Longju

Longju or Longzu[1] (Tibetan: གླང་བཅུ, Wylie: glang-bcu; Chinese: 朗久; pinyin: Lǎngjiǔ) is a disputed area[lower-alpha 2] in the eastern sector of the China–India border, controlled by China but claimed by India. The village of Longju is located in the Tsari Chu valley 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) south of the town of Migyitun, considered the historical border of Tibet.[5] The area of Longju southwards is populated by the Tagin tribe of Arunachal Pradesh.

India had set up a border post manned by Assam Rifles at Longju in 1959, when it was attacked by Chinese border troops and forced to withdraw. After discussion the two sides agreed to leave the post unoccupied.[6] India established a new post at Maja,[lower-alpha 3] three miles to the south of Longju,[9] but continued to patrol up to Longju.[10] After the 1962 Sino-Indian War, the Chinese reoccupied Longju and brushed off Indian protests.[10]

Since late 1990s and early 2000s, China has expanded further south, establishing a battalion post at erstwhile Maja.[11][12] In 2020, China built a 100-house civilian village close to this location in disputed territory.[10][12]

Location

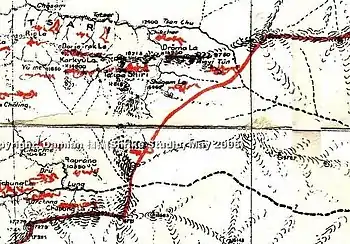

Longju is 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi)[lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 5] south of the Tibetan frontier town of Migyitun (Tsari Town), along the Tsari Chu river valley. The area was historically populated by the Mara clan of the Tagin tribe of Arunachal Pradesh.[10] The border between Tibet and tribal territory was at the Mandala Plain just outside the town of Migyitun.[5]

There was a crossing on the river from its left bank to the right bank near Longju,[18] which was needed to enter the tribal territory from the Tibetan side. When Bailey and Morshead visited the area in 1905, they found the bridge broken. The Tibetans were unable to repair it because it was built using the tribal materials and techniques. Evidently the Tibetan authority stopped at Migyitun.[19][14]

On 28 August 1959 the Indian Prime Minister Nehru explained to the parliament that Longju was a five days march from Limeking which in turn was a 12 days march from the nearest road at Daporijo, a total of about three weeks.[20] At the time the route passed through dense forests and consisted of indigenously built "ladder climbs" and bridges.[2]

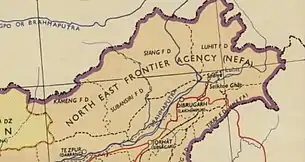

Administratively, for China, Longju is located in Shannan, Tibet, while for India, it is located in Upper Subansiri district (previously called the Subansiri Frontier Division).[21]

History

McMahon Line

During the negotiations for the McMahon Line in 1914, the British Indian negotiators were cognizant of the fact that Migyitun was Tibetan and also that the neighbouring Dakpa Sheri mountain (to the west) was regarded by them as a holy mountain. Taking these factors into account, they promised that the border would be drawn short of the high ridge line, and avoid including the annual pilgrimage route in Indian territory as far as practicable.[22]

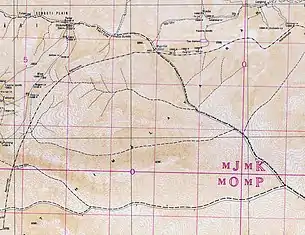

These arrangements were confirmed in the notes exchanged between McMahon and Lonchen Shatra and the border line was drawn accordingly. The line avoided both the north–south ridge line (which would have placed Dakpa Sheri on the border) and the east–west ridge line (which would have placed Migyitun on the border), and cut across the region along a rough diagonal. A suitable buffer south of Migyitun was included within Tibet, but not so much as to include the confluence of the Mipa Chu river with Tsari Chu. McMahon believed that there was a "wide continuous tract of uninhabited country" along the south of the watershed.[23]

As per the US Office of Geographer's "Large-Scale International Boundaries" (LSIB) database, the McMahon Line of the treaty puts Longju in Tibetan territory.[24]

1930s

For various diplomatic reasons, the McMahon Line remained unimplemented for a couple of decades. It was revived in 1930s by Olaf Caroe, then Deputy Foreign Secretary of British India. The notes exchanged between McMahon and Lonchen Shatra were published in a revised volume of Aitchison's Treaties and maps were revised to show the McMahon Line as the boundary of Assam. The Surveyor General of India made adjustments to the McMahon Line boundary "based on more accurate topographical knowledge acquired after 1914". But he left certain portions approximate as he did not have enough information. Scholar Steven Hoffmann remarks that Migyitun, Longju and Thagla Ridge (in Tawang) were among such places.[25]

The maps drawn from 1937 onwards show the boundary tend more towards the watershed near Migyitun than the original treaty map. The Dakpa Sheri mountain and the annual pilgrimage route are still shown entirely within Tibetan territory. But, at Migyitun, the border is immediately to its south, evidently putting Longju within Indian territory.[lower-alpha 6] This is the correct ethnic frontier, according to scholar Toni Huber.[5]

1950s

After India became independent 1947, it slowly extended its administration to all the remaining areas of the North-East Frontier. The Subansiri area was renamed Subansiri Frontier Division and officers were posted to remote areas. Schools and medical centres were opened. Verrier Elwin, an authority on Indian tribal communities, stated "wars, kidnappings and cruel punishments... have come to an end".[26]

In 1950, Tibet came under Chinese control but, at least initially, this made little difference to the relations between the Tibetans and Tagin tribes. In 1956, the Tibetans conducted the long pilgrimage of the Dakpa Sheri mountain called Ringkor as per their 12-year cycle. The procession went through the tribal territory (along the Tsari Chu river until its confluence with Subansiri and then upstream along Subansiri or "Chayul Chu"). It passed without any incidents from the tribals. The Tibetans paid them the usual 'tribute' to let the procession pass unmolested, but also armed Indian border troops were stationed in the Tsari Chu valley south of the Mandala Plain.[27][10]

Scholar Toni Huber reports that there was a 'foreign presence' in Tsari in terms of several small Chinese medical teams sent by Chinese administrators in Lhasa. The medical teams set up camp in the Mandala Plain and other locations on the Tibetan side of the border. They treated any assembled pilgrims that were sick and dispensed medicines. After the procession departed, they left. Tibetans later suspected that these apparently innocent medical teams represented reconnaissance teams sent in advance of the later Chinese encroachments in the border area in 1959.[28]

By the beginning of 1958, China had completed the Aksai Chin Road and obtained the capacity for large-scale troop movement into Tibet.[29] In March 1959, an uprising erupted in Tibet, and troops moved in to quell it. The PLA was deployed along the McMahon Line,[30] and four regiments were deployed in the Shannan region bordering Subansiri and Kameng Divisions.[21][31] In response, India set up advance posts manned by Assam Rifles[lower-alpha 7] along the border. The two places where the map-drawn McMahon Line differed from the prevailing ethnic frontier, the Khinzemane post along the Nyamjang Chu valley and Longju in the Tsari Chu valley, came in for contestation. The Chinese suppression of the Tibetan uprising and India's decision to grant asylum to the Dalai Lama inflamed the public opinion on both sides.[33]

Longju incident

On 23 June 1959, China handed a protest note to the Indian embassy in Beijing, alleging that hundreds of Indian troops had intruded into and occupied Migyitun (among other places). Migyitun was said to have been "shelled" and the Indian troops were alleged to be working in collusion with "Tibetan rebel bandits". The Indian government denied that any such actions took place.[34] There is no record of any Tibetan armed resistance operating in the Migyitun area.[28] Evidently, the Chinese were highlighting the discrepancy between the map-marked McMahon Line and the Indian-claimed border.

On 7 August, Chinese forces initiated hostilities at Khinzemane as well as Longju, pushing back the Indian post at the former and "actual fighting" at the latter.[35][33] Reports state that a Chinese force of two to three hundred men was used to drive out the Indian border troops from Longju.[36] On 25 August, they surrounded a forward picket consisting of 12 personnel (one NCO and 11 riflemen),[37] and fired upon it killing one and wounding another. The rest were taken prisoner although some escaped.[38] The following day, the Longju post itself was attacked with an overwhelming force. After some fighting, the entire Longju contingent withdrew to Daporijo.[39] Chinese troops began to entrench themselves at the Indian Longju post, digging mines and building airfields, demarcating it as their territory.[40]

When the Indian government protested about the incident, the Chinese replied that it was the Indian troops that opened fire and later "withdrew ... on their own accord".[41][37] They also said that Longju was in Tibetan territory according to the McMahon Line.[33]

Aftermath

The Indian media reported the 25 August attack on Longju on 28 August 1959. Nehru faced questions in the parliament on the same day. He revealed that serious border incidents occurred between India and China along the Tibet border. Nehru went on to reference four cases: Aksai Chin Road, Pangong Lake area, Khinzemane and Longju.[42] He also announced that the border would be the responsibility of the military from then onwards.[43][44]

The Longju incident came while numerous questions were already being raised in India based on leaks and news reports. In order to stem the "tide of criticism", Nehru had decided to publish the entire correspondence with the Chinese government as a "white paper". The first of these appeared on 7 September. In due course the white papers would severely restrict Nehru's room for diplomatic manoeuvre.[45]

On 8 September, Nehru received a reply from the Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai to his letter from March 1959 quizzing about the Chinese maps claiming Indian territory. Zhou stated that the maps were "substantially correct", thereby laying claim to the entire state of Arunachal Pradesh as well as Aksai Chin.[46] (Until this point Zhou had been claiming that PRC was just reprinting the old Kuomintang maps and hadn't had the time to examine the boundary question.)[47]

In the same letter, Zhou also proposed that border differences should be settled through negotiations and that the "status quo" should be maintained until such settlement.[48][49][lower-alpha 8] Nehru accepted the proposal in his response. He indicated that the Indian forces would withdraw from Tamaden—another location where the McMahon Line was contested—and invited Zhou to do the same at Longju, while reassuring him that the Indian forces would not reoccupy it.[53] The Chinese forces are said to have subsequently withdrawn from the Indian post at Longju, but remained in force at Migyitun.[lower-alpha 9]

On 2 October 1959, a discussion took place between Soviet and Chinese delegations in which Khrushchev asked Mao "Why did you have to kill people on the border with India?" to which Mao replied that India attacked first. Zhou Enlai, also present at the discussion then asked Khrushchev "What data do you trust more, Indian or ours?" Khrushchev replied that there were no deaths among the Chinese and only among the Hindus.[54]

Commentaries

Scholar Stephen Hoffmann states that while the Indians were trying to strengthening the NEFA frontier, the Chinese were engaged in "militarizing" it. Since the Indian-claimed border was undemarcated and the Chinese troops were convinced of links between the Indians and the hostile Tibetans, incidents were bound to occur.[33]

Vertzberger notes that the Longju incident took place in the larger context of deteriorating relations between China and India. China was suspicious of India's support of Tibetan activities while India was witnessing an aggressive China which was completely disregarding the 1951 agreement. The incident marked the transition in China–India relations from "verbal to physical violence".[55]

1960s

On 29 August 1959 Assam Rifles set up a new post at the village of Maja, which was 3 miles (4.8 km) south of Longju.[9][lower-alpha 10] In November 1959, Nehru proposed to Zhou that both the sides withdraw from Longju and Zhou accepted.[57][58] However, it is doubtful if the Chinese forces withdrew, since they later called it a "pure fabrication" there was such an agreement.[59][60]

In January 1962, the village of Roi,[lower-alpha 11] half a mile south of Longju, was occupied by the Chinese. When India protested the action, the Chinese replied that Roi was in their territory.[58][61]

The Longju sector did not witness any fighting during the 1962 war. After noticing that the Chinese attacks were being launched with overwhelming forces, all the border posts in the area were withdrawn. Indian posts were manned by paramilitary Assam Rifles, and it was not feasible to reinforce them with regular military due to lack of infrastructure.[63] The Maja post was abandoned on 23 October 1962. The Indian history of the war states that the withdrawing troops faced an attack from the rear 8 km south of Maja.[64] Subsequently, the Chinese troops occupied the entire area up to Limeking until 21 November 1962. After the ceasefire, they withdrew to their previous positions.[65][66]

After the 1962 war, India and China continued to blame each other in correspondence over Longju and other sensitive areas. On 25 June 1963, in a reply note to India, China said that its "frontier guards have long since completely withdrawn from the twenty-kilometre zones on the Chinese side of the line of actual control of November 7, 1959. As for Longju, it has always been part of China's territory [...] However, in order to create an atmosphere conducive to direct negotiations between the two sides, China has vacated it as one of the four disputed areas and has not even established any civilian checkpost there."[67]

In the midst of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, India reported that 400 Chinese troops entered into Longju area and intruded to a depth of 2 miles into the Subansiri district.[68] This was part of a larger series of incursions spanning the western, middle and eastern sectors.[69]

Current developments

During 2019–2020, China has constructed a new village near Longju, further into Indian claimed territory.[70] The village is marked on Chinese maps as "Lowa Xincun" ("Lowa New Village"; Chinese: 珞瓦新村; pinyin: Luò wǎ xīncūn), and located at the confluence of the Mipa Chu river with Tsari Chu, a few yards north of the traditional Maja village. (Map 5.) NDTV News quoted a military analyst saying that China has maintaind a small forward position in the valley since 2000, which has been apparently uncontested by India. This has allowed China to gradually upgrade mobility in the valley eventually leading to the construction of the new village.[70][71]

Notes

- The border is the Line of Actual Control between China and India as marked by the contributors to the OpenStreetMap.

- The area is sometimes informally referred to as the Longju sector.[2][3][4]

- Alternative spellings include Majha[7] and Maza.[8]

- Distance as per modern maps.[13] In 1905, Bailey had estimated the distance to be 4 miles,[14][15] which is an overestimate that would take us to the mouth of the Mipa Chu river. A Chinese clarification question in the 1961 "Report of the Officials" related to the distance between Longju and Migyitun was answered by India as "the distance between Longju and the alignment south of Migyitun was about two miles."[16]

- The Survey of India's coordinates for Longju are 28.6425973°N 93.3814961°E.[17]

- The crossing on the Tsari Chu river, which is said to have been near Longju, is well south of the boundary in the Survey of India map.

- Prime Minister Nehru characterised the Assam Rifles as "civil constabulary, equipped with light arms".[32]

- In his response, Nehru pointed out a long list of actions of China that violated the "status quo".[50] Throughout the border conflict of the 1960s, China always claimed that the Chinese gains were part of the "status quo", while branding Indian efforts to block them as "invasions".[51][52]

- Hoffmann (1990, p. 72) states that the Chinese withdrew in October, but also that the Indians doubted that this had actually happened (footnote 41). See also Sandhu, Shankar & Dwivedi (2015, p. 108). In December 1962, the Chinese said it was a "pure fabrication" that they had agreed to withdraw (Johri (1965, p. 253)).

- The Indian official history of the war says that Maja was 6 miles (9.7 km) south of Longju.[56] According to B. M. Kaul, this was the walking distance, with 3 miles being the aerial distance.

- Also referred to as Longju Roi. Alternative spellings include Roy, Ryu[61] and Ruyu.[62]

Citations

- Kalita, Prabin (19 September 2020). "Defence forces on toes in six areas along LAC in Arunachal Pradesh". The Times of India. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- Sali, M. L. (1998). India-China Border Dispute: A Case Study of the Eastern Sector. APH Publishing. p. 144. ISBN 978-81-7024-964-1.

- Mayilvaganan, M.; Khatoon, Nasima; Bej, Sourina (11 June 2020). Tawang, Monpas and Tibetan Buddhism in Transition: Life and Society along the India-China Borderland. Springer Nature. p. 42. ISBN 978-981-15-4346-3.

- Mullik 1971, p. 414.

- Huber 1999, p. 170: "It was there on August 26, 1959, that the very first violent conflict in the Sino-Indian dispute over the McMahon line erupted, as a Chinese force of two to three hundred crossed the traditional border at mandala Plain and drove out Indian frontier troops stationed at the advance post of Longju in the lower Tsari valley."

- Hoffmann 1990, p. 72.

- China hatching new conspiracy near Arunachal Pradesh border after defeat in Ladakh, Zee News, 20 September 2020.

- How much land did Arunachal Pradesh lose to China after 1962 war?, EastMojo, 24 June 2020.

-

- Johri 1965, pp. 253–254: "The Government of India took steps to establish a new post in the south of Longju. A platoon of the Assam Rifles under Captain Mitra established a post at Maja, three miles in the south of Longju."

- Kaul 1967, p. 232: "This gallant officer [Captain Mitra], however, established our post at Maja instead, about six miles South of Long-ju (and about three miles or less as the crow flies)."

- Arpi, Claude (21 January 2021). "Chinese village in Arunachal: India must speak up!". Rediff.

- Bhat, Col Vinayak (22 June 2018). "Despite Modi-Xi bonhomie, China moves into Arunachal Pradesh, builds new road and barracks". The Print.

- Prabin Kalita, Pentagon-cited China village a PLA camp: Arunachal official, The Economic Times, 7 November 2021. "The mountainous area where structures built by the PLA now stands used to be the last post of the Indian Army until the 1962 War. Back then, the post was called Maza Camp."

- Route from Zhari township to Longju, OpenStreetMap, retrieved 8 November 2022.

- Bailey, F. M. (1957), No Passport to Tibet, London: Hart-Davis, p. 203 – via archive.org: "Morshead went further down the river to see what prospect there was of exploring the No Man's Land. But four miles down he came on the ruins of a foot-bridge over to the right bank and could get no further. It was one of the Mishmi type, five long strands of cane bound at intervals with hoops. The Tibetans had tried to build another, but they lacked the skill of the Lopas."

- Rose & Fisher 1967, p. 9.

- "Report of the Officials of the Governments of India and the People's Republic of China on the Boundary Question - Part 1" (PDF). Ministry of External Affairs, India, 1961. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- Named places 2022, Survey of India dataset, retrieved 8 November 2022.

- Rose & Fisher 1967, p. 10.

- Rose & Fisher 1967, p. 9: "Bailey has left no doubt that Tibetan authority stopped at the frontier town of Migyitun. He wished to cross to the Indian side but was unable to do so. The cane bridge across the Tsari had been destroyed, and when he asked the Tibetans to rebuild it, they insisted that they lacked the skill for a bridge of that type"

- Bhargava, G S (1964). The Battle of NEFA: The Undeclared War. New Delhi: Allied Publishers. pp. 49–50.

- Sandhu, Shankar & Dwivedi 2015, p. 108.

- Mehra 1974, pp. 228–229: "He [Charles Bell], therefore, planned to inform the Lonchen that the proposed boundary line left the highest mountain ranges before reaching the Tsari heights thereby placing the latter, and the short pilgrimage route, in Tibetan territory. But a part of it did perhaps come within British domain.... Bell, on his part, undertook to ensure that the frontier would be so laid as to leave Migyitun on the Tibetan side. Such monasteries and other sacred places as fell into British territory, he had already assured the Lonchen, would be protected and put to no harm."

- Mehra 1974, pp. 231–232.

- Large Scale International Boundaries (LSIB), Europe and Asia, 2012, EarthWorks, Stanford University, 2012.

- Hoffmann 1990, pp. 21–22.

- Huber 1999, p. 167.

- Huber 1999, pp. 167–168.

- Huber 1999, p. 170.

- Liegl, Markus B. (2017), China's Use of Military Force in Foreign Affairs: The Dragon Strikes, Taylor & Francis, p. 110, ISBN 978-1-315-52932-5

- Guyot-Réchard 2017, p. 186.

- Shannan Prefecture marked on OpenStreetMap, retrieved 25 January 2021. Bordering it are, in addition to Bhutan, the Tawang and East Kameng districts (then part of the Kameng Frontier Division) and the Kurung Kumey and Upper Subansiri districts (then part of the Subansiri Frontier Division).

- India, White Paper III (1960), p. 72.

- Hoffmann 1990, p. 69.

- Hoffmann 1990, p. 68.

- Hoffmann 1990, p. 68; Kavic 1967, p. 67

- Huber 1999, p. 170; Sinha & Athale 1992, p. 33

- Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Vol 51 (1972), pp. 486–489: "[Answering a question in the Parliament]: Regarding the incident at Migyitun according to their [Chinese] report, it was the Indians who fired first; the Chinese frontier guards had opened fire only in self-defence."

- Johri 1965, p. 252; Sinha & Athale 1992, p. 33; Sandhu, Shankar & Dwivedi 2015, pp. 108–109

- Johri 1965, p. 252.

- Guyot-Réchard 2017, p. 187.

- India, White Paper II (1959), pp. 7–8.

- Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Vol 51 (1972), pp. 478–489: "About a year or two ago, the Chinese had built a road from Gartok towards Yarkand, that is, Chinese Turkestan; and the report was that this road passed through a comer of our north-eastern Ladakhi territory.", "… there are two matters… an armed Chinese patrol… violated our border at Khinzemane….", "The outpost is at a place called Longju."

- Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Vol 51 (1972), pp. 486–489.

- Sandhu, Shankar & Dwivedi (2015), p. 108–109.

- Raghavan 2010, p. 253.

- Hoffmann 1990, pp. 70–71.

-

- Raghavan 2010, p. 243: "Zhou replied that China had been reprinting old maps. They had not undertaken surveys, nor consulted neighbouring countries, and had no basis for fixing the boundary lines."

- Smith, Warren W. (1996), Tibetan Nation: A history of Tibetan nationalism and Sino-Tibetan relations, Westview Press, p. 489, ISBN 978-0-8133-3155-3,

Chou had assured Nehru that the PRC was still using old KMT maps, not yet having had time to prepare their own.

- Fairbank, John King; MacFarquhar, Roderick (1987), The Cambridge History of China: The People's Republic. The emergence of revolutionary China, 1949-1965. Vol.14. Pt.1, Cambridge University Press, p. 511, ISBN 978-0-521-24336-0

- India, White Paper II (1959), p. 40: [From the letter of Chinese Prime Minister dated 8 September 1959] "The Chinese Government has consistently held that an over-all settlement of the boundary question should be sought by both sides, [taking] into account the historical background and existing actualities and adhering to the Five Principles... Pending this, as a provisional measure, the two sides should maintain the long-existing status quo of the border, and not seek to change it by unilateral action, even less by force..."

- India, White Paper II (1959), p. 50–51, item 3.

- Rose, Leo E. (1963). Conflict in the Himalayas. Institute of International Studies, University of California. pp. 7–8.: "Less than a year later the Chinese casually presented India with a new map incorporating an additional 2,000 square miles of Ladakh as Chinese territory [in Aksai Chin]. When questioned on the divergence between the two maps, Chen Yi, the Chinese Foreign Minister, made the demonstrably absurd assertion that the boundaries as marked on both maps were equally valid."

- Joshi, Manoj (7 May 2013), "Making sense of the Depsang incursion", The Hindu: 'The first is an established pattern where the PLA keeps nibbling at Indian territory to create new "facts on the ground" or a "new normal" in relation to their claimed LAC. They do this, as they have done in the past — occupy an area, then assert that it has always been part of their territory, and offer to negotiate.'

- Hoffmann (1990), p. 72; India, White Paper II (1959), p. 66–67, item 28; India, White Paper II (1959), p. 75–76 (Annexure to the letter from the Prime Minister of India to the Prime Minister of China, 26 September 1959)

- "Discussion between N.S. Khrushchev and Mao Zedong," October 02, 1959, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Archive of the President of the Russian Federation (APRF), f. 52, op. 1, d. 499, ll. 1-33, copy in Volkogonov Collection, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Translated by Vladislav M. Zubok.

- Vertzberger 1984, p. xvii–xviii.

- Sinha & Athale 1992, p. 258.

- Van Eekelen 2015, p. 220.

- Johri 1965, p. 253.

- Johri 1965, p. 253: [Quoting a Chinese memorandum] "The Indian memorandum alleges that both sides agreed that neither Chinese nor Indian personnel should occupy the village. This is pure fabrication. It is appropriate to ask: When and in what manner did the two Governments agree to refrain from 'occupying' Longju? It is impossible for the Indian Government to produce any definite evidence on the question."

- Chinese memorandum dated 8 December 1962 (India, White Paper VIII 1963, p. 60); Indian memorandum dated 19 December 1962 (India, White Paper VIII 1963, pp. 67–68)

- India, White Paper VI (1962), pp. 77–79 (Note given by the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi, to the Embassy of China in India, 28 May 1962); "Text of India reply to Chinese note, 7 June 1962". Daily Report, Foreign Radio Broadcasts, Issues 110-111. United States Central Intelligence Agency. 1962. pp. P1–P2.

- India, White Paper VI (1962), pp. 68–69 (Note given by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Peking, to the Embassy of India in China, 15 May 1962).

- Sinha & Athale 1992, p. 261: "In response to that order from Army HQ, 4 Inf Div informed [them] that the post at Maja could not be reinforced by one [Rifle Company] because no DZ [drop zone] was available in Maja area which was two days march from Lemeking, the nearest IAF approved DZ."

- Sinha & Athale 1992, p. 264.

- Johri 1965, p. 254.

- Sandhu, Shankar & Dwivedi 2015, pp. 110–111.

- India, White Paper X 1964, pp. 39–40.

- "Unprovoked Chinese intrusion into Longu area across International Border" (PDF). Press Information Bureau, Ministry of External Affairs. 13 December 1965. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "India's protest note to China" (PDF). Press Information Bureau, Ministry of External Affairs. 3 February 1966.

- Som, Vishnu (18 January 2021). "Exclusive: China Has Built Village In Arunachal, Show Satellite Images". NDTV News.

- Satellite images show Chinese building infrastructures in Arunachal, The Arunachal Times, 19 January 2021.

Bibliography

- Guyot-Réchard, Bérénice (2017). Shadow States: India, China and the Himalayas, 1910–1962. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107176799.

- Hoffmann, Steven A. (1990), India and the China Crisis, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06537-6

- Huber, Toni (1999), The Cult of Pure Crystal Mountain: Popular Pilgrimage and Visionary Landscape in Southeast Tibet, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-535313-6

- Johri, Sitaram (1965), Chinese Invasion of NEFA, Himalaya Publications

- Kavic, Lorne J. (1967), India's Quest for Security: Defence Policies, 1947-1965, University of California Press

- Mehra, Parshotam (1974), The McMahon Line and After: A Study of the Triangular Contest on India's North-eastern Frontier Between Britain, China and Tibet, 1904-47, Macmillan, ISBN 9780333157374 – via archive.org

- Mullik, Bhola Nath (1971). The Chinese Betrayal: My Years with Nehru. India: Allied Publishers – via archive.org and PAHAR.

- Raghavan, Srinath (2010), War and Peace in Modern India, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-1-137-00737-7

- Raghavan, K. N. (2017) [2012], Dividing Lines (Revised ed.), Leadstart/Platinum Press, ISBN 978-93-5201-014-1

- Rose, Leo E.; Fisher, Margaret W. (1967), The North-East Frontier Agency of India, Near and Middle Eastern Series, vol. 76, Office of Public Affairs, Department of State, LCCN 67-62084

- Sandhu, P. J. S.; Shankar, Vinay; Dwivedi, G. G. (2015), 1962: A View from the Other Side of the Hill, Vij Books India Pvt Ltd, ISBN 978-93-84464-37-0

- Sinha, P.B.; Athale, A.A. (1992), History of the Conflict with China, 1962 (PDF), History Division, Ministry of Defence, Government of India

- Van Eekelen, Willem (2015), Indian Foreign Policy and the Border Dispute with China: A New Look at Asian Relationships, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-30431-4

- Van Eekelen, Willem Frederik (1967). Indian Foreign Policy and the Border Dispute with China (Second ed.). Netherlands: Springer. ISBN 9789401765558.

- Vertzberger, Yaacov Y I (1984). Misperceptions in Foreign Policymaking: The Sino-Indian Conflict, 1959-1962. United States: Westview Press. ISBN 9780865319707.

- Primary sources

- India. Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1959), Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged and Agreements Signed Between the Governments of India and China: September - November 1959, White Paper No. II (PDF), Ministry of External Affairs

- India. Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1960), Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged and Agreements Signed Between the Governments of India and China: November 1959 - March 1960, White Paper No. III (PDF), Ministry of External Affairs

- India. Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1962), Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged and Agreements Signed Between the Governments of India and China: November 1961 - June 1962, White Paper No. VI (PDF), Ministry of External Affairs

- India. Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1962), Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged and Agreements Signed Between the Governments of India and China: July 1962 - October 1962, White Paper No. VII (PDF), Ministry of External Affairs

- India. Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1963), Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged and Agreements Signed Between the Governments of India and China: October 1962 - January 1963, White Paper No. VIII (PDF), Ministry of External Affairs

- India. Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1966), Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged and Agreements Signed Between the Governments of India and China: July 1963 - January 1964, White Paper No. X (PDF), Ministry of External Affairs – via claudearpi.net

- Kaul, B. M. (1967), The Untold Story, Allied Publishers – via archive.org

- Palat, Madhavan K., ed. (1999). Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Second Series. Vol. 51. New Delhi: Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund.

- Palat, Madhavan K., ed. (1999). Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Second Series. Vol. 52. New Delhi: Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund – via archive.org.