List of space stations

A space station is a spacecraft capable of supporting a human crew in orbit for an extended period of time and is therefore a type of space habitat. It lacks major propulsion or landing systems. An orbital station or an orbital space station is an artificial satellite (i.e., a type of orbital spaceflight). Stations must have docking ports to allow other spacecraft to dock to transfer crew and supplies. The purpose of maintaining an orbital outpost varies depending on the program. Space stations have most often been launched for scientific purposes, but military launches have also occurred.

Space stations have harboured so far the only long-duration direct human presence in space. After the first station, Salyut 1 (1971), and the deaths of its Soyuz 11 crew, space stations have been operated consecutively since Skylab (1973), having allowed a progression of long-duration direct human presence in space. Stations have been occupied by consecutive crews since 1987 with the Salyut successor Mir. Uninterrupted occupation of stations has been achieved since the operational transition from the Mir to the ISS, with its first occupation in 2000.

The ISS has hosted the highest number of people in orbit at the same time, reaching 13 for the first time during the eleven day docking of STS-127 in 2009. On May 30, 2023 there were 11 people on the ISS and 6 on the China's Tiangong, making 17 people in orbit, record number as of 2023.[1]

As of 2023, there are two fully operational space stations in low Earth orbit (LEO) – the International Space Station (ISS) and China's Tiangong Space Station (TSS). The ISS has been permanently inhabited since October 2000 with the Expedition 1 crews and the TSS began continuous inhabitation with the Shenzhou 14 crews in June 2022. These stations are used to study the effects of spaceflight on the human body, as well as to provide a location to conduct a greater number and longer length of scientific studies than is possible on other space vehicles. In 2022, the TSS finished its phase 1 construction with the addition of two lab modules: Wentian ("Quest for the Heavens"), launched on 24 July 2022, and Mengtian ("Dreaming of the Heavens") launched on 31 October 2022, joining the ISS as the most recent space station operating in orbit. In July 2022, Russia announced intentions to withdraw from the ISS after 2024 in order to build its own space station.[2] There have been numerous decommissioned space stations, including the USSR's Salyuts, Russia's Mir, NASA's Skylab, and China's Tiangong 1 and Tiangong 2.Past stations

These stations have re-entered the atmosphere and disintegrated.

The Soviet Union ran two programs simultaneously in the 1970s, both of which were called Salyut publicly. The Long Duration Orbital Station (DOS) program was intended for scientific research into spaceflight. The Almaz program was a secret military program that tested space reconnaissance.[3]

‡ = Never crewed

| Name | Program Entity |

Crew size |

Launched | Reentered | Days in orbit |

Days occu- pied |

Total crew and visitors |

Number of crewed visits |

Number of robotic visits |

Mass (* = at launch) |

Pressurized volume |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salyut 1 | DOS[4] | 3[5] | 19 April 1971[6] | 11 October 1971[7] | 175 | 24[8] | 6[9] | 2[9] | 0[9] | 18,425 kg (40,620 lb)[6] | 100 m3 (3,500 cu ft)[10] |

| | |||||||||||

| DOS-2‡ | DOS[12] | —[lower-alpha 1] | 29 July 1972[6][13] | 29 July 1972 | failed to reach orbit | — | — | — | — | 18,000 kg (40,000 lb)[14] | — |

| | |||||||||||

| Salyut 2‡ | Almaz[13] | —[lower-alpha 1] | 3 April 1973[13] | 16 April 1973[13] | 13[13] | — | — | — | — | 18,500 kg (40,800 lb)[16] | — |

| | |||||||||||

| Kosmos 557‡ | DOS[18] | —[lower-alpha 1] | 11 May 1973[19] | 22 May 1973[20] | 11 | — | — | — | — | 19,400 kg (42,800 lb)[14] | — |

| | |||||||||||

| Skylab | Skylab[21] | 3[22] | 14 May 1973[23] | 11 July 1979[24] | 2249 | 171[25] | 9[26] | 3[27] | 0[28] | 77,088 kg (169,950 lb)[29] | 360 m3 (12,700 cu ft)[30] |

| Salyut 3 | Almaz[4] | 2[31] | 25 June 1974[32] | 24 January 1975[33] | 213 | 15[34] | 2[34] | 1[34] | 0 | 18,900 kg (41,700 lb)*[35] | 90 m3 (3,200 cu ft)[18] |

| | |||||||||||

| Salyut 4 | DOS[36] | 2[37] | 26 December 1974[38] | 3 February 1977[38] | 770[38] | 92[39] | 4[39] | 2[39][40] | 1[39] | 18,900 kg (41,700 lb)[18]* | 90 m3 (3,200 cu ft)[18] |

| | |||||||||||

| Salyut 5 | Almaz[36] | 2[41] | 22 June 1976[42] | 8 August 1977[43] | 412 | 67[44] | 4[44] | 3[44] | 0[44] | 19,000 kg (42,000 lb)[18]* | 100 m3 (3,500 cu ft)[18] |

| | |||||||||||

| Salyut 6 | DOS[36][45] | 2[46] | 29 September 1977[46] | 29 July 1982[47] | 1764 | 683[48] | 33[48] | 16[48] | 14[48] | 19,000 kg (42,000 lb)[49] | 90 m3 (3,200 cu ft)[50] |

| | |||||||||||

| Salyut 7 | DOS[36][45] | 3[51] | 19 April 1982[52] | 7 February 1991[52] | 3216[52] | 861[51] | 22[51] | 10[51] | 15[51] | 19,000 kg (42,000 lb)[53] | 90 m3 (3,200 cu ft)[18] |

| | |||||||||||

| Mir | DOS[36][45] | 3[54] | 19 February 1986[55][lower-alpha 2] | 23 March 2001[24][55] | 5511[55] | 4594[56] | 125[56] | 39[57] | 68[56] | 129,700 kg (285,900 lb)[58] | 350 m3 (12,400 cu ft)[59] |

| |||||||||||

| Tiangong-1 | Tiangong | 3[60] | 29 September 2011[61][62] | 2 April 2018[63] | 2377 | 22 | 6[64][65] | 2[64] | 1[66] | 8,506 kg (18,753 lb)[67] | 15 m3 (530 cu ft)[68] |

| Tiangong-2 | Tiangong | 2 | 15 September 2016 | 19 July 2019 | 1037 | 29 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8,506 kg (18,753 lb)[67] | 15 m3 (530 cu ft)[68] |

Prototypes

These stations are prototypes; they only exist as testing platforms and were never intended to be crewed. OPS 0855 was part of a cancelled Manned Orbiting Laboratory project by the United States, while the Genesis stations were launched privately. The Genesis stations were "retired" when their avionics systems stopped working after two and a half years, yet they still remain in orbit as derelict spacecraft.

| Name | Entity | Program | Launched | Reentered | Days in orbit | Mass | Pressurized volume |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPS 0855 | MOL | 3 November 1966[69] | 9 January 1967[69] | 67 | 9,680 kg (21,340 lb) | 11.3 m3 (400 cu ft) | |

| Genesis I | 12 July 2006[70] | (In Orbit) | 6316 | 1,360 kg (3,000 lb)[71] | 11.5 m3 (410 cu ft)[72] | ||

| Genesis II | 28 June 2007[70] | 5965 | 11.5 m3 (406 cu ft)[72] |

Operational stations

As of 2023, two stations are orbiting Earth with life support system in place and fully operational.

| Name | Entity | Crew size | Launched | Days in orbit[lower-alpha 3] | Days occupied |

Total crew and visitors |

Crewed visits |

Robotic visits |

Mass | Pressurized volume |

Habitable volume |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| International Space Station | 7[73] | 20 November 1998[73][lower-alpha 2] | 9107 | 8396[74] | 230[75] | 88 [76] | 94 [76] | 450,000 kg (990,000 lb)[77] | 1,005 m3 (35,500 cu ft)[78] | 388 m3 (13,700 cu ft) | |

| Tiangong space station | 3–6[79] | 29 April 2021 | 911 | 781 | 17 | 6 | 7 | 100,000 kg (220,000 lb) | 340 m3 (12,000 cu ft) | 122 m3 (4,310 cu ft) |

Planned and proposed

These space stations have been announced by their host entity and are currently in planning, development or production. The launch date listed here may change as more information becomes available.

| Name | Entity | Program | Crew size | Launch date | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lunar Gateway | Artemis | 4 |

November 2024[80][81] | Intended to serve as a science platform and as a staging area for the lunar landings of NASA's Artemis program and follow-on human mission to Mars. | |

| Axiom Station | International Space Station programme | TBD |

Late 2025[82] | Eventually will detach from the ISS in the early 2030s and form a private, free flying space station for commercial tourism and science activities. | |

| Russian Orbital Service Station (ROSS) |

Russia's next generation space station. | TBD |

2027[83] | With Russia leaving the ISS programme in 2024, Roscosmos announced this new space station in April 2021 as the replacement for that program. | |

| Starlab Space Station | Private | 4 |

2027[84] | "Commercial platform supporting a business designed to enable science, research, and manufacturing for customers around the world." | |

| Orbital Reef Station | Private | 10 |

second half 2020s[85] | "Commercial station in LEO for research, industrial, international, and commercial customers." | |

| ISRO Space Station[86] | Indian Human Spaceflight Programme | 3 |

~2035[87][88][89][90][91] | ISRO chairman K. Sivan announced in 2019 that India will not join the International Space Station, but will instead build a 20 ton space station of its own.[92] It is intended to be built 5–7 years after the conclusion of the Gaganyaan program.[93] | |

| Lunar Orbital Station[94] (LOS) |

TBD |

after 2030[95] | |||

| TBD | Private | 4–8[96] |

"to provide a base module for extended capabilities including science, tourism, industrial experimentation"[97] | ||

| Haven-1 | Private | 4 |

2025 [98] | "Scheduled to be the world's first commercial space station, Haven-1 and subsequent human spaceflight missions will accelerate access to space exploration"[99] | |

| LIFE Habitat Pathfinder | Private | TBD |

2026 | "Before offering LIFE for Orbital Reef, though, the company is proposing to launch a standalone “pathfinder” version of LIFE as soon as the end of 2026".[100] |

Cancelled projects

Most of these stations were canceled due to financial difficulties, or merged into other projects.

| Name | Entity | Crew | Cancellation | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manned Orbiting Laboratory 1–7 | 2[101] | 1969 | Boilerplate mission launched successfully, wider project cancelled due to excessive costs[102] | |

| Skylab B | 3[103] | 1976 | Constructed, but launch cancelled due to lack of funding.[104] Now a museum piece. | |

| OPS-4 | 3[105] | 1979 | Constructed, but Almaz program cancelled in favour of uncrewed recon satellites. | |

| Freedom | 14–16[106] | 1993 | Merged to form the basis of the International Space Station. | |

| Mir-2 | 2[107] | |||

| Columbus MTFF | 3 | |||

| Galaxy | Robotic[108] | 2007 | Canceled due to rising costs and ability to ground test key Galaxy subsystems[109] | |

| Sundancer | 3 | 2011 | Was under construction, but cancelled in favour of developing B330. | |

| Almaz commercial | 4+ | 2016 | Soviet hardware was acquired, but never launched due to lack of funds. | |

| Tiangong-3 | 3 | 2017 | The goals for Tiangong-2 and 3 were merged, and were completed by a single station rather than two separate stations. | |

| OPSEK | 2+ | 2017 | Some modules such as Nauka were launched and attached to the ISS- but proposals to split these off as a separate station were cancelled, and they instead remain part of the ISS. | |

| B330 | 3 | 2020 | Test articles were constructed but not flight ready hardware; cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. |

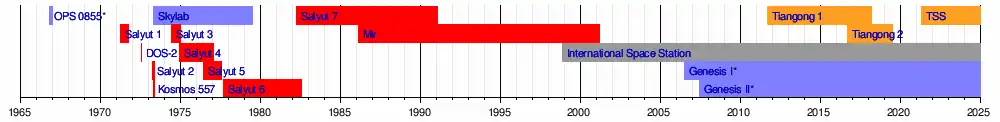

Timeline

Size comparison

See also

Notes

- The USSR intended to crew these stations with 2 men, however they re-entered the atmosphere before the cosmonauts were launched.

- Launch date of the initial module. Additional modules for this station were launched later.

- Correct as of 27 October 2023

References

- Clark, Stephen. "Chinese astronaut launch breaks record for most people in orbit – Spaceflight Now". Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- Chang, Kenneth; Nechepurenko, Ivan (2022-07-26). "Russia Says It Will Quit the International Space Station After 2024". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-07-26.

- "The Station: Russian Space History". PBS. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- Harland, David Michael (2005). The Story Of Space Station Mir. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 351. ISBN 978-0-387-73977-9.

- "Space Stations". ThinkQuest. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- "Salyut 1". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- Tony Long (19 April 2011). "April 19, 1971: Soviets Put First Space Station Into Orbit". Wired.

- "Space Station". World Almanac Education Group Inc. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- Vic Stathopoulos. "The first Space Station - Salyut 1". aerospaceguide.net. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- Gibbons, John H. (2008). Salyut: Soviet steps toward permanent human presence in space. DIANE Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4289-2401-7.

- "Salyut 1". Archived from the original on December 11, 2016. Retrieved 2021-07-17.

- Grujica S. Ivanovich (2008). Salyut - The First Space Station: Triumph and Tragedy. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 329. Bibcode:2008saly.book.....I. ISBN 978-0-387-73973-1.

- Zimmerman, Robert (2003). Leaving Earth. Washington, DC, United States: Joseph Henry Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-309-08548-9.

- "Salyut". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on June 2, 2002. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- "Salyut". Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved 2021-07-17.

- "Saylut 2". NASA. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- "Almaz". Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved 2021-07-17.

- D.S.F. Portree (1995). "Mir Hardware Heritage" (PDF). NASA Sti/Recon Technical Report N. 95: 23249. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2010. (Full text available on Wikisource)

- "NASA – NSSDC – Spacecraft – Trajectory Details". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- "Large Uncontrolled Reentries". planet4589.org. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- Harris, Phillip (2008). Space Enterprise: Living and Working Offworld in the 21st Century. Springer. p. 582. ISBN 978-0-387-77639-2.

- Collins, Martin, ed. (2007). After Sputnik: 50 Years of the Space Age. United States: Smithsonian Institution with Harper Collins Books. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-06-089781-9.

- "Skylab". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- Stewart Taggart (22 March 2001). "The Day the Sky(lab) Fell". Wired. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- "Skylab's Goals". Retrieved 2021-07-17.

- "Skylab 30 Years Later". Space Daily. 11 November 2003.

- Tony Long (11 July 2008). "July 11, 1979: Look Out Below! Here Comes Skylab!". Wired. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- Oberg, Jame (1992). "Skylab's Untimely Fate". Air & Space. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "BBC – Solar System – Skylab (pictures, video, facts & news)". BBC. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- Zimmerman, Robert (2003). Leaving Earth. Washington, DC, United States: Joseph Henry Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-309-08548-9.

- Furniss, Tim (2003). A History of Space Exploration: And Its Future... Lyons Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-58574-650-7.

- "Salyut-3 (OPS-2)". Russian Space Web. Archived from the original on 1 June 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Largest Objects to Reenter". Aerospace Corporation. Archived from the original on 1 February 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- "Resident Crews of Salyut 3". spacefacts.de. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Skylab". University of Oregon. Retrieved 31 January 2012. (Lecture at the University of Oregon, Salyut 3 is mentioned later in the lecture)

- Dudley-Rowley, Marilyn (2006). "The Mir Crew Safety Record: Implications for Space Colonization". Space 2006. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. p. 2. doi:10.2514/6.2006-7489. ISBN 978-1-62410-049-9.

- "Salyut 4". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on June 2, 2002. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Salyut-4". Aerospaceguide. Archived from the original on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "The DOS Space Stations: Salyut 4". Zarya.info. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Spaceflight :Soviet Space Stations". Centennial of Flight. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- "Soyuz 21". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on August 27, 2002. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "OPS-3 (Salyut-5) space station". Russian Space Web. Archived from the original on 4 June 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Sixth Salyut Space Station Launched". Science News. 112 (15): 229. 1977. doi:10.2307/3962473. JSTOR 3962472. (requires JSTOR access)

- "Salyut 5". Aerospaceguide. Archived from the original on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- Grujica S. Ivanovich (2008). Salyut - The First Space Station: Triumph and Tragedy. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 358. Bibcode:2008saly.book.....I. ISBN 978-0-387-73973-1.

- "Salyut 6". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- Robert Christy. "The DOS Space Stations: Expedition 5 (1981) and The End". Zarya. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Salyut 6". Aerospaceguide. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Salyut 6 (craft information)". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on August 23, 2002. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Salyut 6". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 1 June 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Salyut 7". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on August 23, 2002. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Summary of Recovered Reentry Debris". Aerospace Corporation. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- "Salyut 7". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- Seth Borenstein (16 November 1995). "Atlantis' Astronauts Bear Gifts To Mir Crew". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- Tony Long (19 February 2008). "Feb. 19, 1986: Mir, the Little Space Station That Could". Wired. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- "Mir Space Station". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Mir". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 23 December 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Space Station Mir". SpaceStationInfo. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- Macatangay, Ariel V.; Perry, Ray L. "Cabin Air Quality On Board Mir and the International Space Station—A Comparison" (PDF). International Conference on Environmental Systems. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- Stephen Clark. "Chinese rocket successfully launches mini-space lab". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- Ken Kremer (29 September 2011). "China Blasts First Space Lab Tiangong 1 to Orbit". universetoday.com.

- "China Successfully Launches 1st Space Lab Module". Arabia 2000. 29 September 2011.

- Kuo, Lily (2018-04-02). "Tiangong-1 crash: Chinese space station comes down in Pacific Ocean". The Guardian.

- Amos, Jonathan (2012-06-18). "Shenzhou 9 Docks with Tiangong 1". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- Shenzhou 10#Crew

- Amos, Jonathan (2 November 2011). "Chinese spacecraft dock in orbit". BBC News. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- "Tiangong". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on October 3, 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- "Chinese Space Program | Tiangong 1 | SinoDefence.com". SinoDefence.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- "Directory of U.S. Military Rockets and Missiles". Designation Systems. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- "The Dnpur launcher". Russian Space Web. Archived from the original on 24 June 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- Alan Boyle (17 April 2007). "Private space station test delayed till May". NBC News. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- Tariq Malik and Leonard David. "Bigelow's Second Orbital Module Launches Into Space". Space.com. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "International Space Station, ISS Information, Space Station Facts, News, Photos – National Geographic". National Geographic. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- "Facts and Figures". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Facts and Figures". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 28 April 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- "A timeline of ISS missions". Russian Space Web. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- "The International Space Station". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- Public Broadcasting Station (28 April 2016). "Space Station | FYI | ISS Fact Sheet". PBS. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- Lutz, Eleanor (2021-09-22). "A Tour of China's Future Tiangong Space Station". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-10-10.

- "NASA, Northrop Grumman Finalize Moon Outpost Living Quarters Contract". NASA (Press release). 9 July 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- "Report No. IG-21-004: NASA's Management of the Gateway Program for Artemis Missions" (PDF). OIG. NASA. 10 November 2020. pp. 5–7. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- Foust, Jeff (14 October 2022). "Commercial space station developers seek clarity on regulations". SpaceNews.

- "Russia to set up national orbital outpost in 2027 — Roscosmos". TASS. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- "Starlab - the first ever free-flying commercial space station".

- "Blue Origin andn Sierra Space Developing Commercial Space Station" (PDF). Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- "Prime Minister reviews readiness of Gaganyaan Mission".

- "Prime Minister reviews readiness of Gaganyaan Mission".

- "India plans to launch space station by 2030". Engadget. June 16, 2019. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- "ISRO Looks Beyond Manned Mission; Gaganyaan Aims to Include Women".

- "India eying an indigenous station in space". The Hindu Business Line. June 13, 2019. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- "ISRO Chairman announces details of Gaganyaan, Chandrayaan-2 and Missions to Sun& Venus India to have its own space station, says Dr K Sivan". Press Information Bureau. 13 June 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- "India planning to have own space station: ISRO chief". The Economic Times.

- "India's own space station to come up in 5–7 years: Isro chief – Times of India". The Times of India. 13 June 2019. Retrieved 2019-06-13.

- Ahatoly Zak. "Lunar Orbital Station, LOS". Russian Space Web. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- Xinhua (28 April 2012). "Russia unveils space plan beyond 2030". english.cntv.cn. China Central Television. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "Northrop Grumman Signs Agreement with NASA to Design Space Station for Low Earth Orbit".

- "NASA Selects Companies to Develop Commercial Destinations in Space". 2 December 2021.

- Etherington, Darrell (2023-05-10). "Vast and SpaceX aim to put the first commercial space station in orbit in 2025". TechCrunch. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- "VAST Announces the Haven-1 and VAST-1 Missions. — VAST". www.vastspace.com. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- Foust, Jeff (2023-06-28). "Sierra Space describes long-term plans for Dream Chaser and inflatable modules". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2023-07-12.

- Collins, Martin, ed. (2007). After Sputnik: 50 Years of the Space Age. New York: Smithsonian Institution in association with Harper-Collins Publishers. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-06-089781-9.

- "Spaceflight :The International Space Station and Its Predecessors". centennialofflight.net. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- Shayler, David; Burgess, Colin (2007). NASA'S scientist-astronauts. Springer. p. 280. Bibcode:2006nasa.book.....S. ISBN 978-0-387-21897-7.

- astronautix.com. "Skylab B". astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- "Almaz".

- "Space Station Freedom". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- "ISS Elements: Service Module ("Zvezda")". spaceref.com. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- Dan Cohen. "Developing a Galaxy". Bigelow Aerospace, LLC. Archived from the original on 18 December 2007. Retrieved 23 November 2007. (page has been taken down, link is to an archived version)

- SPACE.com Staff. "Bigelow Aerospace Fast-Tracks Manned Spacecraft | Space.com". space.com. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

External links

Media related to Space stations at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Space stations at Wikimedia Commons