Siege of Arrah

The siege of Arrah (27 July – 3 August 1857) took place during the Indian Mutiny (also known as the Indian Rebellion of 1857). It was the eight-day defence of a fortified outbuilding, occupied by a combination of 18 civilians and 50 members of the Bengal Military Police Battalion, against 2,500 to 3,000 mutinying Bengal Native Infantry sepoys from three regiments and an estimated 8,000 men from irregular forces commanded by Kunwar Singh, the local zamindar or chieftain who controlled the Jagdishpur estate.

| Siege of Arrah | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 | |||||||

Defence of the Arrah House, 1857 (1858) by William Tayler | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Jagdishpur estate Mutinying Sepoys | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Kunwar Singh Babu Amar Singh Hare Krishna Singh[1] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Besieged party: 68 First relief: 400 Second relief: 225 |

Mutinying Sepoys: 2,500 – 3,000 Kunwar Singh's forces: 8,000 (Estimated) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Besieged party: 1 wounded First relief: 170 killed 120 wounded Second relief: 2 killed | Unknown | ||||||

Arrah Location of Arrah in modern-day Bihar | |||||||

An attempt to break the siege failed, with around 290 casualties out of around 415 men in the relief party. Shortly afterwards, a second relief effort consisting of 225 men and three artillery guns—carried out despite specific orders that it should not take place—dispersed the forces surrounding the building, suffering two casualties, and the besieged party escaped. Only one member of the besieged group was injured.

Background

On 10 May 1857, a mutiny by the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry, a Bengal Army unit stationed in Meerut, triggered the Indian Mutiny, which quickly spread through the Bengal Presidency.[2] The town of Arrah, headquarters of Shahabad district, besides its local inhabitants, had a population at the time that included British and European employees of the East India Company and the East Indian Railway Company, and their respective families.[3][4] In addition, there was a local police force and a jail holding between 200 and 400 inmates, with 150 armed prison guards.[5][6] The population also included many sepoys from disbanded regiments[7] and retired sepoys living on their pensions.[8] Stationed in Danapur, 25 miles (40.2 km) away, were two regiments of the British Army and three regiments of the East India Company's Bengal Native Infantry (part of the infantry component of the Bengal Army)—the 7th, 8th and 40th Regiments.[9] At the outbreak of the Indian Mutiny these were the only "native" troops in Shahabad district. They had been recruited entirely from Shahabad district and were loyal to the local zamindar (chieftain or landlord) Kunwar Singh[10] (also known as Koor,[11] Coer,[12] Koer,[10] Koowar,[13] or Kooer Sing[7]). Singh, who was around 80 years of age, had a number of grievances against the East India Company regarding deprivation of his lands and income,[14] and was described as "the high-souled chief of a warlike tribe, who had been reduced to a nonentity by the yoke of a foreign invader" by George Trevelyan in his 1864 book The Competition Wallah.[15]

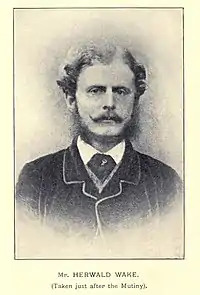

On 8 June, a letter arrived from William Tayler, the commissioner of Patna district, warning that an outbreak of mutiny from the Bengal Native Infantry units in Dinapore was to be expected.[16] The European population in Arrah spent that night at the house of Arthur Littledale, a judge working in Arrah, and during the night it was decided that the European women and children were to be sent by boat to Dinapore, escorted by armed members of the European male population, where they would be taken into the care of the 10th Regiment of Foot—this decision was acted upon on the 9th.[17] The following morning a meeting was held at the house of Herwald Wake, the magistrate of Shahabad district, to discuss what to do next.[17] The East India Company civil servants stated that they did not intend to abandon the town and they would remain.[17] All but two of the remaining European male residents of Arrah who were not civil servants or Government employees decided to leave for the relative safety of Dinapore by boat or on horseback and did so the same day.[18] This reduced the European male population of Arrah to eight,[18] rising to sixteen over the next few weeks as men arrived in the town from the surrounding district.[19] The defence of the town was augmented on 11 June when a party arrived consisting of 50 sepoys and 6 sowars from the Bengal Military Police Battalion, known as Rattray's Sikhs (now the 3rd Battalion of the Sikh Regiment, Indian Army), under the command of Jemadar Hooken Singh.[20] The party had been sent from Dinapore, part of a larger detachment under their commander Captain Rattray whose presence in the area had been personally requested by Tayler, and placed under the direct command of Wake.[21]

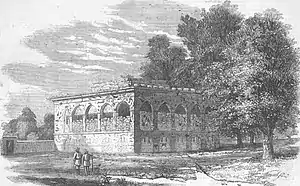

Following a suggestion from Wake, Richard Vicars Boyle, District Engineer with the East Indian Railway Company, began to fortify his two-storey, 50 by 50 ft (15 by 15 m) outbuilding (originally intended as a billiard room) and completed his work by 17 June.[21] The arches of the verandah were filled in with bricks without mortar, leaving small holes in the walls for defenders to shoot through. Gaps between pillars on the second storey were filled with bricks and sandbags. Boyle stored food, water, wine and beer in the building in anticipation of unrest in the town.[22] Although it was suggested that the civil servants should immediately move their headquarters to Boyle's building, the suggestion was dismissed due to objections to its location, the close proximity of trees, outbuildings and other houses and the possibility that abandoning their current headquarters would lead to disorder in the town.[23] Throughout June and July, news arrived in Arrah about the widespread rebellion throughout the Bengal Presidency and there were rumours that outbreaks would take place within Shahabad district imminently, leading to the decision by the civil servants to mount nightly armed patrols.[24] On 17 July, an anonymous note was found on a table in Littledale's house saying that a mutiny of sepoys was "certain to take place" on 25 July; according to the note, Kunwar Singh was directly involved.[13] News arrived in the town on 22 July concerning the massacres that had taken place during the siege of Cawnpore. Then on 25 July a letter arrived from Dinapore by express post, stating: "A revolt among the native troops is expected to occur this day. Stand prepared accordingly."[25]

Battle

The siege

Around 25 mi (40 km) east of Arrah, the 7th, 8th and 40th Regiments of Bengal Native Infantry were stationed in Dinapore, alongside the British Army's 10th and 37th Regiments of Foot. Throughout June, Tayler received anonymous letters warning him about the conduct of the sepoys, and he was informed that large sums of money were being distributed to the sepoys for unknown reasons.[26] Tayler also ordered the interception of all mail being sent to and from the three regiments,[27] leading to the discovery of plotters within Dinapore and nearby Patna who were then jailed.[28] Discussions had taken place between Tayler and his superiors about disarming the three regiments of Bengal Native Infantry stationed in Dinapore, and Governor-General Charles Canning delegated responsibility for the decision to Major General George Lloyd, military commander of the Dinapore division.[9] Instead of disarming the regiments, on the morning of 25 July Lloyd ordered the sepoys to hand in their percussion caps at 4:00 pm that day.[29] The 7th and 8th Regiments refused and fired on their officers. The 10th and 37th Regiments of Foot, also stationed in Dinapore, then opened fire on the mutineers. The 40th Regiment of Bengal Native Infantry, who had begun to comply with Lloyd's order, were also fired on in the confusion.[30] All three regiments of Bengal Native Infantry then left Dinapore heading toward Arrah. At the outbreak of the disturbance, Lloyd could not be located; by the time he was found aboard a river steamboat and orders were given to apprehend the mutineers, they were too far away to be caught. Lloyd, believing that his forces should remain in place to defend Dinapore, refused to order the pursuit of the mutineers.[31]

On the evening of 25 July, information arrived at Arrah that a disturbance was to be expected in the district. Wake had been told by a railway engineer stationed nearby that the boats used to cross the Son River would be destroyed; when Wake was informed on the morning of the 26th that the mutineers were crossing the river, he realised that the boats had in fact not been destroyed as promised.[32] Wake, who had no information about the number of mutinying sepoys and other forces approaching Arrah, noted that the local police force had disappeared and he decided not to abandon the town. Eighteen civilians and fifty members of the Bengal Military Police Battalion[33] moved into Boyle's fortified building and bricked themselves up inside.[34] The building had stores of food, drink and ammunition (with gunpowder and lead to make more if required), entrenching tools and weapons the men had brought with them. The supplies were thought to be sufficient for a few days and, since they expected the mutineers to be followed by pursuing forces, the men anticipated a brief siege of no more than 48 hours.[35] Throughout the entire siege Wake kept a diary by writing on the walls of the building so there would be a record of events if the besieged party did not survive.[36] On the morning of 27 July the mutineers, joined by Kunwar Singh and his forces, arrived in Arrah. They released the prisoners from the jail and, joined by its guards, looted the treasury of 85,000 rupees. The mutineers and rebels (including the prison guards) then surrounded the house with drums and bugles playing, arranged themselves into formation and charged. When the mutineers were within 100 yards the men inside opened fire on them, killing eighteen instantly and forcing the rest to stop their charge and take shelter behind the surrounding trees and buildings.[12]

Over the following seven days the besieged party faced constant musket fire, with fire from two artillery pieces after 28 July. When the party began to run out of water on 29 July, sepoys sneaked out of the building during the night, stole tools from their opponents and dug an 18 ft (5.5 m) well in about 12 hours.[37] When food began to run out, a small group was able to sneak out of the building on the afternoon of 30 July and return with some sheep that had been grazing within the compound.[38] Although an attempt was made to smoke the men out of the house by making a large fire of furniture and chilli peppers, a last-minute shift in wind direction blew the smoke away from the house.[39] Every evening, a voice loudly invited the Sikh sepoys in the house to slaughter the Europeans and join the mutineers, offering them 500 rupees each; it was met at first with sarcasm, and later by gunfire from the building.[40] The mutineers and rebel forces did not attempt another charge on the building, although its occupants expected an attack at any moment during the siege.[32]

First relief attempt

News reached Dinapore on 27 July that mutinying sepoys had attacked Arrah. General Lloyd was still unwilling to send troops to pursue the mutineers until he was persuaded to do so by pressure from magistrates, who were personal friends of the besieged party, and Tayler in his role as the Commissioner of Patna.[41] A party of 200 from the 37th Regiment of Foot, 50 from the Bengal Military Police Battalion and 15 loyal Sikhs from regiments that had mutinied, were sent, aboard the river steamer Horungotta,[42] to rescue the town's civil servants. News arrived in Dinapore the following day that the steamer was aground on a sandbank, and Lloyd ordered the party recalled. Under pressure from local government officials, he changed his mind and agreed to send, using the river steamer Bombay,[42] a large force of the 10th Regiment of Foot under Lieutenant Colonel William Fenwick[43] to join up with the party on the first steamer and head to Arrah. Bombay already had a large complement of civilian passengers and attempts to have the passengers removed met with confusion and arguments with the captain of the steamer, causing a delay of around four hours.[44] As a result, only a reduced force of about 150 (including seven civilian volunteers) was able to embark. Fenwick, unwilling to carry out the mission with only 150 men, delegated its command to Captain Charles Dunbar[45] (who worked in the paymaster's bureau[46]) and Bombay departed on 29 July at around 9:30 am. The two steamers met up, and the combined force of about 415 then headed towards Arrah.[47]

The expedition arrived at a place called Beharee Ghat on the western bank of the Son River and disembarked at about 4:00 pm.[48] Their path was then blocked by a large stream that could only be crossed using boats.[48] The party took three hours to cross the stream and head inland. After the expedition had marched 4 mi (6.4 km), Dunbar halted them 3 mi (4.8 km) from Arrah for one hour to see if his supplies would catch up to him. When the supplies did not arrive, he ordered the expedition to press on, despite warnings from his subordinate officers of the danger of hungry, tired men marching through unfamiliar territory at night.[46] Up to this point in the expedition, Dunbar had sent skirmishers as scouts ahead of his main body of troops; he now decided not to do so and the men advanced in a single body.[46] As the party neared Arrah, they spotted men on horseback, whom they took to be vedettes (mounted sentries), that rode away as they approached. When the expedition was about 1 mi (1.6 km) from Arrah, its route passed through a thick grove of mango trees. As the expedition was almost through the grove, they were fired on from three sides by a force they estimated as 2,000 to 3,000 in number.[49] Heavy casualties were suffered during the initial ambush, including Dunbar (who was killed instantly), and the force broke up in confusion. The besieged party in Arrah heard the sound of gunfire, growing louder as the expedition approached them, then becoming more distant as the expedition retreated, and they immediately inferred that something must have gone wrong.[48] A wounded member of the Bengal Military Police Battalion who was part of Dunbar's force was able to avoid the mutinying sepoys surrounding Boyle's building. Pulled up into the building with a rope, he told its occupants about the ambush.[50]

During the retreat from Arrah, Ross Mangles and William Fraser McDonell (civilian magistrates, and personal friends of Wake, who had volunteered to serve with Dunbar's expedition) earned the Victoria Cross—Mangles, despite being wounded, carried a wounded soldier from the 37th Regiment of Foot for several miles while under fire,[51] and McDonnell exposed himself to heavy fire to cut a rope that was preventing a boat from making its escape, saving the lives of 35 soldiers.[52] The steamer carrying the expedition returned to Dinapore on 30 July, and families and friends were waiting at the dock expecting to welcome home the victorious men. When the steamer docked outside the hospital instead of at its usual berth, the spectators realised something was wrong. In the words of Tayler: "The scene that ensued was heart-rending, the soldiers' wives rushed down, screaming, to the edge of the water, beating their breasts and tearing their hair, despondency and despair were depicted on every countenance."[53] Out of 415 men, the expedition had suffered 170 fatalities and 120 wounded.[48]

Second attempt

Major Vincent Eyre, a Bengal Artillery officer in command of the East India Company's Number 1 Company, 4th Bengal Foot Artillery—now 58 (Eyre's) Battery, 12th Regiment Royal Artillery, British Army—then stationed in Buxar, was under orders to head to Cawnpore with his battery. He had heard news of the situation in Arrah and, unaware of any relief expedition, decided on his own to collect troops to reinforce the expedition he believed would take place. Finding no troops available at Buxar, Eyre went to Ghazipur and was able to attach 25 men from the 78th (Highlanders) Regiment of Foot to his party. Upon returning to Buxar, Eyre found that 154 men from the 5th Regiment of Foot had arrived in his absence and he convinced their commander, Captain L'Estrange, to join him with the understanding that Eyre bore full responsibility. At this point, Eyre felt so confident of victory that he dismissed the men from the 78th Foot and went ahead without them.[54] Unable to locate horses to move his battery's guns, Eyre used bullocks (neutered bulls) instead and was able to procure two elephants to move the party's baggage.[55] After assembling a force of 225 men (including civilian volunteers) and three of his battery's guns, Eyre wrote to General Lloyd at Dinapore informing him of his intentions and requesting reinforcements. On 30 July, at about 4:00 pm, Eyre's expedition started for Arrah.[56]

Lloyd's reply, informing Eyre of the failure of the first relief attempt and ordering him not to commence his mission, or to return to Buxar to await further orders if he had already started, arrived while the party was en route. Eyre disregarded Lloyd's order and continued towards Arrah.[57] On 2 August, still over 6 mi (9.7 km) from his objective, Eyre's force encountered an estimated 2,000 to 2,500 mutinying sepoys accompanied by Kunwar Singh's forces—including Kunwar Singh himself—headed to intercept him.[32] Greatly outnumbered, Eyre's party became surrounded. He then ordered the infantry to charge with bayonets and the artillery to fire on the mutineers. This caused the mutinying sepoys to retreat, with an estimated 600 casualties.[58] Eyre's party, with only two killed,[32] then continued towards Arrah. Blocked by a river, they built a bridge which they completed the following day. When they crossed the river on the morning of 3 August, a villager gave them a letter from Wake telling them that the besieged men had heard about their approach, stating "We are all well."[58]

Throughout the day of 2 August the besieged party heard distant cannon fire and saw people in the town hurriedly loading carts with their belongings.[59] The constant fire from muskets on the building lessened and finally ceased; it was approached by two men, who told the occupants that the besiegers were defeated and a relief force was expected to arrive in Arrah the following day.[60] The occupants were sceptical, despite visual evidence, and sent out a small party at midnight to reconnoitre the area—they found no sign of the mutineers and brought in a large quantity of gunpowder and the mutineers' two artillery pieces. They then sent a party under cover of darkness to destroy a number of outhouses which the mutineers had been using as cover. This party discovered a mine dug directly under the foundations of the building by the mutineers, charged and ready to be primed, so this charge was destroyed by them. The following morning at about 7:00 am, two members of Major Eyre's expedition arrived at the house and the siege was officially broken.[61] Eyre, in his official report, wrote that Wake's defence of the building "seems to have been almost miraculous." About the outcome of the first relief attempt, he wrote: "I venture to affirm, confidently, that no such disaster would have been likely to occur, had that detachment advanced less precipitately, so as to have given full time for my force to approach direct from the opposite side, for the rebels would then have been hemmed in between the two opposing forces, and must have been utterly routed."[32]

According to Wake's official report about the siege, "Nothing but cowardice, want of unanimity, and only the ignorance of our enemies, prevented our fortification being brought down about our ears."[32] In his own report, Tayler wrote, "The conduct of the garrison is most creditable, and the gallantry and fidelity of the Sikhs beyond all praise."[32]

Awards

For their actions during the siege, Wake was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath,[62] and Boyle was made a Companion of the Order of the Star of India after the 1861 creation of the order.[63] A few days after the relief of Arrah, the 50 besieged members of the Bengal Military Police Battalion received a gratuity of 12 months' pay as a reward for their loyalty and Jemadar Singh was promoted to Subedar upon Wake's recommendation.[32] For its actions in Arrah the Bengal Military Police Battalion received the Defence of Arrah (1857) battle honour and was also given the Bihar (1857) battle honour for its role in safeguarding the area. These battle honours are unique to the Bengal Military Police Battalion as they were awarded to no other unit.[64] Major Eyre was recommended for the Victoria Cross by Sir James Outram, Commissioner of Oude and the overall military commander for the region, for his conduct in Arrah, but this was not awarded.[65]

Aftermath

Eyre, after receiving reinforcements, pursued Kunwar Singh's forces to Singh's palace in Jagdispur.[48] Many civilians who were besieged in Arrah, including Wake (still commanding the 50 men of the Bengal Military Police Battalion), volunteered to serve with him. Although Singh's forces were routed and the palace occupied by 12 August, Singh had fled. Eyre's force destroyed most of the town of Jagdispur including the palace (in the nearby jungle), Singh's brothers' houses and a Brahmin temple.[48] Eyre was publicly censured by Governor General Canning in The London Gazette for the temple's destruction.[66] The Siege of Arrah marked the beginning of Singh's fight against the East India Company. Following Arrah he fought on, first leading his irregular forces to Lucknow, then keeping them together during an organised retreat back to Jagdispur. Singh died in April 1858. His irregular forces continued to fight, repelling an expedition sent to destroy them, until they finally laid down their arms in November 1858 as part of the general amnesty.[67] Following the general amnesty, unrest continued, and peace was not officially declared until 8 July 1859.[68]

The besieged building still stands on the grounds of Maharaja College, Arrah, where it now houses a museum commemorating the life of Kunwar Singh, although according to Abhay Kumar of the Deccan Herald, as of May 2015 it "hardly has any item related to Kunwar Singh."[69]

Legacy

After visiting the site in 1864, Trevelyan wrote:

Already the wall, on which Wake wrote the diary of the siege, has been whitewashed... a party-wall has been built over the mouth of the well in the cellars; and the garden-fence, which served the mutineers as a first parallel, has been moved twenty yards back. Half a century more, and every vestige of the struggle may have been swept away. But, as long as Englishmen love to hear of fidelity, and constancy, and courage bearing up the day against frightful odds, there is no fear lest they forget the name of "the little house at Arrah."[70]

References

Citations

- Kalikinkar Datta (1957). Biography of Kunwar Singh and Amar Singh. K.P. Jayaswal Research Institute. p. 29.

- Dodd 1859, pp. 48–58.

- Sieveking 1910, pp. 18–19.

- Halls 1860, p. 9.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 18.

- Halls 1860, pp. 9–10.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 43.

- Trevelyan 1864, p. 92.

- Dodd 1859, p. 267.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 19.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 150.

- Trevelyan 1864, p. 89.

- Halls 1860, p. 33.

- Sieveking 1910, pp. 19–20.

- Trevelyan 1864, p. 90.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 21.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 22.

- Halls 1860, p. 14.

- Boyle 1858, p. 7.

- Halls 1860, p. 67.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 25.

- Boyle 1858, p. 8.

- Halls 1860, p. 26.

- Halls 1860, pp. 28–31.

- Halls 1860, p. 34.

- Tayler 1858, pp. 30–40.

- Trevelyan 1864, p. 72.

- Tayler 1858, pp. 39–40.

- Trevelyan 1864, p. 84.

- Forrest 2006, p. 417.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 50.

- "No. 22050". The London Gazette. 13 October 1857. pp. 3418–3422.

- O'Malley 1906, p. 128.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 28.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 46.

- Sieveking 1910, pp. 41–45.

- Forrest 2006, p. 438.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 44.

- Sieveking 1910, pp. 30–31.

- Trevelyan 1864, p. 93.

- Tayler 1858, p. 78.

- Dodd 1859, p. 270.

- "No. 21714". The London Gazette. 18 May 1855. p. 1918.

- Tayler 1858, pp. 79–81.

- Best 2016, Patna.

- Trevelyan 1864, p. 94.

- Sieveking 1910, pp. 51–53.

- Dodd 1859, p. 271.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 58.

- Halls 1860, pp. 46–48.

- "No. 22283". The London Gazette. 8 July 1859. p. 2629.

- "No. 22357". The London Gazette. 17 February 1860. p. 557.

- Tayler 1858, p. 83.

- Forrest 2006, p. 448.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 83.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 81.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 74.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 90.

- Trevelyan 1864, p. 109.

- Halls 1860, pp. 52–53.

- Halls 1860, p. 54.

- "No. 22387". The London Gazette. 18 May 1860. p. 1916.

- "Boyle of Arrah". The Montreal Gazette. 21 January 1908. p. 9. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- Singh 1993, p. 10.

- Sieveking 1910, p. 80.

- "No. 22069". The London Gazette. 4 December 1857. p. 4264.

- Trevelyan 1864, pp. 91–92.

- Prichard 1869, p. 43.

- Kumar, Abhay (31 May 2015). "CJ's chance visit helps breathe life into Ara House". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- Trevelyan 1864, p. 111.

Sources

- Best, Brian (2016). The Victoria Crosses that Saved an Empire: The Story of the VCs of the Indian Mutiny. Barnsley: Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-4738-5707-0.

- Boyle, Richard Vicars (1858). Indian Mutiny, Brief Narrative of the Defence of the Arrah Garrison. London: W. Thacker & Co. OCLC 794643208.

- Dodd, George (1859). The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China, and Japan, 1856–7–8: With Maps, Plans, and Wood Engravings. London: W. and R. Chambers. OCLC 248904480.

- Forrest, George (2006). A History of the Indian Mutiny, 1857–58 (Volume III). London (1904 original), New Delhi (2006 reprint): Gautam Jetley (reprint). ISBN 81-206-1999-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Halls, John James (1860). Two Months in Arrah in 1857. London: Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts. OCLC 877907.

- O'Malley, Lewis Sydney Steward (1906). Shahabad. Calcutta: The Bengal Secretariat Book Depot. OCLC 252001000.

- Prichard, Iltudus Thomas (1869). The administration of India from 1859 to 1868: the first ten years of administration under the Crown. London: MacMillan & Company. OCLC 908361033.

- Sieveking, Isabel Giberne (1910). A Turning Point in the Indian Mutiny. London: D. Nutt. OCLC 13203015.

- Singh, Sarbans (1993). Battle Honours of the Indian Army 1757 – 1971. New Delhi: Vision Books. ISBN 81-7094-115-6.

- Tayler, William (1858). The Patna Crisis; Or, Three Months at Patna, During the Insurrection of 1857. London: J. Nisbet. OCLC 748092097.

- Trevelyan, George Otto (1864). The Competition Wallah. London: MacMillan & Company. OCLC 308875870.