MHC class I

MHC class I molecules are one of two primary classes of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules (the other being MHC class II) and are found on the cell surface of all nucleated cells in the bodies of vertebrates.[1][2] They also occur on platelets, but not on red blood cells. Their function is to display peptide fragments of proteins from within the cell to cytotoxic T cells; this will trigger an immediate response from the immune system against a particular non-self antigen displayed with the help of an MHC class I protein. Because MHC class I molecules present peptides derived from cytosolic proteins, the pathway of MHC class I presentation is often called cytosolic or endogenous pathway.[3]

| MHC class I | |

|---|---|

Schematic representation of MHC class I | |

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | MHC class I |

| Membranome | 63 |

In humans, the HLAs corresponding to MHC class I are HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C.

Function

Class I MHC molecules bind peptides generated mainly from degradation of cytosolic proteins by the proteasome. The MHC I:peptide complex is then inserted via endoplasmic reticulum into the external plasma membrane of the cell. The epitope peptide is bound on extracellular parts of the class I MHC molecule. Thus, the function of the class I MHC is to display intracellular proteins to cytotoxic T cells (CTLs). However, class I MHC can also present peptides generated from exogenous proteins, in a process known as cross-presentation.

A normal cell will display peptides from normal cellular protein turnover on its class I MHC, and CTLs will not be activated in response to them due to central and peripheral tolerance mechanisms. When a cell expresses foreign proteins, such as after viral infection, a fraction of the class I MHC will display these peptides on the cell surface. Consequently, CTLs specific for the MHC:peptide complex will recognize and kill presenting cells.

Alternatively, class I MHC itself can serve as an inhibitory ligand for natural killer cells (NKs). Reduction in the normal levels of surface class I MHC, a mechanism employed by some viruses[4] and certain tumors to evade CTL responses, activates NK cell killing.

PirB and visual plasticity

Paired-immunoglobulin-like receptor B (PirB), an MHCI-binding receptor, is involved in the regulation of visual plasticity.[5] PirB is expressed in the central nervous system and diminishes ocular dominance plasticity in the developmental critical period and adulthood.[5] When the function of PirB was abolished in mutant mice, ocular dominance plasticity became more pronounced at all ages.[5] PirB loss of function mutant mice also exhibited enhanced plasticity after monocular deprivation during the critical period.[5] These results suggest PirB may be involved in modulation of synaptic plasticity in the visual cortex.

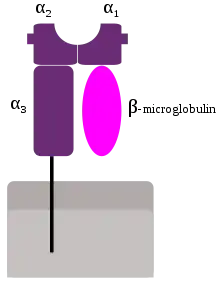

Structure

MHC class I molecules are heterodimers that consist of two polypeptide chains, α and β2-microglobulin (B2M). The two chains are linked noncovalently via interaction of B2M and the α3 domain. Only the α chain is polymorphic and encoded by a HLA gene, while the B2M subunit is not polymorphic and encoded by the Beta-2 microglobulin gene. The α3 domain is plasma membrane-spanning and interacts with the CD8 co-receptor of T-cells. The α3-CD8 interaction holds the MHC I molecule in place while the T cell receptor (TCR) on the surface of the cytotoxic T cell binds its α1-α2 heterodimer ligand, and checks the coupled peptide for antigenicity. The α1 and α2 domains fold to make up a groove for peptides to bind. MHC class I molecules bind peptides that are predominantly 8-10 amino acid in length (Parham 87), but the binding of longer peptides have also been reported.[6]

While a high-affinity peptide and the B2M subunit are normally required to maintain a stable ternary complex between the peptide, MHC I, and B2M, under subphysiological temperatures, stable, peptide-deficient MHC I/B2M heterodimers have been observed.[7][8] Synthetic stable, peptide-receptive MHC I molecules have been generated using a disulfide bond between the MHC I and B2M, named "open MHC-I".[9]

Synthesis

The peptides are generated mainly in the cytosol by the proteasome. The proteasome is a macromolecule that consists of 28 subunits, of which half affect proteolytic activity. The proteasome degrades intracellular proteins into small peptides that are then released into the cytosol. Proteasomes can also ligate distinct peptide fragments (termed spliced peptides), producing sequences that are noncontiguous and therefore not linearly templated in the genome. The origin of spliced peptide segments can be from the same protein (cis-splicing) or different proteins (trans-splicing).[10][11] The peptides have to be translocated from the cytosol into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to meet the MHC class I molecule, whose peptide-binding site is in the lumen of the ER. They have membrane proximal Ig fold

Translocation and peptide loading

The peptide translocation from the cytosol into the lumen of the ER is accomplished by the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP). TAP is a member of the ABC transporter family and is a heterodimeric multimembrane-spanning polypeptide consisting of TAP1 and TAP2. The two subunits form a peptide binding site and two ATP binding sites that face the cytosol. TAP binds peptides on the cytoplasmic side and translocates them under ATP consumption into the lumen of the ER. The MHC class I molecule is then, in turn, loaded with peptides in the lumen of the ER.

The peptide-loading process involves several other molecules that form a large multimeric complex called the Peptide loading complex[12] consisting of TAP, tapasin, calreticulin, calnexin, and Erp57 (PDIA3). Calnexin acts to stabilize the class I MHC α chains prior to β2m binding. Following complete assembly of the MHC molecule, calnexin dissociates. The MHC molecule lacking a bound peptide is inherently unstable and requires the binding of the chaperones calreticulin and Erp57. Additionally, tapasin binds to the MHC molecule and serves to link it to the TAP proteins and facilitates the selection of peptide in an iterative process called peptide editing,[13][14][15] thus facilitating enhanced peptide loading and colocalization.

Once the peptide is loaded onto the MHC class I molecule, the complex dissociates and it leaves the ER through the secretory pathway to reach the cell surface. The transport of the MHC class I molecules through the secretory pathway involves several posttranslational modifications of the MHC molecule. Some of the posttranslational modifications occur in the ER and involve change to the N-glycan regions of the protein, followed by extensive changes to the N-glycans in the Golgi apparatus. The N-glycans mature fully before they reach the cell surface.

Peptide removal

Peptides that fail to bind MHC class I molecules in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) are removed from the ER via the sec61 channel into the cytosol,[16][17] where they might undergo further trimming in size, and might be translocated by TAP back into ER for binding to a MHC class I molecule.

For example, an interaction of sec61 with bovine albumin has been observed.[18]

Effect of viruses

MHC class I molecules are loaded with peptides generated from the degradation of ubiquitinated cytosolic proteins in proteasomes. As viruses induce cellular expression of viral proteins, some of these products are tagged for degradation, with the resulting peptide fragments entering the endoplasmic reticulum and binding to MHC I molecules. It is in this way, the MHC class I-dependent pathway of antigen presentation, that the virus infected cells signal T-cells that abnormal proteins are being produced as a result of infection.

The fate of the virus-infected cell is almost always induction of apoptosis through cell-mediated immunity, reducing the risk of infecting neighboring cells. As an evolutionary response to this method of immune surveillance, many viruses are able to down-regulate or otherwise prevent the presentation of MHC class I molecules on the cell surface. In contrast to cytotoxic T lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells are normally inactivated upon recognizing MHC I molecules on the surface of cells. Therefore, in the absence of MHC I molecules, NK cells are activated and recognize the cell as aberrant, suggesting that it may be infected by viruses attempting to evade immune destruction. Several human cancers also show down-regulation of MHC I, giving transformed cells the same survival advantage of being able to avoid normal immune surveillance designed to destroy any infected or transformed cells.[19]

Genes and isotypes

Evolutionary history

The MHC class I genes originated in the most recent common ancestor of all jawed vertebrates, and have been found in all living jawed vertebrates that have been studied thus far.[2] Since their emergence in jawed vertebrates, this gene family has been subjected to many divergent evolutionary paths as speciation events have taken place. There are, however, documented cases of trans-species polymorphisms in MHC class I genes, where a particular allele in an evolutionary related MHC class I gene remains in two species, likely due to strong pathogen-mediated balancing selection by pathogens that can infect both species.[20] Birth-and-death evolution is one of the mechanistic explanations for the size of the MHC class I gene family.

Birth-and-death of MHC class I genes

Birth-and-death evolution asserts that gene duplication events cause the genome to contain multiple copies of a gene which can then undergo separate evolutionary processes. Sometimes these processes result in pseudogenization (death) of one copy of the gene, though sometimes this process results in two new genes with divergent function.[21] It is likely that human MHC class Ib loci (HLA-E, -F, and -G) as well as MHC class I pseudogenes arose from MHC class Ia loci (HLA-A, -B, and -C) in this birth-and-death process.[22]

References

- Hewitt EW (October 2003). "The MHC class I antigen presentation pathway: strategies for viral immune evasion". Immunology. 110 (2): 163–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01738.x. PMC 1783040. PMID 14511229.

- Kulski JK, Shiina T, Anzai T, Kohara S, Inoko H (December 2002). "Comparative genomic analysis of the MHC: the evolution of class I duplication blocks, diversity and complexity from shark to man". Immunological Reviews. 190: 95–122. doi:10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.19008.x. PMID 12493009. S2CID 41765680.

- http://users.rcn.com/jkimball.ma.ultranet/BiologyPages/H/HLA.html#Class_I_Histocompatibility_Molecules Kimball's Biology Pages, Histocompatibility Molecules

- Hansen TH, Bouvier M (July 2009). "MHC class I antigen presentation: learning from viral evasion strategies". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 9 (7): 503–13. doi:10.1038/nri2575. PMID 19498380. S2CID 9278263.

- Syken J, Grandpre T, Kanold PO, Shatz CJ (September 2006). "PirB restricts ocular-dominance plasticity in visual cortex". Science. 313 (5794): 1795–800. Bibcode:2006Sci...313.1795S. doi:10.1126/science.1128232. PMID 16917027. S2CID 1860730.

- Burrows SR, Rossjohn J, McCluskey J (January 2006). "Have we cut ourselves too short in mapping CTL epitopes?". Trends in Immunology. 27 (1): 11–6. doi:10.1016/j.it.2005.11.001. PMID 16297661.

- Ljunggren, Hans-Gustaf; Stam, Nico J.; Öhlén, Claes; Neefjes, Jacques J.; Höglund, Petter; Heemels, Marie-Thérèse; Bastin, Judy; Schumacher, Ton N. M.; Townsend, Alain; Kärre, Klas; Ploegh, Hidde L. (1990-08-02). "Empty MHC class I molecules come out in the cold". Nature. 346 (6283): 476–480. doi:10.1038/346476a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- Schumacher, Ton N.M.; Heemels, Marie-Thérèse; Neefjes, Jacques J.; Kast, W.Martin; Melief, Cees J.M.; Ploegh, Hidde L. (August 1990). "Direct binding of peptide to empty MHC class I molecules on intact cells and in vitro". Cell. 62 (3): 563–567. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90020-F.

- Sun, Yi; Young, Michael C.; Woodward, Claire H.; Danon, Julia N.; Truong, Hau V.; Gupta, Sagar; Winters, Trenton J.; Font-Burgada, Joan; Burslem, George M.; Sgourakis, Nikolaos G. (2023-06-20). "Universal open MHC-I molecules for rapid peptide loading and enhanced complex stability across HLA allotypes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 120 (25). doi:10.1073/pnas.2304055120. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 10288639.

- Faridi, Pouya; Li, Chen; Ramarathinam, Sri H.; Vivian, Julian P.; Illing, Patricia T.; Mifsud, Nicole A.; Ayala, Rochelle; Song, Jiangning; Gearing, Linden J.; Hertzog, Paul J.; Ternette, Nicola; Rossjohn, Jamie; Croft, Nathan P.; Purcell, Anthony W. (12 October 2018). "A subset of HLA-I peptides are not genomically templated: Evidence for cis- and trans-spliced peptide ligands" (PDF). Science Immunology. 3 (28): eaar3947. doi:10.1126/sciimmunol.aar3947. PMID 30315122.

- Liepe, Juliane; Marino, Fabio; Sidney, John; Jeko, Anita; Bunting, Daniel E.; Sette, Alessandro; Kloetzel, Peter M.; Stumpf, Michael P. H.; Heck, Albert J. R.; Mishto, Michele (21 October 2016). "A large fraction of HLA class I ligands are proteasome-generated spliced peptides" (PDF). Science. 354 (6310): 354–358. Bibcode:2016Sci...354..354L. doi:10.1126/science.aaf4384. hdl:10044/1/42330. PMID 27846572. S2CID 41095551.

- Blees A, Januliene D, Hofmann T, Koller N, Schmidt C, Trowitzsch S, Moeller A, Tampé R (November 2017). "Structure of the human MHC-I peptide-loading complex". Nature. 551 (7681): 525–528. Bibcode:2017Natur.551..525B. doi:10.1038/nature24627. PMID 29107940. S2CID 4447406.

- Howarth M, Williams A, Tolstrup AB, Elliott T (August 2004). "Tapasin enhances MHC class I peptide presentation according to peptide half-life". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (32): 11737–42. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10111737H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0306294101. PMC 511045. PMID 15286279.

- Wearsch PA, Cresswell P (August 2007). "Selective loading of high-affinity peptides onto major histocompatibility complex class I molecules by the tapasin-ERp57 heterodimer". Nature Immunology. 8 (8): 873–81. doi:10.1038/ni1485. PMID 17603487. S2CID 29762957.

- Thirdborough SM, Roddick JS, Radcliffe JN, Howarth M, Stevenson FK, Elliott T (February 2008). "Tapasin shapes immunodominance hierarchies according to the kinetic stability of peptide-MHC class I complexes". European Journal of Immunology. 38 (2): 364–9. doi:10.1002/eji.200737832. PMID 18196518. S2CID 28659293.

- Koopmann JO, Albring J, Hüter E, Bulbuc N, Spee P, Neefjes J, Hämmerling GJ, Momburg F, et al. (July 2000). "Export of antigenic peptides from the endoplasmic reticulum intersects with retrograde protein translocation through the Sec61p channel". Immunity. 13 (1): 117–27. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(00)00013-3. PMID 10933400.

- Albring J, Koopmann JO, Hämmerling GJ, Momburg F (January 2004). "Retrotranslocation of MHC class I heavy chain from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol is dependent on ATP supply to the ER lumen". Molecular Immunology. 40 (10): 733–41. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2003.08.008. PMID 14644099.

- Imai J, Hasegawa H, Maruya M, Koyasu S, Yahara I (January 2005). "Exogenous antigens are processed through the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) in cross-presentation by dendritic cells". International Immunology. 17 (1): 45–53. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxh184. PMID 15546887.

- Wang Z, Zhang L, Qiao A, Watson K, Zhang J, Fan GH (February 2008). "Activation of CXCR4 triggers ubiquitination and down-regulation of major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) on epithelioid carcinoma HeLa cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283 (7): 3951–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.m706848200. PMID 18083706.

- Azevedo L, Serrano C, Amorim A, Cooper DN (September 2015). "Trans-species polymorphism in humans and the great apes is generally maintained by balancing selection that modulates the host immune response". Human Genomics. 9 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/s40246-015-0043-1. PMC 4559023. PMID 26337052.

- Nei M, Rooney AP (2005-11-14). "Concerted and birth-and-death evolution of multigene families". Annual Review of Genetics. 39 (1): 121–52. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.112240. PMC 1464479. PMID 16285855.

- Hughes AL (March 1995). "Origin and evolution of HLA class I pseudogenes". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 12 (2): 247–58. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040201. PMID 7700152.

External links

- Histocompatibility+Antigens+Class+I at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- MHC+Class+I+Genes at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)