Ljudski vrt

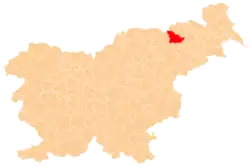

Ljudski vrt (English: People's Garden[3]) is a football stadium in Maribor, Slovenia, which has a seating capacity of 11,709. It has been the home of NK Maribor since their formation in 1960, with the exception of a short period in early 1961. It was originally the home of several other football teams based in Maribor, including Rapid and Branik. A prominent feature of the stadium is the main grandstand with a concrete arch, which is protected by the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia as an architectural and historical landmark.

| Stadion Ljudski vrt | |

Ljudski vrt in 2012 | |

| Location | Maribor, Slovenia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 46°33′44″N 15°38′25″E |

| Owner | City Municipality of Maribor |

| Operator | Šport Maribor |

| Capacity | 11,709 |

| Record attendance | 20,000 (Maribor–Proleter, 8 July 1973) |

| Field size | 105 by 68 metres (115 by 74 yards)[1] |

| Surface | Grass |

| Construction | |

| Built | 1952 |

| Opened | 12 July 1952 |

| Renovated | 1994, 1998, 1999, 2006–2008, 2011, 2020–2021 |

| Expanded | 1960–1962, 1999, 2006–2008 |

| Construction cost | €10 million (2008 reconstruction)[2] |

| Architect | Milan Černigoj and Boris Pipan (old stadium) OFIS Architects (2008 and 2021 reconstruction) |

| Tenants | |

| Branik Maribor (1952–1960) Maribor (1961–present) Slovenia national football team | |

The stadium has four stands: South Stand, East Stand, North Stand, and Marcos Tavares Stand (formerly West Stand). The record attendance of 20,000 was set at a match between Maribor and Proleter in 1973, which was before the ground's conversion to an all-seater stadium in 1998. In addition to being the home of Maribor, the stadium is also occasionally used by the Slovenian men's national football team. Ljudski vrt was also one of the venues of the 2012 UEFA European Under-17 Championship and the 2021 UEFA European Under-21 Championship.

Since its opening in 1952, the stadium has gone through various renovations and reconstructions. In 1994 the stadium received floodlights, and the wooden benches on the grandstand were replaced by plastic seats. In 1999, when Maribor qualified for the UEFA Champions League group stages for the first time, the stadium underwent further renovations and adjustments. However, the biggest renovation took place between 2006 and 2008, when three of the four stands (South, East and North) were demolished and completely rebuilt. The West Stand was renovated between 2020 and 2021.

History

Background

The area, known today as Ljudski vrt, was originally located outside the city walls of Maribor and served as a cemetery for centuries.[4] In 1873, a public park was planted in the area after which the stadium received its present name.[4] At the beginning of the 20th century, the area became a recreational centre of the city, and records from 1901 show that tennis was already being played there at that time.[4][5]

During World War I, the area served as a shooting range.[6] As in other Slovenian towns, football boomed in Maribor after the war with the establishment of new clubs, most notably I. SSK Maribor, which was founded in 1919.[7] The first recorded football activity in the area took place in the late 1900s, when the Marburger Sportvereinigung, a club made up exclusively of high school students, acquired a grass field and converted it into the first real football field.[8] In March 1919, another club, SV Rapid Marburg, was founded.[8] In January 1920, Rapid signed a contract with the Maribor's city authorities to acquire a football field in the area for the next ten years.[8] In the same year, I. SSK Maribor also obtained a football field in the same area.[7] The pitch was completely renovated and the inaugural football match was played on 9 May 1920, when Rapid played against Slovan from Ljubljana and lost 4–2 in front of 1,500 spectators.[8][9] The ground also had a small stand, which was later destroyed during World War II.[10] Other clubs that played in the area of today's Ljudski vrt were Sportklub Merkur, Deutsche Sportklub, SK Hertha, and SK Rote Elf.[8]

Construction and early years

Renovation of the sports infrastructure in Ljudski vrt was the main goal of the new sports organization in most of the late 1940s and early 1950s, and on 12 July 1952, the stadium was opened.[4][11] At the time, the main pitch was fully enclosed by banking, with concrete terraces and seats located on the west side.[11] By 1958, concrete terraces were built along the entire embankment around the pitch, which served as a standing area.[11] Milan Černigoj was the main architect of the stadium. In the late 1950s he was joined by Boris Pipan, with whom he designed a new main grandstand on the west side of the pitch.[11] Construction began in May 1960 and was completed in 1962, with the new club offices, dressing rooms and gyms located beneath it.[11] A prominent feature of the grandstand is the concrete arch, which is protected by the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia (Slovene: Zavod za varstvo kulturne dediščine Slovenije) as an architectural and historical landmark.[12] The primary user of the stadium and the new club offices was to be NK Branik, however, they disbanded in 1960 due to the food poisoning affair, when the club's officials allegedly bribed a hotel waiter to deliberately poison the players of the visiting team, NK Karlovac, before the decisive play-off match for promotion to the Yugoslav Second League.[13] After that, the city of Maribor was left without a professional club, which was one of the reasons why NK Maribor was established on 12 December 1960.[13]

Maribor found its home at Ljudski vrt, and on 25 June 1961, the club played its first match at the stadium, while the main grandstand was still under construction.[14] As most of the stadium had only concrete standing terraces, it was possible to accommodate as many as 20,000 spectators.[15] During the 1967–68 season, when Maribor competed in the Yugoslav First League for the first time, the club renovated the dressing rooms, bathrooms and sanitary facilities, which were in poor condition and inadequate for the top division level.[16]

1990s renovations

Ljudski vrt remained in almost the same state for another thirty years without major developments until the early 1990s.[6] In 1994, the wooden benches on the main grandstand were replaced by plastic seats.[6] The stadium also received renovated dressing rooms and appropriate telecommunication connections.[11] In the same year, on 24 August, the stadium received four floodlight pylons and the first match at night was played between Maribor and Norma Tallinn as part of the 1994–95 UEFA Cup Winners' Cup, won by Maribor 10–0.[6] In 1998, the concrete stands were abolished and replaced by a seating area as part of the ground's conversion to an all-seater stadium.[6] A year later, Maribor became the first and, as of 2023, the only Slovenian club to qualify for the UEFA Champions League.[17] As a result, Ljudski vrt received further renovations, as the VIP area of the main grandstand, dressing rooms and club offices were all renovated.[6] The terraces ring on the east side of the stadium was enlarged by 2,000 seats, bringing the total capacity to 10,030.[11][18] In 2000, an irrigation system was installed,[18] together with a new artificial grass training ground.[11]

2008 reconstruction

Maribor's results in domestic and international competitions in the 1990s were the reason why political and sports officials in the city began to think about a new stadium.[19] In 1997, a tender was held and the "Project Ring" was selected with a plan for a complete renovation and modernisation of the stadium.[20] However, due to financial problems, it took nearly a decade for the project to become a reality, when in 2006 the City Municipality of Maribor and MŠD Branik, with the help of the Government of Slovenia and the European Union, finally raised enough funds to start the first stage of the project.[20]

In the first phase of improvements, worth around €10 million,[2] the existing uncovered stands surrounding the pitch from the north, east and south were demolished and replaced with new covered stands.[4] Construction began in 2006 and was completed in 2008.[4] New stands with a total capacity of 8,500 seats[21] were opened on 10 May 2008 in a league match against Nafta Lendava. The match was played in front of a sold-out crowd of 12,435 spectators, with Maribor winning the game 3–1.[22] The second phase of the project was carried out between 2009 and 2011, and saw the completion of the premises under the East Stand, which includes new dressing rooms, two gyms and a new boiler room.[21][23]

West Stand renovation

.jpg.webp)

In 2014, the stadium barely passed UEFA stadium regulations for international competitions due to the insufficient condition of the West Stand.[4] In August 2015, the first plans to renovate the West Stand were announced.[24] Three years later, in August 2018, NK Maribor and the City Municipality of Maribor presented the entire documentation of the proposed renovation. The new stand was designed by OFIS Architects and was expected to be completed by September 2019.[25] However, the renovation was later postponed to 2020 due to incorrect calculations of project costs, which rose from €5 million to €8 million.[26]

The refurbishment finally started in June 2020[27] and was completed by mid-2021.[28] As part of the renovation, all seats were replaced.[28] Other changes included new underground corridors, elevators, camera platforms, entrances, and landscaping.[28] The arched roof has retained its original appearance.[28] The new capacity of the West Stand is 3,265 seats,[29] and the total capacity of the stadium was reduced to 11,709.[30] There are 651 VIP seats in the stand, of which 120 are in VIP boxes.[31]

In addition to the West Stand, the previously unfinished premises under the North and South stands were completed, which now include a media press centre and dressing rooms and warehouses for the football academy.[32] The total investment costs, including the West Stand and the premises under the North and South stands, amounted to approximately €10 million.[33] The West Stand was renamed as the Marcos Tavares Stand on 14 May 2022, in honour of Marcos Tavares, a longtime captain and the club's all-time most capped player and top goalscorer.[34]

Other uses

International football

Ljudski vrt has hosted a total of 24 international matches of the Slovenia national team.[35] The first was a friendly match against Cyprus on 27 April 1994, which Slovenia won 3–0.[36] The first competitive game was played on 7 September 1994 in the UEFA Euro 1996 qualifiers, when Slovenia hosted Italy.[37] On 18 November 2009, the stadium hosted the 2010 FIFA World Cup play-off match between Slovenia and Russia, which Slovenia won 1–0 in front of 12,510 spectators and thus qualified for the 2010 FIFA World Cup.[38][39] The most recent international to be hosted at Ljudski vrt was Slovenia's 2–1 defeat against Russia on 11 October 2021.[40] The stadium also occasionally hosts the Slovenia under-21 team.[41][42]

.jpg.webp)

In 2012, the stadium was among the four venues that hosted the 2012 UEFA European Under-17 Championship.[43] Ljudski vrt also hosted five matches of the 2021 UEFA European Under-21 Championship, including the semi-final match between Spain and Portugal.[44]

Non sporting events

Aside from sporting uses, the stadium has been occasionally used as a music venue for concerts and other cultural performances.[45] One of the first events at the renovated stadium was the musical Zorba in June 2008, performed by the Slovene National Theatre Maribor, which had an attendance of around 6,000 people.[46] Ljudski vrt was also the venue for the annual Piše se leto concert, organised by the Večer newspaper.[47] In September 2009, Ljudski vrt hosted the main ceremony marking the 150th anniversary of the arrival of Anton Martin Slomšek in Maribor and the tenth anniversary of his beatification. At the ceremony, prelate Santos Abril y Castelló gave a speech in front of about 10,000 spectators.[48] In November 2018, a live televised debate was held at the stadium among 17 candidates for the new mayor of Maribor.[49]

In July 2023, Maribor hosted the 17th European Youth Summer Olympic Festival, with Ljudski vrt hosting the opening ceremony.[50]

Records

The highest attendance recorded at Ljudski vrt is 20,000, for Maribor's match against Proleter in the first leg of the promotion play-offs for the Yugoslav First League, on 8 July 1973.[15][51] The stadium also shares the record with the Stožice Stadium for the highest attendance at a Slovenian League match.[52] This was set in the final round of the 1996–97 season, on 1 June 1997, when there were 14,000 spectators in the match between Maribor and Beltinci, where Maribor secured its first ever league title.[52] In addition, Ljudski vrt is the record holder for the highest average attendance in the Slovenian League season with 5,289, also set in 1996–97.[53]

Transport

Public transport to the stadium includes rail and bus, but there is a lack of dedicated parking spaces.[54] Several bus lines run directly past the stadium. Bus lines 3, 7, 8, 12, 18, 19, and 151 stop less than 150 metres (490 ft) from the stadium, at the bus station located on Gosposvetska street.[55] The stadium is about 15 minutes walk away from the Maribor bus station and the Maribor railway station,[56] which lies on the Pan-European Corridor Xa (connecting Zagreb to Graz)[57] and on the Pan-European Corridor V, which connects Barcelona and Kyiv.[58] The Maribor Edvard Rusjan Airport is about 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) south of the stadium.[59]

References

- "Stadion Ljudski vrt" (in Slovenian). Šport Maribor. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- "Ljudski vrt pričakuje 10 milijonov" (in Slovenian). RTV Slovenija. 3 June 2006. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- Moffat, Colin (20 August 2014). "Maribor v Celtic as it happened". BBC Sport. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- Plestenjak, Rok (7 September 2014). "Stanje je resno: Uefa komaj prižgala zeleno luč za Ljudski vrt" (in Slovenian). Siol. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Historia Docet" (in Slovenian). MŠD Branik. Archived from the original on 18 June 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- "Ljudski vrt: Zgodovina" [Ljudski vrt: History] (in Slovenian). NK Maribor. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- "Prvi slovenski športni klub Maribor 1919–1941" [First Slovene Sports Club Maribor 1919–1941] (in Slovenian). MŠD Branik. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- Mudražija, Tin (2016). "Pionirska vloga Nemcev pri organiziranem igranju nogometa v Mariboru in mariborsko-nemški nogometni klubi". dlib.si (in Slovenian). Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- Meh, Mateja (4 November 2016). "Ljudski vrt, stadion, ki ima za sabo bogato zgodovino". mariborinfo.com (in Slovenian). Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Zgodovina: Predvojni stadioni in igrišča na Slovenskem". Slovenski nogometni portal (in Slovenian). 1 November 2016. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Izgradnja šprotnih objektov po letu 1945" [Construction of sports facilities after 1945] (in Slovenian). MŠD Branik. Archived from the original on 18 June 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- Nejedly, Gorazd (6 January 2019). "Debele krave niso prinesle ničesar". Delo (in Slovenian). Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Zupan, Miha (23 October 2019). "NK Maribor je posledica "afere driska"" (in Slovenian). Nogomania. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Prva tekma NK Maribor v Ljudskem Vrtu" [NK Maribor's first match at Ljudski vrt] (in Slovenian). NK Maribor. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- "Prva finalna kvalifikacijska tekma za vstop v 1. Ligo" (in Slovenian). NK Maribor. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- Vindiš, Tomaž (2008). "Slovenska nogometna kluba iz Maribora in Ljubljane v prvi jugoslovanski ligi med leti 1967–1972" (PDF). fsp.uni-lj.si (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: University of Ljubljana. p. 32. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Viškovič, Rok (14 September 2017). "To so največji podvigi Maribora, včerajšnjega ni med njimi" (in Slovenian). Siol. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Stadion Ljudski Vrt" (in Slovenian). NK Maribor. Archived from the original on 23 November 2001. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- "Investicijski program za izgradnjo Športno-turističnega centra Ljudski vrt – osrednjega prireditvenega stadiona v Mariboru" (in Slovenian). Maribor: City Municipality of Maribor. 16 February 2006.

- "Maribor z rebalansom proračuna do prenovljenega Ljudskega vrta". Dnevnik (in Slovenian). 24 April 2006. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- Križman, Alojz (June 2013). "Prenova stare tribune osrednjega prireditvenega stadiona Ljudski vrt v Mariboru". maribor.si (in Slovenian). Maribor. p. 6. Archived from the original on 25 December 2021. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Premiera pred 12.000 gledalci za čisto desetko" (in Slovenian). RTV Slovenija. 10 May 2008. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Potek investicije ŠTC – Ljudski vrt 2. faza". maribor.si (in Slovenian). Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- Ig. K. (30 August 2015). "Prenova zahodne tribune, lok ostaja". Žurnal24 (in Slovenian). Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- Dajčman, Miha (29 August 2018). "(VIDEO in FOTO) Ljudski vrt bo sprejel manj ljudi, otvoritev septembra 2019". Večer (in Slovenian). Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Krušič Sterguljc, Janez (5 March 2019). "Evropske tekme v Ljudskem vrtu vse do leta 2021 niso ogrožene" (in Slovenian). Maribor: RTV Slovenija. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Rat, Dejan (5 June 2020). "Celovita obnova Glavnega trga končana v drugi polovici junija" (in Slovenian). RTV Slovenija. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- "Obnovljeni Ljudski vrt s kipom Josipa Primožiča - Toša" (in Slovenian). Siol. 15 October 2021. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Ljudski vrt s prenovljenim zahodom dokončno prenovljen v celoti". To. G. (in Slovenian). RTV Slovenija. 15 October 2021. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Osebna izkaznica" (in Slovenian). NK Maribor. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- Lorenčič, Jaša (30 August 2021). "DNEVNA: VIP sedeži: lepi, novi in prazni". maribor24.si (in Slovenian). Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- Ropert, Florijan (11 March 2020). "Dela v Ljudskem vrtu še stojijo, ponudbe izvajalcev previsoke". Slovenski nogometni portal (in Slovenian). Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- R. P. (21 May 2020). "Mariborčani so si oddahnili: Velik dan za mesto in nogomet!" (in Slovenian). Siol. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- A. G. (14 May 2022). "Vijoličasti strli Aluminij; Tavares: Nikoli si nisem mislil, da bom postal legenda" (in Slovenian). RTV Slovenija. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- "Stadion Ljudski Vrt, Maribor". eu-football.info. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Slovenia vs Cyprus, 27 April 1994". eu-football.info. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Slovenia vs Italy, 7 September 1994, Euro 1996 Qualifying". eu-football.info. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Slovenia vs Russia, 18 November 2009, World Cup qualification". eu-football.info. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Slovenija drugič v zgodovini na svetovnem prvenstvu" [Slovenia at the World Cup for the second time]. sta.si (in Slovenian). Slovenian Press Agency. 18 November 2009. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Slovenia vs Russia, 11 October 2021, World Cup qualification". eu-football.info. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Stadion Ljudski vrt". nzs.si (in Slovenian). Football Association of Slovenia. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- R. Š. (17 November 2020). "U21: Slovenci remizirali tudi proti Rusom". Slovenski nogometni portal (in Slovenian). Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- "U17 EURO 2012 Eslovenia – Stadiums". worldfootball.net. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Ljudski vrt, Maribor (Slovenia) – Fixtures & Results". worldfootball.net. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- Cehnar, Jasmina (21 March 2017). "Ljudski vrt: Brez pravih rešitev za najbolj ugledno tribuno, ki to več ni". Večer (in Slovenian). Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Uradna otvoritev stadiona Ljudski vrt z Grkom Zorbo". maribor.si (in Slovenian). Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- "Piše se leto v Mariboru" (in Slovenian). Siol. 23 June 2008. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- S. Z. (26 September 2009). ""Slomšek – duhovni oče slovenskega naroda"" (in Slovenian). Maribor: RTV Slovenija. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- La. Da.; G. K. (8 November 2018). "Kandidati za mariborski županski stolček o kulturi, prometu in povezovanju bregov" (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: RTV Slovenija. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Rupar, Timotej (23 July 2023). "V Mariboru slavnostno odprtje festivala evropske mladine (FOTO)". Sportklub (in Slovenian). Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- Brdnik, Žiga (10 March 2015). "Nogometni stadioni: Milijoni za prazne tribune". Dnevnik (in Slovenian). Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Stožice ujele Ljudski vrt". Slovenski nogometni portal (in Slovenian). 8 May 2016. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Maribor drugič v zgodovini SNL preko štiri tisoč". Slovenski nogometni portal (in Slovenian). 1 June 2015. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- Mejal, Aljaž (7 October 2020). "Garažna hiša ob Ljudskem vrtu v letu 2025" (in Slovenian). RTV Slovenija. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Marprom WEBMap | Mestni avtobusni potniški promet v MOM". marprom.si (in Slovenian). Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "NK Maribor to Avtobusna postaja Maribor". Google Maps. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- Susaj, Elizabeta; Kucaj, Enkelejda (2018). "Development Of Pan-European Road Corridor X In Last Two Decades". academia.edu. Polis University. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Infrastructure and utilities". Invest Podravje Slovenia. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Mladinska ulica 29 to Aerodrom Maribor P.O." Google Maps. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

External links

- Ljudski vrt at Šport Maribor (in Slovene)

- Ljudski vrt at NK Maribor (in Slovene)

.jpg.webp)