Makhnovshchina

The Makhnovshchina (Ukrainian: Махновщина, romanized: Makhnovshchyna) was a mass movement to establish anarchist communism in southern and eastern Ukraine during the Ukrainian War of Independence of 1917–1921. Named after Nestor Makhno, the commander-in-chief of the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine, its aim was to create a system of free soviets that would manage the transition towards a stateless and classless society.

| Part of a series on the |

| Makhnovshchina |

|---|

|

The Makhnovist movement first gained ground in the wake of the February Revolution, when it established a number of agricultural communes in Makhno's home town of Huliaipole. After siding with the Bolsheviks during the Ukrainian–Soviet War, the Makhnovists were driven underground by the Austro-German invasion and waged guerrilla warfare against the Central Powers throughout 1918. After the insurgent victory at the Battle of Dibrivka, the Makhnovshchina came to control much of Katerynoslav province and set about constructing anarchist-communist institutions. A Regional Congress of Peasants, Workers and Insurgents was convened to organise the region politically and economically, with a Military Revolutionary Council being established as the movement's de facto executive organ.

Surrounded on all sides by different enemies, the Makhnovist line in the battle for the Donbas eventually fell to the advancing White movement in June 1919. The Makhnovists were subsequently driven into a retreat to Kherson, where they reorganised their military and led a successful counteroffensive against the Whites at the Battle of Peregonovka. With the White advance defeated, the Makhnovists came to control most of southern and eastern Ukraine in late 1919, even taking over a number of large industrial cities, despite being a predominantly peasant movement.

The Makhnovist control over the region was brought to an end when the Red Army invaded Ukraine in January 1920, initiating the Bolshevik–Makhnovist conflict. The Makhnovists waged a guerrilla war against the forces of the Red Terror and war communism, supported in large part by their peasant base. Although a peace was briefly secured by the two factions, with the Starobilsk agreement, in order to combat the remnants of the White movement, the Makhnovists were again attacked by the Red Army (USSR) and eventually defeated by August 1921. Leading Makhnovists were either driven into exile, defeated by the USSR or captured and killed by the Red Army.

Etymology and orthography

The term "Makhnovshchina" (Ukrainian: Махновщина, romanized: Makhnovshchyna) can be loosely translated as the "Makhno movement",[1] referring to the mass movement of social revolutionaries that supported the anarchist Nestor Makhno and his Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine (RIAU).[2]

The area controlled by the RIAU also came to be known as "Makhnovia"[3] (Ukrainian: Махновія; Russian: Махновия), a term used primarily in Soviet historiography.[4] This "Makhnovist territory"[5] or "Makhnovist region"[6] was alternatively referred to as a "liberated zone",[7] "liberated region",[8] "liberated area",[9] or "autonomous area".[10]

In June 1919, the Bolsheviks began to refer to the Makhnovist territory as the "independent anarchist republic of Huliaipole", in calls for the Makhnovshchina's abolition.[11] According to Bolshevik sources, that month's Planned Fourth Regional Congress intended to assert the region's independence and establish the "Priazov-Donets Republic"[12] or a "libertarian republic of Makhnovia".[6] Later, during their alliance with the Bolsheviks in October 1920, the Makhnovists insisted on terms allowing for the establishment of an "Autonomous Republic of Free Soviets" in the region.[13]

History

Background

What became the territory of the Makhnovshchina was centered in the region of Zaporizhzhia, which had previously been inhabited by Cossacks before its conquest by the Russian Empire.[14] Rechristened as the province of Katerynoslav, land largely came to be used for agriculture, leading to the rise of a landed nobility and a middle-peasant class known as the kulaks, many of whom were Black Sea Germans. The region's poor peasants attempted to resist Pyotr Stolypin's agrarian reforms, which threatened to break up their traditional communes, but by the 20th century the region had been thoroughly integrated into the grain market and came to export nearly half of its wheat each year.[15]

As the price of land was raised in order to prevent poor peasants from buying it, they became actively hostile to the concentration of land ownership by the pomeshchiks and kulaks.[16] Supported by their local governments, peasants resolved to found their own agricultural cooperatives and began trading their grain in a system of market socialism. This eventually led to the development of an agricultural industry in Katerynoslav, which produced almost a quarter of the Russian Empire's agricultural machinery and developed the region's settlements into small industrial centers. The development of industry brought together the peasantry and proletariat for the first time, with peasants often moving to centers of industry to become wage-earners and then back to their villages during times of industrial crisis.[17] This also caused the region to become quite ethnically diverse, with Ukrainians, Russians, Germans, Jews and Greeks all settled alongside each other. The region's common language soon became Russian and eventually, much of its Ukrainian population stopped speaking the Ukrainian language.[5]

Due in part to the diversity of the region's peasantry, the local Jewish population faced relatively little antisemitism, in comparison to the Jewish communities living in right-bank Ukraine.[18] It was young Jews that eventually formed the nucleus of the nascent Ukrainian anarchist movement,[19] which became a leading force during the 1905 Revolution in Ukraine.[20] The town of Huliaipole saw strike actions and a series of robberies, carried out by a group of young anarchist-communists known as the Union of Poor Peasants.[21] The group was eventually caught and its leading members arrested, with many of them being sentenced to the death penalty or life imprisonment.[22]

Revolution (February 1917 – February 1918)

In the wake of the February Revolution, Ukrainian intellectuals around Mykhailo Hrushevsky established the Central Council of Ukraine, which initially sought freedom of the press and education in the Ukrainian language, and eventually declared the autonomy of the Ukrainian People's Republic.[23] In concert with the emergence of the movement for Ukrainian nationalism, largely made up of social democrats and socialist revolutionaries, the Ukrainian anarchist movement also began to experience a revival, catalyzed by the return of Nestor Makhno from his imprisonment in Moscow.[24]

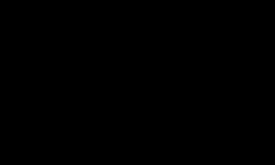

With Makhno as its leading figure, the anarchist movement in Huliaipole established a peasants' union, seized control of the town from the local provisional government and established a Soviet in its place, laying the foundations for the implementation of anarcho-communism.[25] According to Michael Malet, Huliaipole "was moving leftwards at a faster pace than elsewhere", with the town successfully organizing a May Day demonstration and even declaring its support for the workers' uprising in Petrograd, while the Oleksandrivsk Soviet still supported the Provisional Government.[26] The nascent Makhnovist movement undertook the seizure of land from the pomeshchiks and kulaks in Huliaipole and redistributed it to the peasantry, aiming to abolish the concentration of land ownership. By the summer of 1917, the town's peasants had stopped paying rent and had brought the land largely under the control of a land trust, which prevented landlords from selling off livestock or farming equipment.[27]

In August 1917, the Ukrainian Central Council and Russian Provisional Government reached an agreement on the position of the Russia–Ukraine border, which placed Katerynoslav within the territory of the Russian Republic, a decision which was rejected by the province's anarchist movement.[28] Viktor Chernov, the Russian Minister of Agriculture, attempted to implement a comprehensive package of land reform in the province, but his efforts were blocked by the Provisional Government. However, the Kornilov affair had resulted in the Provisional Government losing its control over Katerynoslav and the Makhnovists becoming the dominant force in the region. They subsequently resolved to implement land reform directly, without waiting for the Provisional Government's consent.[29] On 8 October [O.S. 25 September], the Huliaipole Congress of Soviets announced that it would be confiscating all land owned by the nobility and bringing it under common ownership, leading many landlords to flee the region.[30] Attempts to bring the region back under the control of the Provisional Government met with resistance, both from the armed anarchist detachments led by Maria Nikiforova and from a series of strike actions by sympathetic industrial workers.[31]

On 7 November 1917, the Central Council declared the autonomy of Ukraine, which brought Katerynoslav back within its borders.[32] Although the Central Council safely controlled right-bank, its new territorial claims in the left-bank were met with indifference from the more ethnically mixed population.[33] By December 1917, Eastern Ukraine had come under Soviet influence, with the First All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets establishing the Ukrainian People's Republic of Soviets in Kharkiv.[34] Unable to reconcile their differences, a civil war soon broke out between the forces of the People's Republic and the new Soviet Republic.[35]

Before the outbreak of the October Revolution, the Makhnovists had already established "soviet power" in Katerynoslav, implementing initiatives of workers' control and self-management. So when the Bolsheviks seized power under the slogan of "all power to the soviets", the Ukrainian anarchists initially supported it, while remaining critical of political and economic centralisation.[32] As the Makhnovists desired to bring the region under Soviet power, they declared themselves against the new Ukrainian nation state, establishing armed detachments to combat both the forces of the Ukrainian People's Army and the Don Cossacks.[36] An anarchist detachment led by Savelii Makhno aided in the capture of Oleksandrivsk and the reestablishment of Soviet power in the city.[37] By January 1918, Southern Ukraine had largely come under the control of the Soviet Republic, which established revolutionary committees as its local organs of power.[38] In Huliaipole, the local revolutionary committee included members of the Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionary Party and the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, alongside the anarchists.[39]

The rapid capture of territory by the Soviet Republic culminated on 8 February 1918, when the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv was captured by Mikhail Muravyov's Red Guards.[34]

War of independence (February–November 1918)

Just one day after the fall of Kyiv, the Central Council of Ukraine signed a peace treaty with the Central Powers, which invited the Imperial German Army to invade Ukraine and oust the Soviets from power.[40] The Red Guards were unable to halt the imperial advance, which within a month forced the Bolsheviks to negotiate their own peace treaty with the Central Powers, ceding control of Ukraine to the German Empire and Austria-Hungary.[41]

When the Ukrainian nationalists in Huliaipole began threatening anarchists with reprisals, local anarcho-syndicalists initiated a campaign of "revolutionary terror" against them, assassinating one nationalist leader before being forced to the negotiating table by Nestor Makhno.[42] The nationalists subsequently began planning a coup, threatening pogroms against the local Jewish community in order to bring them on side.[43] On the night of 15–16 April, the Ukrainian nationalists carried out the coup, launching a surprise attack against the anarchist "free battalion" and disarming them, before arresting leading anarcho-communists.[44] The following day, a demonstration managed to secure the release of the arrested anarchists but were unable to organize any armed defense of the town, which was soon occupied by the Austro-Hungarian Army.[45] Before the end of the month, the Ukrainian People's Republic was overthrown by the Central Powers and replaced with the Ukrainian State. Under the rule of Pavlo Skoropadskyi, the new regime began returning land to the nobility and requisitioning grain from the peasantry, which fomented popular discontent that ignited the Ukrainian War of Independence.[46]

At a conference in Taganrog, anarchist insurgents regrouped and agreed to return to Huliaipole in July 1918, in order to carry out an insurrection against the occupation forces.[47] By the time they returned to Ukraine, the country was already in revolt against the Ukrainian State, with hundreds of thousands participating in armed uprisings and rail strikes, even in the face of harsh reprisals by the occupation forces.[48] Peasant bands under various self-appointed otamans now attacked the occupation forces and eventually came to dominate the countryside; some defected to the Directorate or the Bolsheviks, but the largest portion followed either socialist revolutionary Nykyfor Hryhoriv or the anarchist flag of Makhno.[49]

On 30 September, insurgent detachments led by Nestor Makhno and Fedir Shchus linked up at Dibrivka and defeated the occupation forces in battle.[50] When the November Revolution brought World War I to an end, the occupation finally began to melt away. In right-bank Ukraine, the Ukrainian State was overthrown by the Directorate and the Ukrainian People's Republic was reestablished, while the region of Pryazovia quickly fell under the control of the Makhnovshchina.[51] On 27 November, the Makhnovshchina's capital of Huliaipole was definitively retaken by the insurgents, who reestablished the local Soviet and reorganized the town's trade unions.[52] Before long the Makhnovshchina's territory had expanded as far west as Katerynoslav, as far north as Pavlohrad, as far east as Yuzivka and as far south as the Sea of Azov.[53]

Free soviet power (November 1918 – June 1919)

The end of the imperial occupation and the fall of the Ukrainian State allowed the Makhnovshchina to shift its emphasis from military campaigns towards political concerns, transforming the movement "from a destructive peasant uprising to a social revolutionary movement".[54] In order to restart the construction of a anarchist-communist society, the Makhnovists convened a Regional Congress of Peasants, Workers and Insurgents, which would act as the supreme authority of the Makhnovshchina.[55] The Congress declared its intention to create "a society without ruling landowners, without subordinate slaves, without rich or poor", and called on workers and peasants to begin building this society themselves, "without tyrannical decrees and orders, and in defiance of tyrants and oppressors throughout the world."[56]

Under the direction of the democratically elected Military Revolutionary Council (VRS), the Makhnovshchina began to establish a new system of education, redistributed land and set up a number of agricultural cooperatives. The Ukrainian Soviet Army commander Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko reported that the Makhnovists had established a number of schools, hospitals and "children's communes", which had transformed Huliaipole into "one of the most cultured centres of Novorossiya."[57] The VRS also instituted adult educational programs and extended a number of civil liberties to the population, including freedom of speech, press and association, even allowing the Bolsheviks to agitate amongst the local populace.[58] During this period, the peasants of the Makhnovshchina implemented a system of common ownership where "land belongs to no one, and only those who work it may use it." The largest of the peasant communes was one named after the Polish communist Rosa Luxemburg, which, in May 1919, counted 285 members and 125 hectares of land.[59]

While in the Ukrainian Soviet capital of Kharkiv, the insurgent commander Viktor Bilash met with the Nabat and requested they begin producing anarchist propaganda for the Makhnovshchina, securing the passage of numerous Russian anarchist intellectuals to Ukraine,[60] including Peter Arshinov and Aron Baron. With the Nabat having moved its headquarters to Huliaipole, anarchist newspapers such as The Road to Freedom and the Makhnovist Voice quickly began circulating throughout the Makhnovist territory, widely publicizing anarchist ideas.[59] The arrival of these "urban anarchist newcomers" accelerated the development of the Makhnovshchina's anarcho-communist character, which aimed to completely restructure Ukrainian society along the lines of "free soviets".[61] These soviets, independent of all political parties, began to be set up by industrial workers, with some even receiving financing from the Makhnovists in order to make up for lost wages, which hadn't been paid due to the conditions of war.[62] The end goal of the free soviet system was to eventually convene an "all-Ukrainian labour congress", which would become the new central organ of an independent Ukraine, as a result of the Ukrainian workers' self-determination.[63]

Around this time, the Bolsheviks finally broke the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and ordered the Red Army to invade Ukraine, with Christian Rakovsky proclaiming the establishment of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in Kharkiv.[64] As the Makhnovshchina had found itself surrounded by the Ukrainian People's Republic and South Russia, the Makhnovists resolved to form an alliance with the Bolsheviks in order to maintain "soviet power" in the region, although they explicitly ruled out a political alliance and held that their pact was an exclusively military endeavor.[65] Now integrated into the Red Army, the Makhnovists secured and expanded their territory with the capture of Orikhiv, Polohy, Bakhmut, Berdiansk and Volnovakha.[66]

However, the implementation of Bolshevik rule in Ukraine was soon followed by repression. As the Bolsheviks favored the proletariat over the peasantry, on 13 April, the Ukrainian Soviet government implemented food requisitioning in order to supply its urban centers, shooting any peasants that resisted, which caused a resurgence of peasant revolts in Ukraine.[67] The Cheka also carried out its Red Terror in the areas captured by the Bolsheviks, with residents of Katerynoslav reporting arbitrary political persecution and increased economic hardship.[68] Regiments of the Red Army even began to committ robberies against the local population and carried out a number of antisemitic pogroms, as part of a rising wave of violence against Ukrainian Jews that was perpetrated by the Reds, Whites and nationalists alike.[69] In comparison to the surrounding states, the Makhnovshchina "represented a relatively peaceful model", given the ethnically diverse makeup of the Makhnovists, who severely punished acts of antisemitism.[70]

The Bolsheviks' implementation of bureaucratic collectivism and their authoritarianism brought them into opposition with the Makhnovshchina, which still upheld soviet democracy and libertarian socialism.[71] In May 1919, tensions between the two were exacerbated when Nykyfor Hryhoriv led an anti-Bolshevik uprising in right-bank Ukraine, during which his green army carried out a series of antisemitic pogroms and anti-communist purges.[72] The Makhnovists decided to take up arms against Hryhoriv and maintain their alliance with the Bolsheviks, hoping that talks between the two parties would result in the official extension of autonomy to the territory of the Makhnovshchina.[73] But tensions between the two parties only increased with time, eventually resulting in the Makhnovists completely breaking from their Bolshevik commanders.[74]

Retreat to the west (June–October 1919)

When the Military Revolutionary Council called an extraordinary Regional Congress, it was considered to be an act of treason by the Bolshevik government, which ordered the Congress be prohibited and that any of its participants be executed by firing squad.[75] The Bolsheviks subsequently attacked the Makhnovshchina, killing a number of the Makhnovist general staff and forcing the insurgents to flee, which began a period of guerrilla warfare in the region.[76] By June 1919, the autonomy of the Makhnovshchina had been suppressed by the successive Red Terror and White Terror.[77]

It was at this time that the White movement broke through the Soviet lines in Donbas, with the Kuban Cossacks under Andrei Shkuro leading an attack against Huliaipole, capturing the town from the Makhnovists.[78] As the Red Army had also declared war against the Makhnovshchina, labelling Huliaipole as a "paradise on earth for cowards and good-for-nothings," the local insurgents were left without Bolshevik support and many peasants were forced to defend the town themselves, armed only with farming tools and a few rifles.[79] The Cossacks massacred the peasant rebels and raped 800 of the town's women, before restoring the property rights of the former landowners, causing a mass exodus of the town's peasantry.[80]

The Makhnovists fled to right-bank Ukraine and linked up with Nykyfor Hryhoriv's green army.[81] But after revelations of the otaman having committed antisemitic pogroms, the Makhnovists assassinated Hryhoriv and began rebuilding their forces to take on the Whites.[82] By September 1919, the Makhnovshchina had been pushed back as far as Uman, the last stronghold of the Ukrainian People's Republic. In order for their wounded to be tended to, the Makhnovists formed a temporary alliance with the Directorate, before turning back around and leading an attack against the General Command of the Armed Forces of South Russia.[83] After the Battle of Peregonovka, the tide turned against the Whites as the Makhnovists pushed them back into Katerynoslav, which was brought back under the control of the Makhnovshchina on 11 November 1919.[84]

Apex (October 1919 – January 1920)

The Makhnovist advance brought with it a second period of reconstruction, during which a system of libertarian socialism was once again implemented throughout the territory of the Makhnovshchina, with all enterprises being directly transferred to workers' control.[86] Wherever the insurgents captured, the locals were invited to elect their own trade union delegates and Soviets, which would then convoke a regional congress that would form the decision-making body for the region.[87]

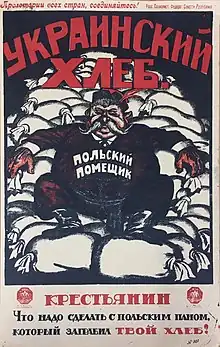

Regional workers' conferences were subsequently held in Oleksandrivsk between 27 October and 2 November, bringing together 180 peasant delegates, 20 worker delegates and 100 delegates from left-wing political organizations and insurgent units.[88] Volin, the chair of the congress, proposed that they adopt the anarchist thesis of establishing "free soviets", outside of political party control, throughout the Makhnovist territory. This proposal was objected to by 11 delegates from the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionary Party, who still desired the reestablishment of the Constituent Assembly and walked out of the congress.[89] Further objections were made by a Bolshevik delegate, who rejected calls for anarchy.[90]

By December 1919, the Makhnovshchina was struck by an outbreak of epidemic typhus, which incapacitated the Makhnovist forces, allowing the White movement to briefly recapture Katerynoslav and the Red Army to invade the region.[91]

Red Terror (January–October 1920)

By the end of January 1920, the territory of the Makhnovshchina had been overrun by the Red Army.[92] The Cheka set about disarming the local populace, taking villagers hostage while their troops set about searching homes, killing the hostages if they found any unreported weaponry.[93] Petro Grigorenko would later state that "there was no end of bloodshed", drawing attention to reports of one massacre in the Makhnovist town of Novospasivka, where the Cheka had "shot down one in every two able-bodied men". In what Alexandre Skirda described as an act of "outright genocide", an estimated 200,000 Ukrainian peasants were killed during the Red Terror.[94]

The Bolshevik government implemented war communism in Ukraine, introducing a strict system of rationing and food requisitioning, which confiscated agricultural produce and livestock from the peasantry, and even forbade them from fishing, hunting or collecting lumber.[95] The attacks against the Ukrainian peasantry were justified under the policy of Dekulakization, despite the fact that, by this point in time, only 0.5% of the peasantry owned more than 10 hectares of land.[96] The sovkhozes also collapsed, with the number of state-owned farms halving and their land area reducing to a third, over the course of 1920. Even the soviet historian Mikhail Kubanin noted that to most of the Ukrainian peasantry: "the Soviet economy was a new and abhorrent form of rule [...] which in reality had merely set the State in the place of the former big landowner." The implementation of war communism thus resulted in a resurgence of peasant revolts. Before the fall of 1920, over 1,000 Bolshevik victualers had been killed by the Ukrainian peasantry.[97]

The Makhnovists themselves began to wage a campaign of guerrilla warfare against the Bolsheviks, launching a series of attacks against small Red detachments and infrastructure. In the areas which they captured, they abolished war communism and redistributed requisitioned food back to the peasantry, forcing many Bolsheviks in the area back underground.[92]

Starobilsk peace (October–November 1920)

Following a successful White offensive into Northern Taurida, the Makhnovists and Bolsheviks once again formed an alliance.[98] The conditions of the Political Agreement between the two parties stated that: all anarchist political prisoners were to be released and political repression against the anarchist movement ceased; anarchists were to be extended a number of civil liberties including freedom of speech, freedom of the press and freedom of association, excluding any anti-Soviet agitation; and anarchists were to be allowed to freely participate in elections to the Soviets and the upcoming Fifth All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets.[99]

A fourth clause of the political pact would have extended full autonomy to the Makhnovshchina, allowing them to establish institutions of workers' self-management and self-government in south-eastern Ukraine, under a federative agreement with the Ukrainian SSR.[100] But this clause was disputed by the Bolshevik delegation,[101] who feared this would limit their access to the Ukrainian rail network and turn the Makhnovshchina into a "magnet for all dissidents and refugees from Bolshevik-held territory."[10] The issue was postponed indefinitely.[102]

But now that Ukrainian anarchists were once again free to operate, they quickly pushed the Russian Army out of Huliaipole and Makhnovshchina control was once again reestablished.[103] Having once again regained control of their home territory, the Makhnovists drew up a program to reorganize the economy and society along anarchist lines.[104] By mid-November, the free soviets were being reconstituted, libertarian schools were established and theater shows were put on daily.[105] According to the Polish anarchist Casimir Teslar, the scars of war ran deep throughout the region. He reported seeing abandoned trenches, demolished houses and a strong presence of insurgent detachments, detailing that even the local children were playing wargames based on recent events.[106]

Defeat (November 1920 – August 1921)

After Semen Karetnyk's detachment assisted in the siege of Perekop, which had forced the Army of Wrangel to evacuate from Crimea, the Bolsheviks turned against the Makhnovshchina on 26 November 1920.[107] Many prominent Ukrainian anarchists were arrested and shot, while the Makhnovist capital of Huliaipole was itself captured by the Red Army.[108] The Cheka also intensified the Red Terror in Ukraine, ordering the Southern Front to search and disarm peasants, and to shoot any that resisted. They also purged the district of any suspected Makhnovists, arresting the entire revolutionary committee in Polohy and executing a number of its members for allegedly collaborating with the Makhnovists during the Ukrainian War of Independence in 1918.[109] In the place of the liquidated free soviets, the Bolsheviks established committees of Poor Peasants to take over local administration of Ukrainian villages.[110]

Hoping to keep the Makhnovshchina safe from reprisals, the Insurgent Army retreated into right-bank Ukraine then moved on north, passing through Poltava, Chernihiv and Belgorod, before returning to Katerynoslav in February 1921. Once again on their home turf, they aimed to spread the Makhnovshchina to new territories and to establish reliable insurgent bases throughout Ukraine.[111] However, the Bolshevik government's implementation of the New Economic Policy resulted in many Ukrainian peasants losing their will to fight, leading to a series of military defeats and the dwindling of insurgent forces.[112] On 28 August 1921, Nestor Makhno's forces fled to Romania, leaving the country entirely under control of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.[113]

Politics

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchist communism |

|---|

|

The political system established by the Makhnovshchina was variously described as a "people's commune" or an "anarchist republic",[114] one based on the theories of anarcho-communism and built on a network of trade unions, factory committees, peasant committees and popular assemblies. The assemblies were used by the local citizens as a form of referendums, where decisions were made through direct democracy, and became the basis for civil law.[25] The vast majority of the Makhnovshchina's decisions were made independently, through a system of local self-governance at the village and district level. Networks of "free soviets" acted as institutions of participatory democracy, where issues would be discussed and dealt with directly.[115]

Local self-government

The free soviets were conceived of as the basic form of organization in the Makhnovshchina. These soviets acted independently from any Central Authority, excluding all political parties from participation, and met to self-manage the activities of workers and peasants through participatory democracy.[116] The soviets acted as the local organs of self-governance and federated together up to the regional and national levels, resulting in the relatively horizontal organization of the soviets. However, the conditions of the war meant that the Soviet model could only be implemented at scale during "periods of relative peace and territorial stability", as the populace was largely concerned with securing food or staying safe from the advancing armies.[117]

Regional congress and executive

The Regional Congress of Peasants, Workers and Insurgents represented the "highest form of democratic authority" within the political system of the Makhnovshchina.[118] They brought together delegates from the region's peasantry, industrial workers and insurgent soldiers, which would discuss the issues at hand and take their decisions back with them to local popular assemblies.[119] Four Congresses were held over the course of 1919, while one was banned by the Bolsheviks and another was unable to convene due to renewed conflict with the Red Army.[120]

The Military Revolutionary Council (VRS) acted as the executive in the interim between sittings of the Regional Congresses.[121] Its powers covered both military and civil matters in the region, although it was also subject to instant recall at the will of the Regional Congress[122] and its activities were limited to those explicitly outlined by the Congresses themselves.[123] At each Regional Congress, the VRS was to provide detailed reports of its activities and subjected itself to reorganization.[124] When it came to the decisions of local soviets and assemblies, the VRS presented itself as a solely advisory board, with no power over the local bodies of self-government.[115]

Armed forces

The Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine (RIAU), commanded by Bat'ko Nestor Makhno, constituted the principal armed force of the Makhnovshchina. Composed largely of peasant partisans and generally supported by the wider peasantry, the RIAU was able to capture large amounts of territory throughout southern Ukraine.[63] Within this area, the RIAU's Draft Declaration stated that its aim was to "serve and protect" the social revolution in Ukraine, but also that it would not impose its own ideals upon the Ukrainian people.[125] Nominally overseen by the civilian VRS,[126] the RIAU played a purely military role, with Makhno himself functioning as little more than a military strategist and advisor.[127] According to the Soviet historian Mikhail Kubanin, "neither the overall command of the army nor Makhno himself truly ran the movement; they merely reflected the aspirations of the mass, acting as its ideological and technical agents."[128]

Civil liberties

Civil liberties were first introduced to southern and eastern Ukraine following the February Revolution, but were suspended with the outbreak of the Ukrainian War of Independence, when the territory fell under the sequential control of the Ukrainian State, Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and South Russia. Following the defeat of the White movement in October 1919 and the subsequent extension of the Makhnovshchina throughout the area, freedom of speech, freedom of the press and freedom of association were all reintroduced.[129]

The implementation of freedom of the press resulted in the appearance of a number of newspapers in the territory, including the official organs of several political organizations. These included the Socialist Revolutionary Party's People's Power (Narodovlastie), the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries' Banner of Revolt (Znamya Vosstanya), the Bolsheviks' Star (Zvezda), the Mensheviks' Workers' Gazette (Rabochaia Gazeta), the Ukrainian Anarchist Confederation's Nabat and the Insurgent Army's own Road to Freedom.[129]

Economy

Workers and peasants of Ukraine saw the October Revolution, which had promised "Factories to the Workers; Land to the Peasants!", as the beginning of workers' control of the industrial economy and land redistribution to the peasantry.[130] In the territory controlled by the Makhnovshchina, a system of market socialism was implemented, to the particular benefit of the peasantry and workers that produced consumer goods, while social welfare was introduced through the redistribution of income and wealth.[86]

Agricultural communes

For the first year of the Russian Revolution, an energized Ukrainian peasantry carried out a campaign of expropriations against the pomeshchiks and kulaks, redistributing land to those that worked it and creating an agrarian socialist economy.[131] In the wake of the Kornilov affair, the revolutionary defense committee in Huliaipole sanctioned the disarmament and dispossession of the local bourgeoisie, bringing all private enterprise in the area under workers' control.[132] Peasants took control of the farms they worked and large estates were collectivized, creating agrarian communes that were settled by previously landless peasant families and individuals, with each commune counting around 200 members.[133]

The first commune, named after Rosa Luxemburg, was highly successful. Though only a few members actually considered themselves anarchists, the peasants operated the communes on the basis of full social equality, including gender equality. They accepted Kropotkin's principle of mutual aid ("from each according to their ability, to each according to their need") as their fundamental tenet.[134] Land was held in common, with shared meals also being eaten in communal kitchens, though members who wished to cook separately or to take food from the kitchen and eat it in their own quarters were allowed to do so. The work was collectively self-managed, with work programs being voluntarily agreed upon through consensus decision-making at general assemblies, and those who were unable to work could notify their neighbors in order for a replacement to be found.[135] Many commune members considered communal life to be the "highest form of social justice", with some former landowners even voluntarily adopting the new lifestyle.[136]

The father of Victor Kravchenko was one of the promoters of a commune called the "Tocsin", which counted 100 families on an estate made up of 200 hectares of wheat fields and orchards. The estate had been divided up and supplied by the local soviet, with many former industrial workers flocking to the new commune due to the promise of "well-being for everybody", while others were driven to communal life by their own ideological commitments. Some peasants even made fun of the urban communists that had joined the commune, although Kravchenko insisted that "such teasing was without malice", as the peasants still undertook to help the unskilled industrial laborers.[137] However, this commune eventually dissolved, "with commune workers quitting one after another".[138]

Industry

While the Makhnovshchina was a primarily agrarian society, efforts were also made to organize the industrial economies in the cities which the Makhnovists briefly occupied, despite the pervasive lack of understanding that the (largely peasant) insurgents had for large-scale industry.[139] Upon the occupation of cities, the Makhnovists organized workers' conferences with the intention of restarting production under a system of workers' self-management. When urban workers asked for the payment of their wages, still in arrears following the end of the White occupation, the Makhnovists responded by proposing they extract payment directly from their customers, albeit exempting the Insurgent Army from such payment.[140]

Railroad workers in Oleksandrivsk took the first steps in organising a self-managed economy in 1919. They formed a committee charged with organizing the railway network of the region, establishing a detailed plan for the movement of trains, the transport of passengers, etc. Soviets were soon formed to coordinate factories and other enterprises across Ukraine.[141]

In Katerynoslav, the local anarcho-syndicalist movement took the reins on bringing the city's industrial economy under social ownership. Collective agreements were won at a tobacco factory and the city's bakeries were brought under workers' control, with a number of anarcho-syndicalist bakers drawing up plans to ensure food security for the local population.[142]

Many industrial workers ended up becoming disillusioned with the Makhnovshchina and instead supported the program of the Mensheviks.[86] At one Regional Congress of Peasants, Workers and Insurgents, Menshevik trade union delegates were denounced as "counter-revolutionaries" for speaking out against the Makhnovist platform of free soviets and subsequently walked out of the congress.[143]

Money

The Makhnovshchina came up against difficulties concerning the issue of money, as its largely peasant base could easily go without money through subsistence farming, while urban workers still needed to buy their own food. When the direct exchange of goods was not possible, the Makhnovshchina largely continued to use money, but planned to build a moneyless system following the Russian Civil War.[144]

Early on, barter had been a popular means of exchange, with the Huliaipole Soviet even establishing links with textile factories in industrial centers such as Moscow. The Soviet procured wagon loads of cloth in exchange for grain, directly exchanged in quantities determined by the needs of both parties.[145] However, this barter economy was frustrated by the newly established Council of People's Commissars, controlled by the Bolsheviks and Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, which demanded an end to the independent barter economy and called for it to be brought under the control of the government.[138]

Although the anarchists of the Makhnovshchina preferred a barter economy, they recognized that the working poor were still in need of money and permitted the use of any currencies, including the Imperial ruble, Soviet ruble and Ukrainian karbovanets.[146] One account even suggests that the Makhnovists printed their own money (the Makhnovist ruble), which stated on its reverse that "no-one would be prosecuted for forging it".[147]

The regional congresses imposed levies against the local bourgeoisie and banks, extracting about 40 million rubles from the bourgeoisie and seizing 100 million rubles from the banks.[148] An extensive wealth redistribution campaign was subsequently implemented, in which the poor were able to apply for material assistance from the Military Revolutionary Council. One resident of Katerynoslav reported that thousands of people queued up on a daily basis for the redistribution packages, which they would receive in varying amounts depending on the assessment of their needs, with applicants being awarded up to thousands of rubles.[149] Redistribution measures reportedly continued up until the final days of Makhnovshchina control, with an estimate 3–10 million rubles being distributed to the population of Katerynoslav alone.[150]

The Makhnovists' unfamiliarity with monetary economics led to high rates of inflation, while the changing military situation resulted in wild fluctuations of currency value, with Soviet rubles appreciating in value as the Red Army advanced into Ukraine.[151] They also neglected to impose price controls, which caused the price of bread to rise by 25% during Makhnovshchina control.[150]

Demographics

The territory of the Makhnovshchina was mainly spread across the regions of Pryazovia and Zaporizhzhia.[152] At its height, the population of the Makhnovshchina was roughly 7.5 million people, spread across 75,000 km2 of territory. At its greatest extent, the territory covered five provinces, including the entirety of Katerynoslav, as well as the northern part of Taurida, the eastern part of Kherson and the southern parts of Poltava and Kharkiv.[4]

Nationalities and ethnic groups

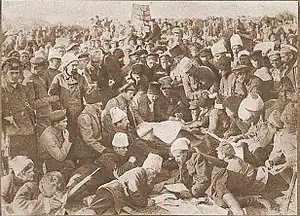

Following the end of World War I, the existing empires and multinational states were collapsing, leading to a rise of the nation state as the dominant polity.[153] While a number of ethnic minorities of the former Russian Empire began to break off and form their own independent states, such as the Ukrainian People's Republic, the territory of the Makhnovshchina was notably multicultural and resisted the rising wave of Ukrainian nationalism.[5] According to Peter Arshinov, while 90% of the Makhnovshchina was made up of Ukrainians, 6–8% was made up of Russians and the remainder consisted of Greek and Jewish communities. There also existed small minorities of Armenians, Bulgarians, Georgians, Germans and Serbs.[154]

As such, the Makhnovshchina sought "to deconstruct the entire state-based national paradigm, and build local socio-economic relations from the bottom up on anarchist principles."[155] In February 1919, the Second Regional Congress of Peasants, Workers and Insurgents passed a resolution denouncing nationalism and called on "the workers and peasants of every land and all nationalities" to join together in a social revolution to overthrow the state and capitalism.[156] In October 1919, the Draft Declaration adopted by the Military Revolutionary Council hoped to put an end to the "domination of one nationality over others" through the introduction of free soviets.[157] Although it proclaimed "the right of the Ukrainian people (and every other nation) to self-determination", it also considered nationalism to be "profoundly bourgeois and negative" and called instead for the "union of nationalities" under socialism, which it believed would "lead to development of the culture peculiar to each nationality."[158]

The Makhnovists specifically railed against antisemitism, which they considered to be a "bequest" of the Tsarist autocracy,[159] and the Military Revolutionary Council even went so far as to declare a "war on anti-Semitism".[160] Instances of antisemitic violence were notably much less common in the territory of the Makhnovshchina than they were in right-bank Ukraine,[161] with any cases of antisemitism being punished severely by the Makhnovists.[162] After one documented instance of an antisemitic pogrom taking place in Makhnovist territory, the insurgents responsible were executed by firing squad and weapons were redistributed to the local Jewish communities for their own protection.[163] Many of the Makhnovshchina's most influential figures also came from a Jewish background, including a number of Nabat's leading members: Aron Baron, Mark Mratchny and Volin.[164]

In contrast to the Makhnovist hostility to antisemitism, anti-German sentiment was allowed to proliferate throughout the ranks of the Makhnovshchina,[165] as the result of long and deeply-held resentments between the native Ukrainian peasantry and German Mennonite colonists.[166] Following the battle of Dibrivka and the destruction of Velykomykhailivka by the Austro-Hungarian Army and local German collaborators, the Insurgent Army carried out a campaign of reprisals against Mennonite colonists in southern Ukraine.[167] Anti-Mennonite repression intensified when the Selbstschutz formed an alliance with the White movement, leading to a number of insurgent raids against Mennonite settlements.[168] Violence against the Mennonites reached its apex following the battle of Peregonovka, when the insurgents rapidly occupied most of southern and eastern Ukraine, bringing numerous Mennonite colonies under their occupation.[169] Throughout late-1919, hundreds of Mennonites were murdered in a series of massacres committed by the insurgent forces, the most infamous of which was the Eichenfeld massacre.[170]

Language

The different language policies of the various regimes that occupied Ukraine during the war of independence led to a number of shifts in the use of language throughout Zaporizhzhia. The Ukrainian State had prioritized the use of the Ukrainian language, enforcing its use in education,[171] and following the region's occupation by the Volunteer Army in June 1919, Vladimir May-Mayevsky banned the use of the Ukrainian language in schools throughout South Russia, instead enforcing the use of the Russian language.[172] In reaction to the linguistic restrictions enforced by the various preceding governments, after the Makhnovist victory over the White movement at the Battle of Peregonovka, the Makhnovshchina's "Cultural Enlightenment Section" declared that people were to be educated in whichever language was used by the local population, to be decided on voluntarily by the people themselves.[173] In the majority of villages and towns in the Makhnovist territory, this meant a return to the use of the Ukrainian language[174] and an end to the privileged status of the Russian language.[175]

Nevertheless, the Russian language had a notable prevalence in left-bank Ukraine.[176] Since the 1905 Revolution, the Ukrainian anarchist movement's publications had largely been in the Russian language,[177] and the predominance of the Russian language in anarchist literature continued following the emigration of Russian anarchists to the territory of the Makhnovshchina.[178] But driven by a small number of Ukrainian intellectuals, led by Halyna Kuzmenko, the Makhnovshchina increasingly started to use the Ukrainian language in both its propaganda and educational activities, leading to a notable Ukrainization of the Makhnovist movement.[179] In late 1919, the Makhnovists began to publish a Ukrainian language edition of The Road to Freedom (Ukrainian: Шлях до Волі) in Katerynoslav, and set up a new publication called Anarchist Rebel (Ukrainian: Анархіст-Повстанець) in Poltava. But this would prove to be the extent of the Makhnovist movement's Ukrainian language publications, as they still lacked editors and proofreaders that were competent in the written Ukrainian language, and sometimes had no access to printing presses that carried the Ukrainian alphabet.[180]

Education and culture

During the 1917 Revolution, members of the Huliaipole Anarchist Group first proposed the creation of a new system of education,[181] inspired by the work of the Catalan pedagogue Francesc Ferrer.[182] One group member, Abram Budanov, took the initiative to establish a Cultural-Educational section for the nascent Makhnovist movement. This section would publish pamphlets and hold meetings, but would also organise the establishment of educational institutions, theatre productions and live music shows.[183] With the outbreak of the war, the Cultural-Educational Section was brought under the oversight of the Military Revolutionary Council.[184] At the beginning of 1919, a number of Russian anarchist intellectuals emigrated to southern Ukraine, where they began work for the Cultural-Educational section.[185] Peter Arshinov, who had educated Nestor Makhno during their time in prison, became the section's Chairman and edited the insurgent newspaper The Road to Freedom.[186] In the summer of 1919, he was joined members of the Nabat,[183] including Volin and Aron Baron.[187] Volin, who had briefly worked in the Department of Education of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic,[188] oversaw the drawing up of the Draft Declaration, which declared the need for cultural and educational institutions to be outside of state control, instead proposing they be established as voluntary associations.[189]

The Makhnovshchina's education system was spearheaded by Halyna Kuzmenko, a Ukrainian pedagogue and former primary school teacher.[190] From as early as the February Revolution, teachers were already engaged in setting up schools in Huliaipole,[175] with three secondary schools being established by 1919, despite the conditions of the war.[191] Adult education was also carried out, with a focus on political agitation,[192] by educational workers within the Insurgent Army itself.[193] But by the time that the armistice with the Bolsheviks was promulgated in October 1920, most of the region's teachers had fled and few schools were still open. Driven by the ideology of the Ferrer movement, the Makhnovshchina responded with plans to open new workers' schools, supported by their local communities, which would educate both children and adults.[194] The Nabat member Levandovski proposed the establishment of an anarchist university in Kharkiv, which would have cost the Huliaipole Soviet some 10 million rubles.[195] But Nestor Makhno himself rejected the idea, as he considered educational institutions to be most needed in rural areas and believed that the instinct to establish such a university in a large city like Kharkiv was indicative of centralism.[196]

Meanwhile, the cultural section travelled with the Insurgent Army, publishing flyers and issues of The Voice of the Free Insurgent using a mobile printing press. When the Insurgent Army halted, the cultural section provided entertainment and organised conferences, where they advocated for free soviets.[197] As part of their cultural activities, Makhnovist men and women staged daily amateur theatre shows, during which they dramatised the region's recent history and the story of the Insurgent Army.[198] The theatre section itself had a number of units that specialised in different types of productions, whether musical, dramatic, operatic or satirical.[190] The Cultural-Educational Section often used entertainment as a way to raise money for wounded insurgents, holding plays and Dutch auctions in a number of southern Ukrainian towns.[175] Music also played an important role in the Makhnovshchina, with musical ensembles often accompanying meetings and the harmonica becoming a popular instrument among the insurgents.[191] Makhnovist musicians played a number of original songs, including their own version of the popular folk song Yablochko, which depicted insurgents triumphing over the forces of Anton Denikin's White movement.[175]

Following the siege of Perekop and the renewal of Bolshevik attacks against the Makhnovshchina, the remains of the Makhnovist cultural and educational programs were finally destroyed.[199] Bolshevik reforms to education included the scrapping of the final year of secondary education and the requirement that all teachers seek election. Political commissars and Bolshevik cells were established in all schools, in order to remove teachers that contradicted the party line.[200]

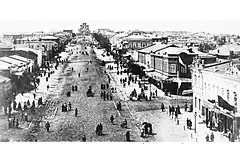

Urbanisation

While the territory of the Makhnovshchina was a predominantly rural, it also included a number of large cities, with the Insurgent Army capturing several following the Battle of Peregonovka.[201] Its capital city was Nestor Makhno's relatively small hometown of Huliaipole, which was nicknamed "Makhnograd" by the Bolsheviks.[4]

| Rank | Province | Pop. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Katerynoslav  Yelisavetgrad |

1 | Katerynoslav | Katerynoslav | 189,000 (1920) |  Oleksandrivsk  Mariupol | ||||

| 2 | Yelisavetgrad | Kherson | 65,000 (1926) | ||||||

| 3 | Oleksandrivsk | Katerynoslav | 58,517 (1917) | ||||||

| 4 | Mariupol | Katerynoslav | 30,000 (1921) | ||||||

| 5 | Berdiansk | Taurida | 26,400 (1926) | ||||||

| 6 | Huliaipole | Katerynoslav | 25,000 (1917) | ||||||

| 7 | Melitopol | Taurida | 22,022 (1912) | ||||||

| 8 | Nikopol | Taurida | 21,282 (1897) | ||||||

| 9 | Kryvyi Rih | Kherson | 19,000 (1923) | ||||||

| 10 | Polohy | Katerynoslav | 16,490 (1959) | ||||||

See also

References

Citations

- Darch 2020, p. 234; Malet 1982, p. 9, 223; Peters 1970, pp. 7–8; Shubin 2010, p. 147; Skirda 2004, p. 3; Sysyn 1977, p. 277.

- Darch 2020, pp. 9, 107; Skirda 2004, pp. 332–333.

- Shubin 2010, p. 166; Skirda 2004, p. 2.

- Skirda 2004, p. 2.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 149–150.

- Skirda 2004, p. 344.

- Darch 2020, p. 39; Skirda 2004, p. 154.

- Skirda 2004, p. 104.

- Darch 2020, p. 112; Malet 1982, p. 123.

- Malet 1982, p. 66.

- Skirda 2004, p. 115.

- Malet 1982, p. 38.

- Darch 2020, p. 108.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 147–148; Skirda 2004, pp. 8–16.

- Shubin 2010, p. 148.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 148–149.

- Shubin 2010, p. 149.

- Malet 1982, p. 169; Shubin 2010, p. 150.

- Avrich 1971, pp. 17–18; Shubin 2010, p. 150.

- Avrich 1971, pp. 42–43; Shubin 2010, p. 150.

- Avrich 1971, p. 209; Shubin 2010, pp. 150–151; Skirda 2004, pp. 20–24.

- Avrich 1971, p. 209; Shubin 2010, pp. 151–152; Skirda 2004, pp. 24–29.

- Darch 2020, p. 10.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 152–153.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 153–154.

- Malet 1982, pp. 3–4.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 154–155.

- Shubin 2010, p. 154.

- Shubin 2010, p. 155.

- Malet 1982, p. 5; Shubin 2010, p. 155.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 155–157.

- Shubin 2010, p. 157.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 158–159.

- Shubin 2010, p. 159.

- Malet 1982, pp. 5–6; Shubin 2010, p. 159.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 157–158.

- Malet 1982, pp. 6–7.

- Malet 1982, p. 7.

- Malet 1982, pp. 7–8.

- Malet 1982, p. 8; Shubin 2010, p. 160.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 160–161.

- Shubin 2010, p. 161.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 161–162.

- Shubin 2010, p. 162.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 162–163.

- Shubin 2010, p. 163.

- Malet 1982, p. 9.

- Malet 1982, p. 13.

- Magocsi 1996, pp. 498–99; Subtelny 1988, p. 360.

- Darch 2020, pp. 32–33; Footman 1961, pp. 260–262; Malet 1982, pp. 15–19; Palij 1976, pp. 96–103; Peters 1970, pp. 41–42; Shubin 2010, pp. 163–164; Skirda 2004, pp. 60–64.

- Darch 2020, pp. 33–34; Malet 1982, pp. 19–20; Peters 1970, p. 42; Shubin 2010, pp. 164–165; Skirda 2004, p. 67.

- Malet 1982, p. 19.

- Malet 1982, p. 20.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 164–165.

- Darch 2020, p. 40; Footman 1961, p. 266; Shubin 2010, p. 165; Skirda 2004, p. 299.

- Shubin 2010, p. 165.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 165–167.

- Shubin 2010, p. 167.

- Skirda 2004, p. 86.

- Skirda 2004, p. 82.

- Shubin 2010, p. 168.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 168–169.

- Shubin 2010, p. 169.

- Skirda 2004, p. 80.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 169–170.

- Shubin 2010, p. 170.

- Shubin 2010, p. 173; Skirda 2004, pp. 83–84.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 84–85.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 170–172.

- Shubin 2010, p. 172.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 85–86.

- Shubin 2010, p. 174.

- Shubin 2010, p. 176.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 176–178.

- Darch 2020, p. 60; Malet 1982, p. 38; Skirda 2004, p. 111–116.

- Shubin 2010, p. 178.

- Darch 2020, p. 61; Malet 1982, pp. 38–40; Skirda 2004, pp. 119–120.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 117–118.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 119–120.

- Skirda 2004, p. 124.

- Shubin 2010, p. 179.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 180–181.

- Shubin 2010, p. 181.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 181–182; Skirda 2004, p. 152.

- Volin 1947, Photographs - Map of the Makhnovist region and movement.

- Shubin 2010, p. 182.

- Skirda 2004, p. 153.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 153–154.

- Skirda 2004, p. 154.

- Skirda 2004, p. 155.

- Shubin 2010, p. 183.

- Shubin 2010, p. 184.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 168–169.

- Skirda 2004, p. 169.

- Skirda 2004, p. 173.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 173–174.

- Skirda 2004, p. 174.

- Shubin 2010, p. 184; Skirda 2004, pp. 194–196.

- Darch 2020, p. 111; Footman 1961, p. 295; Malet 1982, p. 65; Peters 1970, pp. 126–127; Skirda 2004, p. 196.

- Darch 2020, p. 111; Footman 1961, pp. 295–296; Malet 1982, pp. 65–66; Skirda 2004, p. 197.

- Darch 2020, p. 111; Footman 1961, pp. 295–296; Malet 1982, p. 65.

- Darch 2020, p. 111; Footman 1961, pp. 295–296.

- Malet 1982, pp. 66–67; Shubin 2010, pp. 184–185; Skirda 2004, pp. 223–225.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 232–233.

- Skirda 2004, p. 233.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 233–234.

- Malet 1982, pp. 67–71; Shubin 2010, pp. 185–186.

- Malet 1982, pp. 71–72; Shubin 2010, p. 186.

- Shubin 2010, p. 187.

- Malet 1982, p. 72.

- Shubin 2010, pp. 187–188.

- Darch 2020, pp. 119–120; Shubin 2010, p. 188.

- Shubin 2010, p. 188.

- Skirda 2004, p. 92.

- Skirda 2004, p. 333.

- Malet 1982, p. 107.

- Malet 1982, pp. 107–108.

- Darch 2020, p. 40; Skirda 2004, p. 299.

- Darch 2020, p. 40.

- Malet 1982, p. 108.

- Malet 1982, p. 27; Skirda 2004, pp. 87, 299–300.

- Skirda 2004, p. 87.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 93–94.

- Skirda 2004, p. 112.

- Skirda 2004, p. 371.

- Malet 1982, p. 27; Skirda 2004, p. 314.

- Skirda 2004, p. 34.

- Skirda 2004, p. 314.

- Skirda 2004, p. 159.

- Arshinov 1974, p. 22.

- Malet 1982, pp. 117–119; Shubin 2010, pp. 154–155.

- Skirda 2004, p. 37.

- Malet 1982, pp. 120–121; Skirda 2004, p. 37.

- Volin 1947.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 37–38.

- Skirda 2004, p. 38.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 38–39.

- Skirda 2004, p. 39.

- Malet 1982, pp. 122–123.

- Malet 1982, p. 123.

- Arshinov 1974, pp. 85–87.

- Malet 1982, p. 124.

- Malet 1982, pp. 109, 123–124; Skirda 2004, pp. 154.

- Malet 1982, p. 112.

- Malet 1982, pp. 119–120; Skirda 2004, p. 39.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 158–159.

- Darch 2020, p. 101; Malet 1982, p. 112.

- Skirda 2004, p. 157.

- Malet 1982, p. 113; Skirda 2004, pp. 157–158.

- Malet 1982, p. 113.

- Malet 1982, pp. 112–113.

- Shubin 2010, p. 147.

- Darch 2020, p. 147.

- Skirda 2004, p. 338.

- Darch 2020, pp. 147–148.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 367–368.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 371–372.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 377–378.

- Skirda 2004, p. 367.

- Skirda 2004, p. 340.

- Malet 1982, p. 169; Shubin 2010, p. 150; Skirda 2004, p. 339.

- Avrich 1971, p. 216; Footman 1961, p. 284; Malet 1982, pp. 170–171; Shubin 2010, p. 172.

- Malet 1982, p. 170; Skirda 2004, p. 338.

- Avrich 1971, pp. 215–216; Skirda 2004, p. 339.

- Patterson 2020, p. 142.

- Darch 2020, pp. 29–30; Patterson 2020, pp. 140–141.

- Darch 2020, pp. 32–33; Malet 1982, p. 17; Palij 1976, pp. 102–103; Patterson 2020, pp. 56–57; Shubin 2010, pp. 163–164; Skirda 2004, pp. 63–64.

- Patterson 2020, pp. 23, 60–64.

- Patterson 2020, p. 69.

- Darch 2020, p. 29; Patterson 2020, pp. 62–63.

- Peters 1970, p. 47.

- Skirda 2004, p. 147.

- Sysyn 1977, pp. 288–289.

- Malet 1982, p. 143.

- Malet 1982, p. 178.

- Darch 2020, p. 151.

- Sysyn 1977, pp. 280–281.

- Sysyn 1977, pp. 298–299.

- Sysyn 1977, pp. 289–290.

- Darch 2020, pp. 87–88.

- Darch 2020, pp. 17–18; Malet 1982, p. 165.

- Avrich 1971, p. 215; Darch 2020, pp. 17–18; Malet 1982, p. 165.

- Malet 1982, p. 175.

- Darch 2020, pp. 70–71; Malet 1982, p. 111; Skirda 2004, p. 186.

- Malet 1982, p. 166.

- Avrich 1971, p. 215; Patterson 2020, pp. 26–28; Skirda 2004, p. 323.

- Avrich 1971, p. 215; Malet 1982, p. 172; Skirda 2004, p. 339.

- Avrich 1971, p. 199; Darch 2020, pp. 141–142.

- Skirda 2004, p. 378.

- Darch 2020, p. 102.

- Darch 2020, p. 102; Malet 1982, p. 178.

- Darch 2020, p. 52.

- Darch 2020, p. 69; Peters 1970, pp. 60–61.

- Malet 1982, pp. 178–179.

- Malet 1982, p. 179; Skirda 2004, p. 331.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 331–332.

- Skirda 2004, pp. 181–182.

- Avrich 1971, p. 215; Malet 1982, p. 178; Skirda 2004, p. 233.

- Malet 1982, p. 179.

- Skirda 2004, p. 85.

- Skirda 2004, p. 137.

Sources

- Arshinov, Peter (1974) [1923]. History of the Makhnovist Movement. Detroit: Black & Red. OCLC 579425248.

- Avrich, Paul (1971) [1967]. The Russian Anarchists. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00766-7. OCLC 1154930946.

- Darch, Colin (2020). Nestor Makhno and Rural Anarchism in Ukraine, 1917–21. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0745338880. OCLC 1225942343.

- Eichenbaum, Vsevolod Mikhailovich (1955) [1947]. The Unknown Revolution. Translated by Cantine, Holley. New York: Libertarian Book Club. ISBN 0919618251. OCLC 792898216.

- Footman, David (1961). "Makhno". Civil War in Russia. Praeger Publications in Russian History and World Communism. Vol. 114. New York: Praeger. pp. 245–302. LCCN 62-17560. OCLC 254495418.

- Magocsi, Paul R. (1996). A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-0830-5. OCLC 757049758.

- Makhno, Nestor (2009). Skirda, Alexandre (ed.). Mémoires et écrits: 1917–1932 (in French). Paris: Ivrea. ISBN 978-2851842862. OCLC 690866794.

- Makhno, Nestor (2007) [1928]. The Russian Revolution in Ukraine (March 1917 – April 1918). Translated by Archibald, Malcolm. Edmonton: Black Cat Press. ISBN 978-0973782714. OCLC 187835001.

- Makhno, Nestor (1996). Skirda, Alexandre (ed.). The Struggle Against the State and Other Essays. Translated by Sharkey, Paul. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 1873176783. OCLC 924883878.

- Marshall, Peter H. (1993). "Russia and the Ukraine". Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: Fontana Press. pp. 469–478. ISBN 978-0-00-686245-1. OCLC 1042028128.

- Malet, Michael (1982). Nestor Makhno in the Russian Civil War. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-25969-6. OCLC 1194667963.

- Palij, Michael (1976). The Anarchism of Nestor Makhno, 1918–1921. Publications on Russia and Eastern Europe of the Institute for Comparative and Foreign Area Studies. Vol. 7. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295955112. OCLC 2372742.

- Patterson, Sean (2020). Makhno and Memory: Anarchist and Mennonite Narratives of Ukraine's Civil War, 1917–1921. Manitoba: University of Manitoba Press. ISBN 978-0-88755-578-7. OCLC 1134608930.

- Peters, Victor (1970). Nestor Makhno: The Life of an Anarchist. Winnipeg: Echo Books. OCLC 7925080.

- Shubin, Aleksandr (2010). "The Makhnovist Movement and the National Question in the Ukraine, 1917–1921". In Hirsch, Steven J.; van der Walt, Lucien (eds.). Anarchism and Syndicalism in the Colonial and Postcolonial World, 1870–1940. Studies in Global Social History. Vol. 6. Leiden: Brill. pp. 147–191. ISBN 978-9004188495. OCLC 868808983.

- Skirda, Alexandre (2004) [1982]. Nestor Makhno: Anarchy's Cossack. Translated by Sharkey, Paul. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 1-902593-68-5. OCLC 58872511.

- Subtelny, Orest (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-5808-9. OCLC 20722741.

- Sysyn, Frank (1977). "Nestor Makhno and the Ukrainian Revolution". In Hunczak, Taras (ed.). The Ukraine, 1917–1921: A Study in Revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 271–304. ISBN 978-0674920095. OCLC 942852423. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- Volin (1947). The Unknown Revolution: 1917–1921, Book III, the struggle for real social revolution, Part II: Ukraine (1918–1921).