Mahmoud Reza Banki

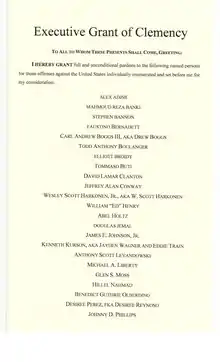

Mahmoud Reza Banki (Persian: محمودرضا بانکی; born 1976) is an Iranian-American scientist, management consultant and startup executive (CFO & CSO). Born in Tehran, Iran, Banki immigrated to the US to attend college and became a naturalized US citizen in the 1990s. In January 2010, Banki was arrested and charged with violating US sanctions against Iran by the United States Attorney's office in New York City. Ultimately Banki won his case on appeal, and it was permanently closed in July 2012. Banki spoke about his case at a TED Talk in 2014,[1] presenting a case for change in criminal justice.[2] As of 2015 a documentary film about the case was being made.[3] In The Moth podcast released January 2017, Banki spoke to the personal toll of the ordeal.[4] Banki has also spoken before various audiences for the cause of improving the criminal justice system.[5] As of 2022, Banki was Chief Financial Officer and Chief Strategy Officer at leading streaming company Tubi. [6] On January 20, 2021, Banki received a full and unconditional pardon from the President of the United States.[7]

Mahmoud Reza Banki (M. Reza Banki) | |

|---|---|

| Born | |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Occupation(s) | Scientist, consultant |

| Website | http://www.rezastory.com |

Biography

After migrating to America, Banki graduated from the University of California at Berkeley and subsequently earned a PhD in chemical engineering with a focus on biotechnology from Princeton University and has published numerous scientific articles[8] and a biotechnology book.[9] After completing his PhD, he worked as a management consultant at the New York City office of McKinsey & Company.[10] In January 2010, Banki was arrested and prosecuted by the United States Attorney's office in New York City. He was charged with violating US sanctions against Iran. He spent 22 months in prison before winning his case on appeal in the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, with all charges against him related to the sanctions being dismissed. After his release Banki earned a Master of Business Administration from the University of California, Los Angeles, and worked at NBCUniversal.

United States v. Banki case

Background

Banki's family lived in Iran and through the early 2000s with his parents' marriage falling apart, the family decided to send a portion of the family assets to the US.[11] Between 2006 and 2009 Banki's family sent proceeds of his parents' divorce settlement (approximately $3.4 million) to him, from Iran to the US. The money came into a single bank account at Bank of America, over multiple transfers through an informal money transfer systems which the defendant argued was legal and the only means of sending money out of Iran at the time. Banki used the majority of this money to purchase an apartment in downtown Manhattan.

Prosecutors argued that over this three-year period Banki had violated the sanctions imposed by the US on Iran. The indictment accused Banki of violating the sanctions law, running an informal underground bank, and helping "manage, supervise, operate, and conduct" an unlicensed money transmittal service through which he directly or indirectly facilitated and violated the Iran sanctions. In essence, the charges against Banki stemmed from prosecution allegations that he, as an American citizen, had violated US sanctions on Iran.

Sanctions history

The United States enforces sanctions against several countries worldwide.[12] These sanctions are instituted by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) under the Department of Treasury of the United States.

US treasury's OFAC designates family money as exempt from the sanctions law.[13]

A detailed letter by former head of Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), Richard Newcomb, to the court during the case of US v. Banki outlined the sanctions regiment and intent; undermining the prosecutor's case against Banki as not being in line with the practices of OFAC or the intent of the sanctions. Nor were the charges in line with the agency's approach while Richard Newcomb was head of the agency:

"The underlying purpose for these multiple U.S. economic sanctions programs against Iran was to target the Government with the use of economic methods to change the behavior of the leadership in Iran toward the United States and the international community at large, and to thwart Iran's support for and funding of terrorism, its efforts to disrupt the Middle East Peace Process and its development of weapons of mass destruction. Central to the effort was to direct and focus the sanctions impact on the Government of Iran, its leadership, its various agencies, instrumentalities, controlled entities and support structure, including Iran's Revolutionary Guard Corps, and other such organizations necessary for the support and continuation of the current Governmental hierarchy. The industrial and commercial sectors - oil and gas, financial, manufacturing and other sectors that contribute significantly to Iran's economy and the Government's ability to continue its threatening behavior were also of primary concern. The program goal was never intended to target the Iranian people. The Iranian Diaspora is large. As many as 4 million or more Iranians live as expats around the world. It is estimated that there are as many as 800,000 Iranian nationals currently resident in the United States as dual nationals, green card holders or with other visa status. A very large percentage are supporters of U.S. policy toward Iran, and it is the goal of the U.S. government to continue cultivating that support while isolating the government of Iran. In virtually all economic sanctions programs administered by OFAC (with the exception of the 1963 program against Cuba where Cuban nationals were also included as targets), including the Iran sanctions program, it was always understood that there was a dual goal and purpose - to bring as much economic pressure as possible to bear on the intended target without causing unintended hardship and suffering on the civilian population, the very people whose support and assistance the U.S. and the international community will need if and when a successor government emerges."[14]

Arrest, indictment and charges

On January 7th, 2010, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents authorized by a grand jury with a search and arrest warrant entered the residence of Mahmoud Reza Banki in New York City and arrested him.[15] He was arraigned before Judge John F. Keenan on an indictment charging him with three counts: 1. Conspiracy to violate the U.S.-imposed Iran sanctions and conspiracy to run an unlicensed money transmittal system, 2. Violation of the Iran sanctions, and 3. Running of an unlicensed money transmittal business.[16] The indictment accused Banki of receiving $4.7 million in violation of the Iran sanctions. Prosecutors filed a superseding indictment later changing the amount to $3.4 million and adding two false statement charges to the three initial charges.[17]

Banki was denied bail despite multiple attempts.[18] He was held in high and maximum security [19] detention facilities pending trial. Judge John F. Keenan asserted that there was "no combination of conditions would ensure Banki's appearance in court" and denied bail multiple times despite securing guarantees of millions of dollars in bond. Nine attorneys and close friends volunteered to put up their homes as collateral on Banki's behalf for his bail package. But the judge did not see any monetary amount that could satisfy the bail conditions in his opinion.

Trial at the District Court and forfeiture

The indictment charging Banki argued that Banki should have gotten authorization in the form of a license for the money he received: "(vi) Under the ITR, any United States person who wishes to engage in a transaction otherwise prohibited by the ITR must first file an application for a license and receive approval from OFAC. 31 C.F.R. §§ 56.600, 560.501, and 501.801.".[16]

Banki did not have a license for the money he received. Judge John F. Keenan denied the Banki's defense request to instruct the jury on the law that specifically permits family money as an exception to the sanctions law, permitting such transfers without the need for a license: "However, U.S. depository institutions are permitted to handle funds transfers, through intermediary third-country banks, to or from Iran or for the direct or indirect benefit of the Government of Iran or a person in Iran, arising from several types of underlying transactions, including: a) a noncommercial family remittance; b) an exportation to Iran or importation from Iran of information and informational materials; c) a travel-related remittance; d) a payment for the shipment of a donation of articles to relieve human suffering; or e) a transaction authorized by OFAC through a specific or general license.".[13]

On May 10, 2010, a three-week trial commenced where Second Circuit District judge John F. Keenan presided. The trial concluded on June 4 when the jury returned a guilty verdict on all five counts, albeit, guilty on a lesser charge of aiding and abetting rather than running a sanctions violation money transmittal system.[20]

On June 7, 2010, despite the superseding indictment charge of $3.4 million, the same jury agreed to forfeit one bank account associated with a $6,000 transaction as the proceeds of the charges and the guilty verdict. The jury ruled that Mahmoud Reza Banki's other assets including the apartment he had purchased with the family funds he had received was not a direct proceeds of any crime and not forfeitable.

Judge John F. Keenan overruled the jury only in the case of the forfeiture verdict on the basis that the jury might have been "confused" and awarded the government prosecutors a money judgment order, essentially ignoring the jury verdict on forfeiture and awarding the US Attorney's office $3.4 million, to be paid by Banki.[21] This would have been the same as if the jury had come to the decision of full forfeiture of all of Banki's assets.

The defense objections throughout the trial were overruled. One such overruling was the judge's decision not to allow for jury instructions on the family money exception from the sanctions law. Essentially, the jury was not told that transfer of family money is legal; that family money can be sent to and received from Iran and is an exception in the US sanctions law against Iran. This would become a material issue at the appellate level and the primary reason for the reversal of the charges.

Judge Keenan also did not allow the defense to call Richard Newcomb, former head of OFAC, to testify as an expert witness on the sanctions charges despite his qualifications: he had been head of OFAC for 17 years (from 1987 to 2004), where he was the author of the sanctions law. Richard Newcomb was not only the author of the underlying sanctions regulations but in his capacity as head of OFAC he had also been in charge of enforcing the sanctions law not just against Iran but all countries US had sanctions against.[14]

Sentencing and imprisonment

During sentencing, over 120 letters of support were sent to Judge Keenan to ask for leniency. Among those were letters from Nobel Peace Laureate Shirin Ebadi and ex-Director of the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) Richard Newcomb. In a lengthy letter, Richard Newcomb made the case for Banki's innocence of the sanctions charges and highlighted that through Newcomb's administration of the sanctions program in the US the program was "never intended to target the Iranian people" and that "the Iranian-American community commonly and openly uses remittance forwarding service providers, including hawalas to move family funds back and forth between the United States and Iran, typically with no penalty, civil or criminal."[14][22]

On August 16, 2010, Judge Keenan sentenced Banki to 30 months in prison.[23]

Shortly after being sentenced Banki filed for appeal. The Iranian American Bar Association along with 10 other advocacy and civil rights groups filed a separate amicus brief with the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. The brief argued that U.S.-Iran sanctions "are not aimed at the Iranian people, and therefore they contain exemptions permitting certain humanitarian transactions and family remittances."[24]

For about 11 months (from January 7, 2010, through December 1, 2010) Banki was held in high and maximum security detention centers in Manhattan and Brooklyn (MCC and MDC).[25] For the month of December in 2010, Banki was transferred to the Taft Correctional Institute's deportation prison outside of Bakersfield in California. In January 2011, Banki was transferred to the lower security Taft prison where he remained pending the appellate decision. Upon release Banki had served 665 days, nearly 22 months in prison.

Appellate reversal

On October 24, 2011, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled in favor of Banki and reversed the sanctions charges against him. Judge Keenan's court-ordered Banki's release 10 days later on November 2, 2011.[26]

The appellate court ruled that Judge John F. Keenan had erred at trial; in denying Banki's defense request to instruct the jury on the law that specifically exempts family money as an exception to the sanctions law, permitting such transfers without the need for a license. The final appellate court brief stated: "Banki's conviction [on the sanctions charges] cannot stand".[27]

Prosecutors reopened the case to pursue a retrial in February 2012. However, after a few months of delay and the assignment of a new judge, the case was closed criminally with no option for future civil or criminal prosecution. Rather than pay for the high cost of a second criminal defense trial, Banki agreed to relinquish $710k of his assets. In exchange, prosecutors agreed that Banki was not guilty of the sanctions charges without going through a second trial and that they would end pursuing the case further in criminal or civil courts.

The case was permanently closed on July 24, 2012, with the final word being Banki's appellate win and that Banki was not guilty of the sanctions charges for which he had been arrested and for which he served 22 months in prison. In the final court hearing, Banki's prison record was cleared. During the hearing, Banki said he had lived through "the darkest hours" of his life while in prison. "I watched my life pass me by. Those days will never be replaced". Judge Engelmayer in clearing Banki's prison record called him a "talented man, even brilliant".[28] The judge also stated: ". . . the damage to Mr. Banki's life brought about by his lengthy incarceration, occasioned by his confinement, cannot be measured only by the 22 months in which he lost his liberty and which he cannot get back".[21]

Aftermath

Since his release, Banki has completed a master's in business administration from UCLA Anderson School of Management. Banki spoke about his case for the first time publicly at a TED Conference at UCLA in 2014 in an effort to raise awareness about the justice system. He also spoke about the uncertain life path he now faces in the US and the difficulty he faces in finding employment due to his continued status as a felon despite his appellate win.[1][29] There are plans for a documentary of his story.[3]

Banki's case raises questions not just about the ambiguity and impracticality of the sanctions laws for Iranian-Americans but speaks to the broader impact that the current criminal justice system can have on the path of a "success story".[11]

With support from 13 Congressmen and a Senator, Banki filed for a Presidential Pardon.[29][30] As of 2022, Banki was Chief Financial Officer and Chief Strategy Officer at leading streaming company Tubi. [6] Banki was granted a full pardon on January 20, 2021.[7]

References

- Mahmoud Reza Banki's TED talk at UCLA

- My 665 days in prison

- U.S. v Banki Documentary

- "From Princeton to Prison: The Rise and Fall of My American Dream" by Mahmoud Reza Banki, January 10, 2017

- Events at which Banki has spoken

- "AVOD Leader Tubi's Executive Leadership"

- "Statement from the Press Secretary Regarding Executive Grants of Clemency". whitehouse.gov. January 20, 2021 – via National Archives.

- Mahmoud Reza Banki Scientific Publications

- Banki, Mahmoud Reza (2009-06-28). FAST AND CHEAP PROTEIN PURIFICATION: Economical alternatives to conventional chromatography-based recombinant protein purification. VDM Verlag. ISBN 978-3-639-15443-6.

- Mahmoud Reza Banki LinkedIn profile

- "To Defendant, a U.S. Success Story; to Prosecutors, a Money Broker to Iran" by Benjamin Weiser, New York Times, May 12, 2010

- "United States Embargoes"

- "What you need to know about U.S. Economic Sanctions", by U.S. Department of the Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control

- Former Head of OFAC's letter in support of Mahmoud Reza Banki

- "Manhattan U.S. Attorney Charges Management Consultant For Criminal Violations Of Iran Trade Embargo", January 7, 2010

- Indictment against Mahmoud Reza Banki

- Superseding Indictment against Mahmoud Reza Banki

- Neumeister, Larry (January 21, 2010). "NYC consultant denied bail in Iran trade case". Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 21, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- Incarceration in the United States Security Levels

- "Immigrant Convicted of Violating Iran Embargo", by Benjamin Weiser, New York Times, June 4, 2010

- Court transcript: Case: 10-3381; Southern District of New York

- "IABA And Partner Organizations File Amicus Brief in United States v. Banki" Iranian American Bar Association

- "Man Gets 2 ½ Years for Breaking Iran Embargo" by Benjamin Weiser, New York Times, August 16, 2010

- Brief of Amici Curiae In Support of Defendant-Appellant Mahmoud Reza Banki

- Bureau of Prisons Facilities

- "2nd Circ. Nixes Conviction For Iran Money Transfer System" By Abigail Rubenstein Law360 October 24, 2011

- US Court of Appeals Decision

- "Banki told debt to society overpaid" Iran Times

- Neumeister, Larry (December 28, 2016). "Cleared of violating Iran sanctions, man hopes for pardon". Associated Press The Big Story. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- Presidential Pardon Efforts