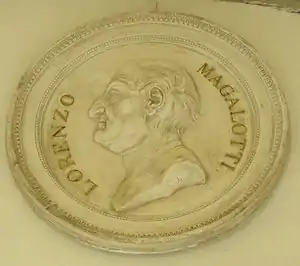

Lorenzo Magalotti

Lorenzo Magalotti (24 October 1637 – 2 March 1712) was an Italian philosopher, author, diplomat and poet.

Magalotti was born in Rome into an aristocratic family, the son of Ottavio Magalotti, Prefect of the Pontifical Mail: his uncle Lorenzo Magalotti was a member of the Roman Curia. His cousin Filippo was rector at University of Pisa. The Jesuit Magalotti became the secretary of the Accademia del cimento and a gazetteer of the sciences.[1]

Magalotti started off as one of the most ardent followers of Galileo Galilei[2] but was increasingly distressed by the personal rivalries among the individual members, which constantly undermined the academy's dedication to collective research. Gradually, Magalotti lost interest in science.[3] He became a traveller, an ambassador, and ended up as a poet. He translated Paradise Lost by John Milton, and Cyder by John Philips into Italian.

Life

Magalotti received four years of education at the Collegio Romano and three years at the University of Pisa. He studied law and medicine, but changed to mathematics under Vincenzo Viviani.[4] On 19 June 1657 the Cimento was founded by a group of philosophers and amateurs, pupils of Galilei, who saw observation as their task.[5] They studied the works of Plato, Democritus, Aristotle, Heinsius, Robert Boyle and Pierre Gassendi. The astronomers of the Cimento succeeded in providing the first sustained confirmation of Christiaan Huygens's discoveries: Saturn's rings.

.jpg.webp)

On 20 May 1660, Lorenzo Magalotti had replaced Segni, and a few years later he wrote the only publication of the academy, the Saggi di naturali Esperienze ("Essays on Natural Experiments"). Alessandro Marchetti, Marcello Malpighi, an anatomist, and Antonio Vallisneri, a physician, Vincenzo da Filicaja, Benedetto Menzini, both poets, Francesco Redi, a "microbiologist", Viviani, Giovanni Alfonso Borelli, a physicist, and Carlo Renaldini, an astronomer regularly attended its meetings. These were usually held in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence. Members performed numerous experiments, in the fields of thermometry, barometry, pneumatics, the velocity of sound and light, phosphorescence, magnetism, amber and other electrical bodies, the freezing of water, etc.

Medicine was, without doubt, the talked-about subject of the day.[6] The young Danish anatomist Niels Stensen, better known as Steno, arrived from Copenhagen by way of Leiden and Paris early in 1666. The Norman astronomer Adrien Auzout, inventor of a device for measuring planetary diameters, arrived in 1668, fresh from a quarrel with Jean-Baptiste Colbert and armed with a letter from Magalotti, who by then had become Leopoldo's main talent scout abroad.[7]

Magalotti knew as well as anyone that a scientifically valid explanation of the comet of 1664 could have made an important contribution to an explanation of the whole Solar System. But instead of attempting one, he amused himself with the obviously ridiculous thesis that the tail of the comet was an optical illusion. As soon as he saw Cassini's much more penetrating and much better-informed explanation, he admitted that he cared no more for comets than for rainbows. As early as 1664 he had been appointed to the commission charged with supervising the decoration of Palazzo Pitti and from then on, until his death he made a point of getting to know all the practising artists of the city. In 1667 Magalotti had made a pilgrimage to the blessed bones of the divine poet at Ravenna. Magalotti had met Sir John Finch and Henry Neville, he had improved his English and with his boyhood friend Paolo Falconieri, an architect, he made plans to visit Northern Europe.

Travelling to the Netherlands

The two companions left in mid-July, crossed the Alps, and arrived in Augsburg in August. By mid-October they were wandering around in the Hague and visited Heinsius, Isaac Vossius, and Jacob Gronovius. On 12 November 1667 Magalotti arrived in Utrecht to visit Johann Georg Graevius. In the meantime Cosimo III de' Medici went on his grand tour. The Grand Duke travelled in a group of 18 people and 14 carriages, accompanied by six cooks and his secretary Appolonio Bassetti. On 28 October 1667, they had arrived in Tyrol, travelled to Mainz to visit the prince-elector, and set direction down the Rhine. On 19 December they arrived in Amsterdam. On his first day he saw the Admiralty of Amsterdam and the warehouses and wharves of the Dutch East India Company. Cosimo planned to start an East India Company from Livorno. The duke took his lodgings in a house at Keizersgracht, keen on keeping a private life, living with the Tuscan merchant and slave-trader Francisco Ferroni.

While it is difficult to make out who went where with whom, and supposedly, the somewhat shy, pious, and taciturn Cosimo never went somewhere without company, an excerpt of the diary of Cosimo's visits is following here.

A patron of the arts, Cosimo visited fifteen painters over a four-month period:[8] the Leiden painters Gerard Dou and Frans van Mieris the Elder; Ludolf Bakhuizen, Willem van de Velde the Elder, Jan van Kessel, Nicolaes Maes, and Gabriel Metsu. From Caspar Netscher he bought four paintings.[9][10] The duke preferenced small paintings, obviously easier to pack. Around Christmas, he visited some hidden churches and social institutions. (A popular sight to visit was the madhouse on Kloveniersburgwal.) He met with the Jansenist Johannes van Neercassel. On 30 December 1667 Cosimo went to the Schouwburg of Van Campen, a copy of the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza. He probably saw "Medea" by Jan Vos. They did not understand a word, but it had been attractive to watch. The pit was almost empty, while no others were invited. On 12 January, he attended the prince William III of Orange, who was only 17 at that time and performed in the ballet on that evening. Johan de Witt saved Cosimo from a boring conversation with some Amsterdam burgomasters and introduced him to some nice looking young ladies. Cosimo met John Maurice, Prince of Nassau-Siegen, who had spent a long time in Dutch Brazil.

In the 17th century, many visitors came to Holland to see collections of paintings or rarities. The duke paid a visit to Gerrit van Uylenburgh, who owned part of the collection by Gerard Reynst. Dutch scientists and collectioners Franciscus Sylvius, Frederik Ruysch, Jan Swammerdam[11] and probably Theodor Kerckring and Nicolaes Witsen showed them their cabinet of curiosities. At Swammerdam, who studied all kinds of insects, and knew almost everything about bees, Cosimo was accompanied by Melchisédech Thévenot.

Cosimo, who was informed by the geologist and anatomist Niels Stensen, one of the exponents of the Counter Reformation, refused to meet to philosopher Baruch Spinoza, living in Rijnsburg, when Cosimo visited some painters, and the Hortus Botanicus Leiden.[12] He bought a painting by Jan van der Heyden, which has a strange perspective, but Van der Heyden delivered a tool to see the oval bell-tower from the right angle and in a more natural and round shape.[13] On the last day of his stay in Amsterdam he ordered a self-portrait from Rembrandt.[14] He visited Plantin House in Antwerp,[15] then they went to Mechelen, Brussels to order some tapestries and went back to the Dutch Republic.

Around Ash-Wednesday, Cosimo peregrinated via Bentheim to Hamburg. While the inns were less abundant, Cosimo spent the night in a farmhouse, where they could "talk with the cows" in the stable. The travelling became harder because of all the marshes and mud. Magalotti did not go along and went to London.

Travelling in England

He was shocked to see how much money the English spent on cock fights and how much mess was still leftover from the Great Fire of London. Bernardo Guasconi provided them with an invitation to the weekly meetings of the Royal Society. A lecture-demonstration by Robert Hooke, as well as a warm reception by the secretary, Henry Oldenburg, quickly overcame their initial disappointment in finding the society somewhat less formally organised than they had expected. Magalotti was greatly disillusioned about his reception by the King.[16] The two men made a seven-day trip to Windsor, Hampton Court, and Oxford where they visited Robert Boyle. When Magalotti became ill Boyle visited him and sat by his bedside for two or three hours daily.[17] One of the main purposes of the trip had been fully realised. Receiving courtesies from wise and learned men is ample recompense for all the trouble and money spent on travelling. And a score of prominent scholars and one real king was not a bad record for a thirty-year-old tourist of as yet no particular accomplishment.

They ended up, toward the end of April, in Paris.[18] He met Henri Louis Habert de Montmor, founder of a famous scientific salon, Jean Chapelain, a specialist on Italian literature, Valentin Conrart, and Ismael Bouillau, his scientific correspondent.[19]

Travelling to Spain and Portugal

Because Cosimo's wife, the beautiful, vivacious, headstrong and thoroughly spoiled Marguerite Louise d'Orléans was as intractable as ever, he headed on 18 September, from Livorno for another journey to Spain. Magalotti, as a member of the retinue of 27 men, was given the job of keeping a diary.[20] Magalotti promised to send catalogues and books to Antonio Magliabechi, a dirty librarian, who did not care about his looks. From Barcelona they travelled to Madrid where he spent a month; It is supposed the 8-year-old Carlos II, by then hardly able to speak and walk, received him in a private interview.[21] Then they went to Córdoba, Seville and Granada, followed by Talavera la Real and Badajoz. Magalotti found Spain to be bankrupt and demoralised, proud and lavish. Its learning hopelessly out of touch with the rest of Europe; its religion consisted largely of elaborate processions, gaudy reliquaries, and fables. None of the professors at the University of Alcalá could speak more than three words of Latin.[22]

By January, he had arrived in Lisbon via Setúbal. While Lorenzo Magalotti limits himself to offering us a general view, Filippo Corsini describes in detail the Portuguese defensive system, keeping in mind even the names of some military men who distinguished themselves in the Portuguese Restoration War. In general the Prince preferred to lodge in religious institutions and frequently chatted with the priests. It was the Monastery of Saint Denis of Odivelas that most aroused the curiosity of the Florentines. The Prince and his court left the Portuguese territory from Caminha on 1 March, travelling on a ship that would take them to Galicia, Spain.[23]

Travelling to England and the Netherlands

From La Coruňa they set off for England. Because of an uncomfortable storm they arrived in Kinsale and then headed to Plymouth. Cosimo spent three months in London where Charles II received him. Samuel Pepys described him as "a very jolly and good comely man".[24] Cosimo was amiably welcomed by the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge[24] and at Billingbear House.[25] When Billingbear House was visited by the Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1669, Magalotti painted a view of the house during the two-day stay,[26] which is one of various images to be found in an illustrated manuscript in the Laurentian Library, Florence.[27]

Count Magalotti visited Exeter, and wrote of over thirty thousand people being employed in the county of Devon as part of the wool and cloth industries, merchandise that was sold to "the West Indies, Spain, France and Italy".[28] They met the miniaturist Samuel Cooper, who painted Cosimo,[29] and John Michael Wright. Cosimo later called at Wright's studio where he commissioned a portrait of the Duke of Albemarle from Wright.

Falconieri presented to the Royal Society in London and to Charles II of England, copies of the newly printed reports of experimental science in Florence, Saggi di naturali esperienze.[30] In England he made a number of good friends, including Isaac Newton; among the over one hundred distinguished persons who came to call on him was Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore, who became his correspondent. Samuel Morland sent him a calculating machine and his loudspeaker. Cosimo became a dedicated Anglophile.[31]

On 14 June 1669, they left England and travelled to Rotterdam. He met Coenraad van Beuningen and the liberal Charles de Saint-Evremond, whose essays and poetry Magalotti was to study so attentively in later years. Cosimo picked up a few painting he had ordered. Actually, he saw Rembrandt a few months before the painter died. Then they went to Haarlem, Alkmaar, Hoorn, Enkhuizen and Molkwar, a small village, built on eight islands, connected with 27 bridges. One day they visited Delft to see some good paintings and met with the widow and nobly three daughters of Maarten Tromp.[32] (Tromp married in 1640 Cornelia van Teding Berkhout, his third wife; she died in Delft in 1680.) Via Nijmegen, Aix-la-Chapelle and Spa they moved south. Cosimo visited Louis XIV, and Marguerite of Lorraine his mother-in-law, in Paris. Via Lyon and Marseille he arrived in Florence on 1 November 1669.[33]

In his writing travelogs Magalotti was inspired by Jacob Spon and Jean Chardin.[34] He renounced the career of those who toured the world [just] to copy epitaphs and count the steps in bell towers.[35]

Ambassador in Vienna

After 1670, Florentine science changed somewhat in character. Magalotti was unsure whether many of Cosimo's projects were worth the huge sums spent by the Grand Duke. For instance, Cosimo aspired to convert England, northern Germany and India to Catholicism, batter the Ottoman Empire by land and by sea, and establish permanent commercial relations with Persia.[36] Magalotti continued his travels without the Grand Duke.

He visited Brussels, Cologne, the United Provinces, Hamburg, Copenhagen and Stockholm in 1673/1674 as a Tuscan ambassador to the Imperial court of the Holy Roman Empire in Vienna. He described in his book Sweden in the year 1674 Charles XI of Sweden as "virtually afraid of everything, uneasy to talk to foreigners, and not daring to look anyone in the face". Other traits was a deep religious devotion: he was God-fearing, frequently prayed kneeling and attended sermons. Magalotti otherwise described the king's main pursuits as hunting, the upcoming war, and jokes.

In May 1678 he went home. In 1680 his brother found him a rich widow in Naples, but he told the negotiators he had become impotent. Magalotti decided that he was better suited for some sort of intellectual activity. In 1709 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London.[37]

He died in Florence in 1712.

Works

- Historia Electrica

- Philosophia Electrica

- Saggi di naturali esperienze.[38] or Essays on Natural Experiments (1667)

References

- Conchrane, E. (1973) Florence in the Forgotten Centuries 1527–1800, p. 255.

- Conchrane, E. (1973), p. 237.

- Conchrane, E. (1973), p. 246.

- Conchrane, E. (1973), p. 231.

- Conchrane, E. (1973), p. 240.

- Conchrane, E. (1973), p. 251.

- Conchrane, E. (1973), p. 248.

- Wetering, Ernst van de (9 May 1997). "Rembrandt: The Painter at Work". Amsterdam University Press. Retrieved 9 May 2023 – via Google Books.

- Liedtke, W. (2007) Dutch Painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 512, 518.

- The cook and the lacemaker by Netscher can still be seen in the Uffizi.

- Israel, J. (1995) The Dutch Republic, Its Rise Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806. Clarendon Press Oxford, p. 877.

- Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity 1650–1750 by Jonathan Irvine Israel

- View on the town hall of Amsterdam

- Selfportrait of Rembrandt in the Uffizi Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Chapter 13 The Plantin House as a Tourist Attraction, The Golden Compasses, Leon Voet". DBNL. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- Lecture 20 incois.gov.in

- Borderlines or Interfaces in the Life and Work of Robert Boyle (1627–1691): The authorship of Protestant and Papist revisited by

D. Thorburn Burns "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Conchrane, E. (1973), p. 257.

- Conchrane, E. (1973), p. 258.

- Conchrane, E. (1973), p. 261.

- Acton, p 103

- Conchrane, E. (1973), p. 262-263.

- "e-Journal of Portuguese History".

- Acton, p 104

- Count L. Magalotti, Travels of Cosmo the Third, Grand Duke of Tuscany, through England during the Reign of King Charles the Second 1669, (J. Mawman, London, 1821), p.277.

- Billingbear Park, Waltham St. Lawrence, Berkshire", from website David Nash Ford's "Royal Berkshire History" (Accessed 13 September 2007).

- "Travels of Cosmo III". www.buildinghistory.org. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- Gray 2000, Exeter: The Traveller's Tales. p.18

- "Exhibitions". www.rct.uk. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- Susana Gomez Lopez, "The Royal Society and Post-Galilean Science in Italy" Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 51.1 (January 1997:35–44) p. 38.

- Conchrane, E. (1973), p. 262.

- Vermeer and the Delft School by Walter A. Liedtke, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.)

- Acton, p 105

- Conchrane, E. (1973), p. 264.

- Conchrane, E. (1973), p. 268.

- Conchrane, E. (1973), p. 269.

- "Library and Archive Catalogue". Royal Society. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- "Saggi di naturali esperienze: Institute and Museum of the History of Science".

Sources

- Acton, Harold: The Last Medici, Macmillan, London, 1980, ISBN 0-333-29315-0. First published in 1932, first revised edition in 1958.

- Conchrane, E. (1973) Florence in the Forgotten Centuries 1527–1800. A History of Florence and the Florentines in the Age of the Grand Dukes. Book IV Florence in the 1680s. How Lorenzo Magalotti looked in vain for a vocation and finally settled down to sniffing perfumes.

- Hoogewerff, G.J. (1919) De twee reizen van Cosimo de' Medici, prins van Toscane door de Nederlanden. (n.b. including several diaries on the trip in Italian)

- Lorenzo Magalotti at the court of Charles II: his Relazione d'Inghilterra of 1668 / Lorenzo Magalotti ; W.E. Knowles Middleton, editor & translator Lorenzo Magalotti at the Court of Charles II: His Relazione D’Inghilterra of 1668.

External links

Media related to Lorenzo Magalotti at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lorenzo Magalotti at Wikimedia Commons- Preti, Cesare; Matt, Luigi (2006). "MAGALOTTI, Lorenzo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 67: Macchi–Malaspina (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.