Siege of Lucknow

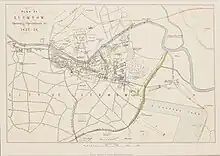

The siege of Lucknow was the prolonged defence of the British Residency within the city of Lucknow from rebel sepoys (Indian soldiers in the British East India Company's Army) during the Indian Rebellion of 1857. After two successive relief attempts had reached the city, the defenders and civilians were evacuated from the Residency, which was then abandoned.

| Siege of Lucknow | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Indian Rebellion of 1857 | |||||||

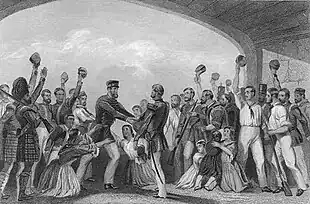

The Relief of Lucknow, by Thomas Jones Barker | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Various commanders including: | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,729 troops, rising to approx. 8,000 | 5,000 men, rising to approx. 30,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,500 killed, wounded, missing | unknown | ||||||

Background to the siege

The state of Oudh/Awadh had been annexed by the British East India Company and the Nawab Wajid Ali Shah was exiled to Calcutta the year before the rebellion broke out. This high-handed action by the East India Company was greatly resented within the state and elsewhere in India. The first British Commissioner (in effect the governor) appointed to the newly acquired territory was Coverley Jackson. He behaved tactlessly, and Sir Henry Lawrence, a very experienced administrator, took up the appointment only six weeks before the rebellion broke out.

The sepoys of the East India Company's Bengal Presidency Army had become increasingly troubled over the preceding years, feeling that their religion and customs were under threat from the evangelising activities of the Company. Lawrence was well aware of the rebellious mood of the Indian troops under his command (which included several units of Oudh Irregulars, recruited from the former army of the state of Oudh). On 18 April, he warned the Governor General, Lord Canning, of some of the manifestations of discontent, and asked permission to transfer certain rebellious corps to another province.

The flashpoint of the rebellion was the introduction of the Enfield rifle; the cartridges for this weapon were believed to be greased with a mixture of beef and pork fat, which was felt would defile both Hindu and Muslim Indian soldiers. On 1 May, the 7th Oudh Irregular Infantry refused to bite the cartridge, and on 3 May they were disarmed by other regiments.

On 10 May, the Indian soldiers at Meerut broke into open rebellion, and marched on Delhi. When news of this reached Lucknow, Lawrence recognised the gravity of the crisis and summoned from their homes two sets of pensioners, one of sepoys and one of artillerymen, to whose loyalty, and to that of the Sikh and some Hindu sepoys, the successful defence of the Residency was largely due.

Rebellion begins

On 23 May, Lawrence began fortifying the Residency and laying in supplies for a siege; large numbers of British civilians made their way there from outlying districts. On 30 May (the Muslim festival of Eid ul-Fitr), most of the Oudh and Bengal troops at Lucknow broke into open rebellion. In addition to his locally recruited pensioners, Lawrence also had the bulk of the British 32nd Regiment of Foot available, and they were able to drive the rebels away from the city.

On 4 June, there was a rebellion at Sitapur, a large and important station 51 miles (82 km) from Lucknow. This was followed by another at Faizabad, one of the most important cities in the province, and outbreaks at Daryabad, Sultanpur and Salon. Thus, in the course of ten days, British authority in Oudh practically evaporated.

On 30 June, Lawrence learned that the rebels were gathering north of Lucknow and ordered a reconnaissance in force, despite the available intelligence being of poor quality. Although he had comparatively little military experience, Lawrence led the expedition himself. The expedition was not very well organised. The troops were forced to march without food or adequate water during the hottest part of the day at the height of summer, and at the Battle of Chinhat they met a well-organised rebel force, led by Barkat Ahmad with cavalry and dug-in artillery. Whilst they were under attack, some of Lawrence's sepoys and Indian artillerymen defected to the rebels, overturning their guns and cutting the traces.[1] His exhausted British soldiers retreated in disorder. Some died of heatstroke within sight of the Residency.

Lieutenant William George Cubitt, 13th Native Infantry, was awarded the Victoria Cross several years later, for his act of saving the lives of three men of the 32nd Regiment of Foot during the retreat. His was not a unique action; sepoys loyal to the British, especially those of the 13th Native Infantry, saved many British soldiers, even at the cost of abandoning their own wounded men, who were hacked to pieces by rebel sepoys.

As a result of the defeat, the detached turreted building, Machchhi Bhawan (Muchee Bowan), which contained 200 barrels (~27 t) of gunpowder and a large supply of ball cartridge, was blown up and the detachment withdrew to the Residency.[1]

Initial attacks

Lawrence retreated into the Residency, where the siege now began, with the Residency as the centre of the defences. The actual defended line was based on six detached smaller buildings and four entrenched batteries. The position covered some 60 acres (240,000 m2) of ground, and the garrison (855 British officers and soldiers, 712 Indians, 153 civilian volunteers, with 1,280 non-combatants, including hundreds of women and children) was too small to defend it effectively against a properly prepared and supported attack. Also, the Residency lay in the midst of several palaces, mosques and administrative buildings, as Lucknow had been the royal capital of Oudh for many years. Lawrence initially refused permission for these to be demolished, urging his engineers to "spare the holy places". During the siege, they provided good vantage points and cover for rebel sharpshooters and artillery.

One of the first bombardments following the beginning of the siege, on 30 June, caused a civilian to be trapped by a falling roof. Corporal William Oxenham of the 32nd Foot saved him while under intense musket and cannon fire, and was later awarded the Victoria Cross. The first attack was repulsed on 1 July. The next day, Lawrence was fatally wounded by a shell, dying on 4 July. Colonel John Inglis of the 32nd Regiment took military command of the garrison.[2] Major John Banks was appointed the acting Civil Commissioner by Lawrence. When Banks was killed by a sniper a short time later, Inglis assumed overall command.

About 8,000 sepoys who had joined the rebellion and several hundred retainers of local landowners surrounded the Residency. They had some modern guns and also some older pieces which fired all sorts of improvised missiles. There were several determined attempts to storm the defences during the first weeks of the siege, but the rebels lacked a unified command able to coordinate all the besieging forces.

The defenders, their number constantly reduced by military action as well as disease, were able to repulse all attempts to overwhelm them. On 5 August a rebel mine was foiled; counter mining and offensive mining against two buildings brought successful results.[2] Several sorties were mounted, attempting to reduce the effectiveness of the most dangerous rebel positions and to silence some of their guns. The Victoria Cross was awarded to several participants in these sorties: Captain Samuel Hill Lawrence and Private William Dowling of the 32nd Foot and Captain Robert Hope Moncrieff Aitken of the 13th Native Infantry.

First relief attempt

On 16 July, a force under Major General Henry Havelock recaptured Cawnpore, 48 miles (77 km) from Lucknow. On 20 July, he decided to attempt to relieve Lucknow, but it took six days to ferry his force of 1500 men across the Ganges River. On 29 July, Havelock won a battle at Unnao, but casualties, disease and heatstroke reduced his force to 850 effectives, and he fell back.

Havelock managed to get a spy through to the Residency, telling them that 2 rockets would be fired at a certain time on the night when the relief force was ready to attack.[3]

There followed a sharp exchange of letters between Havelock and the insolent Brigadier James Neill who was left in charge at Cawnpore.[4] Havelock eventually received 257 reinforcements and some more guns, and tried again to advance. He won another victory near Unao on 4 August, but was once again too weak to continue the advance, and retired.

Havelock intended to remain on the north bank of the Ganges, inside Oudh, and thereby prevent the large force of rebels which had been facing him from joining the siege of the Residency, but on 11 August, Neill reported that Cawnpore was threatened. To allow himself to retreat without being attacked from behind, Havelock marched again to Unao and won a third victory there. He then fell back across the Ganges, and destroyed the newly completed bridge. On 16 August, he defeated a rebel force at Bithur, disposing of the threat to Cawnpore.

Havelock's retreat was tactically necessary, but caused the rebellion in Oudh to become a national revolt, as previously uncommitted landowners joined the rebels.

First relief of Lucknow

Havelock had been superseded in command by Major General Sir James Outram. Before Outram arrived at Cawnpore, Havelock made preparations for another relief attempt. He had earlier sent a letter to Inglis in the Residency, suggesting he cut his way out and make for Cawnpore. Inglis replied that he had too few effective troops and too many sick, wounded and non-combatants to make such an attempt. He also pleaded for urgent assistance. The rebels meanwhile continued to shell the garrison in the Residency, and also dug mines beneath the defences, which destroyed several posts. Although the garrison kept the rebels at a distance with sorties and counter-attacks, they were becoming weaker and food was running short.

Outram arrived at Cawnpore with reinforcements on 15 September. He allowed Havelock to command the relief force, accompanying it nominally as a volunteer until Lucknow was reached. The force numbered 3,179 and was composed of six British and one Sikh infantry battalions, with three artillery batteries, but only 168 volunteer cavalry. They were divided into two brigades, under Neill and Colonel Hamilton of the 78th Highlanders.

The advance resumed on 18 September. This time, the rebels did not make any serious stand in the open country, even failing to destroy some vital bridges. On 23 September, Havelock's force drove the rebels from the Alambagh, a walled park four miles south of the Residency. Leaving the baggage with a small force in the Alambagh, he began the final advance on 25 September. Because of the monsoon rains, much of the open ground around the city was flooded or waterlogged, preventing the British making any outflanking moves and forcing them to make a direct advance through part of the city.

The force met heavy resistance trying to cross the Charbagh Canal, but succeeded after nine out of ten men of a forlorn hope were killed storming a bridge. They then turned to their right, following the west bank of the canal. The 78th Highlanders took a wrong turning, but were able to capture a rebel battery near the Qaisarbagh palace, before finding their way back to the main force. After further heavy fighting, by nightfall the force had reached the Machchhi Bhawan. Outram proposed to halt and contact the defenders of the Residency by tunnelling and mining through the intervening buildings, but Havelock insisted on an immediate advance. (He feared that the defenders of the Residency were so weakened that they might still be overwhelmed by a last-minute rebel attack.) The advance was made through heavily defended narrow lanes. Neill was one of those killed by rebel musket fire. In all, the relief force lost 535 men out of 2000, incurred mainly in this last rush.

By the time of the relief, the defenders of the Residency had endured a siege of 87 days, and were reduced to 982 fighting personnel.

Second siege

Originally, Outram had intended to evacuate the Residency, but the heavy losses incurred during the final advance made it impossible to remove all the sick and wounded and non-combatants. Another factor which influenced Outram's decision to remain in Lucknow was the discovery of a large stock of supplies beneath the Residency, sufficient to maintain the garrison for two months. Lawrence had laid in the stores, but died before he had informed any of his subordinates (Inglis had feared that starvation was imminent).

Instead, the defended area was enlarged. Under Outram's overall command, Inglis took charge of the original Residency area, and Havelock occupied and defended the palaces (the Farhat Baksh and Chuttur Munzil) and other buildings east of it. Outram had hoped that the relief would also demoralise the rebels, but was disappointed. For the next six weeks, the rebels continued to subject the defenders to musket and artillery fire, and dug a series of mines beneath them. The defenders replied with sorties, as before, and dug counter-mines. Twenty-one shafts were sunk and 3,291 feet of gallery were constructed by the defenders. The rebels dug 20 mines: three caused loss of life, two did no injury, seven were blown in, and seven were tunnelled into and their galleries taken over.[3]

The defenders were able to send messengers to and from the Alambagh, from where in turn messengers could reach Cawnpore. (Later, a semaphore system made the risky business of sending messengers between the Residency and the Alambagh unnecessary.) A volunteer civil servant, Thomas Henry Kavanagh, the son of a British soldier, disguised himself as a sepoy and ventured from the Residency aided by a local man named Kananji Lal. He and his scout crossed the entrenchments east of the city and reached the Alambagh to act as a guide to the next relief attempt. For this action, Kavanagh was awarded the Victoria Cross and was the first civilian in British history to be honoured with such an award for action during a military conflict.

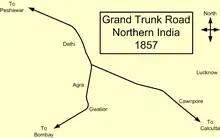

Preparations for second relief

The rebellion had involved a very wide stretch of territory in northern India. Large numbers of rebels had flocked to Delhi, where they proclaimed the restoration of the Mughal Empire under Bahadur Shah II. A British army besieged the city from the first week in June. On 10 September, they launched a storming attempt, and by 21 September they had captured the city. On 24 September, a column of 2,790 British, Sikh and Punjabi troops under Colonel Greathed of the 8th (The King's) Regiment of Foot marched through the Lahore Gate to restore British rule from Delhi to Cawnpore. On 9 October, Greathed received urgent calls for help from a British garrison in the Red Fort at Agra. He diverted his force to Agra, to find the rebels had apparently retreated. While his force rested, they were surprised and attacked by the rebel force, which had been close by. Nevertheless, they rallied, defeated and dispersed the rebel force. This Battle of Agra cleared all organised rebel forces from the area between Delhi and Cawnpore, although guerrilla bands remained.

Shortly afterwards, Greathed received reinforcements from Delhi, and was superseded in command by Major General James Hope Grant. Grant reached Cawnpore late in October, where he received orders from the new commander-in-chief in India, Sir Colin Campbell, to proceed to the Alambagh, and transport the sick and wounded to Cawnpore. He was also strictly enjoined not to commit himself to any relief of Lucknow until Campbell himself arrived.

Campbell was 64 years old when he left England in July 1857 to assume command of the Bengal Army. By mid-August, he was in Calcutta preparing his departure upcountry. It was late October before all preparations were completed. Fighting his way up the Grand Trunk Road, Campbell arrived in Cawnpore on 3 November. The rebels held effective control of large parts of the countryside. Campbell considered, but rejected, securing the countryside before launching his relief of Lucknow. The massacre of British women and children following the capitulation of Cawnpore was still in recent memory. In British eyes, Lucknow had become a symbol of their resolve. Accordingly, Campbell left 1,100 troops in Cawnpore for its defence, leading 600 cavalry, 3,500 infantry and 42 guns to the Alambagh, in what Samuel Smiles described as an example of the "women and children first" protocol being applied.[5]

British warships were dispatched from Hong Kong to Calcutta. The marines and sailors of the Shannon, Pearl and Sanspareil formed a Naval Brigade with the ships' guns (8-inch guns and 24-pounder howitzers) and fought their way from Calcutta until they met up with Campbell's force.

The strength of the rebels investing Lucknow has been widely estimated from 30,000 to 60,000. They were amply equipped, the sepoy regiments among them were well trained, and they had improved their defences in response to Havelock's and Outram's first relief of the Residency. The Charbagh Bridge used by Havelock and Outram just north of the Alambagh had been fortified. The Charbagh Canal from the Dilkusha Bridge to the Charbagh Bridge was dammed and flooded to prevent troops or heavy guns fording it. Cannon emplaced in entrenchments north of the Gumti River not only daily bombarded the besieged Residency but also enfiladed the only viable relief path. However, the lack of a unified command structure among the sepoys diminished the value of their superior numbers and strategic positions.

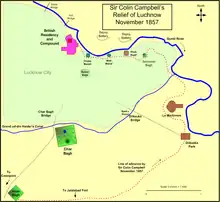

Second relief

At daybreak on 14 November, Campbell commenced his relief of Lucknow. He had made his plans on the basis of Kavanagh's information and the heavy loss of life experienced by the first Lucknow relief column. Rather than crossing the Charbagh Bridge and fighting through the tortuous, narrow streets of Lucknow, Campbell opted to make a flanking march to the east and proceed to Dilkusha Park. He would then advance to La Martinière (a school for British and Anglo-Indian boys) and cross the canal as close to the River Gumti as possible. As he advanced, he would secure each position to protect his communications and supply train back to the Alambagh. He would then secure a walled enclosure known as the Secundrabagh and link up with the Residency, whose outer perimeter had been extended by Havelock and Outram to the Chuttur Munzil.

For 3 miles (4.8 km) as the column moved to the east of the Alambagh, no opposition was encountered. When the relief column reached the Dilkusha park wall, the quiet ended with an outburst of musket fire. British cavalry and artillery quickly pushed past the park wall, driving the sepoys from the Dilkusha park. The column then advanced to La Martinière. By noon, the Dilkusha and La Martinière were in British hands.[6] The defending sepoys vigorously attacked the British left flank from the Bank's House, but the British counter-attacked and drove them back into Lucknow.

The rapid advance of Campbell's column placed it far ahead of its supply caravan. The advance paused until the required stores of food, ammunition and medical equipment were brought forward. The request for additional ammunition from the Alambagh further delayed the relief column's march. On the evening of 15 November, the Residency was signalled by semaphore, "Advance tomorrow."

The next day, the relief column advanced from La Martinière to the northern point where the canal meets the Gumti River. The damming of the canal to flood the area beneath the Dilkuska Bridge had left the canal dry at the crossing point. The column and guns advanced forward and then turned sharp left to Secundra Bagh.

Storming of Secundra Bagh

The Secundra Bagh is a high-walled garden approximately 120 yards square, with parapets at each corner and a main entry gate arch on the southern wall. Campbell's column approached along a road that ran parallel to the eastern wall of the garden. The advancing column of infantry, cavalry and artillery had difficulty manoeuvering in the cramped village streets. They were afforded some protection from the intense fire raining down on them by a high road embankment that faced the garden. Musket fire came from loopholes in the Secundra Bagh and nearby fortified cottages, and cannon shot from the distant Kaisarbagh (the former King of Oudh's palace). Campbell positioned artillery to suppress this incoming fire. Heavy 18-pounder artillery was also hauled by rope and hand over the steep road embankment and placed within 60 yards (55 m) of the enclosure. Although significant British casualties were sustained in these manoeuvres, the cannon fire breached the southeastern wall.

Elements of the Scottish 93rd Highlanders and 4th Punjab Infantry Regiment rushed forward. Finding the breach too small to accommodate the mass of troops, the Punjab Infantry moved to the left and overran the defences at the main garden gateway. Once inside, the Punjabis, many of whom were Sikhs, emptied their muskets and resorted to the bayonet. Sepoys responded with counter-attacks. Highlanders pouring in by the breach shouted, "Remember Cawnpore!" Gradually the din of battle waned. The dwindling force of defenders moved northward until retreat was no longer possible. The British numbered the sepoy dead at nearly 2000.

Storming of the Shah Najaf

By late noon, a detachment of the relief column led by Adrian Hope disengaged from the Secundra Bagh and moved towards the Shah Najaf. The Shah Najaf, a walled mosque, is the mausoleum of Ghazi-ud-Din Haider, the first king of Oudh in 1814. The defenders had heavily fortified this multi-story position. When the full force of the British column was brought to bear on the Shah Najaf, the sepoys responded with unrelenting musketry, cannon grape shot and supporting cannon fire from the Kaisarbagh, as well as oblique cannon fire from secured batteries north of the Gumti River. From heavily exposed positions, for three hours the British directed strong cannon fire on the stout walls of the Shah Najaf. The walls remained unscathed, the sepoy fire was unrelenting and British losses mounted. Additional British assaults failed, with heavy losses.

However, retiring from their exposed positions was deemed equally dangerous by the British command. Fifty Highlanders were dispatched to seek an alternate access route to the Shah Najaf. Discovering a breach in the wall on the opposite side of the fighting, sappers were brought forward to widen the breach. The small advance party pushed through the opening, crossed the courtyard and opened the main gates. Seeing the long sought opening, their comrades rushed forth into the Shah Najaf. Campbell made his headquarters in the Shah Najaf by nightfall.

Residency reached

Within the besieged residency, Havelock and Outram completed their preparations to link up with Campbell's column. Positioned in the Chuttur Munzil, they executed their plan to blow open the outer walls of the garden once they could see that the Secundra Bagh was in Campbell's hands.

The Moti Mahal, the last major position that separated the two British forces, was cleared by charges from Campbell's column. Only an open space of 450 yards (410 m) now separated the two forces. Outram, Havelock and some other officers ran across the space to confer with Campbell, before returning. Stubborn resistance continued as the sepoys defended their remaining positions, but repeated efforts by the British cleared these last pockets of resistance. The second relief column had reached the Residency.

The evacuation

Although Outram and Havelock both recommended storming the Kaisarbagh palace to secure the British position, Campbell knew that other rebel forces were threatening Cawnpore and other cities held by the British, and he ordered Lucknow to be abandoned. The evacuation began on 19 November. While Campbell's artillery bombarded the Kaisarbagh to deceive the rebels that an assault on it was imminent, canvas screens were erected to shield the open space from the rebels' view. The women, children and sick and wounded made their way to the Dilkusha Park under cover of these screens, some in a variety of carriages or on litters, others on foot. Over the next two days, Outram spiked his guns and withdrew after them.

At the Dilkusha Park, Havelock died (of a sudden attack of dysentery) on 24 November. The entire army and convoy now moved to the Alambagh. Campbell left Outram with 4,000 men to defend the Alambagh,[7] while he himself moved with 3,000 men and most of the civilians to Cawnpore on 27 November.

Aftermath

The first siege had lasted 87 days, the second siege a further 61.

The rebels were left in control of Lucknow over the following winter, but were prevented from undertaking any other operations by their own lack of unity and by Outram's hold on Alambagh, which was easily defended. Campbell returned to retake Lucknow, with the attack starting on 6 March. By 21 March 1858 all fighting had ceased.[8]

During the siege, the Union Jack had flown day and night (against the usual practice, which is to strike national flags at dusk), as it was nailed to the flagpole. After the British re-took control of Lucknow, by special dispensation (unique within the British Empire), the Union Jack was flown 24 hours a day on the Residency's flagpole, for the rest of the time the British held India. The day before India became independent, the flag was lowered, the flagpole cut down, and the base removed and cemented over, to prevent any other flag from ever being flown there.[9]

The largest number of Victoria Crosses awarded in a single day was the 24 earned on 16 November, during the second relief,[10] the bulk of these being for the assault on the Secundrabagh. Among the recipients was William Hall, a Black Nova Scotian, for manning a gun at the Shah Najaf action despite the loss of all but one of his crew mates.

The Indian Mutiny Medal had three clasps relating to Lucknow:

- Defence of Lucknow, awarded to the original defenders - 29 June to 22 November 1857

- Relief of Lucknow, awarded to the relief force - November 1857

- Lucknow, awarded to troops in the final capture of Lucknow - November 1857

Representation in popular culture

- The Relief of Lucknow was a silent film, filmed in 1911 at Prospect Camp, St. George's Town and other locations in Bermuda by the Edison Company and released in 1912.[11][12]

- The siege, with significant differences, was fictionalised in J. G. Farrell's The Siege of Krishnapur. He made extensive use of memoirs and journals of survivors of the Siege, such as those of Mrs Julia Inglis and Mrs Maria Germon.

- Dion Boucicault's Jessie Brown or the Relief of Lucknow was a play written immediately after the events and was very popular in the theatre, playing for twenty years.

- Maxwell Gray's 1891 In the Heart of the Storm is set partially in Lucknow during the siege.

- G. A. Henty's In Times of Peril and George MacDonald Fraser's Flashman in the Great Game also contain lengthy scenes set in the Residency during the siege.

- Mark Twain's non-fiction book Following the Equator devotes an entire chapter to the rebellion, quoting extensively from Sir G. O. Trevelyan.

- M. M. Kaye's Shadow of the Moon (copyright 1956/1979) is a fictional account of the last days of East India Company rule in India with many scenes set in Lucknow and environs. Most of the latter part of the book is set in Lucknow during the Siege.

- The plot of Philip Pullman's Ruby in the Smoke relies heavily on fictional events that supposedly occurred during the siege.

- Anurag Kumar's Recalcitrance is mostly based on the part played by commoners during the siege. It describes the siege as well as the final relief. It is almost entirely based on the events in Lucknow. It also describes the part played by Raja Jai Lal Singh, a commander of revolutionary forces whose contributions were highlighted for the first time by the author through newspaper articles. His contributions caused a memorial park to be built around the place where this mysterious revolutionary soldier was hanged at the end of the Great Uprising of 1857. The novel was first published in 2008 to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the mutiny.

- Valerie Fitzgerald's novel Zemindar is set in the lead up to and siege of Lucknow with the evacuation, seen from perspective of women in the Residency.[13]

- In the British television series Downton Abbey (Season 2, Episode 1), the Dowager Countess, Violet Crawley, tells her granddaughter during World War I, "War deals out strange tasks. Remember your great-aunt Roberta...She loaded the guns at Lucknow."

- The arrival of the second relief force is the subject of "The Relief of Lucknow", by Robert Traill Spence Lowell.[14]

- William McGonagall's poem The Capture of Lucknow also describes the events of the second relief.[15]

- The 1981 Indian film Umrao Jaan depicts the siege from the perspective of a nautch dancer in Lucknow.

- Alfred Lord Tennyson's The Defense of Lucknow presents the whole narrative from the imperialist point of view.

References

Footnotes

- Porter, 1889, p484

- Porter, 1889, p485

- Porter, 1889, p486

- Edwardes (1963), pp.81-81

- Smiles, Samuel (1859). Self-Help; with Illustrations of Character and Conduct. ISBN 1-4068-2123-3. 1897 edition at Project Gutenberg

- Porter, 1889, p487

- Porter, 1889, p489

- Porter, 1889, p493

- "The Last Flag". The Indian Express. 15 August 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Collections search | Imperial War Museums". Collections.iwm.org.uk. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- RELIEF OF LUCKNOW. Colonial Film

- Relief of Lucknow. IMDB

- Fitzgerald, Valerie (2014) [1981]. Zemindar. London: Head of Zeus. ISBN 9781781859537. OCLC 8751836.

- Lowell, Robert Traill Spence (1880). "The Relief of Lucknow". In Emerson, Ralph Waldo (ed.). Parnassus: An Anthology of Poetry. Bartleby.com. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- McGonagall, William (1885). "The Capture of Lucknow". McGonagall Online.

Bibliography

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Indian Mutiny, The". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Edwardes, Michael, Battles of the Indian Mutiny, Pan, 1963, ISBN 0-330-02524-4

- Forbes-Mitchell, William. The Relief of Lucknow. London: Folio Society, 1962. OCLC 200654

- Forrest, G. W., A History of the Indian Mutiny Volumes 1–3, Edinburgh and London: William Black and Son, 1904, reprinted 2006, ISBN 978-81-206-1999-9 and ISBN 978-81-206-2001-8

- Greenwood, Adrian (2015). Victoria's Scottish Lion: The Life of Colin Campbell, Lord Clyde. UK: History Press. p. 496. ISBN 978-0-75095-685-7.

- Hibbert, Christopher, The Great Mutiny, Christopher Hibbert, Penguin, 1978, ISBN 0-14-004752-2

- Porter, Maj Gen Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers Vol I. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers.

- Wolseley, Field Marshal Viscount, Story of a Soldier's Life Volume 1, London: Archibald Constable & Company 1903

Further reading

| Library resources about Siege of Lucknow |

First person accounts:

- Bartrum, Katherine Mary. A Widow's Reminiscences of the Siege of Lucknow., London: James Nisbet & Co., 1858. Online at A Celebration of Women Writers.

- Inglis, Julia Selina, Lady, 1833–1904, The Siege of Lucknow: a Diary, London: James R. Osgood, McIlvaine & Co., 1892. Online at A Celebration of Women Writers.

- Rees, L. E. Ruutz. A personal narrative of the siege of Lucknow, Oxford University Press, 1858. Digital copy on Google Books.

- A Diary Kept by Mrs. R. C. Germon, at Lucknow at Project Gutenberg

Other:

- Alfred Tennyson's "The Defence of Lucknow", is poem depicting the events leading up to the day of the first relief.

External links

- Pakistan Defence Journal Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

.jpg.webp)