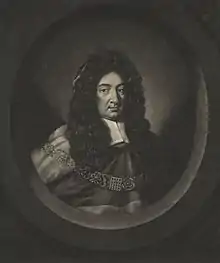

William Scroggs

Sir William Scroggs (c. 1623 – 25 October 1683) was Lord Chief Justice of England from 1678 to 1681. He is best remembered for presiding over the Popish Plot trials, where he was accused of showing bias against the accused.

Youth and early career

Scroggs was the son of an Oxford landowner; the story of him being the son of a butcher of sufficient means to give his son a university education is merely a rumour, although one which was widely believed.[1] He spent his youth in Stifford.[2] He went to Oriel College, and later to Pembroke College, Oxford, where he graduated in 1640, having acquired a fair knowledge of the classics. There is some evidence that he fought on the royalist side during the Civil War; certainly, his loyalty to the Crown was never doubted in later years. In 1653 he was called to the bar, and soon gained good practice in the courts.[3]

He was appointed a judge of the Common Pleas in 1676. Two years later he was promoted to the office of Lord Chief Justice on the recommendation of the Earl of Danby, the King's chief minister, who was his patron, and knew that he was both a good lawyer and a staunch supporter of the Crown. His hatred of Roman Catholic priests, which was to play so large a part in the Popish Plot trials, was not a fault in the eyes of Danby, who although he was the son of a Catholic mother, adhered to his father's Protestant faith. The King, although he was himself in all but outward appearance a Catholic, also accepted the need to maintain a public appearance of conformity to the Church of England, and to favour staunchly Protestant officeholders. Also, like Danby, he was anxious that the High Court judges should be good "King's men".

Scroggs on Roman Catholicism

Scroggs was noted for his violent hatred of, and public outbursts against Catholic priests, of which perhaps the most notorious was: "they eat their God, they kill their King, and saint the murderer!". His attitude towards Catholic laymen was far less hostile: even in 1678, at the height of the Plot fever, he admitted that there were hundreds of honest Catholic gentlemen in England who would never engage in any conspiracy against the King. Lay Catholics who gave evidence at the Plot trials were, in general, accorded more courtesy than were priests: at the trial of Sir George Wakeman, Ellen Rigby, the former housekeeper of the Benedictine order's house in London, was treated by Scroggs (who was reputed to be something of a misogynist) with the utmost respect.[4]

Lord Chief Justice and the Popish Plot

As Lord Chief Justice, Scroggs presided at the trial of the persons denounced by Titus Oates and other informers for complicity in the fabricated "Popish Plot", and he treated these prisoners with characteristic violence and brutality, overwhelming them with sarcasm and abuse while on their trial, and taunting them when sentencing them to death.[3] So careless was he of the rights of the accused that at one trial he admitted to the jury during his summing-up that he had forgotten much of the evidence.[5] In fairness to Scroggs, he seems to have been a sincere believer in the existence of the Plot, as was much of the general public and Parliament, but he did nothing to test the credibility of witnesses like Oates, William Bedloe, Miles Prance and Thomas Dangerfield, even though he knew well that Bedloe and Dangerfield were leading figures in the criminal underworld. He also knew that Prance had made his confession only after a threat of torture. Another leading informer, Stephen Dugdale, was arguably a case apart as he was a person of good social standing, and was generally regarded as "a man of sense and temper", with "something in his manner which disposed people to believe him". Scroggs, like many others (even the King, who was in general a complete sceptic about the veracity of the Plot), can be excused for finding his evidence credible, at least in the early stages of the Plot.

William Staley

In November 1678 William Staley, a young Catholic banker, was executed for treason, the precise charge being that he had "imagined (i.e. threatened) the King's death". Gilbert Burnet later made a violent attack on the character and credibility of William Carstares,[6] the Crown's chief witness, who testified that while dining in the Black Lion Pub in Convent Garden he had heard Staley say in French: "the King is a great heretic...this is the hand that shall kill him". His speaking in French (this was confirmed by another witness) attracted suspicion, although in fact, it was perfectly understandable since the guest he was dining with, one Monsieur Fromante, was a Frenchman. Despite Burnet's low opinion of Carstares, it is likely enough that he told the truth when he testified that Staley, who was a heavy drinker, had made this threat against the King when he was inebriated, but in less disturbed times Staley could have hoped to escape with a severe reprimand.[7] Scroggs in his summing up did tell the jury that in case of a man's life, he would have no regard paid to "the rumours and disorders of the time" but the rest of his charge was wholly in favour of a guilty verdict, which the jury duly brought in without even leaving the box. Staley was hung, drawn and quartered, but as a gesture of clemency, the Government released his body to his family for proper burial. The family unwisely had a series of requiem masses said for his soul, followed by a magnificent funeral at the Anglican St. Paul's Church, Convent Garden. The Government, infuriated, ordered that Staley's body be dug up and quartered, and his head cut off and placed on London Bridge.[8]

Edward Colman

A week later Edward Colman, former private secretary to the Duke of York, was executed for his allegedly treasonable correspondence with Louis XIV of France. Again Scroggs drove hard for a conviction, despite Colman's standing as a Government official. Colman's letters, in which he urged Louis to press Charles II for dissolution of Parliament, by bribery if necessary, showed a grave lack of political judgement, but it was straining the law very far to call them treasonable. The correspondence, which had apparently ended in 1674 or 1675, had no effect whatever on English foreign policy, and was of such little importance that Colman, until he was confronted with the letters after his arrest, had apparently forgotten writing them. Scroggs told Colman that he had been condemned on his own papers; this was fortunate for the Crown, since the evidence of Oates and Bedloe of overt acts of treason was so feeble that Scroggs in his summing-up simply ignored it.[9] Scroggs later boasted that he had hanged Colman "against the will of the Court", but in fact, it seems that the King was happy enough to sacrifice Colman, whom he had long regarded as a troublemaker.

Berry, Green and Hill

At the trial in February 1679 of the prisoners Henry Berry, Robert Green, and Lawrence Hill, accused of the murder of Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey, Scroggs gave a characteristic exhibition of his methods, indulging in a tirade against the Roman Catholic religion, and loudly proclaiming his belief in the guilt of the accused.[3] When Lawrence Hill's wife boldly accused Miles Prance, the Crown's chief witness, of perjury in open court, Scroggs said incredulously "You cannot think that he will swear three men out of their lives for nothing?".[10] All three defendants were put to death. As Mrs. Hill had correctly predicted, Prance later confessed that he had perjured himself under the threat of torture and that the three men executed were wholly innocent.

Scroggs turns against the Plot

It was only when, in July of the same year, Oates's accusation against the Queen's physician, Sir George Wakeman, appeared likely to involve the Queen herself in the ramifications of the plot, that Scroggs began to think matters were going too far; he was probably also influenced by the discovery that the Court regarded the plot with disbelief and disfavour, and that the Country Party led by Lord Shaftesbury had less influence than he had supposed with the King. The Chief Justice on this occasion threw grave doubt on the trustworthiness of Bedloe and Oates as witnesses, and warned the jury to be careful in accepting their evidence.[3] Wakeman and three priests, including the leading Benedictine Maurus Corker, who were tried with him, were duly acquitted. Scroggs for the first time observed that even a Catholic priest might be innocent of anything but being a priest (which was itself a capital crime under the Jesuits, etc. Act 1584, although Corker and the others were spared the death penalty, and were all released after spending some time in jail).[11]

This inflamed public opinion against Scroggs, for the popular belief in the plot was still strong.[3] He was accused of taking bribes from the Portuguese Ambassador, the Marquis of Arronches, acting on behalf of the Portuguese-born Queen, to secure Wakeman's acquittal. In the circumstances, the decision of the Ambassador to call on Scroggs the day after the trial to thank him for securing an acquittal has been described as an act of "incredible folly'.[12]

In August 1679 the King fell desperately ill at Windsor, and for some days his life was despaired of. Scroggs, fearing for his future, rushed to Windsor to find the King making a slow recovery: seeing Scroggs hovering anxiously in the background, the King told him that he had nothing to fear: "for we shall stand or fall together".

Scroggs continued in his poor treatment of Catholic priests who came before him for trial, as he showed when he sentenced Andrew Bromwich to death at Stafford in the summer of 1679 (although it must be said that he recommended Bromwich for mercy, and he was duly reprieved). Nevertheless, his proposing the Duke of York's health at the Lord Mayor's dinner a few months later, in the presence of Shaftesbury, indicated his determination not to support the Exclusionists against the known wishes of the King.[3] At the opening of the Michaelmas Term he delivered a speech on the need for judicial independence: "the people ought to be pleased with public justice and not justice seek to please the people... justice should flow like a mighty stream... neither for my part do I think we live in so corrupted an age that no man can with safety be just and follow his own conscience." Kenyon remarks that whatever Scroggs's faults, this speech shows that he was far more than the "brainless bully" he is sometimes portrayed as.[13]

Scroggs and Samuel Pepys

When Samuel Pepys was accused of treason, Scroggs, no doubt mindful that both Charles II and his brother the Duke of York had a high regard for Pepys, treated him with the utmost courtesy, and he never actually stood trial. As a result, the picture of Scroggs in Pepys's third diary, the so-called King's Bench Journal, is surprisingly favourable.[14] Pepys was particularly impressed by a remark of Scroggs that Pepys and his co-accused Sir Anthony Deane were Englishmen and "should have the rights of Englishmen".[15]

Scroggs had already directed the acquittal of Pepys's clerk Samuel Atkins on the charge of having conspired to murder Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey, a charge which was clearly designed to damage Pepys himself. Scroggs conducted Atkins's trial with refreshing humanity and good humour. When Atkins' alibi witness, Captain Vittles, testified that Atkins had drunk so much wine on the night in question that he could not possibly have killed anyone, Scroggs, himself a notably heavy drinker, cheerfully said: "Do you both go out and share another bottle of wine".[16]

Last years on the Bench

Acting in the assurance of popular sympathy, Oates and Bedloe now arraigned the Chief Justice before the Privy Council for having discredited their evidence and misdirected the jury in the Wakeman case, accusing him at the same time of several other misdemeanours on the bench, including a habit of excessive drinking and foul language (the charge of heavy drinking at least was probably true enough). In January 1680 the case was argued before the Council and Scroggs was acquitted. Scroggs repeated the attacks he had made on Oates' credibility at Wakeman's trial, and the King expressed his full confidence in him. At the trials of Elizabeth Cellier and of Lord Castlemaine in June of the same year, both of whom were acquitted, he discredited Dangerfield's evidence, calling him "a notorious villain ... he was in Chelmsford gaol", and on the former occasion committed the witness to prison. In the same month, he discharged the grand jury of Middlesex before the end of term in order to save the Duke of York from indictment as a popish recusant, a proceeding which the House of Commons declared to be illegal, and which was made an article in the impeachment of Scroggs in January 1681. The dissolution of Parliament put an end to the impeachment, but the King now felt secure enough to dispense with his services, and in April Scroggs, much it seems to his own surprise, was removed from the bench, although with a generous pension.[3] He retired to his country home at South Weald in Essex; he also had a townhouse at Chancery Lane in London, where he died on 25 October 1683.

Family

Scroggs married Anne Fettyplace (d. 1689[17]), daughter of Edmund Fettyplace of Berkshire: they had four children:

- Sir William Scroggs junior (died 1695), who like his father was a barrister

- Mary (died 1675)

- Anne (died 1713[18]), who married as his third wife Sir Robert Wright, who like her father became Lord Chief Justice of England but died in prison after the Glorious Revolution

- Elizabeth (died 1724), who married firstly Anthony Gylby and secondly Charles Hatton, younger son of Christopher Hatton, 1st Baron Hatton.

Scroggs' opinion of his wife, and of women in general, may perhaps be inferred from an irritable remark he made at the trial for treason of the barrister Richard Langhorne in 1679. Despite objections from William Bedloe, Scroggs permitted female observers like Mary, Lady Worcester to take notes of the evidence, on the ground that "a woman's notes will not signify, truly - no more than her tongue". On the other hand, at Wakeman's trial, he treated Ellen Rigby, the former housekeeper at the Benedictine house in London, with great respect, and told the jury to treat her evidence for the defence as credible, a tribute to her forceful personality.[19]

Personality and lifestyle

Scroggs was a judge at a time when many members of the High Court Bench were considered corrupt and unfair, and his temper and treatment of defendants were an example of the endemic problems with the judiciary, whose coarse and brutal manners shocked most educated laymen. He served on the bench during the same period as Judge Jeffreys who has been criticised for similarly poor treatment of defendants and witnesses. Kenyon notes that while their behaviour in Court seems "degrading and disgusting" by modern standards, at the time it was taken for granted: "the judges' manners were rough because they were a rough lot".[20]

Scroggs was the subject of many contemporary satires; he was reputed to live a debauched lifestyle, he was undoubtedly a heavy drinker, and his manners during trials were considered 'coarse' and 'violent'.[21]Roger North, who knew him well, described him as a man of great wit and fluency, but "scandalous, violent, intemperate and extreme". Forty years after his death, Jonathan Swift in his celebrated attack on William Whitshed, Lord Chief Justice of Ireland, called him "as vile and profligate a villain as Scroggs".

Legal writings

Scroggs was the author of a work on the Practice of Courts-Leet and Courts-Baron (published posthumously in London, 1701), and he edited reports of the state trials over which he presided.[3]

Authorities

- William Cobbett, Complete Collection of State Trials (vols. i.-x. of State Trials, 33 vols, London, 1809)

- Roger North, Life of Lord Guilford, etc., edited by A Jessopp (3 vols, London, 1890), and Examen (London, 1740)

- Narcissus Luttrell, A Brief Relation of State Affairs, 1678-1714 (6 vols, Oxford, 1857)

- Anthony à Wood, Athenae Oxonienses, edited by P Bliss (4 vols, London, 1813–1820)

- Correspondence of the Family of Hatton, edited by Edward Maunde Thompson (2 vols, Camden Society 22, 23, London, 1878)

- Lord Campbell, Lives of the Chief Justices of England (3 vols, London, 1849–1857)

- Edward Foss, The Judges of England (9 vols, London, 1848–1864)

- Sir JF Stephen, History of the Criminal Law of England (3 vols, London, 1883)

- Harry Brodribb Irving, Life of Judge Jeffreys (London, 1898).

- John Philipps Kenyon The Popish Plot Phoenix Press Reissue 2000

See also

References

- Kenyon, J.P. The Popish Plot 2nd Edition Phoenix Press London 2000 p.202

- "Parishes: Stifford | British History Online".

- McNeill 1911.

- Kenyon p.198

- Kenyon pp.184-5- Kenyon points out that a judge's summing-up was then something of an ordeal since there was no facility for taking notes, so the judge had to rely entirely on his memory of the evidence.

- Carstares is a rather shadowy figure, but he was evidently not the clergyman William Carstares, who was a prisoner in Edinburgh Castle when his namesake encountered Staley in a London tavern.

- Wild speeches by Roman Catholics were not uncommon during the reign of Charles II, but in normal times "most magistrates were sensibly content to bind the offenders over to keep the peace": Kenyon p.13

- Kenyon pp.112-3

- Kenyon pp.131-143

- Kenyon p. 166

- Kenyon pp. 192-201

- Kenyon p.202

- Kenyon p.212

- Knighton, C.S. Pepys's Later Diaries, Sutton Publishing Ltd. Gloucester 2004 p.46

- Knighton p.55

- Kenyon p.168

- Will of Dame Ann Scroggs of Saint James's Westminster, Middlesex – The National Archives. 30 October 1689.

In the name of God Amen the fifth day of July Anno D[omi]ni one thousand six hundred eighty nine [...] to my Loveing sonn S.r William Scroggs [...] to my Loveing daughter the Lady Wright twenty pounds [...] my [...] Grandchildren William Wright William Gylby Robert Gylby and Thomas Gylby [...] to my Loveing daughter M.rs Elizabeth Hatton

- "Will of Dame Anne Wright of St. Andrew Holborn in Middlesex. Probate Date: 6 May 1713". ancestry.co.uk. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

In the name of God Amen I dame Anne Wright of the Parish of St Andrews Holbourne In the County of Midd[lese]x widow make this my last will & Testament ffirst I Give & bequeath to my Son William Wright now in the Kingdom of Ireland one broad peice of gold of the value of twenty three Shillings & Sixpence Also I Give & bequeath to my Grandson Robert Wright Son of the said William Wright now at Schole at Moulton in Lincolnshire whatsoever is now or at the time of my death shall be found in my biggest Leather Trunk which s.d trunk my will is shall be delivered into the hands and possession of M.rs Elizabeth Rugg the wife of Mr Wm Rugg of Miter Court in the Temple to be by her carefully kept for the use aforesaid Also I give unto the Hon.ble Charles Hatton & his Lady to M.r W.m Gylby of Grays Inn to doct.r Robert Gray to the wife of my s.d Son W.m Wright and to Mr Edward[? or Edmund or Edmond] Burmis[?] each of them a gold Ring of ten Shillings value What money shall be found remaining in the hands of the sd M.r W.m Gylby after my debts funerall Charges and Legacies thereout paid I give the Sume to the s.d Mr W.m Gylby in Trust for my s.d Grandson Robert Wright Also all my wearing Apparel both wollen Linnen or otherwaies of Whatsoever Sort or Sorts the Same are together wth my feather bed and Pillowes as also my Scrutoe [scrutore, a writing desk or cabinet, from French escritoire] & Chest of drawers & all other matter not herein before by me bequeathed the Same I give & bequeath to my Servant Anne Boyn for her great care to me in my Sickness by her freely to be possessed and enjoyed whom I also make my only and Sole Executrix of this my last will and Testament in witness whereof I have hereunto Set my hand and Seal the Six and twentieth day of March in the year of our Lord 1713 Signed Sealed & published by the s.d dame Anne Wright as her last will & Testament in the presence of the record thereout being first undersigned C: Hatton W:Holmes [Next to the seal:] Ann Wright

- Kenyon p.198

- Kenyon p.133

- Kenyon pp. 133-4

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: McNeill, Ronald John (1911). "Scroggs, Sir William". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 484.