Magnus II of Norway

Magnus Haraldsson (Old Norse: Magnús Haraldsson; c. 1048 – 28 April 1069) was King of Norway from 1066 to 1069, jointly with his brother Olaf Kyrre from 1067. He was not included in official Norwegian regnal lists until modern times, but has since been counted as Magnus II.

| Magnus Haraldsson | |

|---|---|

| King of Norway | |

| Reign | 1066 – 28 April 1069 |

| Predecessor | Harald III |

| Successor | Olaf III |

| Co-ruler | Olaf III (from 1067) |

| Born | c. 1048 |

| Died | 28 April 1069 (aged 19–21) Nidaros, Norway |

| Issue | Haakon Magnusson of Norway |

| House | Hardrada |

| Father | Harald III of Norway |

| Mother | Tora Torbergsdatter |

| Religion | Catholicism |

A son of King Harald Hardrada, Magnus was in 1058 appointed nominal leader of an expedition into the Irish Sea while still only a child. He appears to have assisted Welsh ruler Gruffydd ap Llywelyn and Ælfgar, Earl of Mercia in their struggles against Wessex, although his primary objective may have been to assert control over Orkney. He later accompanied his father in Harald's campaign against Denmark in 1062, and was appointed regent and made king before Harald's fatal invasion of England in 1066. Magnus briefly ruled Norway alone thereafter, until his younger brother Olaf returned from England in 1067.

Magnus co-ruled with Olaf following his brother's return to Norway, but less than three years into his reign, Magnus became ill and died. His kingship has been downplayed in later history in part due to this. Magnus had only one child, Haakon Toresfostre who was king briefly after Olaf, but who also died young, and without issue.

Early life

Background

Magnus was born in 1048[1] or 1049.[2] He was the first of two sons of King Harald Hardrada, by his consort Tora Torbergsdatter.[2] There are no known skaldic poems written about Magnus, and he appears only briefly in the Norse sagas.[2] The author of Ágrip af Nóregskonungasögum describes him in passing as "a most handsome man."[3] While not mentioned anywhere in the sagas, Magnus appears in contemporary British sources around the year 1058 as the leader of a Norwegian expedition in the Irish Sea.[4]

Expedition to the West

In 1058, Magnus headed an expedition into the Irish Sea that sought to extend Norwegian authority in the region, the Norwegians siding with a faction that opposed the Norse-Gaelic king Echmarcach mac Ragnaill.[5] The expedition also appears to have supported a branch of the Norse-Gaelic dynasty of Ivar that opposed Irish king Diarmait mac Maíl na mBó.[6] Magnus commanded a fleet that, in addition to Norway, recruited men from Orkney, the Hebrides, and Dublin.[7] His forces were later active in Wales[8] and perhaps in England, and English chronicler John of Worcester associates the Norwegian fleet (along with the Welsh ruler Gruffydd ap Llywelyn), with returning the exiled Ælfgar, Earl of Mercia to power.[9] The Irish Annals of Tigernach goes further in claiming that Magnus's goal was to seize power in England, but this is not supported by Welsh and English sources[10] which also includes the Annales Cambriae and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.[11]

Magnus's campaign may have been part of his father's plans for an invasion of England, as control over the Kingdom of the Isles would have provided him with more troops.[5] Historian Kelly DeVries has moreover proposed that Harald may have wanted to test the situation in England before a possible invasion, only to find that he could not be at war with Denmark and England at the same time.[12] The expedition of Magnus never made significant landfall in England, but for English king Edward the Confessor it probably signalled renewed Norwegian ambitions from Harald Hardrada, who considered himself Edward's rightful heir. At the same time, the rise in power of Godwin, Earl of Wessex and his sons, in particular Harold Godwinson, had also started representing a threat to Harald's claim.[13]

On the other hand, historian Alex Woolf has suggested that the expedition originally may only have been intended for Orkney, and that in search for plunder it was followed by an expedition into the Irish Sea that by mere luck presented Magnus with the opportunity of raiding with Earl Ælfgar.[14] The exact year that Thorfinn Sigurdsson, Earl of Orkney died is not recorded anywhere, other than that it is stated in the Orkneyinga saga that it was in the later days of Harald Hardrada.[15] Thus, it may be that his death provoked Magnus's expedition, and that the expedition was the occasion on which Paul and Erlend Thorfinnsson, Thorfinn's successors as earls, submitted to Harald.[16] Woolf has also proposed that Magnus may have played some part in the war in Scotland in 1057–1058, perhaps supporting Máel Coluim mac Donnchada against Lulach.[17]

Kingship and death

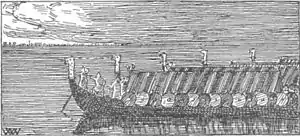

Magnus accompanied his father in Harald's campaign against Denmark in 1062. On his way to Denmark, Harald's fleet clashed with the fleet of Danish king Sweyn Estridsson in a major naval battle at Niså that resulted in Norwegian victory.[2] In 1066, after concluding peace with Sweyn Estridsson, Harald set out on his campaign of conquering England from Harold Godwinson. Before departing, he appointed Magnus as regent and king of Norway in his absence, and had his younger son Olaf accompany him on the expedition. After initial success in the Battle of Fulford, Harald was defeated and killed by Harold Godwinson in the Battle of Stamford Bridge. Olaf survived and returned to Norway with the remaining troops in early 1067, and was proclaimed king and co-ruler with his brother Magnus.[2]

Although it was intended for Magnus and Olaf to rule the kingdom jointly without division, in practice Olaf ruled over Viken (the south-eastern part of Norway), while Magnus controlled the Uplands and Trøndelag (the middle parts of Norway) along with Western Norway and Northern Norway. Despite this division, there are no signs of hostility between the brothers, and their relationship appears to have been peaceful.[2]

Having reigned for less than three years, Magnus became ill and died in Nidaros (Trondheim) on 28 April 1069. The sagas posit that Magnus died of ringworm, but modern scholars have proposed that he instead may have died of ergotism (poisoning by the Claviceps purpurea fungus).[2] Snorri Sturluson writes briefly in the Saga of Harald Hardrade that Magnus was "an amiable king and bewailed by the people."[18]

Magnus's kingship has been downplayed in later history partly due to his short tenure, and because most of it was together with his brother. The subsequently long reign of Olaf also contributed to overshadow Magnus's reign, combined with the fact that the later Norwegian royal dynasties only descended (or claimed descent) from Olaf.[2]

The king known today as Magnus VI (the first Norwegian king known to use regnal numbers) originally used the regnal number IV for himself in contemporary Latin letters, leaving out Magnus Haraldsson.[19] As the numbering system has seen changes in modern times, Magnus Haraldsson is today included as Magnus II.[2]

Family

Magnus had a son, Haakon Magnusson of Norway, who was probably born the same year that Magnus died. Haakon went on to claim what he considered his part of the kingdom (after his father) in 1093 when his uncle Olaf Kyrre died, and shared the kingdom with his cousin Magnus Barefoot (son of Olaf Kyrre). Similar to the reign of his father, Haakon's reign also ended abruptly after a short time as he died young in 1095.[2]

Footnotes

- "Magnus II Haraldsson". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- Krag, Claus. "Magnus 2 Haraldsson". Norsk biografisk leksikon (in Norwegian). Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Ágrip af Nóregskonungasögum, chapter 43

- Woolf 2007, p. 267.

- Gillingham 2004, p. 68.

- Gillingham 2004, p. 67.

- Barlow 1984, p. 201.

- Barlow 1984, p. 342.

- Abels & Bachrach 2001, p. 78.

- Jankulak & Wooding 2007, p. 163.

- Woolf 2007, p. 266.

- DeVries 1999, p. 67.

- Forte, Oram & Pedersen 2005, p. 209.

- Woolf 2007, p. 268.

- Woolf 2007, p. 309.

- Woolf 2007, pp. 267–268.

- Woolf 2007, pp. 268–269.

- Saga of Harald Hardrade, chapter 105

- Skaare 1995, p. 332.

References

- Primary sources

- Sturluson, Snorri (c. 1230). Saga of Harald Hardrade (in Heimskringla). English translation: Samuel Laing (London, 1844).

- Ágrip af Nóregskonungasögum (c. 1180s). English translation: M. J. Driscoll (London, 2008).

- Modern literature

- Abels, Richard Philip; Bachrach, Bernard Stanley (2001). The Normans and Their Adversaries at War. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9780851158471.

- Barlow, Frank (1984) [1970]. Edward the Confessor. University of California. ISBN 978-0-520-05319-9.

- DeVries, Kelly (1999). The Norwegian Invasion of England in 1066. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 9780851157634.

- Forte, Angelo; Oram, Richard Duncan; Pedersen, Frederik (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge University. ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- Gillingham, John (2004). "Proceedings of the Battle Conference 2003". Anglo-Norman Studies. Boydell. 26. ISSN 0954-9927.

- Jankulak, Karen; Wooding, Jonathan M. (2007). Ireland and Wales in the Middle Ages. Four Courts. ISBN 978-0-520-05319-9.

- Skaare, Kolbjørn (1995). Norges mynthistorie. Vol. 1. Universitetsforlaget. ISBN 82-00-22666-2.

- Woolf, Alex (2007). Pictland to Alba 789–1070. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University. ISBN 978-0-7486-1234-5.