Long Walls

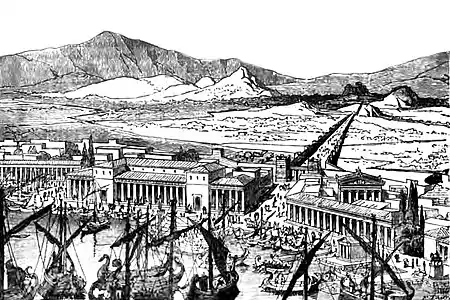

Although long walls were built at several locations in ancient Greece, notably Corinth and Megara,[1] the term Long Walls (Ancient Greek: Μακρὰ Τείχη [makra tei̯kʰɛː]) generally refers to the walls that connected Athens' main city to its ports at Piraeus and Phaleron. Built in several phases, they provided a secure connection to the sea even during times of siege. The walls were about 6 km (3.7 mi) long .[2] Construction began in the mid-5th century BC, and the walls were destroyed by the Spartans in 403 BC after Athens' defeat in the Peloponnesian War. They were rebuilt with Persian support during the Corinthian War in 395–391 BC. The Long Walls were a key element of Athenian military strategy, since they provided the city with a constant link to the sea and thwarted sieges conducted by land alone.

History

Background

The ancient wall around the Acropolis was destroyed by the Persians during the occupations of Attica in 480 and 479 BC, part of the Greco-Persian Wars. After the Battle of Plataea, the invading Persian forces were removed and the Athenians were free to reoccupy their land and begin rebuilding their city. Early in the process of rebuilding, construction started on new walls around the city proper.

This project drew opposition from the Spartans and their Peloponnesian allies, who were alarmed by the recent increase in the power of Athens. Spartan envoys urged the Athenians not to go through with the construction, arguing that a walled Athens would be a useful base for an invading army, and that the defenses of the Isthmus of Corinth would provide a sufficient shield against invaders.

However, despite these concerns, the envoys did not strongly protest and in fact gave helpful advice to the builders. The Athenians disregarded their negative arguments, fully aware that leaving their city unwalled would place them utterly at the mercy of the Peloponnesians;[3] Thucydides, in his account of these events, describes a series of complex machinations by Themistocles through which he distracted and delayed the Spartans until the walls were built up high enough to provide adequate protection.[4]

Beginnings

In the early 450s BC, fighting began between Athens and various Peloponnesian allies of Sparta, particularly Corinth and Aegina. In the midst of this fighting between 462 BC and 458 BC, Athens had begun construction of two more walls, the Long Walls, one running from the city to the old port at Phalerum, the other to the newer port at Piraeus. In 457 BC, a Spartan army defeated an Athenian army at Tanagra while attempting to prevent the construction, but work on the walls continued and they were completed soon after the battle.[3] These walls ensured that Athens would never be cut off from supplies as long as she controlled the sea. These Phase 1a walls [5] enclosed a vast area and included Athens' two main ports.

Athenian strategy and politics

The building of the Long Walls reflected a larger strategy that Athens had come to follow in the early 5th century. Unlike most Greek city states, which specialized in fielding Hoplite armies, Athens had focused on the navy as the centre of its military since the time of the building of her first fleet during a war with Aegina in the 480s BC.

With the founding of the Delian League in 477 BC, Athens became committed to the long-term prosecution of a naval war against the Persians. Over the following decades, the Athenian navy became the mainstay of an increasingly imperial league, and Athenian control of the sea allowed the city to be supplied with grain from the Hellespont and Black Sea regions. The naval policy was not seriously questioned by either democrats or oligarchs during the years between 480 and 462 BC, but later, after Thucydides son of Melesias had made opposition to an imperialist policy a rallying cry of the oligarchic faction, the writer known as the Old Oligarch would identify the navy and democracy as inextricably linked, an inference echoed by modern scholars.[6] The long walls were a critical factor in allowing the Athenian fleet to become the city's paramount strength.

With the building of the Long Walls, Athens essentially became an island within the mainland, in that no strictly land-based force could hope to capture it.[7] (In ancient Greek warfare, it was all but impossible to take a walled city by any means other than starvation and surrender.) Thus, Athens could rely on her powerful fleet to keep her safe in any conflict with other cities on the Greek mainland.

The walls were completed in the aftermath of the Athenian defeat at Tanagra, in which a Spartan army defeated the Athenians in the field but was unable to take the city because of the presence of the city walls; seeking to secure their city even against siege, the Athenians completed the long walls; and, hoping to prevent all invasions of Attica, they also seized Boeotia, which, as they already controlled Megara, put all approaches to Attica in friendly hands.[8] For most of the First Peloponnesian War, Athens was indeed unassailable by land, but the loss of Megara and Boeotia at the end of that war forced the Athenians to turn back to the long walls as their source of defense.

The Middle Wall

During the 440s, the Athenians supplemented the existing two Long Walls with a third structure (Phase 1b).[9] This "Middle Wall" or "Southern Wall" was built to mirror the original Athens–Piraeus Wall and was constructed to be another wall connecting the city to Piraeus.

There are many known possibilities for the purpose of the Middle Wall, such as: it was thought to have been built as a back-up defense in case someone penetrated the first Athens-Piraeus Wall. This was proven false however due to the construction of the wall. Its main access points were built so that it would withstand attacks only from the direction of Phaleron. After the naval challenges of 446 BC, Athens was no longer the complete dominant power of the sea, so the Middle Wall is more a backup structure for the Athens–Phaleron Wall. The distance between the two original (phase Ia) walls left a substantial amount of room for amphibious invasions along the coast, and with this new wall, Athenians could retreat within the more narrow area of the two Athens-Piraeus Walls.

Also by the time the Middle Wall was built, in the mid-fifth century, the importance of the Athenian ports had changed. Piraeus had become the principal economic and military harbor, while Phaleron had begun to lapse into obscurity. This development will have caused a re-evaluation of the fortification system which secured Athens' connection with its ships.[10]

The Peloponnesian War

In Athens' great conflict with Sparta, the Peloponnesian War of 432 BC to 404 BC, the walls came to be of paramount importance. Pericles, the leader of Athens from the start of the war until his death in 429 BC in the plague that swept Athens, based his strategy for the conflict around them. Knowing that the Spartans would attempt to draw the Athenians into a land battle by ravaging their crops, as they had in the 440s, he commanded the Athenians to remain behind the walls and rely on their navy to win the war for them.

As a result, the campaigns of the first few years of the war followed a consistent pattern: The Spartans would send a land army to ravage Attica, hoping to draw the Athenians out; the Athenians would remain behind their walls, and send a fleet to sack cities and burn crops while sailing around the Peloponnese. The Athenians were successful in avoiding a land defeat, but suffered heavy losses of crops to the Peloponnesian raids, and their treasury was weakened by the expenditures on the naval expeditions and on import of grain. Furthermore, a plague ravaged the city in 430 BC and 429 BC, with its effects being worsened by the fact that the entire population of the city was concentrated inside the walls.

The Athenians continued to use the walls for protection through the first phase of the war until the seizure of Spartan hostages in 425 BC, during the Athenian victory at Pylos. After that battle, the Spartans were forced to cease their yearly invasions until 413 BC, since the Athenians threatened to kill the hostages if an invasion was launched.

In the second phase of the war, the walls again became central to the strategy of both sides. The Spartans occupied a fort at Decelea in Attica in 413 BC, and placed a force there that posed a year-round threat to Athens. In the face of this army, the Athenians could only supply the city by sea. Athens was also weakened from the disastrous conclusion of the Sicilian Expedition and began to modify their walls in the summer of 413 BC and ultimately abandoned the Athens-Phaleron Wall, focusing on the two Piraeus Walls.

The Long Walls, and the access to a port that they provided, were by now the only thing protecting Athens from defeat. Realizing that they could not defeat the Athenians on land alone, the Spartans turned their attention to constructing a navy, and throughout the final phase of the war devoted themselves to trying to defeat the Athenians at sea. Their eventual success, Aegospotami, cut the Athenians off from their supply routes and forced them to surrender. One of the most important terms of this surrender was the destruction of the long walls which were dismantled in 404 BC. The peace treaty that was reached in the same year also provided the termination of Athens' naval power. Xenophon tells us that the long walls were torn down with much jubilation and to the song of flute girls.

Rebuilding of the Long Walls

Following their defeat in 404, the Athenians quickly regained some of their power and autonomy, and by 403 BC had overthrown the government that the Spartans had imposed on them. By 395 BC, the Athenians were strong enough to enter into the Corinthian War as co-belligerents with Argos, Corinth, and Thebes against Sparta.

For the Athenians, the most significant event of this war was the rebuilding of the Long Walls. By 395 BC the rebuilding of the fortifications had begun and according to the Athenian admiral Conon, the walls had reached their final stages by 391 BC. In 394 BC, a Persian fleet under satrap Pharnabazus II and Conon decisively defeated the Spartan fleet at the Battle of Cnidus, and, following this victory, Pharnabazus sent Conon with his fleet to Athens, where it provided aid and protection as the Long Walls were rebuilt.

Thus, by the end of the war, the Athenians had regained the immunity from land assault that the Spartans had taken from them at the end of the Peloponnesian War. The rebuilt walls stood for many years, unchallenged, and were never mentioned to have been incorporated in Athens' defense planning until after the 340s BC.

According to Xenophon in Hellenica:

Conon said that if he (Pharnabazus) would allow him to have the fleet, he would maintain it by contributions from the islands and would meanwhile put in at Athens and aid the Athenians in rebuilding their long walls and the wall around Piraeus, adding that he knew nothing could be a heavier blow to the Lacedaemonians than this. (...) Pharnabazus, upon hearing this, eagerly dispatched him to Athens and gave him additional money for the rebuilding of the walls. Upon his arrival Conon erected a large part of the wall, giving his own crews for the work, paying the wages of carpenters and masons, and meeting whatever other expense was necessary. There were some parts of the wall, however, which the Athenians themselves, as well as volunteers from Boeotia and from other states, aided in building.

The Long Walls in the 4th century BC

From the Corinthian War down to the final defeat of the city by Philip of Macedon, the Long Walls continued to play a central role in Athenian strategy. The Decree of Aristoteles in 377 BC reestablished an Athenian league containing many former members of the Delian League. By the middle of the 4th century, Athens was again the preeminent naval power of the Greek world, and had reestablished the supply routes that allowed it to withstand a land-based siege.

The Long Walls had become obsolete and the length and location of the structures rendered them dangerously vulnerable to the advanced siege techniques of the day. The Athenians began to strengthen their urban defense systems by rebuilding the Long Walls again to be able to withstand contemporary methods of assault in 337 BC. The new walls included attributes such as substructures built of cut blocks and possibly even roofs above the walk-ways.

However, the Athenians were not in a position to use the new Long Walls until Alexander the Great's death in 323 BC. By this time Athens' navy had been crushed in the Lamian War and they became subordinate to the Macedonians and the use of the Long Walls in a naval strategy was ruled out. Macedonian leaders controlled cities on both sides of the Long Walls and they had little use for these fortifications, thus the mid-fourth century Long Walls were never actually employed.[13]

Later history

The walls were still standing at the beginning of the 1st century BC. However, during the First Mithridatic War, the Siege of Athens and Piraeus (87–86 BC) was won by the Roman general Sulla and he destroyed the Long Walls.

See also

Sources

- G.E.M. de Ste. Croix. The Origins of the Peloponnesian War. Duckworth and Co., 1972. ISBN 0-7156-0640-9

- Fine, John V. A. The Ancient Greeks: A Critical History. Harvard University Press, 1983. ISBN 0-674-03314-0

- Hornblower, Simon and Spawforth, Anthony ed. The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-19-866172-X

- Kagan, Donald. The Peloponnesian War. Penguin Books, 2003. ISBN 0-670-03211-5

- Kagan, Donald. The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War. Cornell, 1969. ISBN 0-8014-9556-3

- Conwell, David H. Connecting a City to the Sea: The History of the Athenian Long Walls. Brill NV, 2008. ISBN 978-90-04-16232-7

References

- "Long Walls, the," from The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth, ed.

- Mark Cartwright (June 2, 2013). "Piraeus". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 330

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War 1.90–91

- Conwell, David H. Connecting a City to the Sea: The History of the Athenian Long Walls. Brill NV, 2008. ISBN 978-90-04-16232-7

- Kagan, in The Peloponnesian War, describes the oligarchy of 411 BC as fundamentally untenable so long as the fleet remained the crucial military arm of Athens.

- Kagan, Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 87

- Kagan, Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 95

- Conwell, Connecting a City to the Sea, 77

- Conwell, Connecting a City to the Sea, 76

- Smith, William (1877). A History of Greece from the Earliest Times to the Roman Conquest. William Ware & Company. p. 419.

- Xenophon. Perseus Under Philologic: Xen. 4.8.7. Archived from the original on 2020-08-03. Retrieved 2019-05-01.

- Conwell, Connecting a City to the Sea, 158