71791°W |

| Dommoc, Suffolk | site unknown; dedication unknown | c. 630 – c. 850 | Several locations have been suggested for the Anglo-Saxon see of East Anglia, founded by St Felix, notably two sites long lost to the sea by coastal erosion: (1) Dunwich,[19] once an important medieval town now submerged; or (2) the old Roman Saxon Shore fort of Walton, now off the coast at Felixstowe.[20] Two sets of co-ordinates are offered: one, very approximate, for Dunwich; the second for Walton's offshore masonry remains.[21] The diocese was split c. 673, with an additional see created at Elmham. The list of Dommoc bishops ended with the Danish invasions of c. 850. | ||

| Dorchester on Thames, Oxfordshire |   | Abbey Church of St Peter & St Paul, Dorchester | 635 – c. 660; then c. 675 – 737; and c. 875 – 1072 | The first West Saxon see was founded here c. 635, translated to Winchester c. 660. It later became a Mercian bishopric twice: firstly, in c. 675 until merged into the medieval diocese of Leicester c. 737,[22] secondly, in c. 875 when the sees of Leicester and Lindsey were transferred here for safety from Viking attack. That see was translated to Lincoln in 1072. The secular canons of 635–1140 were replaced by Augustinian canons. After the dissolution in 1536 the chancel of the abbey church was bought by Richard Beauforest and on his death in 1555 it passed to the parish, the whole then became the parish church.[23] There is a 14th-century Jesse window,[24] and a reconstructed shrine to St Birinus. | 51°38′37″N 1°09′51″W |

| Durham, County Durham |

| The White Church (Alba Ecclesia) (almost certainly dedicated to St Cuthbert) | c. 998 – c. 1104 | Towards the end of the 10th century the community of St Cuthbert (settled at Chester-Le-Street since 883)[25] feared renewed Viking attacks.[26] Carrying St Cuthbert's body they once again sought safety, and journeyed south to arrive in 995 at Durham, which provided a secure site. After using one or two temporary wooden structures, in 998 the community began building a stone (therefore "white") church into which Cuthbert's relics were transferred.[25] This cruciform stone Anglo-Saxon cathedral, with a central and a western tower. was completed c. 1020. In 1083 the second Norman bishop, William de St-Calais, suppressed the community of Cuthbert, replacing them with Benedictine monks from Evesham, who had lately restored Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey.[27] Durham thus became a cathedral priory, and in 1093 Bishop William began construction of the Norman cathedral that underlies today's cathedral. By 1104 building had progressed sufficiently to allow the transfer of Cuthbert's relics from The White Church to the new cathedral followed by the former's demolition. There is good evidence that the foundations of The White Church lie beneath the cloister garth (shown) in the monastic buildings just south of the present cathedral, to which the coordinates relate.[28][29] | 54°46′24″N 1°34′36″W |

| Elmham, Norfolk |  | dedication unknown | 673 – c. 850; and c. 950 - 1071 | The see of Elmham, now almost certainly to be identified as North Elmham,[30] was created c. 673 when the East Anglian diocese, with its see at Dommoc, was split. The succession of Elmham bishops was interrupted between c. 850 and c. 950 owing to Viking raids. The see, restored only at Elmham, was translated to Thetford in 1071. Church remains, in the hands of English Heritage, are held to date from c. 1100, the earlier cathedral having probably been wooden. | 52°45′20″N 0°56′41″E |

| Exeter, Devon |

| Church of St Mary Major, Exeter | 1050 – c.1133 | From a 7th-century monastery, the Minster of Saint Mary and Saint Peter became the seat of Bishop Leofric when the see of Crediton was translated to Exeter in 1050[31] The dual dedication may mean the minster comprised two churches.[32][33] The Norman cathedral was begun in 1114 just east of St Mary's and took the dedication to St Peter (and perhaps its site), while to the west St Mary's was retained to serve local people. By 1222 St Mary's had become the parish church of St Mary Major[34] (upper image). By the mid-19th century, it was thought to be too close to the cathedral's west front, and demolished 1865. The finial from the steeple of its replacement (demolished 1971) is sited on the cathedral green to show where the tower of that church once stood (lower image). | 50°43′21″N 3°31′47″W |

| Hexham, Northumberland |    | Priory and Parish Church of St Andrew, Hexham | 678 – c. 821 | In 678, Theodore of Tarsus divided the diocese of York, appointing a Bishop of Bernicia with his seat at Hexham Abbey[35] and/or Lindisfarne Abbey. However, in 682 a separate bishopric of Hexham was created, with a diocese covering "the district between the rivers Aln and Tees".[36] Bishops continued to be appointed erratically until 821, when the diocese reverted into Lindisfarne. In 875 Danes razed the Abbey to the ground. From 1113 an Augustinian Priory used the site (dissolved 1537). Since then the priory church has been a parish church, undergoing a rebuild of the east end in 1858 and in the very early 20th century a rebuilding of the nave, completed 1908. Evidence remains of its past status: Wilfrid's crypt (3rd image) and a frithstool, an early bishop's cathedra (in the foreground of the 2nd image), both of the 7th century. | 54°58′17″N 2°06′10″W |

| Hoxne, Suffolk |

|

Church of St Peter and St Paul, with St Edmund[37] | c. 926 – c. 952 (possibly mid-11th century) | In 926[38] the newly-appointed Bishop of London, Theodred, was also given episcopal authority in Suffolk and Norfolk by King Æthelstan. Theodred founded a new see in the church dedicated to St Æthelberht[39] at Hoxne.[40] At this time the two East Anglian sees of Dommoc and Elmham had been in abeyance since c. 850[41] due to repeated Viking attacks. Theodred died c. 952, after the see of Elmham had been restored with the appointment of Bishop Aethelweald (946-949), so Theodred's former see was subsumed within the restored diocese. The Hoxne church remained collegiate until at least the death of Bishop Ælfric II in 1038 and it may have retained the status of a second cathedral for East Anglia since, according to the Domesday Book, Hoxne was still the see for Suffolk into the reign of St Edward the Confessor (1042-1066).[42] The parish church, dating from the 14th century, likely occupies the ancient church site.[43] | 52.352192°N 1.201719°E |

| Leicester, Leicestershire |    | St Nicholas' Church, Leicester; site probable; original dedication unknown | 679 – 874? | The Diocese of Lichfield was divided by 679, forming four new dioceses, including one for the Middle Angles at Leicester.[22] The location of the 7th-century cathedral here is not known with certainty, but was very likely St Nicholas'[44] with clear early Anglo-Saxon origins and incorporating Roman materials.[45] It stands between the sites of the Roman baths and the Roman forum. Overrun by Danes c.875 the see was suppressed and merged with Dorchester on Thames.[22] St Nicholas' is now a parish church. The modern Diocese of Leicester was created in 1927 (out of Peterborough), with the 12th-century church of St Martin becoming its cathedral. | 52.635147°N 1.140914°W |

| Lindisfarne, Northumberland |

|

Church of St Mary the Virgin, Lindisfarne; original dedication unknown | 635 – 875 | A monastery was founded in 635 by King Oswald for St Aidan as the site for a cathedral for the northern part of the kingdom of Northumbria. Viking raids from 793 led to its destruction in 875. The community fled, with the relics of Saint Cuthbert, settling at Chester-Le-Street in 883, then Durham in 995. The see was translated to Durham, which founded a sub-priory here in 1083 with a church dedicated to St Peter (dissolved 1537).[46] Extensive priory remains (upper image) are held by English Heritage. The parish church of St Mary the Virgin (lower image) stands near the priory ruins on the site of Aidan's wooden cathedral. | 55.669389°N 1.801922°W |

| City of London, London |

|

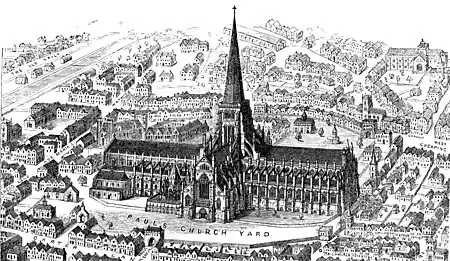

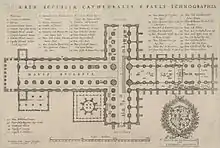

Old St Paul's Cathedral, London | 604 – 1666 | This former cathedral was begun by the Normans in 1087, in succession to a series of three, all probably wooden, Anglo-Saxon cathedrals dedicated to St Paul, built in 604, c.675, and c.962. All were destroyed by fire, in c.616, 962 (by Vikings), and 1087.[47] This stone-built cathedral was also destroyed by fire in 1666, and replaced by the extant St Paul's Cathedral, built 1675–1710 on a different alignment in a very different architectural style. A 1561 illustration is shown, together with a plan of the structure (East is to the right in both). | 51.513611°N 0.098333°E |

| Padstow, Cornwall |

|

St Petroc's Church | 518 - 564? | By tradition Saint Petroc landed in 518 at Trebetherick, near what became Padstow (Petroc-stow = holy place of Petroc) after his death. He succeeded the hermit-bishop Wethinoc, who had founded a monastery. Petroc named it Lanwethinoc[48] and its church became Petroc's cathedral for Cornwall.[49] He died there c.564. A Viking attack razed the monastery in 981, so the monks moved to Bodmin, with Petroc's relics. The parish church dates from the 15th century but is believed to occupy the original monastic site. | 50.541269°N 4.942856°W |

| Ramsbury, Wiltshire |

|

Church of the Holy Cross, Ramsbury; site probable; original dedication unknown | 909 – 1058 | The Ramsbury bishopric was created for Wiltshire in 909 out of the Diocese of Winchester, but in 1058 it was united with the Diocese of Sherborne to form the Diocese of Salisbury, with its see then at Old Sarum. The former Ramsbury Cathedral is thought to have been situated where the 13th-century parish church of the Holy Cross now stands.[50] | 51°26′31″N 1°36′22″W |

| Repton, Derbyshire |   |

St Wystan's church; original dedication uncertain | c. 655 – 669 | An early- to mid-7th-century double monastery of Celtic origin here provided the supposed[51] original see for Mercia. Four bishops of Mercia are named, before St Chad moved the see to Lichfield when he became bishop in 669,[52] though they may have been peripatetic (having no defined territory).[53] The Repton monastery was destroyed when a Danish army over-wintered here in 873/4, though the c. 720 crypt of the abbey church (shown), survived and was used for Mercian royal burials. An Augustinian priory, founded c. 1158 and dedicated to St Wystan, used the same site (dissolved 1538).[54] Traces of priory buildings exist in Repton School (1559),[53] adjacent to St Wystan's church, now the parish church. | 52.84115°N 1.551695°W |

| St Germans, Cornwall |   | Priory Church of St Germanus | early 10th century – c. 1027 | King Athelstan (of England – which by then included Cornwall) appointed Conan as Bishop of Cornwall in c.936, with his see at St Germans.[55] Some earlier bishops of Cornwall (after Kenstec) were probably also based at St Germans. Lyfing, Bishop of Crediton, became additionally Bishop of Cornwall in c.1027, uniting the two sees at Crediton. The former cathedral at St Germans became collegiate c.1050, then an Augustinian priory founded c.1184 (dissolved 1539), leaving a parish church with some Norman fabric. | 50°23′48″N 4°18′35″W |

| Selsey, Sussex |

|

Selsey Abbey; site uncertain; dedication unclear | c. 681 – c.1075 | With the help of King Æthelwealh of Sussex, St Wilfrid founded a monastery and bishopric here in 681. He returned to the north c. 686, but the see was revived in c. 709. It was translated to Chichester immediately following the Council of London in 1075. Centuries of coastal erosion seem to lie behind a tradition that the site of the cathedral is now under the sea,[56] but the most likely site[57] is the 13th-century St Wilfrid's Chapel, Church Norton (shown). This is the chancel left behind when the rest of the parish church was dismantled (1864–66) and moved to Selsey village to become (with additions) the new parish church. The chapel was dedicated to St Wilfrid in 1917.[58][59][60] | 50°45′18″N 0°45′55″W |

| Sherborne, Dorset |

| Abbey Church of St Mary the Virgin | 705 – 1075 | In 705 the see was created for western Wessex, from part of the diocese of Winchester. In 909 new dioceses were created for Devon and Cornwall (at Crediton, though possibly at Tawton first), Wiltshire (at Ramsbury), and Somerset (at Wells), leaving the Sherborne see with Dorset only. Ramsbury rejoined Sherborne in 1058, and the see was translated to Old Sarum in 1075. Sherborne became a Benedictine priory in c. 993, an abbey in 1122 (dissolved 1539). Its church was bought by townspeople to be the parish church. Neighbouring Sherborne School incorporates some abbey buildings. | 50°56′48″N 2°31′00″W |

| Soham, Cambridgeshire |

|

St Andrew's Church, Soham; status uncertain | c. 630?; and c. 900 – c. 950 | A monastery of c. 630 here, supposedly founded by St Felix, may have had an early cathedral for East Anglia (soon translated to Dommoc). It was destroyed by Danes c. 870, but when rebuilt c. 900 may then have served as a cathedral - when the sees of Dommoc and Elmham had both ceased to function - until eclipsed by Ely Cathedral. Ancient traces remain in St Andrew's parish church.[61][62] | 52.333478°N 0.336942°E |

| Syddensis, Lindsey, Lincolnshire |   | site uncertain; original dedication unknown | c. 680 – c. 875 | The Mercian diocese founded by St Chad at Lichfield was divided in 678 and a cathedral built at the city of Syddensis in Lindsey for the Bishop of Lindsey. Syddensis is a placename otherwise unknown to us, but the search for the 'lost' see of Lindsey was long focused on the Anglo-Saxon minster at Stow-in-Lindsey.[63] That view has now been largely discounted in favour of a site (still uncertain) in Lincoln itself.[64] A strong case has been advanced[65] for the see having been located in the Lincoln suburb of Wigford, with its Anglo-Saxon churches of St Mary-le-Wigford (upper image) or St Peter-at-Gowts (lower image) prime candidates for the site of the (probably wooden) earlier cathedral. The see of Lindsey suffered from Danish invasion and so was translated to Dorchester-on-Thames in the mid-9th century.[66] St Mary's and St Peter's remain as parish churches. | 53°13′36″N 0°32′28″W |

| Tawton, (later Bishop's Tawton), Devon |

| Church dedicated to St Peter recorded in 1256;[67] later, Church of St John the Baptist; status doubtful | c. 905 – c.909 | Some reported 16th/17th-century sources[68][69] allege that the see for the first bishop for Devon (a diocese created by dividing the Diocese of Sherborne in the early 10th century) was at Tawton (later Bishop's Tawton).[53][70] The sources claim that Werstan held office from its creation in 905 to his death in 906; his successor (Putta) was killed in 909 on his way to Crediton; and his successor (Eadwulf) immediately moved the see to Crediton. Any link between a 10th-century bishop's church here and the extant parish church of St John the Baptist (shown) is conjectural, but there are remains of a modest "bishop's palace" at Court Farm, next to the church, used for centuries by the diocesan bishops, and the parish was a bishop's peculiar.[71] The co-ordinates given are for the 14th-century parish church, restored in the 19th century. | 51°03′08″N 4°02′53″W |

| Wells, Somerset |

| Minster Church of St Andrew | 909 – 1175 | In c. 909 the Diocese of Sherborne, covering South-West England, was divided creating several new dioceses. Wells was chosen as the see for Somerset, and the town's minster, founded c. 705, became its cathedral. In 1090 a new bishop moved the see to Bath Abbey and built a new cathedral there. Despite Wells' loss of status, in 1176 a much larger building was begun, further north and on a different alignment, forming the basis of the present Wells Cathedral. (Wells became a cathedral city again in 1245.) The only accessible material from the Anglo-Saxon former cathedral is the supposed font (shown), dated c.700. The coordinates given are of the cloister garth where excavations of 1978–80 located foundations of the former cathedral, though they have been left almost undisturbed.[72][73] | 51°12′36″N 2°38′38″W |

| Welsh Bicknor, Herefordshire (was in Monmouthshire until 1844) |  | St Margaret's Church; whether site of former cathedral is uncertain | 6th century – 8th? century | Welsh Bicknor is in the area of Archenfield (once part of the British-Welsh petty kingdom of Ergyng before the area became part of England). The British bishop-saint Dubricius (otherwise Dyfrig) (c. 465 – c. 550) founded several monasteries in the area and has been called the first bishop of Ergyng.[74][75] According to a charter in the Book of Llandaff his episcopal place (in Latin, "episcopalis locus") was at "Lann Custenhinn Garth Benni", identified with Constantine[76] which location has been determined as Welsh Bicknor.[77][78] With few local residents; its church, dedicated to St Margaret of Antioch, was closed by the Diocese of Hereford in 2010 and is now privately owned. Entirely new-built in 1858–59 to relieve overcrowding, it replaced a much older church on the same pre-Conquest "monastic or clas church" site.[79] | 51.8561°N 2.5935°W |

| The Old Minster, Winchester, Hampshire |  | The Old Minster, Winchester | c. 660 – 1093 | The Old Minster was built about the year 660[80] as the seat of the first bishop of Winchester, a new diocese following the ending of Dorchester on Thames as the see for the bishopric of Wessex. Known as The Old Minster from at least 901 (when The New Minster was built next to it, to the north), it was much enlarged in the 10th century, becoming a Benedictine cathedral priory in 964.[81] It was demolished, together with the New Minster, in 1093,[82] when the new Norman cathedral (the basis of the extant Winchester Cathedral) was sufficiently complete. The Norman cathedral was built just south of the Old Minster, on a different alignment, so parts of the Old Minster's foundations lie under the extant cathedral while the rest lie outside the cathedral, to the north, marked out with paviours (shown). | 51.0611°N 1.3136°W |

Former cathedrals founded (or proposed) between 1066 and 1539

survivors becoming Church of England at the Reformation (1540)

| Location | Image | Name | Dates | Notes | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bath, Somerset |   | Priory Church of St Peter & St Paul | 1090 – 1539 | After the destruction of a 7th-century abbey by Danes, a 10th-century Benedictine abbey was destroyed in 1087 and rebuilt. The see for Somerset was translated from Wells to Bath in 1090, which became a cathedral priory. Bath was co-cathedral with Glastonbury 1195–1218, then co-cathedral with Wells from 1245 until Bath Priory was dissolved in 1539, just after it had been largely rebuilt. Queen Elizabeth I gave the priory church to be Bath's parish church in 1572, which led to years of restoration. More restoration by Gilbert Scott followed in the 1860s. | 51°22′53″N 2°21′32″W[83] |

| Chester, Cheshire |    | Collegiate Church of St John the Baptist | 1075 – 1102 | A minster of the 7th century was refounded c. 1057 by Leofric as a college, dedicated to The Holy Rood and St John the Baptist. It became the cathedral for the Mercian diocese when the see was translated to Chester from Lichfield following a decree of the Council of London in 1075.[84] The see was again translated by 1102 to Coventry, the diocesan title becoming 'Coventry and Lichfield'. St Johns retained a high status within the diocese, and the diocesan bishop was sometimes styled 'Bishop of Chester'. The Diocese of Chester was re-founded in 1541, using the former Abbey Church of St Werburgh for its cathedral. | 53°11′20″N 2°53′09″W |

| Coventry, (Warwickshire), West Midlands |  | Cathedral Priory of St Mary, St Peter and St Osburga[85][86] | 1102 – 1539 | A Benedictine abbey was founded 1043 on the site of a Saxon nunnery founded by St Osburga. The see of Lichfield, which was translated to Chester in 1075, moved to Coventry by 1102 (the diocese of Coventry and Lichfield thus having two cathedrals until 1539 when this cathedral priory was dissolved). The priory church was sold for demolition in 1545 but significant remains have been located and preserved (shown).[87] | 52.4089°N 1.5085°W |

| Glastonbury, Somerset |   | Abbey Church of St Mary, Glastonbury | 1195 – 1218 | At this ancient Christian site, dating from at least the early 7th century, a Benedictine abbey flourished from the year 940. In 1195 the Bishop of Bath was also made Abbot of Glastonbury, styling himself Bishop of Bath and Glastonbury. The monks opposed this move, in 1218 the pope agreed with them and the title reverted.[88] The abbey was dissolved in 1539, the site sold, and the buildings used as a source of building stone. In 1908-09 the site and ruins were acquired indirectly by the Church of England. The site is now in the hands of the charitable Glastonbury Abbey Trust. | 51.145648°N 2.715318°W |

| Old Sarum, Wiltshire |   | Old Sarum Cathedral; dedication unknown | 1075 – 1219 | Among other buildings, the Normans built a cathedral (model shown, upper image) on this Iron Age hillfort site, moving the see here from Sherborne in 1075. The see was translated to Salisbury in 1219. Stone from Old Sarum was moved there to be reused in the new building, leaving foundations (outlined, lower image). | 51°05′39″N 1°48′23″W |

| Thetford, Norfolk |  | Minster of St Mary Major (St Mary the Great) | 1071 – c. 1094 | This minster became the see for East Anglia when Herfast, the last Bishop of Elmham, moved his see from North Elmham to Thetford in 1071. With the help of his archdeadon, Herman, he spent the next 10 years trying to move the see to Bury St Edmunds Abbey against the wishes of Abbot Baldwin, and failed. In c. 1094 the see moved to Norwich. From 1103 the building housed a Cluniac priory before it relocated in 1107. In 1335 the abandoned site was given to the Dominicans for a friary (dissolved 1538). The site is thought to be near Thetford Grammar School (shown) (co-ordinates given) which incorporates some remains of the friary.[89] | 52.413527°N 0.744477°E |

| Westbury-on-Trym, Gloucestershire |  | Holy Trinity Church, Westbury-on-Trym | proposed | A minster was founded in c. 795, and re-founded as a Benedictine priory by Bishop Oswald of Worcester c. 962. The monks left to start Ramsey Abbey c. 974. A monastery was re-founded by St Wulfstan, Bishop of Worcester c. 1093, but the church became collegiate c. 1194. From 1286 Bishop Giffard intended Westbury as a second cathedral, but he died 1302. A similar plan by Bishop Carpenter in 1455 led to a change of dedication from "St Mary" to "Holy Trinity", and his use of the title "Bishop of Worcester and Westbury", but this last ceased on his death in 1476. | 51.49395°N 2.616°W |

Former Church of England cathedrals founded (or proposed) from 1540 to the present

| Location | Image | Name | Dates | Notes | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aldfield, North Yorkshire |   | Abbey Church of St Mary, (Fountains Abbey) | proposed | Known as Fountains Abbey, this Cistercian house of 1132 was dissolved 1539. In 1540 King Henry VIII chose its church as the cathedral for a diocese to cover Lancashire, some of Yorkshire, and much of Cumberland and Westmorland.[90] The proposal was abandoned and the site sold, in favour of a new Diocese of Chester, covering the same area plus Cheshire.[91] The site is now owned by National Trust and managed by English Heritage. | 54°06′36″N 1°34′53″W |

| Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk |  | Abbey Church of St Mary & St Edmund | proposed | Founded c. 633, the remains of St Edmund, martyred in 870 were brought here in 903. The church became collegiate c. 925., then a Benedictine abbey in 1020, dissolved 1539. King Henry VIII proposed the abbey church as a cathedral in 1540,[90] but the site was sold. The diocese was eventually created in 1914 from parts of the Diocese of Norwich and the Diocese of Ely, with the church of St James, adjacent to the abbey ruins, becoming its cathedral. | 52.2441°N 0.7192°E |

| Colchester, Essex |  | Abbey Church of St John the Baptist, Colchester | proposed | A Benedictine monastery founded here in 1096 was dissolved in 1539. The abbey church was unsuccessfully proposed as a cathedral for Essex (probably as a substitute for Waltham Abbey) in c. 1540.[90] Only the abbey's gatehouse remains. | 51.885544°N 0.901297°E |

| Coventry, (Warwickshire), West Midlands |   | (1st) Cathedral of St Michael, Coventry | 1918 – 1962 (although in ruins 1940 - 1962) | This very large medieval parish church, dating from c. 1300 (collegiate from 1908) became a cathedral in 1918 when the modern Diocese of Coventry was created from part of the Diocese of Worcester. It was almost totally destroyed by aerial bombing on the night of 14 November 1940, during the Second World War. | 52°24′29″N 1°30′27″W |

| Dunstable, Bedfordshire |  | Priory Church of St Peter, Dunstable | proposed | An Augustinian house founded by 1125. Dissolved in 1540, the priory church was proposed by King Henry VIII as a cathedral for Bedfordshire.[92] Instead, the nave became a parish church.[93] | 51.886°N 0.5176°W |

| Guildford, Surrey |  | Holy Trinity Church, Guildford | 1927 – 1961 | A parish church, completed 1763, which was the pro-cathedral for the new Diocese of Guildford from its creation in 1927 from part of the Diocese of Winchester until the dedication of the new cathedral in 1961. | 51°14′09″N 0°34′15″W[94] |

| Guisborough, North Yorkshire |  | Priory Church of St Mary, Guisborough | proposed | This Augustinian priory of 1119 was dissolved in 1540. Its church was among those proposed as new cathedrals,[90] but it was mostly destroyed.[95] The Priory's name (Gisborough) differs slightly in spelling from that of the local town. | 54.535833°N 1.048889°W |

| Launceston, Cornwall | Priory Church of St Stephen | proposed | An Augustinian priory, founded in 1127 was dissolved in 1539. The priory church was proposed in 1540 as one possible cathedral for Cornwall,[90] but the site was sold.[96] | 50.636472°N 4.355417°W | |

| Leicester, Leicestershire |  | Abbey Church of St Mary de Pratis (St Mary of the Meadows) | proposed | An Augustinian house of 1143, the abbey was dissolved in 1538. The abbey church was listed among King Henry VIII's 1540 proposals as a cathedral for Leicestershire,[92] but the site had already been disposed of.[97] | 52.648683°N 1.136856°W |

| Liverpool, (Lancashire), Merseyside | .png.webp) | St Peter's Church, Liverpool | 1880–1919 | St Peter's church (shown) was built 1704, a second parish church for Liverpool. In 1880 the Diocese of Liverpool was created out of part of the Diocese of Chester, with St Peter's as its pro-cathedral. Building of a new cathedral began in 1904, opening 1919 when St Peter's was closed (demolished 1922). Its site is shown by a roadway marker (shown) in Church Street, Liverpool. | 53°24′18″N 2°59′03″W |

| Nottingham, Nottinghamshire |   | Church of St Mary the Virgin, Nottingham; status uncertain | proposed? | The original parish church of Nottingham, likely a 7th century foundation, listed in the Domesday Book, St Mary's current building dates from the 14th century. In the late 19th century the creation of a diocese for Nottinghamshire was considered, and St Mary's future elevation was seemingly widely assumed. Bodley installed a canopied chair (shown)[98] to be the new bishop's cathedra. The church's guide book[99] gives 1890 as the date of the chair's installation and of Bodley's internal Chapter House, despite Southwell Minster having been raised to cathedral status in 1884.[100] | 52.951111°N 1.143°W |

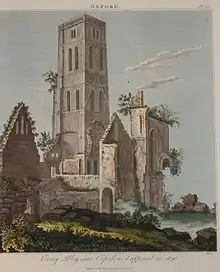

| Osney, Oxfordshire |  | Abbey Church of St Mary, Osney | 1542 – 1545 | An Augustinian priory founded in 1129, raised to abbey status c. 1154, but dissolved in 1539. Under 1540 proposals of King Henry VIII,[92] the abbey church became the cathedral for Oxfordshire in 1542, but was closed in 1545 and the see translated to Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford. Almost all traces at Osney have vanished. | 51°44′57″N 1°16′17″W |

| Shrewsbury, Shropshire |  .jpg.webp) | Abbey Church of St Peter & St Paul, Shrewsbury | proposed | A Benedictine abbey was founded in 1083 (on the site of the Anglo-Saxon church of St Peter), which was dissolved in 1539. In 1540 its church was proposed as a cathedral for Shropshire by King Henry VIII,[90] but the (truncated) nave alone survived as a parish church. The clerestory, lost after the dissolution, was rebuilt in the 19th century and in 1886-94 J L Pearson restored the whole east end (choir and sanctuary) that had also been lost. A 1922 proposal for cathedral status (for a new diocese) failed to get parliamentary approval. | 52°42′27″N 2°44′38″W |

| Southend-on-Sea, Essex |   | St Erkenwald's Church; status uncertain | proposed? | This was a very large[101] church built 1905–1910 to the design of Sir Walter Tapper, when Southend's population was growing rapidly. It seems that, due to its impressive size, "many influential people advocated the town as the diocesan centre for the new bishopric of Essex",[102] although Chelmsford had been chosen as the see for Essex in 1914. Declining post-war congregations in the 1950s and 1960s led to neglect and disrepair. The church was declared redundant in 1978, caught fire in 1992 and was demolished in 1995.[103] | 51°32′12″N 0°43′27″E |

| Waltham Abbey, Essex |   | Abbey Church of Waltham Holy Cross & St Lawrence | proposed | Built in the early 12th century on the site of 7th-century (and later) churches, this once-collegiate church served an Augustinian priory from 1177 (abbey from 1184, dissolved in 1540). It is the reputed burial-place of King Harold II, who was killed at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Proposed as a cathedral by King Henry VIII,[92] only the (truncated) nave[104] was saved as a parish church.[105] Extensive restoration took place in the 1860s and 1870s. | 51.6875°N 0.0035°W[106] |

| Welbeck, Nottinghamshire |

|

Abbey Church of St James the Great, Welbeck | proposed | A Premonstratensian abbey, founded 1140, was dissolved in 1538. Its church was proposed by King Henry VIII in 1540 as a possible cathedral for Nottinghamshire,[90] but the site was sold. The mansion later built on the site (shown) has traces of the former abbey. | refer53.262222°N 1.156111°W |

| Westminster, London |   | The Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster[107] | 1540 – 1550 (Diocese of Westminster); 1550 - 1556 (Diocese of London) | An abbey founded in the 7th century (later destroyed, and re-founded c. 959) the abbey was dissolved in 1540 but its church became one of King Henry VIII's new cathedrals,[92] for a new Diocese of Westminster. Cathedral status was lost when its diocese was reunited with London's in 1550. That status was briefly restored in 1552 (dated from 1550) when the church became a second cathedral for London (in addition to St Paul's),[108] but was finally lost in 1556 following the accession of Queen Mary I, who re-established it as a Benedictine monastery (dissolved 1559). The church became collegiate in 1560 but it is still universally known as Westminster Abbey. It is a Royal Peculiar. | 51°29′58″N 0°07′39″W |

Former Post-Reformation Roman Catholic cathedrals

| Location | Image | Name | Dates | Notes | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City of London, London |  | St Mary's Church, Moorfields | 1852–1869 | Built in 1820 to replace the church destroyed by the Gordon Riots, it became the first pro-cathedral of the Archdiocese of Westminster. That function was translated in 1869 to the church of Our Lady of Victories, Kensington. Demolished in 1900, the present St Mary's Church was opened in 1902.[109] | 51°31′7.64″N 0°5′8.57″W |

| Clifton, Bristol |  | Pro-Cathedral of the Holy Apostles | 1850–1973 | Building of a church started 1834, but unstable ground delayed completion (of a smaller church) until 1847. It became the pro-cathedral in 1850, and was closed in 1973 when it was replaced by the new Clifton Cathedral. Following a series of secular uses, the building was developed for housing and offices c. 2014. | 51.456297°N 2.609720°W |

| Hereford, Herefordshire |  | Abbey Church of St Michael and All Angels | 1854–1920 | The Diocese of Newport and Menevia was created in 1850 but with no official seat. In 1854 building began when it was agreed that this would be the pro-cathedral.[110] In 1859 it became a Benedictine priory, consecrated 1860. The see was translated to St David's Metropolitan Cathedral, Cardiff in 1920. It is now Belmont Abbey. | 52.03932°N 2.756412°W[111] |

| Kensington, London |  | Our Lady of Victories Church | 1869–1903 | It was the pro-cathedral for nearly thirty-six years until Westminster Cathedral in London was opened in 1903 | 51°29′57″N 0°11′52″W[112] |

| Liverpool, (Lancashire), Merseyside | Pro-Cathedral of St. Nicholas | 1850–1967 | Built in 1813, it was replaced by Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral in 1967. It was then a parish church for the Archdiocese of Liverpool until its demolition in 1973 to make way for Royal Mail's Copperas Hill Sorting Office, where a plaque records the site's former use. | 53°24′25″N 2°58′30″W[113] | |

| Middlesbrough, North Yorkshire | Cathedral Church of Our Lady Of Perpetual Succour | 1878–1983 | Opened in 1878 in the St Hilda's district to the north of Middlesbrough, it was the cathedral for the Diocese of Middlesbrough until the see was translated to the new St Mary's Cathedral in Coulby Newham, to the south of the town, in 1983. The former cathedral was left unused until 2000, when it was severely damaged in an arson attack and demolished. | 54°34′48″N 1°14′13″W | |

| Plymouth, Devon | Our Lady and St John the Evangelist Church | 1850–1858 | Known as St. Mary's Church, it opened on 20 December 1807 and was pro-cathedral for the Diocese of Plymouth from 1850 to 1858, when Plymouth Cathedral was opened. The church was then remodelled and given to the Little Sisters of the Poor. In 1884, they left and it was converted into housing. It was demolished in 1960.[114] | 50.3703°N 4.1593°W | |

| Southampton, Hampshire |  | St Joseph's Church | 1882 | It served as the pro-cathedral from May to August 1882, until the Cathedral of St John the Evangelist, Portsmouth was completed.[115] | 50.899072°N 1.405937°W |

| Southwark, London |  | Archbishop Amigo Jubilee Hall | 1942–1958 | It served as the pro-cathedral during the rebuilding of the adjacent cathedral following its destruction during World War II | 51.456297°N 2.609720°W |

| York, North Yorkshire |  | St. George's Church | 1850–1864 | It served as the pro-cathedral for the Diocese of Beverley until the construction of St. Wilfrid's in York. | 53.9550°N 1.0758°W[116] |

| York, North Yorkshire |  | St Wilfrid's Church | 1864–1878 | It succeeded St George's as pro-cathedral for the Diocese of Beverley until in 1878 the diocese was split into the Diocese of Leeds and the Diocese of Middlesbrough. | 53.961900°N 1.084700°W[117] |

Scotland

For various reasons,[118] formal dioceses were formed later in Scotland than in the rest of Great Britain. Bishops certainly existed in areas from the earliest Christian times (often from Irish monastic missionary activity), but the territory over which an early (often monastic) bishop operated was ill-defined. Hence the term "bishop's church" is sometimes used for a seat used by an early bishop rather than the word "cathedral" which some expect to be attached to a formal diocese. Traditionally, the medieval Scottish diocesan system was held to have been largely created by the Norman-influenced King David I (reigned 1124–1153) , though this is an oversimplification.

Nevertheless, in this List, the large number of pre-Reformation cathedrals in Scotland has been split into two sections in an attempt to make the information more manageable. The first section comprises cathedrals founded before 1100; the second, those cathedrals founded (or proposed) between 1100 and 1560. The choice of the year 1100, though arbitrary, approximates to the beginning of the reign of King David I (1124) (see above) and is also close to the date of the Norman Conquest (1066) which has been used to separate the two sections of pre-Reformation cathedrals in the portion of this List covering England.

In order to assist users of this List to trace the development of the dioceses, the text of most entries is preceded by the name (in parentheses) of the late medieval Scottish diocese[119] into which each early cathedral merged, usually by a process of translation of the see to a new location.

As the Scottish Reformation of 1560 developed, bishops and cathedrals became progressively marginalised and neglected. By Act of the Scottish Parliament in 1690 (confirming the Church's own final decision of 1689), the Church of Scotland finally became wholly Presbyterian, with no dioceses, no bishops, so no functioning cathedrals. At that date, all cathedrals of the Church of Scotland became former cathedrals. Some still use the title, but for honorific purposes only.

The Scottish Episcopal Church and the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland maintain their own diocesan structures with their own cathedrals and bishops.

Former cathedrals founded before 1100

survivors becoming Church of Scotland at the Scottish Reformation (1560)

| Location | Image | Name | Dates | Notes | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abercorn, West Lothian |   |

Abercorn Kirk; original dedication unknown | 681–685 | St Wilfrid founded a monastery here c. 675 at the (then) northern edge of Northumbria. In 681 St Trumwine became "Bishop of those Picts subject to English rule",[120] but when the Northumbrians lost the Battle of Nechtansmere in 685 he left.[121] The church (shown), likely occupying the monastic site, dates from the 12th century but was much altered in 1579 and 1893.[122] | 55.99334°N 3.47326°W[123] |

| Abernethy, (Perthshire), Perth and Kinross |  | status uncertain; site uncertain; dedication uncertain | early 8th century – 11th century? | (Diocese of Dunblane) The history of a supposed bishopric here is obscure. No bishops' names are known for certain, but Fergus may have been one of three during the early 8th century.[124] Any bishopric had moved to Muthill by the 12th century. The original church of St Brigid, said to be 6th century, may have been a bishop's church. | 56.333143°N 3.311670°W[125] |

| Birsay, Orkney |   | St Magnus' Kirk[126] | ?mid-11th century – 1137? | (Diocese of Orkney) It has been said that the original church here, dedicated as Christ's Church or Christchurch, was built by Earl Thorfinn in c. 1060, and used by several early bishops.[127] The extant kirk was built in 1664 (since enlarged) on the original site. | 59.129444°N 3.316389°W |

| Dunkeld, (Perthshire), Perth and Kinross |

| Cathedral of St Columba[128] | 9th century c. 1120 – 1689 | (Diocese of Dunkeld) Tradition tells of a monastery founded by the early 7th century after a visit by St Columba from Iona. By the 9th century the site had a stone-built Culdee monastery with relics of the saint. In c. 869 Dunkeld's abbot was described as the chief bishop of the kingdom,[129] but very soon after St Andrews became the chief bishopric of the Scottish church. The cathedral was re-founded in the 12th century, though most surviving fabric dates from the 15th century (there are traces of Culdee stonework). In the Reformation the nave was unroofed, but the 13th-century choir has been used ever since as the parish kirk. The cathedral ruins (but not the choir) are in the care of Historic Environment Scotland. | 56°33′54″N 3°35′23″W |

| Halkirk, (Caithness), Highland |  | Halkirk Auld Kirk; original dedication uncertain | early 8th century?; mid-12th century - early 13th century | (Diocese of Caithness) Tradition says St Ferus founded a church here in the early 8th century, before Caithness fell under Norse control. In c. 1145 King David I founded a bisopric here[130] despite Norse opposition. The second bishop was attacked and mutilated in 1202, the third murdered in 1222. King Alexander II sent a raiding party to avenge the bishop's murder, and he initiated the translation of the see in 1224 to Dornoch.[131] The former Halkirk cathedral became a parish church, rebuilt (on the same site) in 1753. It was declared redundant in 1934 (shown). No pre-1753 remains are known. | 58.5169°N 3.4863°W |

| Hoddom, (Dumfriesshire), Dumfries and Galloway | dedication unknown | late 6th century | A cathedral was said to have been founded here in the late 6th century by St Mungo.[132] Any cathedral seems not to have survived his death in 612, but a monastery had developed by the 8th century.[133] A parish church was built on the site in the 12th century, replaced after the Reformation by a new kirk of 1609 nearer to Ecclefechan at Hoddom Cross (burnt down in 1975). The co-ordinates given are for the former monastic site. | 55.041563°N 3.305430°W | |

| Iona, (Argyll), Argyll and Bute |

| St Mary's Cathedral | 6th century - 10th century (discontinuous); c. 1510 - 1638; 1662 - 1689 | (Diocese of the Isles) St Columba founded a monastery here c. 565. Like Columba, some abbots were also titled 'bishop'[134] but the abbey church did not achieve settled cathedral status until c.1510 when the see of the diocese was translated from Snizort Cathedral at Skeabost on Skye.[135] Attempts had been made in 1433 and 1498[136] to move the see to Iona,[137] and the diocese was governed in practice for some of that time from Iona. After bishoprics were abolished in 1689 the building fell into decay until rescued in 1899 by the creation of the Iona Cathedral Trust[138] and rebuilt by the Iona Community from 1938. In 2021 Historic Environment Scotland took over the care of parts of the abbey site. | 56.326127°N 6.400438°W |

| Kingarth, Isle of Bute, (County of Bute), Argyll and Bute |  | St Blane's Church, Kingarth | 6th century | A monastic bishopric was reputedly founded here by Saint Cathan who was succeeded as bishop by his nephew Saint Blane. It was a cathedral until St Blane's death c. 590. The monastery was destroyed by Vikings c. 790. A new church was built on the site in the 12th century, but fell out of use after 1560. Ruins (shown) are in the care of Historic Environment Scotland.[139] | 55.75°N 5.03°W |

| Lismore, (Argyll), Argyll and Bute |  | Lismore Kirk; cathedral probably dedicated to St Moluag | 6th century; and c. 1200 – c. 1560 | (Diocese of Argyll) The island of Lismore was by tradition chosen by St Moluag in the 6th century for a monastery. It again became the seat of a bishop in the 12th century when the Diocese of Argyll was created from the western portion of the Diocese of Dunkeld. The 14th-century cathedral was small and simple, and the new diocese poor, leading to proposals to translate the see to Saddell (which failed). The building was abandoned after the Reformation; it was roofless by 1679,[140] the tower and nave later razed (outlines can be seen). The choir was restored to be used as the parish kirk. | 56°32′4″N 5°28′50″W |

| Mortlach, (now Dufftown), (Banffshire), Moray |

| Mortlach Parish Church | 1011 to 1132 | Supposedly the site of a monastery founded by St Moluag in a mission to the Picts in c. 564, the Chronicle of John of Fordun records that in c. 1011 a bishopric was established here, aided by King Malcolm II. The standard account holds that this bishopric was translated to Aberdeen in 1132, but Woolf[141] proposes that the Mortlach bishopric was part of an earlier episcopal framework that was replaced by the creation of the Aberdeen diocese in a new diocesan system. Mortlach was renamed Dufftown in 1817. It is claimed that the parish church stands on the early monastic site[142] and contains some ancient fabric.[143][140] | 57.44078°N 3.12613°W |

| Rosemarkie, (Ross), Highland |  | Cathedral of St Peter [144] | early 8th century; and 1124 - mid-13th century | (Diocese of Ross) A monastic cathedral was probably founded by St Curetán[145] as abbot and first bishop in c. 700, and St Moluag was probably buried here.[144] The Diocese of Ross[146] was re-established by King David I in 1124. Remains of Curetán's church have been found and placed in the current parish kirk, built in 1821 on the same site. In the mid-13th century, Fortrose Cathedral was built nearby, and the see was translated there. | 57.59162°N 4.11516°W |

| St Andrews, Fife |  | Church of St Regulus (or St Rule) | c. 1070[147] – early 14th century | (Archdiocese of St Andrews (from 1472); formerly Diocese of St Andrews) The church is named for a legendary 4th-century Greek monk who allegedly brought St Andrew's relics to Scotland. They probably came from Bishop Acca[148][149] in the 730s, arriving at Kilrymont, a place later called St Andrews. A Culdee monastery there, later known as the Church of St Mary on the Rock, may have housed them[150] until they were enshrined in a cathedral. The Church of St Regulus, the first cathedral known here, was built maybe c. 1070.[151] Bishops of St Andrews, the chief centre of the Scottish church by the mid-9th century,[137] are, however, recorded from c. 1028.[152] Strongly built of squared ashlar blocks as a tower and chancel, it had a nave added to the west and a probable presbytery to the east c. 1144 when it became an Augustinian cathedral priory. The original tower and (unroofed) chancel stand in the precincts of the later St Andrews Cathedral, all in the care of Historic Environment Scotland. | 56.33965°N 2.786383°W |

| Whithorn, (Wigtownshire), Dumfries and Galloway | The Candida Casa, dedicated to St Martin of Tours[153] | late 4th century – early 9th century | Tradition tells that in c. 397 Saint Ninian,[154] a local Briton abbot and bishop, founded a monastery here with a (probably whitewashed-stone) church named the Candida Casa ("White House"). In time the name became attached to the place (Whithorn). The cathedral and monastery came under Northumbrian control in 731, but Its list of bishops ended early in the 9th century[155] when that control (and protection) ceased. Excavations at the site 1984–1996 found the location of Candida Casa, just outside and southeast of the boundary wall of the 1177 Priory site, and markers have been placed tracing the outline of the cathedral as in c. 730.[156] The Priory site is in the care of Historic Environment Scotland. | 54.733189°N 4.417525°W | |

Former cathedrals founded (or proposed) between 1100 and 1560

survivors becoming Church of Scotland at the Scottish Reformation (1560)

| Location | Image | Name | Dates | Notes | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire |

|

Cathedral of St Machar[157] | 1131–1689 | (Diocese of Aberdeen) Legend tells of a church founded c. 580 by St Machar in Old Aberdeen. In the 12th century a Norman cathedral was built (same dedication) and King David I had the see translated from Mortlach (now Dufftown) in 1132, during the episcopacy of Bishop Nechtan. The central tower fell in 1688, destroying the transepts, the remains of which are in the care of Historic Environment Scotland.[158] Since 1689 the nave with its twin spired towers has been used as the Church of Scotland's High Kirk of Aberdeen. | 57.169700°N 2.102069°W[159] |

| Birnie, Elgin, Moray |  | Birnie Parish Church[160] Claim of dedication to St Brendan[130] is "doubtful".[161] | c. 1140–1184 | (Diocese of Moray) The first bishop, Gregory, probably used this church, built c. 1140 on the site of an earlier church, as his cathedral. The see moved to Kinneddar in 1184. The building remains the parish kirk. | 57°36′41″N 3°19′48″W[162] |

| Brechin, Angus |  | Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, Brechin[130] | c.1150-1689 | (Diocese of Brechin) Originally a Culdee monastery, possibly derived from Abernethy. Here too is a fine round tower, dating from c. 1000. The first bishop, Samson, was appointed by David I in c. 1150.[163] The cathedral building, dating from the 13th century, was in use until November 2021 as Brechin High Kirk. | 56.730694°N 2.662125°W |

| Dornoch, (Sutherland), Highland |

|

Cathedral of St Mary[130] | 1239 – 1689 | (Diocese of Caithness) Founded in 1224 by (Saint)Gilbert de Moravia ("of Moray"), the fourth bishop, the see was translated here from Halkirk in 1239 when the remains of Adam, the third bishop, were moved here from Skinnet church, where they had been buried after his murder at Hallkirk in 1222. | 57.880729°N 4.030695°W[164] |

| Egilsay, Orkney |

|

St. Magnus' Church; status uncertain | probably sometime after 1135 | It seems unlikely that this island church ever was a cathedral for the Bishop of Orkney, but "it may have been regarded as a bishop's church".[165] The ruined mid-12th-century church commemorates the killing of St Magnus by his brother c. 1118, and is usually dated decades later than 1135 when Magnus was sainted. He spent the night before his murder in a church on Egilsay,[166] its site probably reused for this church. His body was buried on Egilsay, reburied at Birsay, and finally moved to Kirkwall. Unused since the early 19th century, the church (now unroofed with its round tower, unique in Orkney, reduced in height) is in the care of Historic Environment Scotland. | 59.1569°N 2.9353°W |

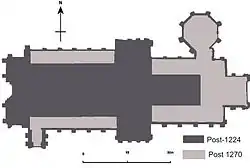

| Elgin, Moray |

| Cathedral of the Holy Trinity[167] | 1224 – c. 1560 | (Diocese of Moray) Building began in 1224 when Bishop Andrew got papal permission to move the see from Spynie to Elgin. It was rebuilt, enlarged, and a Chapter House added after a 1270 fire.[167] More rebuilding followed a fire in 1390 (after an attack by Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan) and still more in the 15th century. At the Reformation the cathedral was totally abandoned in favour of the 12th-century parish kirk of St Giles. Extensive ruins are in the care of Historic Environment Scotland. | 57°39′02″N 03°18′20″W |

| Fortrose, (Ross), Highland |   | Cathedral of Saint Peter and Saint Boniface[167][168]) | mid-13th century – mid-17th century | (Diocese of Ross) The see was moved here in the first half of the 13th century from Rosemarkie to a new sandstone building consisting of a rectangular nave and choir, with an external NW tower and NE sacristy-cum-chapter house. A SW aisle and chapel were added in the 14th century.[167] Ruins of the last two parts remain. Religious use of the building may have continued for a time after the 1560 Reformation, but before c. 1650[169] it had been used as the burgh's town hall and prison. The ruins are in the care of Historic Environment Scotland.[170] | 57.580885°N 4.130495°W |

| Glasgow |    | St. Mungo's Cathedral, Glasgow[167] | c. 1114 – 1689 | (Archdiocese of Glasgow (from 1492); formerly Ddiocese of Glasgow) Tradition has a church settlement founded here by St Mungo (also known as St Kentigern) in the 6th century, from which Glasgow developed. The diocese began with the appointment of Bishop John in c. 1114; suggested earlier bishops were not Glasgow-based.[167][171][172] The building is mostly 13th-century, the central tower and spire are 15th-century, and the Blackadder Aisle is c.1500. Its good and complete condition is at least partly due to the fact that, unlike most other Scottish pre-Reformation cathedrals, it was never unroofed. St Mungo's tomb is in the crypt. The building, (the High Kirk of Glasgow since 1689), is owned by the Crown and maintained by Historic Environment Scotland. | 55.862966°N 4.234436°W |

| Kinneddar, Moray |

| Kirk of Kinneddar; dedication unknown | c. 1187 – c. 1208 | (Diocese of Moray) Shortly after 1184 the seat of the Bishop of Moray was moved from Birnie to Kinneddar.[173] Kinneddar Castle, adjacent to the new cathedral, became a residence of the bishop from 1187 until the late 14th century: now hardly a trace remains. The see was moved again c. 1208 to Spynie by Bishop Bricus (1203–1222).[174] Following the Reformation the former cathedral here was abandoned in favour of a new kirk at Drainie when parishes were merged c. 1669. Surveys have confirmed that a mound in the old churchyard at Kinneddar (shown), used for later burials, covers the former cathedral's foundations. | 57.709451°N 3.305645°W |

| Kirkwall, Orkney |

| Cathedral of St Magnus[175] | 1137 – 1689 | (Diocese of Orkney) In 1135 the bones of the newly sainted Magnus (murdered on Egilsay c. 1118) were moved from the cathedral at Birsay to the church of St Olaf near Kirkwall.[176] Building of a cathedral here in 1137, dedicated to St Magnus, was instigated by St Ronald of Orkney and Bishop William. Consecration of the cathedral, with the translation of St Magnus' relics, probably took place before 1151.[177] Further building was done during the next four centuries.[140] Restorations in the 19th and 20th led to the finding of supposed relics of St Ronald and St Magnus were found[178] in pillars in the choir, the oldest part of the cathedral. The building houses a congregation of the Church of Scotland, but under a 1486 Charter[179] it is owned by the town of Kirkwall. | 58°58′56″N 2°57′32″W |

| Madderty, (Perthshire), Perth and Kinross |

|

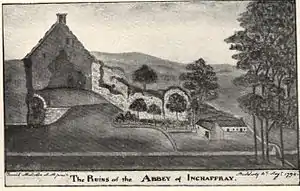

Inchaffray Abbey Church of the Virgin Mary and St John the Evangelist | proposed | In c. 1200 Gilbert, Earl of Strathearn, founded an Augustinian priory on a site which already had a church (dedicated to St John) and "a group of ecclesiastics known . . . as 'brethren'",[180] probably Culdees. The priory became an abbey c. 1220. By c. 1230 Dunblane Cathedral was roofless and had few staff[181] so in 1237 it was proposed that the see of Dunblane be transferred to Inchaffray. However, Bishop Clement of Dunblane resolved the situation and the proposal was abandoned. For some time the abbey remained large and relatively well-off, but by the time of the Scottish Reformation in 1560, it was among the poorest.[182] A few ruins remain on farmland (shown). | 56.3836°N 3.6954°W |

| Muthill, (Perthshire), Perth and Kinross |  | dedication unknown | mid - late 12th century | (Diocese of Dunblane) Culdees were here in the 12th century[140][183] when Muthill ecclesiastically superseded Abernethy. The bishops based here often took the title "Bishop of Strathearn". They had moved to Dunblane by the 13th century, leaving their cathedral here, with its distinctive tower, as a parish church. Enlarged in the 15th century, it was later abandoned for a new kirk built 1826–28.[184] It is now in the care of Historic Environment Scotland. | 56.326164°N 3.832428°W |

| Saddell, Kintyre, (Argyll), Argyll and Bute |

|

Saddell Abbey (conventual church dedicated to the Virgin Mary)[185] | proposed | A Cistercian monastery founded in 1160,[186] probably completed c. 1210. In 1249 it was proposed that the seat of the Bishop of Argyll should move here from Lismore Cathedral because of the latter's then ruinous state but no transfer took place. By the late 15th century the abbey had declined and was abandoned. In 1507 King James IV transferred the abbey's lands to the Bishop of Argyll who built a residence here[187] using Abbey stone. In 1512 James IV tried to have the see of Argyll moved to Saddell, but his death in 1513 ended negotiations. The site eventually became a graveyard among the few Abbey ruins that remained (shown). | 55.531944°N 5.511389°W |

| St Andrews, Fife |    | Cathedral Priory of St Andrews | 1318 - 1689 (in ruins from 1561) | (Archdiocese of St Andrews (from 1472); formerly Diocese of St Andrews) Founded c. 1160 by Bishop Ærnald (or Arnold),[188] as the much larger successor to the Augustinian priory formerly based at the Church of St Regulus (as the first cathedral). The building suffered a mishap in c. 1270 but was finally consecrated in 1318. A fire in 1378 caused serious damage, which was not fully repaired until 1440. Nonetheless, the cathedral was the largest, and the bishop/archbishop the most powerful, in Scotland. The Scottish Reformation changed everything: in 1559 a mob destroyed the interior of the cathedral, and by 1561 it had become an abandoned ruin being robbed of its stonework. The cathedral priory site and building remains, including those of the church of St Regulus, are in the care of Historic Environment Scotland. | 56.3400°N 2.7875°W |

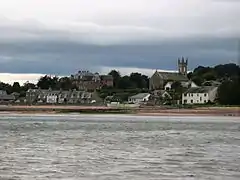

| Skeabost (Skye), (Inverness-shire), Highland |  | Snizort Cathedral; dedicated to St Columba[189] | 1387 - c. 1510 | (Diocese of the Isles) The original territory of this diocese was 'Sodor'[190] comprising the Hebrides and the Isle of Man, which had been settled by Vikings from c.850, and were under Norwegian suzerainty with a local ruler.[191] By a 1266 treaty Scotland took Sodor from Norway. The cathedral for the diocese was at Peel until 1387 when England began to take control of the Isle of Man. The diocese split,[192] and all but the Isle of Man[193] became the Scottish Diocese of the Isles, with an existing, possibly collegiate,[194] church on St Columba's Isle in the River Snizort, on Skye chosen as the seat for its bishop.[195] Attempts in 1433 and 1498[196] to move the see officially to the preferred location of Iona,[197] only succeeded c. 1510. The former cathedral's site[198] lies to the east on St Columba's Isle, with later ruins and burials nearby. | 57.4532°N 6.3057°W |

| Spynie, Elgin, Moray | Holy Trinity Cathedral | c. 1208 – 1224 | (Diocese of Moray) The see of the Bishop of Moray was translated from Kinneddar to a late 12th-century church here c. 1208. Bishops Richard (1187–1203) and Bricius (1203–1222) are buried here. Bishop Andrew (1223–1242), with the consent of Pope Honorius III, had the see translated to Elgin in 1224.[199] The former cathedral remained a parish church until c. 1735, when a new kirk was erected in the same parish, at New Spynie (or Quarrywood). Some stonework was reused in the new building, though much of the old church must have remained in situ, as a gable was reported falling from it in 1850. By 1962 only a slight mound in its graveyard marked the location of the former cathedral, the foundations of which had been measured at about 74 feet by 35 feet (22.2m x 10.5m). The site lies c. 500 m across a field SSW from the ruined Spynie Palace, a residence of the bishops of Moray from the late 12th century to 1689 (with some interruptions after 1560). The palace ruins are in the care of Historic Environment Scotland. | 57.672551°N 3.294929°W | |

| Thurso, (Caithness), Highland |

| Old St Peter's Kirk; status uncertain | possibly 12th century - possibly 16th century | This ruinous former parish kirk may have originated as a mainland outpost for the Norse bishopric of Orkney as evidence points to an early 12th century origin.[200] With the founding of a separate Diocese of Caithness in c. 1150, "it may have acted as a proto-cathedral for the diocese".[201] Records show further episcopal use of St Peter's as "throughout much of the 17th century the Diocesan Synod met alternately at Dornoch and Thurso",[202] Dornoch Cathedral having been rendered ruinous in 1570. When episcopacy ended in 1689, St Peter's became the parish kirk. By 1828 the structure was poor[203] so in 1832 it was abandoned in favour of a new kirk built nearer the town centre. The site is owned by Highland Council. Access is not normally possible. | 58.596575°N 3.515042°W |

| Whithorn, (Wigtownshire), Dumfries and Galloway |  | Cathedral of St Martin of Tours and St Ninian | 1128 – 1689 | (Diocese of Galloway) The see of Whithorn was refounded[204] in 1128 as an Augustinian cathedral priory, becoming Premonstratensian in 1177. The bishopric lay within the English (pre-Reformation) Province of York until 1472; afterwards in the Archdiocese of St Andrews until 1492, then in the Archdiocese of Glasgow. After 1560 parts of the cathedral fell into disrepair. From 1690 the nave (only) became the parish kirk. In the early 18th century the main tower collapsed. In 1822 a new parish kirk[205] was built nearby and much of the old monastic site was cleared for burials. The roofless nave of the cathedral and the crypt remain, in the care of Historic Environment Scotland. | 54.733500°N 4.417389°W |

Former Post-Reformation cathedrals

During and after the Scottish Reformation (1560) cathedrals were increasingly neglected and abandoned, but episcopacy continued to be supported by Stuart Kings. By Act of the Scottish Parliament in 1690 (confirming the Church's own final decision of 1689) the Church of Scotland became wholly Presbyterian, with no dioceses, no bishops, so no cathedrals as such. At that date, all Church of Scotland cathedrals became former cathedrals. Some still use the title, but for honorific purposes only.

The Scottish Episcopal Church and the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland maintain their own diocesan structures with their own cathedrals and bishops, as do the Orthodox churches.

| Location | Image | Name | Dates | Notes | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edinburgh, Midlothian |

| St. Giles' Cathedral, Edinburgh | 1633–1638 and 1661–1689 | (Diocese of Edinburgh, created 1633 from part of the Archdiocese of St Andrews) Dating from the 12th century (collegiate from 1468), St Giles' Church was raised to cathedral status in 1633 by King Charles I for his Scottish coronation,[129] and as the seat of the Bishop of Edinburgh. When episcopacy was abolished in 1689 it became the High Kirk of Edinburgh. | 55.949524°N 3.190928°W[206] |

| Location | Image | Name | Dates | Notes | Co-ordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edinburgh, Midlothian |

| St Paul's Pro-Cathedral | early 19th century – 1879 | Built 1816–1818, the church soon after became the Pro-Cathedral for the Episcopal Diocese of Edinburgh until 1879 when the new St Mary's Cathedral was sufficiently complete. Dedicated to St Paul and St George since 1932, when the nearby church of St George was closed. | 55.956797°N 3.188558°W |

Former Post-Reformation Roman Catholic cathedrals

| Location | Image | Name | Dates | Notes | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayr, South Ayrshire |  | Good Shepherd Cathedral | 1961–2007 | In 1961, after the original cathedral in Dumfries burnt down, this 1957 parish church became the cathedral of the Diocese of Galloway. Owing to falling attendance, it closed in 2007 and the see was translated to St Margaret's, Ayr.[207] In 2010, work was undertaken to convert the former 1961 cathedral into flats. It is a category C listed building.[208] | 55.469842°N 4.599087°W |

| Dumfries, (Dumfriesshire), Dumfries and Galloway |  | St Andrew's Cathedral | 1878–1961 | Built 1815, the church became a cathedral in 1878 for the Diocese of Galloway with the restoration of the Scottish hierarchy. It burnt down in 1961, the see was translated to Ayr and a new church was built over the crypt of the former 1878 cathedral, the tower and spire of which survive.[209] | 55.068352°N 3.606584°W |

Wales

The end of Roman rule in Britain in the early 5th century left a Romano-British (later sometimes called "Celtic") church which became increasingly confined to the western parts of the island (principally modern Wales) as Angles, Saxons, and other invaders attacked and settled from the east. This church grew in size and influence in the west during the 6th and 7th centuries (a period sometimes characterised in Wales as "The Age of the Saints")[210][211] with the conversion of ruling families (and consequently their peoples). Among the clergy, the title of "bishop" was more frequently used[212] than later when large dioceses developed. The surviving evidence for most of these early bishoprics is now fragmentary and secondary at best, if not legendary. This list contains some better-evidenced examples.

The dioceses of the Welsh church, certainly from Norman times, were, sometimes reluctantly,[213] part of the English church in the Province of Canterbury. This situation continued after the establishment of the Church of England at the Reformation until 1920, when the Church of England was disestablished in Wales, becoming the Church in Wales, a separate self-governing member of the Anglican Communion.

Former cathedrals (or proposed cathedrals)

| Location | Image | Name | Dates | Notes | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carmarthen, Carmarthenshire |   | St Peter's Church, Carmarthen | proposed | In 1536 William Barlow, the newly appointed Bishop of St Davids, proposed to move the see to Carmarthen (then the most important town in Wales) which had just one parish church, St Peter's. The Cathedral Chapter opposed the bishop, and by 1539 it had finally defeated his proposal. A similar proposal in c. 1678 by Bishop Thomas also failed.[214] A Norman foundation, the existing building dates from the 14th century, with extensive mid-19th century restorations. | 51.858001°N 4.302713°W |

| Denbigh, Denbighshire |  | Leicester's Church, Denbigh (intended as St David's Church) | proposed | Generally known as Leicester's Church, this post-Reformation project was begun in 1578 by the Earl of Leicester. Planned as a large preaching hall it was intended to replace St Asaph Cathedral, but construction ceased in 1584. | 53.1823°N 3.4193°W |

| Glasbury, (Radnorshire), Powys | .jpg.webp) | site probable; original dedication unknown | 6th century – 11th century | Glasbury is the location of the 6th-century Clas Cynidr, supposedly founded by Saint Cynidr (otherwise Kenider). A list of bishops of Clas Cynidr survives,[215] but little remains to show the original site of the clas or its church, which lay south of the modern village (on the other side of the river). The river changed its course in the 17th century and left the church site isolated from the village by a new stretch of river, so it was abandoned. New churches were built in the village (in c. 1665, later demolished, and in 1838). The dedication of the parish church to St Peter probably dates from c. 1056 when the manor of Glasbury was granted to St Peter's Abbey. The coordinates relate to visible earthworks in a field where the clas church probably stood. | 52.04297°N 3.20246°W |

| Holyhead, Anglesey |  | St Cybi's Church | 540 – 554 or later | The much-travelled Saint-bishop Cybi (English: Cubby) settled here c. 540, founded a large and important clas, and remained its head until his death in 554. The site became known as Caergybi, meaning Cybi's fort, and this is the Welsh name for the town of Holyhead. The 13th-century chancel is the oldest part of the parish church, which stands on or near the ancient site.[216] | 53.3114°N 4.6326°W |

| Llanbadarn Fawr, Ceredigion |   | St Padarn's Church, Llanbadarn Fawr | 6th century – ?8th century; and proposed | Few facts are known about the early 6th-century bishop-saint Padarn, who reportedly founded an important clas here. Other bishops seem to have succeeded him, possibly until 720, after which the area came under the authority of St Davids. A long period of collegiate service followed[217] until it was made a vicarage under a rector in 1231, and the building of the present church began. In time it developed into today's large and important parish church. The 1920 reorganisation of the Church in Wales led to thoughts of cathedral status (so reducing the great extent of the Diocese of St David's), and the re-creation of an episcopal see at Llanbadarn, but instead the Diocese of Swansea and Brecon was created in 1923. | 52.409°N 4.061°W |

| Llandeilo, Carmarthenshire |  | St Teilo's Church, Llandeilo Fawr | 6th century – ?11th century | A clas was founded here, supposedly by the 6th-century abbot-bishop Saint Teilo. Several names are later recorded as bishops of Teilo, and even if some are doubtful[218] "the bishops of Teilo have impeccable 9th-century credentials".[219] Notes added to the Lichfield Gospels[220] record Bishop Nobis (or Nyfys) (872?–874). He, and Bishop Joseph (1022–1045), were both later spuriously claimed as early bishops of Llandaff.[221] The church was virtually rebuilt 1848–1850, and its 16th-century tower restored 1883.[222] | 51.88173°N 3.99285°W |

| Llanynys, Denbighshire |   | St Saeran's Church, Llanynys | 6th century? | Tradition tells that a 6th-century clas (and mother-church[223] for several villages) was founded by bishop-saint Saeran, who may have come from Ireland.[224] Alternatively, St Mor has been suggested as founder, with the church being merely the burial place of St Saeran.[225] Little is known about either saint. The church on the ancient site is double-naved: the western part of the north nave is 13th-century, the rest (apart from the 1544 porch) was built c. 1500. There is a 15th-century wall painting of St Christopher (shown). | 53.1536°N 3.3425°W |

| Rhuddlan, Denbighshire |  | proposed; site uncertain | In 1281 King Edward I and Anian II, Bishop of St Asaph, petitioned the Pope to approve the transfer of the see of St Asaph to a new, larger, fortified town being built (for English settlers) at Rhuddlan, due to the claimed remoteness and dangers of St Asaph. However, further territorial gains by the English led to the proposal's abandonment by 1283. The intended cathedral site was probably used for the new parish church, St Mary's, in c. 1300 (shown).[226] | 53.2907°N 3.4696°W | |

| St Asaph, (Llanelwy), Denbighshire | %253B_Church_of_St_Kentigern_and_St_Asa_%252C_St_Asaph%252C_North_Wales_14.JPG.webp) %253B_Church_of_St_Kentigern_and_St_Asa_%252C_St_Asaph%252C_North_Wales_20.JPG.webp) | Church of St Kentigern and St Asa; site probable; original dedication unknown | 6th century – ?11th century | According to his hagiographer,[227] a clas was founded by Saint Kentigern in c. 560 at Llanelwy ("sacred enclosure on the River Elwy"). He was succeeded as bishop by Saint Asaph (or Asaf/Asa), which led to Llanelwy being known (in English) as St Asaph.[228] The site of the original (wooden) cathedral is likely now occupied by the parish church (near the river) at the foot of the hill crowned by the Norman cathedral, with the re-establishment of the bishopric in 1143.[229] The parish church building dates from the 13th century. | 53.25705°N 3.44525°W |

The Seven Bishop-Houses of the Kingdom of Dyfed

Collections of medieval Welsh Law[230] record that the (early medieval) Kingdom of Dyfed had seven so-called "bishop-houses" (in Welsh, esgopty), following a general pattern of one bishop-house in each cantref.[230][231][232][233][234][235] Their role is not clear, but they must have been relatively important ecclesiastical sites (with St Davids having a higher status than any of the others). Apart from the Bishop of St Davids, their heads were described as abbots, not bishops.

Whether the other six were also bishoprics, former bishoprics, burial places of saint-bishops,[235] or staging posts in the travels of (say) the bishop of St Davids[236] is debated. They are included here on the basis that any and all of them may well have been the seat of a bishop at some time. Details of all seven bishop-houses are given below for the sake of completeness, although St Davids has never ceased to be the seat of a bishop. The status of a bishop-house, as distinct from that of a cathedral (St Davids), seems not to have survived the ending of the Kingdom of Dyfed (in 920), even less the arrival of the Normans.

The sites identified below may not be exactly the original sites of the bishop-houses (with the probable exception of Llandeilo Llwydarth): some minor relocation over the course of centuries cannot be ruled out.

| Location | Image | Medieval Placename (spellings may vary) | Pre-Norman Cantref (spellings may vary) | Notes | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St Davids, Pembrokeshire |  | Mynyw | Prebidiog | St Davids Cathedral has continued to be the seat of a bishop since its foundation in the 6th century. It is included here to complete the list of Dyfed's seven bishop-houses | 55.469842°N 4.599087°W |

| Carmarthen, Carmarthenshire | Llan Teulydawc | Gwarthaf | The Normans made the church a cell of Battle Abbey. Later, in c. 1125, the Bishop of St Davids founded here the Priory of St John the Evangelist and St Teulyddog with Augustinian Canons (dissolved 1536). The site was finally cleared c.1781 and put to industrial use. A late medieval gatehouse survives, converted for housing. | 51.860149°N 4.296345°W | |

| Clydau, Pembrokeshire |  | Llan Geneu | Emlyn | The 14th–15th-century parish church (shown) is dedicated to Saint Clydai but the medieval place-name clearly refers to Saint Ceneu. Restored in the late 19th century, the most original parts of the church are its tower and nave. It is sited centrally among the five hamlets it serves. | 51.99°N 4.5488°W |