Magnetocrystalline anisotropy

In physics, a ferromagnetic material is said to have magnetocrystalline anisotropy if it takes more energy to magnetize it in certain directions than in others. These directions are usually related to the principal axes of its crystal lattice. It is a special case of magnetic anisotropy. In other words, the excess energy required to magnetize a specimen in a particular direction over that required to magnetize it along the easy direction is called crystalline anisotropy energy.

Causes

The spin-orbit interaction is the primary source of magnetocrystalline anisotropy. It is basically the orbital motion of the electrons which couples with crystal electric field giving rise to the first order contribution to magnetocrystalline anisotropy. The second order arises due to the mutual interaction of the magnetic dipoles. This effect is weak compared to the exchange interaction and is difficult to compute from first principles, although some successful computations have been made.[1]

Practical relevance

Magnetocrystalline anisotropy has a great influence on industrial uses of ferromagnetic materials. Materials with high magnetic anisotropy usually have high coercivity, that is, they are hard to demagnetize. These are called "hard" ferromagnetic materials and are used to make permanent magnets. For example, the high anisotropy of rare-earth metals is mainly responsible for the strength of rare-earth magnets. During manufacture of magnets, a powerful magnetic field aligns the microcrystalline grains of the metal such that their "easy" axes of magnetization all point in the same direction, freezing a strong magnetic field into the material.

On the other hand, materials with low magnetic anisotropy usually have low coercivity, their magnetization is easy to change. These are called "soft" ferromagnets and are used to make magnetic cores for transformers and inductors. The small energy required to turn the direction of magnetization minimizes core losses, energy dissipated in the transformer core when the alternating current changes direction.

Thermodynamic theory

The magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy is generally represented as an expansion in powers of the direction cosines of the magnetization. The magnetization vector can be written M = Ms(α,β,γ), where Ms is the saturation magnetization. Because of time reversal symmetry, only even powers of the cosines are allowed.[2] The nonzero terms in the expansion depend on the crystal system (e.g., cubic or hexagonal).[2] The order of a term in the expansion is the sum of all the exponents of magnetization components, e.g., α β is second order.

Uniaxial anisotropy

More than one kind of crystal system has a single axis of high symmetry (threefold, fourfold or sixfold). The anisotropy of such crystals is called uniaxial anisotropy. If the z axis is taken to be the main symmetry axis of the crystal, the lowest order term in the energy is[5]

The ratio E/V is an energy density (energy per unit volume). This can also be represented in spherical polar coordinates with α = cos sin θ, β = sin sin θ, and γ = cos θ:

The parameter K1, often represented as Ku, has units of energy density and depends on composition and temperature.

The minima in this energy with respect to θ satisfy

If K1 > 0, the directions of lowest energy are the ± z directions. The z axis is called the easy axis. If K1 < 0, there is an easy plane perpendicular to the symmetry axis (the basal plane of the crystal).

Many models of magnetization represent the anisotropy as uniaxial and ignore higher order terms. However, if K1 < 0, the lowest energy term does not determine the direction of the easy axes within the basal plane. For this, higher-order terms are needed, and these depend on the crystal system (hexagonal, tetragonal or rhombohedral).[2]

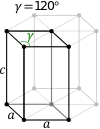

The hexagonal lattice cell.

The hexagonal lattice cell. The tetragonal lattice cell.

The tetragonal lattice cell. The rhombohedral lattice cell.

The rhombohedral lattice cell.

Hexagonal system

In a hexagonal system the c axis is an axis of sixfold rotation symmetry. The energy density is, to fourth order,[7]

The uniaxial anisotropy is mainly determined by these first two terms. Depending on the values K1 and K2, there are four different kinds of anisotropy (isotropic, easy axis, easy plane and easy cone):[7]

- K1 = K2 = 0: the ferromagnet is isotropic.

- K1 > 0 and K2 > −K1: the c axis is an easy axis.

- K1 > 0 and K2 < −K1: the basal plane is an easy plane.

- K1 < 0 and K2 < −K1/2: the basal plane is an easy plane.

- −2K2 < K1 < 0: the ferromagnet has an easy cone (see figure to right).

The basal plane anisotropy is determined by the third term, which is sixth-order. The easy directions are projected onto three axes in the basal plane.

Below are some room-temperature anisotropy constants for hexagonal ferromagnets. Since all the values of K1 and K2 are positive, these materials have an easy axis.

| Structure | ||

|---|---|---|

| Co | 45 | 15 |

| αFe2O3 (hematite) | 120[9] | |

| BaO · 6Fe2O3 | 3 | |

| YCo5 | 550 | |

| MnBi | 89 | 27 |

Higher order constants, in particular conditions, may lead to first order magnetization processes FOMP.

Tetragonal and rhombohedral systems

The energy density for a tetragonal crystal is[2]

- .

Note that the K3 term, the one that determines the basal plane anisotropy, is fourth order (same as the K2 term). The definition of K3 may vary by a constant multiple between publications.

The energy density for a rhombohedral crystal is[2]

- .

Cubic anisotropy

In a cubic crystal the lowest order terms in the energy are[10][2]

If the second term can be neglected, the easy axes are the ⟨100⟩ axes (i.e., the ± x, ± y, and ± z, directions) for K1 > 0 and the ⟨111⟩ directions for K1 < 0 (see images on right).

If K2 is not assumed to be zero, the easy axes depend on both K1 and K2. These are given in the table below, along with hard axes (directions of greatest energy) and intermediate axes (saddle points) in the energy). In energy surfaces like those on the right, the easy axes are analogous to valleys, the hard axes to peaks and the intermediate axes to mountain passes.

| Type of axis | to | to | to |

|---|---|---|---|

| Easy | ⟨100⟩ | ⟨100⟩ | ⟨111⟩ |

| Medium | ⟨110⟩ | ⟨111⟩ | ⟨100⟩ |

| Hard | ⟨111⟩ | ⟨110⟩ | ⟨110⟩ |

| Type of axis | to | to | to |

|---|---|---|---|

| Easy | ⟨111⟩ | ⟨110⟩ | ⟨110⟩ |

| Medium | ⟨110⟩ | ⟨111⟩ | ⟨100⟩ |

| Hard | ⟨100⟩ | ⟨100⟩ | ⟨111⟩ |

Below are some room-temperature anisotropy constants for cubic ferromagnets. The compounds involving Fe2O3 are ferrites, an important class of ferromagnets. In general the anisotropy parameters for cubic ferromagnets are higher than those for uniaxial ferromagnets. This is consistent with the fact that the lowest order term in the expression for cubic anisotropy is fourth order, while that for uniaxial anisotropy is second order.

| Structure | ||

|---|---|---|

| Fe | 4.8 | ±0.5 |

| Ni | −0.5 | (-0.5)–(-0.2)[14][15] |

| FeO· Fe2O3 (magnetite) | −1.1 | |

| MnO· Fe2O3 | −0.3 | |

| NiO· Fe2O3 | −0.62 | |

| MgO· Fe2O3 | −0.25 | |

| CoO· Fe2O3 | 20 | |

Temperature dependence of anisotropy

The magnetocrystalline anisotropy parameters have a strong dependence on temperature. They generally decrease rapidly as the temperature approaches the Curie temperature, so the crystal becomes effectively isotropic.[11] Some materials also have an isotropic point at which K1 = 0. Magnetite (Fe3O4), a mineral of great importance to rock magnetism and paleomagnetism, has an isotropic point at 130 kelvin.[9]

Magnetite also has a phase transition at which the crystal symmetry changes from cubic (above) to monoclinic or possibly triclinic below. The temperature at which this occurs, called the Verwey temperature, is 120 Kelvin.[9]

Magnetostriction

The magnetocrystalline anisotropy parameters are generally defined for ferromagnets that are constrained to remain undeformed as the direction of magnetization changes. However, coupling between the magnetization and the lattice does result in deformation, an effect called magnetostriction. To keep the lattice from deforming, a stress must be applied. If the crystal is not under stress, magnetostriction alters the effective magnetocrystalline anisotropy. If a ferromagnet is single domain (uniformly magnetized), the effect is to change the magnetocrystalline anisotropy parameters.[16]

In practice, the correction is generally not large. In hexagonal crystals, there is no change in K1.[17] In cubic crystals, there is a small change, as in the table below.

| Structure | ||

|---|---|---|

| Fe | 4.7 | 4.7 |

| Ni | −0.60 | −0.59 |

| FeO·Fe2O3 (magnetite) | −1.10 | −1.36 |

See also

Notes and references

- Daalderop, Kelly & Schuurmans 1990

- Landau, Lifshitz & Pitaevski 2004

- Atzmony, U.; Dariel, M. P. (1976). "Nonmajor cubic symmetry axes of easy magnetization in rare-earth-iron Laves compounds". Phys. Rev. B. 13. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.13.4006.

- Cullity, Bernard Dennis (1972). Introduction to Magnetic Materials. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. p. 214.

- An arbitrary constant term is ignored.

- The lowest-order term in the energy can be written in more than one way because, by definition, α2+β2+γ2 = 1.

- Cullity & Graham 2008, pp. 202–203

- Cullity & Graham 2008, p. 227

- Dunlop & Özdemir 1997

- Cullity & Graham 2008, p. 201

- Cullity & Graham 2008

- Samad, Fabian; Hellwig, Olav (2023). "Determining the preferred directions of magnetisation in cubic crystals using symmetric polynomial inequalities". Emergent Scientist. 7. doi:10.1051/emsci/2023002.

- Krause, D. (1964). "Über die magnetische Anisotropieenergie kubischer Kristalle". Phys. Status Solidi B. 6. doi:10.1002/pssb.19640060110.

- Lord, D. G.; Goddard, J. (1970). "Magnetic Anisotropy in F.C.C. Single Crystal Cobalt—Nickel Electrodeposited Films. I. Magnetocrystalline Anisotropy Constants from (110) and (001) Deposits". Physica Status Solidi B. 37 (2): 657–664. Bibcode:1970PSSBR..37..657L. doi:10.1002/pssb.19700370216.

- Early measurements for nickel were highly inconsistent, with some reporting positive values for K1: Darby, M.; Isaac, E. (June 1974). "Magnetocrystalline anisotropy of ferro- and ferrimagnetics". IEEE Transactions on Magnetics. 10 (2): 259–304. Bibcode:1974ITM....10..259D. doi:10.1109/TMAG.1974.1058331.

- Chikazumi 1997, chapter 12

- Ye, Newell & Merrill 1994

Further reading

- Chikazumi, Sōshin (1997). Physics of Ferromagnetism. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-851776-9.

- Cullity, B. D.; Graham, C. D. (2008). Introduction to Magnetic Materials (2nd ed.). Wiley-IEEE Press. ISBN 978-0471477419.

- Daalderop, G. H. O.; Kelly, P. J.; Schuurmans, M. F. H. (1990). "First-principles calculation of the magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy of iron, cobalt, and nickel". Phys. Rev. B. 41 (17): 11919–11937. Bibcode:1990PhRvB..4111919D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.41.11919. PMID 9993644.

- Dunlop, David J.; Özdemir, Özden (1997). Rock Magnetism: Fundamentals and Frontiers. Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 0-521-32514-5.

- Landau, L. D.; Lifshitz, E. M.; Pitaevski, L. P. (2004) [First published in 1960]. Electrodynamics of Continuous Media. Course of Theoretical Physics. Vol. 8 (Second ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 0-7506-2634-8.

- Ye, Jun; Newell, Andrew J.; Merrill, Ronald T. (1994). "A re-evaluation of magnetocrystalline anisotropy and magnetostriction constants". Geophysical Research Letters. 21 (1): 25–28. Bibcode:1994GeoRL..21...25Y. doi:10.1029/93GL03263.

- Samad, Fabian; Hellwig, Olav (2023). "Determining the preferred directions of magnetisation in cubic crystals using symmetric polynomial inequalities". Emergent Scientist. 7. doi:10.1051/emsci/2023002.

- Krause, D. (1964). "Über die magnetische Anisotropieenergie kubischer Kristalle". Phys. Status Solidi B. 6. doi:10.1002/pssb.19640060110.