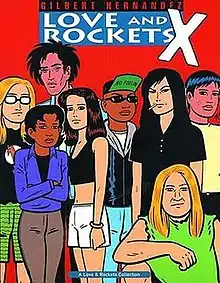

Love and Rockets X

Love and Rockets X is a graphic novel by American cartoonist Gilbert Hernandez. Its serialization ran in the comic book Love and Rockets Vol. 1 #31–39 from 1989 to 1992, and the first collected edition appeared in 1993.

The story crosses the paths of a large cast of characters from various social and ethnic groups in Los Angeles. Central is a garage rock band that calls itself Love and Rockets. The story shifts quickly from scene to scene and character to character, none of whom take the role of a central protagonist. Hernandez uses none of the magic realist elements in this work that are prominent in the Palomar stories for which he is best known.

Background and publication

Love and Rockets was an alternative comic book begun in the early 1980s[lower-alpha 1] showcasing the work of the Hernandez brothers: Mario (b. 1953), Gilbert (b. 1957), and Jaime (b. 1959),[1] who normally worked independently of each other.[2] The stories featured sensitive portrayals of prominent female and multiethnic characters—especially Latinos—which were uncommon in American comics of the time.[3] Gilbert's Palomar stories focused on the lives of a fictional Latin-American community, in particular that of the hammer-wielding bath-giver Luba, who makes her way to the center of the village's political and social life.[4]

Hernandez gradually took advantage of serialization to broaden his narrative scope;[3] the stories became longer and more ambitious, and Hernandez delved more deeply into the backgrounds of his characters,[5] their community,[6] and sociopolitical issues.[7] His longest and most complex work Poison River[8] appeared in #29–40.[9] Love and Rockets X ran alongside Poison River[10] and Jaime's eight-part Wig Wam Bam.[11]

The serialization of Love and Rockets X appeared in Love and Rockets Vol. 1 #31–39 from December 1989 to August 1992.[12] The serialization was titled Love and Rockets; the X was appended when it appeared as the title story of the tenth volume (hence "X")[13] of the tenth volume of the Complete Love and Rockets in 1993,[12] to which Hernandez added a few extra pages.[14] The collected page count comes to 96 pages.[15] In 2007 Love and Rockets X appeared in the Beyond Palomar volume of The Love and Rockets Library with Poison River.[12] Hernandez arranges the panels in either a six- or nine-panel grid, depending on the page sizes of the volume the work appears in.[16]

Synopsis

The story crosses the paths of characters from various social and ethnic groups in Los Angeles.[17] Forty of the ensemble cast have significant speaking roles, but none takes the part of the main protagonist. The story takes place in 1989, against the backdrop of the city's racial tensions of the era and the US invasion of Panama. At the nominal center is a punk band called Love and Rockets, which shares its name with the English band;[18] the punk band complains stole the name from them[19] (the real-life band formed in 1985 and took its name from the Hernandez's comic book). The band is slated to appear at a party at the bass player's upper-class mother's home, but the performance never takes place in the story. Rather, the story quickly transitions from character to character, revealing details of each one's personality traits and ethnic, class, sexual,[18] and subcultural backgrounds.[14] The story builds in complexity to a chaotic alcohol- and drug-fueled party in which someone almost gets killed; the turbulent narrative then calms and slows into a sequence of wordless panels that pan out into the cosmos.[18]

Style and analysis

The artwork is abstract and cartoony: cars speed along without touching the ground, characters' expressions are sometimes reduced to simple shapes such as large, enraged shouting mouths with jagged teeth, and dialog balloons are sometimes filled with no more than symbols.[16] Hernandez uses marginal notes to identify bands and songs played in the story[20] and to explain non-English vocabulary the book's various ethnic characters use. He uses typographical marks such as angle brackets to mark off non-English speech translated into English, such as from Spanish or Arabic.[21]

The story has none of the magic realist elements Hernandez used in the Palomar stories he is best known for.[22] The straightforward chronology and easily distinguished characters marked a contrast to those of the complicated Poison River.[10] It nevertheless shares with Poison River[20] a density that requires a relatively slow reading to follow.[13] It is condensed to quick, minimal scenes with expository dialog. The panel rather than the page is the compositional unit; each panel is of equal size, and depending on the publication the work appears in, Hernandez arranges the panels in six- or nine-panel grids.[16]

The frequent shifts from scene to scene and character to character give each character brief moments to assume the focus, while the action in the background often draws away from the reader's attention.[13] The characters each have sympathetic and deplorable sides, and Hernandez often reveals sides of the characters that contradict the stereotypes they appeared to live up to.[23]

The abrupt shifts between panels require the reader to evaluate the relations between them in a manner different from the familiar manner of closure.[lower-alpha 2][25] Comics scholar Douglas Wolk asserts Hernandez's formal concerns with "time and suggestion"[26] have a "moral weight"[26] in that they discourage the tendency to "[identify] with particular characters at the expense of others"[26] when the work's concerns lie in broader socio-political issues.[26] The copy on the first collected edition compares the book to Robert Altman's film Nashville (1975), which features a large ensemble cast and interweaving storylines.[26]

Ethnicity and ethnic relations form the central themes of the story. Several characters are of mixed ethnicities, such as a half-Jewish, half-Muslim girl infatuated with a Mexican boy, and a boy who, when asked for his ethnicity, responds, "I'm Mexican and I'm black—and I'm Chinese and Indian and Aborigine and Inuit and Jewish and Martian ..."[27] Most of the characters take part or consider taking part in inter-ethnic relations, even when they reject the idea, as in a dialogue between two African American men:[14]

- "You best remember this, son: a brother will do anything to get white pussy".

- "Firs': I ain't yo' son ... Second: fuck that Unca Tom bul'shit".

The exception is a group of white supremacists, the only characters portrayed as overwhelmingly negative—though Hernandez gives even these characters a pre-racist past that other characters lament the loss of.[15]

The story often delves into the characters' sexuality, including homosexual relations such as that of Riri and Maricela, the daughter of Luba, one of the central characters in Hernandez's Palomar stories.[27] The pair have run away from Palomar, where Maricela had endured physical abuse from her mother,[19] and where the pair had to hide their relationship. In the US they are freer to express their affections openly, but must instead hide their illegal immigrant status and avoid la migra (the immigration authorities), another theme that runs through the book.[5] The Los Angeles setting and themes of punk rock and ethnic and sexual relations are central in the Locas stories of Hernandez's brother Jaime as well.[20]

F. Vance Neill sees the book as a "critique of the disintegration of community",[22] in which the characters are self-absorbed; each, as Wolk sees it, "believe that they're its hero".[28] To Neill, Hernandez underlines this in the closing sequence in which he "shuts down narrative development and isolates each character to one panel apiece",[22] an ending that "indicates a shattering of the relationships between people"[22] and "reiterates the importance of the values of la familia, acceptance of identity, integrity, the normalcy of the supernatural, and the sanctity of secrets".[22] Wolk interprets this ending in the context of quickly shifting scenes of the rest of the work—that it requires readers to slow down and think about the sequence of events and their contexts and interrelations.[29]

Aside from Riri and Maricela,[27] other characters from earlier Hernandez works include the unnamed "dudes" who made minor appearances as tourists in Palomar in Human Diastrophism (1989)[5] and Fritz the psychiatrist from the erotic Birdland (1992).[30]

Reception and legacy

On its release, reviewer Anne Rubenstein praised Love and Rockets X for expanding the "aesthetic possibilities of the graphic narrative"; she recommended it as a starting point for new Love and Rockets readers daunted by the complexity of the earlier stories, and called it "as essential as the rest of the Hernandez canon".[14] Comics critic R. Fiore placed Love and Rockets X 7th on his list of best English non-strip comics of the 1990s. He calls it "a comics equivalent of a Victor Hugo-style social novel" and praises Hernandez for successfully interweaving so many of the quasi-isolated ethnic social milieus of Los Angeles into one narrative, though he found weakness in Hernandez's grasp of their various speech patterns and suggested actual South Americans would have been more appropriate to the real political background than the fictional Palomarians.[17] Reviewer Tom Knapp considered the work "confusing" and "one of the low points" in the Love and Rockets series.[19]

Douglas Wolk called Love and Rockets X "the prime example of Gilbert's fascinations as a storyteller".[13] F. Vance Neill saw it as an early example of Hernandez's concern with "the values of trust, loyalty, honesty, and community"[22] and "the consequences of failing to adhere to these values"[22] that he explored later in works such as Speak of the Devil (2008) and The Troublemakers (2009).[22] The story's Los Angeles setting anticipated that of Hernandez's post-Palomar stories featuring Luba and her family.[20]

Notes

- The first self-published issue appeared in 1981; the first Fantagraphics issue from 1982 is an expanded reprint of the self-published issue.

- "Closure" in this sense is a term Scott McCloud introduced in Understanding Comics (1993) to refer to reader's role in closing narrative gaps between comics panels.[24]

References

- Hatfield 2005, p. 68; Royal 2009, p. 262.

- Creekmur 2010, p. 282.

- Hatfield 2005, p. 69.

- Knapp 2001.

- Glaser 2013.

- Hatfield 2005, pp. 71.

- Hatfield 2005, pp. 68–69.

- Pizzino 2013.

- Royal 2009, p. 262.

- Rubenstein 1994b, p. 48.

- Hatfield 2005, p. 102.

- Royal 2013b.

- Wolk 2008, p. 185.

- Rubenstein 1994a, p. 52.

- Rubenstein 1994a, p. 53.

- Wolk 2008, p. 188.

- Fiore 1997, p. 70.

- Wolk 2008, pp. 185–186.

- Knapp 2004.

- Royal 2013a.

- Aldama 2012, p. 90.

- Neill 2013.

- Wolk 2008, pp. 186–187.

- Hatfield 2005, p. 70.

- Wolk 2008, p. 191.

- Wolk 2008, p. 192.

- Wolk 2008, p. 187.

- Neill 2013; Wolk 2008, p. 186.

- Neill 2013; Wolk 2008, pp. 191–192.

- Wolk 2008, p. 189.

Works cited

- Aldama, Frederick Luis (2012). Your Brain on Latino Comics: From Gus Arriola to Los Bros Hernandez. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-74991-7 – via Project MUSE.

- Creekmur, Corey K. (2010). "Hernandez Brothers". In Booker, M. Keith (ed.). Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 282–283. ISBN 978-0-313-35748-0.

- Fiore, R. (December 1997). Groth, Gary (ed.). "A Nice German Trench". The Comics Journal. Fantagraphics Books (200): 67–71. ISSN 0194-7869.

- Glaser, Jennifer (2013). "Picturing the Transnational in Palomar: Gilbert Hernandez and the Comics of the Borderlands". ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies. University of Florida. 7 (1). ISSN 1549-6732. Retrieved 2014-11-29.

- Hatfield, Charles (2005). "Gilbert Hernandez's Heartbreak Soup". Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 68–107. ISBN 978-1-57806-719-0. Retrieved 2012-09-19 – via Project MUSE.

- Knapp, Tom (2001-08-10). "Love & Rockets #12: Poison River". Rambles. Retrieved 2012-09-19.

- Knapp, Tom (2004-04-25). "Love & Rockets #10: X". Rambles. Archived from the original on 2004-06-29. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- Neill, F. Vance (2013). "Gilbert Hernandez as a Rhetor". ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies. University of Florida. 7 (1). ISSN 1549-6732. Retrieved 2014-11-29.

- Pizzino, Christopher (2013). "Autoclastic Icons: Bloodletting and Burning in Gilbert Hernandez's Palomar". ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies. University of Florida. 7 (1).

- Royal, Derek Parker (Spring 2009). "To Be Continued...: Serialization and its Discontent in the Recent Comics of Gilbert Hernandez". International Journal of Comic Art: 262–280.

- Royal, Derek Parker (2013a). "The Worlds of the Hernandez Brothers". ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies. University of Florida. 7 (1). ISSN 1549-6732. Retrieved 2014-11-29.

- Royal, Derek Parker (2013b). "Hernandez Brothers: A Selected Bibliography". ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies. University of Florida. 7 (1). ISSN 1549-6732. Retrieved 2014-11-29.

- Rubenstein, Anne (May 1994). Groth, Gary (ed.). "Stirring the Melting Pot: Love and Rockets X". The Comics Journal. Fantagraphics Books (168): 52–53. ISSN 0194-7869.

- Rubenstein, Anne (November 1994). "Difficult Pleasures: Poison River". The Comics Journal. Fantagraphics Books (172): 47–48. ISSN 0194-7869.

- Wolk, Douglas (2008). Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-7867-2157-3.