Live in Cook County Jail

Live in Cook County Jail is a 1971 live album by American blues musician B.B. King, recorded on September 10, 1970, in Cook County Jail in Chicago. Agreeing to a request by jail warden Winston Moore, King and his band performed for an audience of 2,117 prisoners, most of whom were young black men. King's set list consisted mostly of slow blues songs, which had been hits earlier in his career. When King told ABC Records about the upcoming performance, he was advised to bring along press and recording equipment.

| Live in Cook County Jail | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Live album by | ||||

| Released | January 1971 | |||

| Recorded | September 10, 1970 | |||

| Venue | Cook County Jail, Chicago, Illinois | |||

| Genre | Blues | |||

| Length | 38:47 | |||

| Label | ABC | |||

| Producer | Bill Szymczyk | |||

| B.B. King chronology | ||||

| ||||

Live in Cook County Jail spent thirty-three weeks on the Billboard Top LPs chart, where it peaked at number twenty-five. It also reached number one on the Top R&B chart, King's only album to do so. In addition to positive reviews from critics, much of the press surrounding Live in Cook County Jail focused on the harsh living conditions in the prison, which led to an eventual reform.

Although Live in Cook County Jail continues to receive praise as one of King's best albums, critics often overlook it in favor of 1965's Live at the Regal. Rolling Stone ranked Live in Cook County Jail at number 499 on its list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time,[1] and in 2002, it was inducted into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame. The performance at Cook County Jail had a profound impact on King, who not only continued to perform free concerts at prisons throughout his life, but also co-established the Foundation for the Advancement of Inmate Rehabilitation and Recreation.

Background

The warden of Cook County Jail, Winston Moore, approached King after a 1970 performance at the popular Chicago nightclub Mister Kelly's and asked him to perform for the prisoners at the jail.[lower-alpha 1] As King recalled: "He said to me, 'It's a first for you at Mister Kelly's and it's a first for me as a black person over here, so why don't we both get together and do another first and get you to play for the inmates?' That's how it came about."[3] King agreed, and politician Jerry Butler (former singer for the Impressions) helped to arrange a special free concert at the jail.[4] Recordings of prison concerts were becoming popular around this time, as indicated by At Folsom Prison by Johnny Cash. Biographer Sebastian Danchin noted this performance was not to cash in on this craze however, but instead was to deliver hope. "The prisoners saw King's visit as an all-too-rare recognition of their humanity" wrote Danchin.[5]

When King told his record label ABC Records that he was going to perform at Cook County Jail, label executives told him to bring along the press and recording equipment.[5] King and his backing band were given a personalized tour of the prison, and were taken through the mess hall and hallway of cells. The musicians felt uncomfortable while walking through the prison; pianist Ron Levy described the stares from the prisoners as "hauntingly hollow".[4] The musicians were given a small stage in the courtyard, while the prisoners were given hundreds of folding chairs.[4]

Live in Cook County Jail was recorded on the afternoon of September 10, 1970.[6] King's backing band consisted of: Levy on the piano, John Browning on the trumpet, Louis Hubert on the tenor saxophone, Brooke Walker on the alto saxophone, Wilbert Freeman on the bass guitar, and Sonny Freeman on the drums.[7] The crowd consisted of 2,117 prisoners,[6] who were required to sit through the performance.[2] Prisoners who wanted to dance were allowed to stand toward the back of the yard.[2] Around 80% of the prisoners attended the performance, while the rest stayed in their cells.[3] King estimated around 70 to 75% of the prisoners were black or of other minority races, and were either in their late teens or early twenties.[5] Prison officials hired additional security for the event, mainly retired boxers.[2]

Composition and recording

Live in Cook County Jail opens with a female official introducing members of the prison administration. A light applause is quickly followed by loud booing.[3] The official then introduces King and his backing band, who begin to play a brief, fast tempo version of "Every Day I Have the Blues".[3] The rest of the setlist in Live in Cook County Jail features slow blues tracks, with lyrical themes of separation and loneliness.[5] King occasionally has conversations with the audience, such as on "Worry, Worry, Worry", where he tells the audience that men and women are God's gift to each other.[6] Biographer David McGee describes these conversations as "a classic bit of bluesman as evangelist or soothsayer".[6]

The setlist in Live in Cook County Jail favors King's early hits – songs which had been in his live repertoire since the 1950s. "3 O'Clock Blues", "Darlin' You Know I Love You", and "Every Day I Have the Blues" were important hits early in his career, while "Please Accept My Love", "Worry, Worry, Worry", and "Sweet Sixteen" date from 1958–1960.[8] The sole contemporary song, 1969's "The Thrill Is Gone", became one of King's biggest hits in recent years.[9] Author Ulrich Adelt believes the setlist was chosen to elicit the feeling of nostalgia from the primarily black audience.[9] To record the performance, producer Bill Szymczyk hired Aaron Baron, the owner of a company called Location Recorders, to record the show from a remote truck. Baron then gave Szymczyk the tapes to be mixed.[6]

Release and reception

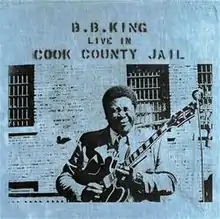

Live in Cook County Jail was released in January 1971, by ABC Records.[10] The album cover features a photo of King playing a guitar lick against the background of blue prison walls and barred windows.[9] It spent thirty-three weeks on the Billboard Top LPs chart, where it peaked at number twenty-five.[11] It also spent thirty-one weeks on the Top R&B chart, and became King's only album to reach number one.[12]

Much of the press surrounding Live in Cook County Jail focused on the jail itself.[2] Journalists interviewed many of the prisoners and learned how some of them had been awaiting their trial for over a year.[13] "A TV network did a big story on that some time later on and they changed the system somewhat and that made me happy. I felt that we had done something good" said King.[3] The press surrounding the jail also gave King greater exposure to a white audience, to the point where a Chicago Tribune reporter felt the need to define blues music for the mainstream readership.[9]

Live in Cook County Jail received positive reviews from critics. Variety wrote: "King's mellow guitar notes and soulful voice shine throughout."[14] Billboard noted the prison setting brought upon new meanings to tracks like "Everyday I Have the Blues" and "Please Accept My Love", before ultimately writing: "King has done it again with this LP".[15] John Landau of Rolling Stone wrote a more mixed review, where he criticized King's tendency to talk too much, as well as the audience's lack of enthusiasm. He did however like Freeman's drumming and King's guitar play, which he described as "in top form from beginning to end".[16]

Legacy

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | A−[18] |

| MusicHound Rock | 4/5[19] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| The Penguin Guide to Blues Recordings | |

Although Live in Cook County Jail continues to receive praise as one of King's best albums, critics often overlook it in favor of Live at the Regal. Ulrich Adelt believes this is because Live at the Regal is routinely cited by critics as one of the greatest blues albums ever made.[22] Neither The Rolling Stone Album Guide or MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide mention Live in Cook County Jail when discussing King's discography, and instead simply assign it a score.[19][20] Reviewing in Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981), Robert Christgau applauded King's "intensity" on renditions of older hits and said, "I prefer the horn arrangements on the Kent originals, but the unpredictable grit with which he snaps off the guitar parts makes up for any lost subtlety."[18]

Rolling Stone listed Live in Cook County Jail at number forty on its list of the greatest live albums ever made,[23] and at number 499 on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.[1] Live in Cook County Jail's entry on the magazine's list of the greatest albums of all time states: "[King] won over the hostile prisoners with definitive versions of his blues standards and his crossover hit 'The Thrill Is Gone.'"[1] In 2002, Live in Cook County Jail was inducted into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame under the category of "Classic of Blues Recording – Album".[24]

The performance at Cook County Jail had a profound impact on King.[3] Saddened by the underlying racist conditions endured by some of the black prisoners, King offered his services for free to not only Cook County Jail but also to other prisons willing to have him.[3] By 1998, King had performed in over fifty prisons. He also established the Foundation for the Advancement of Inmate Rehabilitation and Recreation with attorney F. Lee Bailey in 1972. According to King: "I don't think that when a guy does something wrong he shouldn't be punished, but if he does it as a human being, he should pay for it as a human being."[13]

Track listing

Writing credits adapted from the liner notes of the original 1971 release. Reissues and other recordings often list different writers.[7]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Introductions" | 1:50 | |

| 2. | "Every Day I Have the Blues" | Memphis Slim | 1:43 |

| 3. | "How Blue Can You Get?" | Jane Feather | 5:09 |

| 4. | "Worry, Worry, Worry" | Davis Plumber,[lower-alpha 2] Jules Taub[lower-alpha 3] | 9:57 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Medley: "3 O'Clock Blues", "Darlin' You Know I Love You"" | Jules Taub,[lower-alpha 3] B.B. King[lower-alpha 4] | 6:15 |

| 2. | "Sweet Sixteen" | Ahmet Ertegun | 4:20 |

| 3. | "The Thrill Is Gone" | B.B. King[lower-alpha 5] | 5:31 |

| 4. | "Please Accept My Love" | King,[lower-alpha 6] Sam Ling[lower-alpha 3] | 4:02 |

Personnel

Personnel credits adapted from the liner notes of the original 1971 release.[7]

Musicians |

Production

|

References

Notes

- Clarence Richard English, another warden at Cook County Jail, also claims to have asked King about performing for the prisoners.[2]

- "Davis Plumber" is one of several variations on "Pluma Davis",[25] a trombonist who worked with occasional B.B. King collaborator Bobby "Blue" Bland and other blues and R&B artists.

- "Jules Taub" and "Sam Ling" are among several pseudonyms of record company owners the Bihari brothers, who frequently took co-writing credits for their client's songs.[25]

- Lowell Fulson, who recorded "3 O'Clock Blues" in 1948, is often identified as the song's writer.[25]

- Roy Hawkins and Rick Darnell wrote "The Thrill Is Gone" in 1951.[26]

- "Please Accept My Love" was written by Clarence Garlow.[25]

Footnotes

- "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. May 31, 2012. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- Kapos, Shia (May 15, 2015). "Retired warden remembers day B.B. King played Cook County Jail". Crain's Chicago Business. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- Maycock, James (September 11, 1998). "Pop: And that is why I choose to sing the blues". The Independent. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- Levy, Ron (2013). Tales of a Road Dog: The Lowdown Along the Blues Highway. BookBaby. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-6267-5270-2.

- Danchin, Sebastian (1998). Blues Boy: The Life and Music of B. B. King. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-1-6047-3726-4.

- McGee, David (2005). B.B. King: There is Always One More Time. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-8793-0843-8.

- B.B. King (1971). Live in Cook County Jail (liner notes). ABC Records.

- Whitburn, Joel (1988). "B.B. King". Top R&B Singles 1942–1988. Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin: Record Research. pp. 238–239. ISBN 0-89820-068-7.

- Adelt, Ulrich (2010). Blues Music in the Sixties: A Story in Black and White. Rutgers University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8135-4750-3.

- "The Now Sounds". Billboard. Vol. 83, no. 5. January 30, 1971. p. 34. ISSN 0006-2510.

- "B.B. King Chart History Billboard 200". Billboard. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- "B.B. King Chart History Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums". Billboard. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- McGee, David (2005). B.B. King: There is Always One More Time. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-8793-0843-8.

- "Record Reviews". Variety. Vol. 261, no. 13. February 10, 1971. p. 56. ISSN 0042-2738.

- "The Now Sounds". Billboard. Vol. 83, no. 6. February 6, 1971. p. 34. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Landau, John (March 18, 1971). "Live In Cook County Jail". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- Koda, Cub (n.d.). "B.B. King – Live in Cook County Jail". AllMusic. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- Christgau, Robert (1981). "Consumer Guide '70s: K". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 089919026X. Retrieved February 28, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel (1996). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide (2 ed.). Schirmer Trade Books. p. 631. ISBN 978-0-8256-7256-9.

- Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian David (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide. Simon and Schuster. p. 451. ISBN 978-0-7432-0169-8.

- Russell, Tony; Smith, Chris (2006). The Penguin Guide to Blues Recordings. Penguin. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-140-51384-4.

- Adelt, Ulrich (2010). Blues Music in the Sixties: A Story in Black and White. Rutgers University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8135-4750-3.

- "50 Greatest Live Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. April 29, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- "Award Winners and Nominees" (type B.B. King in the bar labeled "Nominee Name", then search). Blues Foundation. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- Escott, Colin (2002). B.B. King: The Vintage Years (Box set booklet). B.B. King. London: Ace Records. pp. 40, 42, 52. ABOXCD 8.

- Hildebrand, Lee (1990). Superblues: All-Time Blues Hits, Volume One (CD notes). Various artists. Berkeley, California: Stax Records. pp. 1–2. SCD-8551-2.