Claviceps purpurea

Claviceps purpurea is an ergot fungus that grows on the ears of rye and related cereal and forage plants. Consumption of grains or seeds contaminated with the survival structure of this fungus, the ergot sclerotium, can cause ergotism in humans and other mammals.[1][2] C. purpurea most commonly affects outcrossing species such as rye (its most common host), as well as triticale, wheat and barley. It affects oats only rarely.

| Claviceps purpurea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Sordariomycetes |

| Order: | Hypocreales |

| Family: | Clavicipitaceae |

| Genus: | Claviceps |

| Species: | C. purpurea |

| Binomial name | |

| Claviceps purpurea | |

| Ecological races | |

| |

Life cycle

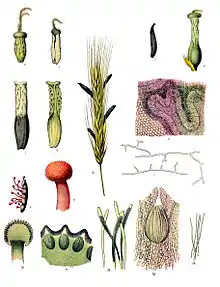

An ergot kernel called Sclerotium clavus develops when a floret of flowering grass or cereal is infected by an ascospore of C. purpurea. The infection process mimics a pollen grain growing into an ovary during fertilization. Because infection requires access of the fungal spore to the stigma, plants infected by C. purpurea are mainly outcrossing species with open flowers, such as rye (Secale cereale) and Alopecurus.

The proliferating fungal mycelium then destroys the plant ovary and connects with the vascular bundle originally intended for feeding the developing seed. The first stage of ergot infection manifests itself as a white soft tissue (known as Sphacelia segetum) producing sugary honeydew, which often drops out of the infected grass florets. This honeydew contains millions of asexual spores (conidia) which are dispersed to other florets by insects or rain. Later, the Sphacelia segetum convert into a hard dry Sclerotium clavus inside the husk of the floret. At this stage, alkaloids and lipids (e.g. ricinoleic acid) accumulate in the Sclerotium.

When a mature Sclerotium drops to the ground, the fungus remains dormant until proper conditions trigger its fruiting phase (onset of spring, rain period, need of fresh temperatures during winter, etc.). It germinates, forming one or several fruiting bodies with head and stipe, variously colored (resembling a tiny mushroom). In the head, threadlike sexual spores (ascospores) are formed in perithecia, which are ejected simultaneously, when suitable grass hosts are flowering. Ergot infection causes a reduction in the yield and quality of grain and hay produced, and if infected grain or hay is fed to livestock it may cause a disease called ergotism.

Polistes dorsalis, a species of social wasps, have been recorded as a vector of the spread of this particular fungus. During their foraging behavior, particles of the fungal conidia get bound to parts of this wasp's body. As P. dorsalis travels from source to source, it leaves the fungal infection behind.[3] Insects, including flies and moths, have also been shown to carry conidia of Claviceps species, but if insects play a role in spreading the fungus from infected to healthy plants is unknown.[4]

Intraspecific variations

_-Osterloh_Nr._42-_-Brendel_10_g%252C_2-_(2).jpg.webp)

Early scientists have observed Claviceps purpurea on other Poaceae as Secale cereale. 1855, Grandclement[5] described ergot on Triticum aestivum. During more than a century scientists aimed to describe specialized species or specialized varieties inside the species Claviceps purpurea.

- Claviceps microcephala Tul. (1853)

- Claviceps wilsonii Cooke (1884)

Later scientists tried to determine host varieties as

- Claviceps purpurea var. agropyri

- Claviceps purpurea var. purpurea

- Claviceps purpurea var. spartinae

- Claviceps purpurea var. wilsonii.

Molecular biology has not confirmed this hypothesis but has distinguished three groups differing in their ecological specificity.[6]

- G1—land grasses of open meadows and fields;

- G2—grasses from moist, forest, and mountain habitats;

- G3 (C. purpurea var. spartinae)—salt marsh grasses (Spartina, Distichlis).

Morphological criteria to distinguish different groups: The shape and the size of sclerotia are not good indicators because they strongly depend on the size and shape of the host floret. The size of conidia can be an indication but it is weak and it is necessary to pay attention to that, due to osmotic pressure, it varies significantly if the spores are observed in honeydew or in water. The sclerotial density can be used as the groups G2 and G3 float in water.

The compound of alkaloids is also used to differentiate the strains.

Host range

Pooideae

Agrostis canina, Alopecurus myosuroides (G2), Alopecurus arundinaceus (G2), Alopecurus pratensis, Bromus arvensis, Bromus commutatus, Bromus hordeaceus (G2), Bromus inermis,[7] Bromus marginatus, Elymus tsukushiense, Festuca arundinacea,[8] Elymus repens (G1), Nardus stricta, Poa annua (G2), Phleum pratense, Phalaris arundinacea (G2), Poa pratensis (G1), Stipa.

Arundinoideae

Chloridoideae

Spartina, Distichlis (G3)

Panicoideae

Epidemiology

Claviceps purpurea has been known to humankind for a long time, and its appearance has been linked to extremely cold winters that were followed by rainy springs.

The sclerotial stage of C. purpurea conspicuous on the heads of ryes and other such grains is known as ergot. Sclerotia germinate in spring after a period of low temperature. A temperature of 0-5 °C for at least 25 days is required. Water before the cold period is also necessary.[9] Favorable temperatures for stroma production are in the range of 10-25 °C.[10] Favorable temperatures for mycelial growth are in the range of 20-30 °C with an optimum at 25 °C.[10]

Sunlight has a chromogenic effect on the mycelium with intense coloration.[11]

Effects

The disease cycle of the ergot fungus was first described in 1853,[12] but the connection with ergot and epidemics among people and animals was reported already in a scientific text in 1676.[13] The ergot sclerotium contains high concentrations (up to 2% of dry mass) of the alkaloid ergotamine, a complex molecule consisting of a tripeptide-derived cyclol-lactam ring connected via amide linkage to a lysergic acid (ergoline) moiety, and other alkaloids of the ergoline group that are biosynthesized by the fungus.[14] Ergot alkaloids have a wide range of biological activities including effects on circulation and neurotransmission.[15]

Ergotism is the name for sometimes severe pathological syndromes affecting humans or animals that have ingested ergot alkaloid-containing plant material, such as ergot-contaminated grains. Monks of the order of St. Anthony the Great specialized in treating ergotism victims[16] with balms containing tranquilizing and circulation-stimulating plant extracts; they were also skilled in amputations. The common name for ergotism is "St. Anthony's Fire",[16] in reference to monks who cared for victims as well as symptoms, such as severe burning sensations in the limbs.[17] These are caused by effects of ergot alkaloids on the vascular system due to vasoconstriction of blood vessels, sometimes leading to gangrene and loss of limbs due to severely restricted blood circulation.

The neurotropic activities of the ergot alkaloids may also cause hallucinations and attendant irrational behaviour, convulsions, and even death.[14][15] Other symptoms include strong uterine contractions, nausea, seizures, and unconsciousness. Since the Middle Ages, controlled doses of ergot were used to induce abortions and to stop maternal bleeding after childbirth.[18] Ergot alkaloids are also used in products such as Cafergot (containing caffeine and ergotamine[18] or ergoline) to treat migraine headaches. Ergot extract is no longer used as a pharmaceutical preparation.

Ergot contains no lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) but rather ergotamine, which is used to synthesize lysergic acid, an analog of and precursor for synthesis of LSD. Moreover, ergot sclerotia naturally contain some amounts of lysergic acid.[19]

Culture

Potato dextrose agar, wheat seeds or oat flour are suitable substrates for growth of the fungus in the laboratory.[20]

Agricultural production of Claviceps purpurea on rye is used to produce ergot alkaloids. Biological production of ergot alkaloids is also carried out by saprophytic cultivations.

Speculations

During the Middle Ages, human poisoning due to the consumption of rye bread made from ergot-infected grain was common in Europe. These epidemics were known as Saint Anthony's fire,[16] or ignis sacer.

Gordon Wasson proposed that the psychedelic effects were the explanation behind the festival of Demeter at the Eleusinian Mysteries, where the initiates drank kykeon.[21]

Linnda R. Caporael posited in 1976 that the hysterical symptoms of young women that had spurred the Salem witch trials had been the result of consuming ergot-tainted rye.[22] However, her conclusions were later disputed by Nicholas P. Spanos and Jack Gottlieb, after a review of the historical and medical evidence.[23] Other authors have likewise cast doubt on ergotism having been the cause of the Salem witch trials.[24]

The Great Fear in France during the Revolution has also been linked by some historians to the influence of ergot.

British author John Grigsby claims that the presence of ergot in the stomachs of some of the so-called 'bog-bodies' (Iron Age human remains from peat bogs N E Europe such as Tollund Man), reveals that ergot was once a ritual drink in a prehistoric fertility cult akin to the Eleusinian Mysteries cult of ancient Greece. In his book Beowulf and Grendel he argues that the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf is based on a memory of the quelling of this fertility cult by followers of Odin. He states that Beowulf, which he translates as barley-wolf, suggests a connection to ergot which in German was known as the 'tooth of the wolf'.

An outbreak of violent hallucinations among hundreds of residents of Pont St. Esprit in 1951 in the south of France has also been attributed to ergotism.[25] Seven people died.

See also

References

- "ergot definition". mondofacto. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03.

- "ergot". Dorland's Medical Dictionary. Archived from the original on September 10, 2009. Retrieved August 9, 2017 – via Merck Source.

- Hardy, Tad N. (September 1988). "Gathering of Fungal Honeydew by Polistes spp. (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) and Potential Transmission of the Causal Ergot Fungus". The Florida Entomologist. 71 (3): 374–376. doi:10.2307/3495447. JSTOR 3495447.

- Butler, M.D.; Alderman, S. C.; Hammond, P.C.; Berry, R. E. (2001). "Association of Insects and Ergot (Claviceps purpurea) in Kentucky Bluegrass Seed Production Fields". J. Econ. Entomol. 94 (6): 1471–1476. doi:10.1603/0022-0493-94.6.1471. PMID 11777051. S2CID 8725020.

- Mr Gonod d'Artemare (1860). "Note sur l'ergot du froment". Bulletin de la Société botanique de France: 771.

- Pažoutová S.; Olšovská J.; Linka M.; Kolínská R.; Flieger M. (2000). "Chemoraces and habitat specialization of Claviceps purpurea populations". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 66 (12): 5419–5425. Bibcode:2000ApEnM..66.5419P. doi:10.1128/aem.66.12.5419-5425.2000. PMC 92477. PMID 11097923.

- Eken C.; Pažoutová S.; Honzátko A.; Yildiz S. (2006). "First report of Alopecurus arundinaceus, A. myosuroides, Hordeum violaceum and Phleum pratense as hosts of Claviceps purpurea population G2 in Turkey". J. Plant Pathol. 88: 121.

- Douhan G. W.; Smith M. E.; Huyrn, K. L.; Yildiz S. (2008). "Multigene analysis suggests ecological speciation in the fungal pathogen Claviceps purpurea". Molecular Ecology. 17 (9): 2276–2286. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03753.x. PMC 2443689. PMID 18373531.

- Kichhoff H (1929). "Beiträge zur Biologie und Physiologie des Mutterkornpilzes". Centralblat. Bakteriol. Parasitenk. Abt. II. 77: 310–369.

- Mitchell D.T. (1968). "Some effects of temperature on germination of sclerotia in Claviceps purpurea". Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 51 (5): 721–729. doi:10.1016/s0007-1536(68)80092-0.

- McCrea A (1931). "The reactions of Claviceps purpurea to variations of environment" (PDF). Am. J. Bot. 18 (1): 50–78. doi:10.2307/2435724. hdl:2027.42/141053. JSTOR 2435724.

- Tulasne, L.-R. (1853) Mémoire sur l'ergot des glumacéses Ann. Sci. Nat. (Parie Botanique), 20 5-56

- Dodart D. (1676) Le journal des savans, T. IV, p. 79

- Tudzynski P, Correia T, Keller U (2001). "Biotechnology and genetics of ergot alkaloids". Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 57 (5–6): 4593–4605. doi:10.1007/s002530100801. PMID 11778866. S2CID 847027.

- Eadie MJ (2003). "Convulsive ergotism: epidemics of the serotonin syndrome?". Lancet Neurol. 2 (7): 429–434. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(03)00439-3. PMID 12849122. S2CID 12158282.

- J. Heritage; Emlyn Glyn Vaughn Evans; R. A. Killington (1999). Microbiology in Action. Cambridge University Press. p. 115.

- St. Anthony's Fire -- Ergotism

- Untersuchungen über das Verhalten der Secalealkaloide bei der Herstellung von Mutterkornextrakten. Labib Farid Nuar. Universität Wien - 1946 - (University of Vienna)

- Correia T, Grammel N, Ortel I, Keller U, Tudzynski P (2001). "Molecular cloning and analysis of the ergopeptine assembly system in the ergot fungus Claviceps purpurea". Chem. Biol. 10 (12): 1281–1292. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.11.013. PMID 14700635.

- Mirdita, Vilson (2006). Genetische Variation für Resistenz gegen Mutterkorn (Claviceps purpurea [Fr.] Tul.) bei selbstinkompatiblen und selbstfertilen Roggenpopulationen (Thesis). Archived from the original on 2009-09-09. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- Gordon Wasson, The Road To Eleusis: Unveiling The Secret of The Mysteries (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1977) ISBN 0151778728

- Caporael LR (April 1976). "Ergotism: the satan loosed in Salem?". Science. 192 (4234): 21–6. Bibcode:1976Sci...192...21C. doi:10.1126/science.769159. PMID 769159. Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- Spanos NP, Gottlieb J (December 1976). "Ergotism and the Salem Village witch trials". Science. 194 (4272): 1390–4. Bibcode:1976Sci...194.1390S. doi:10.1126/science.795029. PMID 795029.

- Woolf A (2000). "Witchcraft or mycotoxin? The Salem witch trials". J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 38 (4): 457–460. doi:10.1081/CLT-100100958. PMID 10930065. S2CID 10469595.

- Gabbai, J.; Lisbonne, L. & Pourquier, F. (September 1951). "Ergot poisoning at Pont St. Esprit". Br Med J. 15 (4732): 2276–2286. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4732.650. PMC 2069953. PMID 14869677.

External links

- Claviceps purpurea - Ergot Alkaloid

- Ergot article from North Dakota State University, 2002

- PBS Secrets of the Dead: "The Witches Curse" (concerning the Salem trials and ergot) Archived 2014-04-19 at the Wayback Machine

- New England Journal of Medicine - Dopamine Agonists and the Risk of Cardiac-Valve Regurgitation

- Linnda Caporeal's article "Ergotism: The Satan Loosed in Salem?