Management of prostate cancer

Treatment for prostate cancer may involve active surveillance, surgery, radiation therapy – including brachytherapy (prostate brachytherapy) and external-beam radiation therapy, proton therapy, high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), cryosurgery, hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, or some combination. Treatments also extend to survivorship based interventions. These interventions are focused on five domains including: physical symptoms, psychological symptoms, surveillance, health promotion and care coordination.[1] However, a published review has found only high levels of evidence for interventions that target physical and psychological symptom management and health promotion, with no reviews of interventions for either care coordination or surveillance.[2] The favored treatment option depends on the stage of the disease, the Gleason score, and the PSA level. Other important factors include the man's age, his general health, and his feelings about potential treatments and their possible side-effects. Because all treatments can have significant side-effects, such as erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence, treatment discussions often focus on balancing the goals of therapy with the risks of lifestyle alterations.

| Management of prostate cancer | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | oncology |

If the cancer has spread beyond the prostate, treatment options change significantly, so most doctors who treat prostate cancer use a variety of nomograms to predict the probability of spread. Treatment by watchful waiting/active surveillance, HIFU, external-beam radiation therapy, brachytherapy, cryosurgery, and surgery are, in general, offered to men whose cancer remains within the prostate. Clinicians may reserve hormonal therapy and chemotherapy for disease that has spread beyond the prostate. However, there are exceptions: radiation therapy can treat some advanced tumors, and hormonal therapy some early-stage tumors. Doctors may also propose cryotherapy (the process of freezing the tumor), hormonal therapy, or chemotherapy if initial treatment fails and the cancer progresses.[3]

Active surveillance

Active surveillance is observation and regular monitoring without invasive treatment. In the context of prostate disease this usually comprises regular PSA blood tests and prostate biopsies. Active surveillance is often used when an early stage, slow-growing prostate cancer is suspected. However, watchful waiting may also be suggested when the risks of surgery, radiation therapy, or hormonal therapy outweigh the possible benefits. Other treatments can be started if symptoms develop, or if there are signs that the cancer growth is accelerating .

Approximately one-third of men who choose active surveillance for early-stage tumors eventually have signs of tumor progression, and they may need to begin treatment within three years.[4] Men that choose active surveillance avoid the risks of surgery, radiation, and other treatments. The risk of disease progression and metastasis (spread of the cancer) may be increased, but this increase risk appears to be small if the program of surveillance is followed closely, generally including serial PSA assessments and repeat prostate biopsies every 1–2 years depending on the PSA trends.

Study results in 2011 suggest active surveillance is the best choice for older 'low-risk' patients.[5]

Surgery

Surgical removal of the prostate, or prostatectomy, is a common treatment either for early-stage prostate cancer or for cancer that has failed to respond to radiation therapy. The most common type is radical retropubic prostatectomy, when the surgeon removes the prostate through an abdominal incision. Another type is radical perineal prostatectomy, when the surgeon removes the prostate through an incision in the perineum, the skin between the scrotum and anus. Radical prostatectomy can also be performed laparoscopically, through a series of small (1 cm) incisions in the abdomen, with or without the assistance of a surgical robot.

Radical prostatectomy

Radical prostatectomy is effective for tumors that have not spread beyond the prostate;[6] cure rates depend on risk factors such as PSA level and Gleason grade. However, it may cause nerve damage that may significantly alter the quality of life of the prostate cancer survivor. Radical prostatectomy has been associated with a greater decrease in sexual function and increased urinary incontinence (mainly stress incontinence) than external beam radiotherapy, an alternative treatment.[7]

Radical prostatectomy has traditionally been used alone when the cancer is localized to the prostate. In the event of positive margins or locally advanced disease found on pathology, adjuvant radiation therapy may offer improved survival. Surgery may also be offered when a cancer is not responding to radiation therapy. However, because radiation therapy causes tissue changes, prostatectomy after radiation has higher risks of complications.

To avoid the adverse side effects of a radical prostatectomy, doctors may recommend deferred treatment which can involve observation and palliative treatment or active monitoring with some local treatments as needed. When compared with observation and palliative treatment, radical prostatectomy probably reduces the risk of dying for any reason, including dying from prostate cancer.[8] Between radical prostatectomy and active monitoring, the risk of dying for any reason, including from prostate cancer, is likely the same.[8] The surgery also probably reduces the risk of the cancer spreading or becoming more aggressive.[8] Erection problems and urine leakage are probably more likely for patients who receive surgery than those who receive active monitoring or observation.[8]

Laparoscopic approach

Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (LRP) is a new way to approach the prostate surgically with intent to cure. Contrasted with the open surgical form of prostate cancer surgery, laparoscopic radical prostatectomy requires a smaller incision. Relying on modern technology, such as miniaturization, fiber optics, laparoscopic radical prostatectomy is a minimally invasive prostate cancer treatment but is technically demanding and seldom performed in the United States.

Robotic assistance

Some believe that in the hands of an experienced surgeon, robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALP) may reduce positive surgical margins when compared to radical retropubic prostatectomy (RRP) among patients with prostate cancer according to a retrospective study.[9] The relative risk reduction was 57.7%. For patients at similar risk to those in this study (35.5% of patients had positive surgical margins following RRP), this leads to an absolute risk reduction of 20.5%. 4.9 patients must be treated for one to benefit (number needed to treat = 4.9). Other recent studies have shown RALP to result in a significantly higher rate of positive margins.[10] Other studies showed no difference of robotic to open surgery.[11] A review comprehensively analyzed the evidence from studies in men with prostate cancer that compared RALP with open radical prostatectomy and found no difference in the reduction of mortality from this cancer, the recurrence or all-cause mortality.[12] The quality of life with both procedures would be similar in relation to urinary and sexual function, and there appear to be no differences in postoperative surgical complications.[12] Robotic surgery can have a small effect on postoperative pain between right after surgery, a shorter hospital stay and a lower requirement for blood transfusions.[12]

One common problem associated with this surgery is incontinence, or urinary leakage, which occurs for 6–12 months after the removal of the catheter placed during surgery. When using RALP, surgeons can either proceed with a standard approach or use an approach that doesn't cut the tissue connections between the front of the bladder and the back of the abdominal wall, Retzius-sparing RALP.[13] Retzius-sparing RALP probably improves continence within one week after catheter removal but may be more likely to leave positive surgical margins that could allow the cancer to come back.[13] Retzius-sparing RALP may also reduce urinary leakage between 3–6 months after surgery, but by 12 months continence is likely similar.[13]

Transurethral resection

Transurethral resection of the prostate, commonly called a "TURP," is a surgical procedure performed when the tube from the bladder to the penis (urethra) is blocked by prostate enlargement. In general, TURP is done for benign prostatic hyperplasia and is not meant as definitive treatment for prostate cancer. During a TURP, a small instrument (cystoscope) is placed into the penis and the blocking prostate is cut away by cautery.

Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery is a minimally invasive method of treating prostate cancer in which the prostate gland is exposed to freezing temperatures.[14] Under ultrasound guidance metal rods are inserted through the skin of the perineum into the prostate. Highly purified argon gas is used to cool the rods, freezing the surrounding tissue at −186 °C (−302 °F). As the water within the prostate cells freezes, the cells die. The urethra is protected from freezing by a catheter filled with warm liquid. General anesthesia is less commonly used for cryosurgery meaning it can often be performed in an outpatient clinic setting.[15]

It is not clear if cryosurgery improves the quality of life and mortality from prostate cancer compared to radiation therapy.[15] Potential adverse effects associated with cryosurgery include urinary retention, incontinence, and pain in the perineal region, penis, or scrotum.[15] Impotence occurs up to ninety percent of the time. The potential for severe adverse effects compared to radiation treatment is not clear.[15] Cryosurgery is less invasive than radical prostatectomy.

Surgical removal of the testicles

In metastatic disease, where cancer has spread beyond the prostate, removal of the testicles (called orchiectomy) may be done to decrease testosterone levels and control cancer growth. (See hormonal therapy, below).

Complications of surgery

The most common serious complications of surgery are loss of urinary control and impotence. Reported rates of both complications vary widely depending on how they are assessed, by whom, and how long after surgery, as well as the setting (e.g., academic series vs. community-based or population-based data).

Erectile dysfunction

Although penile sensation and the ability to achieve orgasm usually remain intact, erection and ejaculation are often impaired. Medications such as sildenafil (Viagra), tadalafil (Cialis), or vardenafil (Levitra) may restore some degree of potency. For men struggling with erections after a prostatectomy, taking medication on a scheduled basis may result in a similar self-reported rate and quality of erections as taking medication as needed.[16] There may also be similar rates of serious unwanted side effects for both types of medication usage.[16] For most men with organ-confined disease, a more limited "nerve-sparing" technique may help reduce urinary incontinence and impotence.[17][18]

Urinary incontinence

Radical prostatectomy, transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), and radiation therapy are the main causes of stress incontinence in men, with radical prostatectomy being the top cause.[19] In most cases, the incontinence resolves within 12 months with conservative treatment. Multiple factors, such as injury of the urethral sphincter or nervous bundles can play a role, causing mostly stress incontinence.[20] Stress urinary incontinence happens when the urethral sphincter (the muscular sphincter that closes the bladder) fails to properly close, leading to leakage of urine in situations where the abdominal pressure is higher than usual, such as when laughing, sneezing, or coughing.

Conservative treatment, such as pelvic floor muscle training (Kegel exercise) has been prescribed to improve urinary continence, the evidence for efficacy in men after radical prostatectomy has come into question. According to information from the Men After Prostate Surgery (MAPS) randomized control trial, pelvic floor muscle training was not shown to be therapeutic or cost effective in improving urinary continence.[21]

Other therapies include the use of penile clamps, transurethral bulking agents, and catheters, however, the most commonly used surgical therapies performed are the placement of a urethral sling or artificial urinary sphincter.[19] For people with moderate to severe stress urinary incontinence after prostate surgery, artificial urinary sphincter is the treatment of choice, after all the other conservative measures fail.[22]

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy, also known as radiotherapy, is often used to treat all stages of prostate cancer. It is also often used after surgery if the surgery was not successful at curing the cancer. Radiotherapy uses ionizing radiation to kill prostate cancer cells. When absorbed in tissue, ionizing radiation such as gamma and x-rays damage the DNA in cancer cells, which increases the probability of apoptosis (cell death). Normal cells are able to repair radiation damage, while cancer cells are not. Radiation therapy exploits this fact to treat cancer. Radiation therapy used in prostate cancer treatment include external beam radiation therapy and brachytherapy (specifically prostate brachytherapy).

External beam radiation therapy

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) uses a linear accelerator to produce high-energy x-rays that are directed in a beam towards the prostate. A technique called Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy (IMRT) may be used to adjust the radiation beam to conform with the shape of the tumor, allowing higher doses to be given to the prostate and seminal vesicles with less damage to the bladder and rectum. External beam radiation therapy is generally given over several weeks, with daily visits to a radiation therapy center. New types of radiation therapy such as IMRT have fewer side effects than traditional treatment. However, in the short term, EBRT has been associated with acute worsening of urinary obstructive and bowel symptoms. These symptoms have been shown to decline over time.[7] Thirty-Six centers in the United States are now using proton therapy for prostate cancer, which uses protons rather than X-rays to kill the cancer cells.[23] Researchers are also studying types of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) to treat prostate cancer

Brachytherapy

Permanent implant brachytherapy is a popular treatment choice for patients with low to intermediate risk features, can be performed on an outpatient basis, and is associated with good 10-year outcomes with relatively low morbidity.[24] It involves the placement of about 100 small "seeds" containing radioactive material (such as iodine-125 or palladium-103) with a needle through the skin of the perineum directly into the tumor while under spinal or general anesthetic. These seeds emit lower-energy X-rays which are only able to travel a short distance. Although the seeds eventually become inert, they remain in the prostate permanently. The risk of exposure to others from men with implanted seeds is generally accepted to be insignificant.[25] However, men are encouraged to talk to their doctors about any special temporary precautions around small children and pregnant women.[26]

Uses

Radiation therapy is commonly used in prostate cancer treatment. It may be used instead of surgery or after surgery in early-stage prostate cancer (adjuvant radiotherapy). Radiation treatments also can be combined with hormonal therapy for intermediate risk disease, when surgery or radiation therapy alone is less likely to cure the cancer. Some radiation oncologists combine external beam radiation and brachytherapy for intermediate to high-risk situations. Radiation therapy is often used in conjunction with hormone therapy for high-risk patients.[27]

For men over 64 with prostate cancer limited to the pelvis, using fewer, larger doses of radiation (hypofractionation) results in similar overall survival rates.[28] The risk of dying from prostate cancer or having acute bladder side effects may be similar to that of longer radiation treatment.[28] Others use a "triple modality" combination of external beam radiation therapy, brachytherapy, and hormonal therapy. In advanced stages of prostate cancer, radiation is used to treat painful bone metastases or reduce spinal cord compression.

Radiation therapy is also used after radical prostatectomy either for cancer recurrence or if multiple risk factors are found during surgery. Radiation therapy delivered immediately after surgery when risk factors are present (positive surgical margin, extracapsular extension, seminal vessicle involvement) has been demonstrated to reduce cancer recurrence, decrease distant metastasis, and increase overall survival in two separate randomized trials.[29]

Side effects

Side effects of radiation therapy might occur after a few weeks into treatment. Both types of radiation therapy may cause diarrhea and mild rectal bleeding due to radiation proctitis, as well as potential urinary incontinence and impotence. Symptoms tend to improve over time except for erections which typically worsen as time progresses.

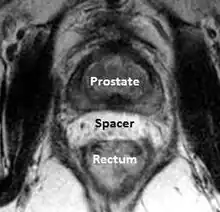

A new method to reduce rectal radiation injury in prostate cancer patients involves the use of an absorbable spacer placed between the prostate and rectum.

Such spacers are commercially available in some regions and are undergoing clinical trials in others.[30] By temporarily altering the anatomy these products have the potential to allow for improved cancer targeting while minimizing risk to neighboring healthy tissues. Prostate rectum spacers should be compatible with all prostate cancer radiotherapy treatments including 3D conformal, IMRT and stereotactic radiation and brachytherapy.

Comparison to surgery

Multiple retrospective analyses have demonstrated that overall survival and disease-free survival outcomes are similar between radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, and brachytherapy.[31] However, a recent retrospective study suggests that men under 60 with high grade prostate cancer have higher survival rates with surgery than with beam radiation.[32] Rates for impotence when comparing radiation to nerve-sparing surgery are similar. Radiation has lower rates of incontinence compared with surgery, but has higher rates of occasional mild rectal bleeding.[33] Men who have undergone external beam radiation therapy may have a slightly higher risk of later developing colon cancer and bladder cancer.[34]

Since prostate cancer is generally a multifocal disease, the traditional prostatectomy eliminates all local lesions by removing the entire prostate. However, it has been hypothesized that an "index lesion" might be responsible for disease progression. Therefore, focal therapy targeted towards the index lesion might effectively treat prostate cancer while preserving the remainder of the gland. Interventional radiologists have started to treat prostate cancer with minimally invasive therapies such as cryoablation, HIFU, radiofrequency ablation, and photodynamic therapy that permit focal therapy by utilizing image guidance. These therapies are still in beginning or experimental stages; however, because they preserve tissue, they can potentially reduce adverse treatment outcomes such as impotence and incontinence. A small prospective study published in European Urology in February 2015 assessed the focal treatment of index lesions with HIFU in patients with multifocal prostate cancer and found that the majority of men returned to baseline genitourinary function and 86% of men were free of clinically significant prostate cancer at one year.[35] Small, nonrandomized cohort studies with a median range follow-up 17–47 months have shown that cryoablation, HIFU, and phototherapy are associated with low rates of adverse effects and early disease control rates of 83–100% based on negative biopsies.[36]

People with prostate cancer who might particularly benefit from focal therapy with HIFU are men with recurrent cancer after the gland has been removed. Cancer recurrence rates after surgical resection can be as high as 15–20%. MR imaging improves early detection of cancer, so MR-guided therapies can be applied to treat recurrent disease. Additionally, for men who have already failed salvage radiation treatment and have limited therapeutic options remaining, interventional therapies might offer more chances to potentially cure their disease. While recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of these treatments, additional work is needed to further evaluate which patients are best suited for these procedures and determine long-term efficacy.[37]

High intensity focused ultrasound

High intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) was first used in the 1940s and 1950s in efforts to destroy tumors in the central nervous system. Since then, HIFU has been shown to be effective at destroying malignant tissue in the brain, prostate, spleen, liver, kidney, breast, and bone.[38]

HIFU for prostate cancer utilizes ultrasound to ablate/destroy the tissue of the prostate. During the HIFU procedure, sound waves are used to heat the prostate tissue, thus destroying the cancerous cells. In essence, ultrasonic waves are focused on specific areas of the prostate to eliminate the prostate cancer, with minimal risks of affecting other tissue or organs. Temperatures at the focal point of the sound waves can exceed 100 °C (212 °F).[38] However, many studies of HIFU were performed by manufacturers of HIFU devices, or members of manufacturers' advisory panels.[39]

Contraindications to HIFU for prostate cancer include a prostate volume larger than 40 grams, which can prevent targeted HIFU waves from reaching the anterior and anterobasal regions of the prostate, anatomic or pathologic conditions that may interfere with the introduction or displacement of the HIFU probe into the rectum, and high-volume calcification within the prostate, which can lead to HIFU scattering and transmission impairment.[40]

A 2012 UK trial of focal HIFU on 41 patients reported no histological evidence of cancer in 77% of men treated (95% confidence interval: 61–89%) at 12 month targeted biopsy, and a low rate of genitourinary side effects.[41] However, this does not necessarily mean that 77% of men were definitively cured of prostate cancer, since systematic and random sampling errors are present in the biopsy process, and therefore recurrent or previously undetected cancer can be missed.[42]

Life-style changes

Prostate enlargement can cause difficulties emptying the bladder completely. This situation, in which there is residual volume in the bladder is prone to complications such as cystitis and bladder stones, also commonly found in patients with benign prostate hyperplasia. It was often suggested to change the voiding position of symptomatic males, however study results showed heterogeneity. A meta-analysis of people with prostate enlargement and healthy males showed a significant reduction of residual volume, while a trend towards an improved urinary flow rate and decreased voiding time was found.[43] The effect of changing ones position is thought to arise from relaxation of the pelvic musculature, which are contracted in the standing position thereby influencing urodynamics.

There is some evidence that exercise may be beneficial for people with prostate cancer, however the effects are not clear.[44]

Hormonal therapy

Androgen deprivation therapy

Hormonal therapy uses medications or surgery to block prostate cancer cells from getting dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a hormone produced in the prostate and required for the growth and spread of most prostate cancer cells. Blocking DHT often causes prostate cancer to stop growing and even shrink. However, hormonal therapy rarely cures prostate cancer because cancers that initially respond to hormonal therapy typically become resistant after one to two years. Hormonal therapy is, therefore, usually used when cancer has spread from the prostate. It may also be given to certain men undergoing radiation therapy or surgery to help prevent return of their cancer.[45]

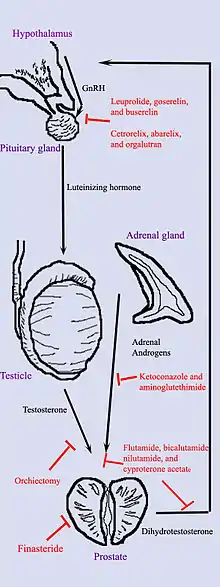

Hormonal therapy for prostate cancer targets the pathways the body uses to produce DHT. A feedback loop involving the testicles, the hypothalamus, and the pituitary, adrenal, and prostate glands controls the blood levels of DHT. First, low blood levels of DHT stimulate the hypothalamus to produce gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). GnRH then stimulates the pituitary gland to produce luteinizing hormone (LH), and LH stimulates the testicles to produce testosterone. Finally, testosterone from the testicles and dehydroepiandrosterone from the adrenal glands stimulate the prostate to produce more DHT. Hormonal therapy can decrease levels of DHT by interrupting this pathway at any point. There are several forms of hormonal therapy:

- Orchiectomy, also called "castration," is surgery to remove the testicles. Because the testicles make most of the body's testosterone, after orchiectomy testosterone levels drop. Now the prostate not only lacks the testosterone stimulus to produce DHT but also does not have enough testosterone to transform into DHT. Orchiectomy is considered the gold standard of treatment.[46]

- Antiandrogens are medications such as flutamide, nilutamide, bicalutamide, enzalutamide, apalutamide, and cyproterone acetate that directly block the actions of testosterone and DHT within prostate cancer cells.

- In men with metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer, doctors may recommend adding taxane-based chemotherapy (docetaxel) to hormone therapy.[47] This combination likely improves overall and cancer-specific survival by slowing the spread of the cancer. However, taxane-based chemotherapy may cause an increase in side effects.[47]

- Medications that block the production of adrenal androgens such as DHEA include ketoconazole and aminoglutethimide. Because the adrenal glands make only about 5% of the body's androgens, these medications are, in general, used only in combination with other methods that can block the 95% of androgens made by the testicles. These combined methods are called total androgen blockade (TAB). TAB can also be achieved using antiandrogens.

- GnRH action can be interrupted in one of two ways. GnRH antagonists such as abarelix and degarelix suppress the production of LH directly by acting on the anterior pituitary. GnRH agonists such as leuprorelin and goserelin suppress LH through the process of downregulation after an initial stimulation effect which can cause initial tumor flare. In order to prevent stimulation of tumor growth during the initial LH surge, an antiandrogen such as cyproterone acetate is prescribed a week before and three weeks after GnRH agonists are given. Abarelix and degarelix are examples of GnRH antagonists, whereas the GnRH agonists include leuprolide, goserelin, triptorelin, and buserelin. Initially, GnRH agonists increase the production of LH. However, because the constant supply of the medication does not match the body's natural production rhythm, production of both LH and GnRH decreases after a few weeks.[48]

- Abiraterone acetate was FDA approved in April 2011 for treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer for patients who have failed docetaxel therapy. Abiraterone acetate inhibits an enzyme known as CYP17, which is used in the body to produce testosterone.[49][50] A review from 2020 showed that when abiraterone acetate is used in combination with hormone therapy improves overall survival for men with prostate cancer and also increases the risk of severe and life-threatening side effects that leads to discontinuation of treatment with these drugs.[51]

The most successful hormonal treatments are orchiectomy and GnRH agonists. Despite their higher cost, GnRH agonists are often chosen over orchiectomy for cosmetic and emotional reasons. Eventually, total androgen blockade may prove to be better than orchiectomy or GnRH agonists used alone.

Each treatment has disadvantages that limit its use in certain circumstances. Although orchiectomy is a low-risk surgery, the psychological impact of removing the testicles can be significant, and sterility is certain. The loss of testosterone can cause hot flashes, weight gain, loss of libido, enlargement of the breasts (gynecomastia), impotence, penile atrophy, and osteoporosis. GnRH agonists eventually cause the same side effects as orchiectomy but may cause worse symptoms at the beginning of treatment. When GnRH agonists are first used, testosterone surges can lead to increased bone pain from metastatic cancer, so antiandrogens or abarelix is often added to blunt these side effects. Estrogens are not commonly used because they increase the risk for cardiovascular disease and blood clots. In general, the antiandrogens do not cause impotence, and usually cause less loss of bone and muscle mass. Ketoconazole can cause liver damage with prolonged use, and aminoglutethimide can cause skin rashes.

When hormonal treatment is appropriate, doctors may choose to start treatment early, right after the diagnosis is made, or wait until the cancer has begun to grow. For men with advanced prostate cancer early hormonal treatment probably lowers the risk of dying from any cause, including dying from prostate cancer without severely affecting quality of life.[52] However, early treatment may lead to more tiredness and heart weakness.[52]

One 2021 study from JAMA Oncology aimed to compare the effectiveness and safety determined in randomized clinical trials of systemic treatments for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC). The study found that "as add-on treatments to ADT, abiraterone acetate and apalutamide may provide the largest overall survival benefits with relatively low SAE risks. Although enzalutamide may improve radiographic progression-free survival to the greatest extent, longer follow-up is needed to examine the overall survival benefits associated with enzalutamide."[53]

Estrogen therapy

High-dose estrogen therapy is used in the treatment of prostate cancer.[54] Estrogens that have been used include diethylstilbestrol, fosfestrol, ethinylestradiol, ethinylestradiol sulfonate, polyestradiol phosphate, and estradiol undecylate, as well as the dual estrogenic and cytostatic agent estramustine phosphate.[54][55] Newer estrogens with improved tolerability and safety like GTx-758 have also been studied.[56][57] Estrogens are effective in prostate cancer because they are functional antiandrogens.[55][58] They both suppress testosterone levels into the castrate range via their antigonadotropic effects[55][58] and they reduce the fraction of free and bioavailable testosterone by increasing sex hormone-binding globulin levels.[56][58] Estrogens may also have direct cytotoxic effects in the prostate gland.[55]

Estrogens have been found to be equivalent in effectiveness to androgen deprivation therapy via surgical or medical castration and nonsteroidal antiandrogens.[58] In addition, they prevent hot flashes, preserve bone density, preserve some sexual interest, have quality-of-life advantages, and are far less costly than conventional androgen deprivation therapy.[59][60][61][62][63][64][65] However, estrogens cause feminization and gynecomastia as side effects.[60][61][62][64][65] Moreover, at a dosage of 3 to 5 mg/day, diethylstilbestrol can increase cardiovascular mortality – particularly in those patients who already have a compromised cardiovascular system. Diethylstilbestrol at 1 to 2 mg/day appears to be safe and effective for CRPC patients who have healthy cardiovascular systems and who concurrently take low-dose aspirin.[58] Although the most commonly employed estrogens, oral and synthetic estrogens such as diethylstilbestrol and ethinylestradiol, increase cardiovascular mortality, certain estrogens, namely bioidentical parenteral estrogens such as polyestradiol phosphate and high-dose transdermal estradiol, do so limitedly or not at all; this is attributed to different degrees of effect of the estrogen classes on liver protein synthesis and by extension coagulation factors.[58]

| Route/form | Estrogen | Dosage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Estradiol | 1–2 mg 3x/day | |

| Conjugated estrogens | 1.25–2.5 mg 3x/day | ||

| Ethinylestradiol | 0.15–3 mg/day | ||

| Ethinylestradiol sulfonate | 1–2 mg 1x/week | ||

| Diethylstilbestrol | 1–3 mg/day | ||

| Dienestrol | 5 mg/day | ||

| Hexestrol | 5 mg/day | ||

| Fosfestrol | 100–480 mg 1–3x/day | ||

| Chlorotrianisene | 12–48 mg/day | ||

| Quadrosilan | 900 mg/day | ||

| Estramustine phosphate | 140–1400 mg/day | ||

| Transdermal patch | Estradiol | 2–6x 100 μg/day Scrotal: 1x 100 μg/day | |

| IMTooltip Intramuscular or SC injection | Estradiol benzoate | 1.66 mg 3x/week | |

| Estradiol dipropionate | 5 mg 1x/week | ||

| Estradiol valerate | 10–40 mg 1x/1–2 weeks | ||

| Estradiol undecylate | 100 mg 1x/4 weeks | ||

| Polyestradiol phosphate | Alone: 160–320 mg 1x/4 weeks With oral EE: 40–80 mg 1x/4 weeks | ||

| Estrone | 2–4 mg 2–3x/week | ||

| IV injection | Fosfestrol | 300–1200 mg 1–7x/week | |

| Estramustine phosphate | 240–450 mg/day | ||

| Note: Dosages are not necessarily equivalent. Sources: See template. | |||

Recurrent disease

After surgery or radiation therapy, PSA may start to rise again, which is called biochemical recurrence if a certain threshold is met in PSA levels (typically 0.1 or 0.2 ng/ml for surgery). At 10 years of follow-up after surgery, there is an overall risk of biochemical recurrence of 30–50%, depending on the initial risk state, and salvage radiation therapy (SRT) is the only curative treatment.[66] SRT is often administered in combination with androgen deprivation therapy for up to two years. A retrospective study of patients treated with SRT between 1987 and 2013 found that 56% of 2460 patients were free from biochemical failure after 5 years follow-up.[67] Among those with a PSA less than 0.2 before SRT, this was 71%.

Extensive disease

Palliative care for advanced-stage prostate cancer focuses on extending life and relieving the symptoms of metastatic disease. As noted above, abiraterone is showing some promise in treating advanced-stage prostate cancer. It causes a dramatic reduction in PSA levels and tumor sizes in aggressive advanced-stage prostate cancer for 70% of patients.[49][50] Chemotherapy may be offered to slow disease progression and postpone symptoms. The most commonly used regimen combines the chemotherapeutic drug docetaxel with a corticosteroid such as prednisone. One study showed that treatment with docetaxel with prednisone prolonged life from 16.5 months for those taking mitoxantrone and prednisone to 18.9 months for those taking docetaxel + prednisone.[68] Bisphosphonates such as zoledronic acid have been shown to delay skeletal complications such as fractures or the need for radiation therapy in patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer.[69] Xofigo is a new alpha-emitting pharmaceutical targeting bone metastasis. Phase II testing shows prolonged patient survival times, reduced pain, and improved quality of life.

Bone pain due to metastatic disease is treated with opioid pain relievers such as morphine and oxycodone. External beam radiation therapy directed at bone metastases may provide pain relief. Injections of certain radioisotopes, such as strontium-89, phosphorus-32, or samarium-153, also target bone metastases and may help relieve pain.

For men with prostate cancer and bone metastases zoledronic acid (a bisphosphonate) and denosumab (a RANK-ligand-inhibitor) appear to be the most effective in preventing skeletal complications.[70] However these agents also seem to cause more frequent and severe adverse events, including kidney failure for treatment with zoledronic acid and osteonecrosis of the jaw for denosumab.[70]

Alternative therapies

As an alternative to active surveillance or definitive treatments, other therapies are also under investigation for the management of prostate cancer. PSA has been shown to be lowered in men with apparent localized prostate cancer using a vegan diet (fish allowed), regular exercise, and stress reduction.[71] These results have so far proven durable after two-years' treatment. However, this study did not compare the vegan diet to either active surveillance or definitive treatment, and thus cannot comment on the comparative efficacy of the vegan diet in treating prostate cancer.[72]

Many other single agents have been shown to reduce PSA, slow PSA doubling times, or have similar effects on secondary markers in men with localized cancer in short term trials, such as pomegranate juice or genistein, an isoflavone found in various legumes.[73][74]

The potential of using multiple such agents in concert, let alone combining them with lifestyle changes, has not yet been studied. A more thorough review of natural approaches to prostate cancer has been published.[75]

Neutrons have been shown to be superior to X-rays in the treatment of prostatic cancer. The rationale is that tumours containing hypoxic cells (cells with enough oxygen concentration to be viable, yet not enough to be X-ray-radiosensitive) and cells deficient in oxygen are resistant to killing by X-rays. Thus, the lower Oxygen Enhancement Ratio (OER) of neutrons confers an advantage. Also, neutrons have a higher relative biological effectiveness (RBE) for slow-growing tumours than X-rays, allowing for an advantage in tumour cell killing.[76]

Prevention

Neither selenium nor vitamin E have been found to be effective in preventing prostate cancer.[77]

Trade-offs

The trade-off dilemma refers to the choice between the expected beneficial and harmful effects in terms of survival and quality of life for a particular treatment. An example of such trade-off in prostate cancer treatment includes urinary and bowel symptoms and waning sexual function.[78] How common these symptoms are and the distress they cause varies between types of treatment and individuals.[79]

One option is to trade off an intact sexual function for the possibility of a prolonged life expectancy by not having curative treatment. The choice involves a trade-off so it is of central importance for the person and the physician to have access to information on established treatment benefits and side effects. A Swedish study found that the willingness to do this kind of trade-off varied considerably among men.[78] While six out of ten were willing to consider a trade-off between life expectancy and intact sexual function, given the present knowledge of treatment benefits for clinically localized prostate cancer, four out of ten stated that they would under all circumstances choose treatment irrespective of the risk for waning sexual function. Access to valid empirical information is crucial for such decision making. Key factors here are an individual's feeling towards the illness, their emotional values and religious beliefs. A substantial proportion of people and physicians, experience stress in judging the trade-off between different treatment options and treatment side-effects which adds to the stress of cancer diagnosed, a situation made worse in that eight out of ten people with prostate cancer have no one to confide in except their spouse and one out of five live in total emotional isolation.[80] The American Urological Association (AUA), American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO), and the Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) have issued joint guidelines on shared decision making with patients who have localized prostate cancer to help patients navigate these decisions.[81]

See also

References

- Resnick MJ, Lacchetti C, Bergman J, Hauke RJ, Hoffman KE, Kungel TM, et al. (March 2015). "Prostate cancer survivorship care guideline: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline endorsement". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 33 (9): 1078–85. doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2557. PMID 25667275. S2CID 24355867.

- Crawford-Williams F, March S, Goodwin BC, Ralph N, Galvão DA, Newton RU, et al. (October 2018). "Interventions for prostate cancer survivorship: A systematic review of reviews" (PDF). Psycho-Oncology. 27 (10): 2339–2348. doi:10.1002/pon.4888. PMID 30255558. S2CID 52823451.

- "Prostate Cancer At A Glance". shavemagazine.com. Archived from the original on 2018-07-14. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- Wu H, Sun L, Moul JW, Wu HY, McLeod DG, Amling C, et al. (March 2004). "Watchful waiting and factors predictive of secondary treatment of localized prostate cancer". The Journal of Urology. 171 (3): 1111–6. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000113300.74132.8b. PMID 14767282.

- "Active Surveillance May Be Preferred Option in Some Men with Prostate Cancer". Archived from the original on 3 May 2011.

- Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Ruutu M, Häggman M, Andersson SO, Bratell S, Spångberg A, Busch C, Nordling S, Garmo H, Palmgren J, Adami HO, Norlén BJ, Johansson JE (May 2005). "Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer". New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (19): 1977–84. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043739. PMID 15888698. S2CID 44790644.

- Chen C, Chen Z, Wang K, Hu L, Xu R, He X (November 2017). "Comparisons of health-related quality of life among surgery and radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Oncotarget. 8 (58): 99057–65. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.21519. PMC 5716791. PMID 29228751.

- Vernooij RW, Lancee M, Cleves A, Dahm P, Bangma CH, Aben KK (June 2020). "Radical prostatectomy versus deferred treatment for localised prostate cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (6): CD006590. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006590.pub3. PMC 7270852. PMID 32495338.

- Smith JA, Chan RC, Chang SS, Herrell SD, Clark PE, Baumgartner R, Cookson MS (December 2007). "A comparison of the incidence and location of positive surgical margins in robotic assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy and open retropubic radical prostatectomy". The Journal of Urology. 178 (6): 2385–9, discussion 2389–90. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.008. PMID 17936849.

- Ou YC, Yang CR, Wang J, Cheng CL, Patel VR (May 2009). "Comparison of robotic-assisted versus retropubic radical prostatectomy performed by a single surgeon". Anticancer Research. 29 (5): 1637–42. PMID 19443379.

- Ham WS, Park SY, Rha KH, Kim WT, Choi YD (June 2009). "Robotic radical prostatectomy for patients with locally advanced prostate cancer is feasible: results of a single-institution study". Journal of Laparoendoscopic & Advanced Surgical Techniques. Part A. 19 (3): 329–32. doi:10.1089/lap.2008.0344. PMID 19397390.

- Ilic D, Evans SM, Allan CA, Jung JH, Murphy D, Frydenberg M, et al. (Cochrane Urology Group) (September 2017). "Laparoscopic and robotic-assisted versus open radical prostatectomy for the treatment of localised prostate cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (9): CD009625. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009625.pub2. PMC 6486168. PMID 28895658.

- Rosenberg JE, Jung JH, Edgerton Z, Lee H, Lee S, Bakker CJ, Dahm P, et al. (Cochrane Urology Group) (August 2020). "Retzius-sparing versus standard robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy for the treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (8): CD013641. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013641.pub2. PMC 7437391. PMID 32813279.

- PreventProstateCancer.info: A Brief Overview of Prostate Cancer Archived 2008-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Jung JH, Risk MC, Goldfarb R, Reddy B, Coles B, Dahm P, et al. (Cochrane Urology Group) (May 2018). "Primary cryotherapy for localised or locally advanced prostate cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (5): CD005010. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005010.pub3. PMC 6494517. PMID 29845595.

- Philippou YA, Jung JH, Steggall MJ, O'Driscoll ST, Bakker CJ, Bodie JA, Dahm P, et al. (Cochrane Urology Group) (October 2018). "Penile rehabilitation for postprostatectomy erectile dysfunction". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (10): CD012414. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012414.pub2. PMC 6517112. PMID 30352488.

- Gerber GS, Thisted RA, Scardino PT, Frohmuller HG, Schroeder FH, Paulson DF, et al. (August 1996). "Results of radical prostatectomy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer". JAMA. 276 (8): 615–9. doi:10.1001/jama.276.8.615. PMID 8773633.

- "Erectile Dysfunction". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- Trost L, Elliott DS (2012). "Male stress urinary incontinence: a review of surgical treatment options and outcomes". Advances in Urology. 2012: 287489. doi:10.1155/2012/287489. PMC 3356867. PMID 22649446.

- Hoyland K, Vasdev N, Abrof A, Boustead G (2014). "Post-radical prostatectomy incontinence: etiology and prevention". Reviews in Urology. 16 (4): 181–8. PMC 4274175. PMID 25548545.

- Glazener C, Boachie C, Buckley B, et al. (July 2011). "Urinary incontinence in men after formal one-to-one pelvic-floor muscle training following radical prostatectomy or transurethral resection of the prostate (MAPS): two parallel randomised controlled trials". The Lancet. 378 (9788): 328–37. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60751-4. hdl:2164/2366. PMID 21741700. S2CID 31399321.

- Thüroff JW, Abrams P, Andersson KE, Artibani W, Chapple CR, Drake MJ, et al. (March 2011). "EAU guidelines on urinary incontinence". European Urology. 59 (3): 387–400. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2010.11.021. PMID 21130559. S2CID 9180421.

- "Proton Therapy Centers in the U.S." The National Association for Proton Therapy (NAPT). Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- Nag S, Beyer D, Friedland J, Grimm P, Nath R (July 1999). "American Brachytherapy Society (ABS) recommendations for transperineal permanent brachytherapy of prostate cancer". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 44 (4): 789–99. doi:10.1016/S0360-3016(99)00069-3. PMID 10386635.

- Perez CA, Hanks GE, Leibel SA, Zietman AL, Fuks Z, Lee WR (December 1993). "Localized carcinoma of the prostate (stages T1B, T1C, T2, and T3). Review of management with external beam radiation therapy". Cancer. 72 (11): 3156–73. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19931201)72:11<3156::AID-CNCR2820721106>3.0.CO;2-G. PMID 7694785. S2CID 37262788. Review.

- "Radiation Therapy for Prostate Cancer: Prostate Brachytherapy". Archived from the original on 2010-03-04. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- D'Amico AV, Manola J, Loffredo M, Renshaw AA, DellaCroce A, Kantoff PW (2004). "6-month androgen suppression plus radiation therapy vs radiation therapy alone for patients with clinically localized prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 292 (7): 821–27. doi:10.1001/jama.292.7.821. PMID 15315996.

- Hickey BE, James ML, Daly T, Soh FY, Jeffery M, et al. (Cochrane Urology Group) (September 2019). "Hypofractionation for clinically localized prostate cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (10): CD011462. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011462.pub2. PMC 6718288. PMID 31476800.

- Thompson IM, Tangen CM, Paradelo J (2009). "Adjuvant radiotherapy for pathological T3N0M0 prostate cancer significantly reduces risk of metastases and improves survival: long-term followup of a randomized clinical trial". Journal of Urology. 181 (3): 956–62. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.032. PMC 3510761. PMID 19167731.

- "Products – Augmenix". Augmenix.com. Retrieved 2012-02-16.

- Kupelian PA, Elshaikh M, Reddy CA, Zippe C, Klein EA (August 2002). "Comparison of the efficacy of local therapies for localized prostate cancer in the prostate-specific antigen era: a large single-institution experience with radical prostatectomy and external-beam radiotherapy". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 20 (16): 3376–85. doi:10.1200/JCO.2002.01.150. PMID 12177097.

- Huang H, Muscatelli S, Naslund M, Badiyan SN, Kaiser A, Siddiqui MM (Jan 2019). "Evaluation of Cancer Specific Mortality with Surgery versus Radiation as Primary Therapy for Localized High Grade Prostate Cancer in Men Younger Than 60 Years". Journal of Urology. 201 (1): 120–28. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2018.07.049. PMID 30059685. S2CID 51880099.

- Lawton CA, Won M, Pilepich MV, Asbell SO, Shipley WU, Hanks GE, et al. (September 1991). "Long-term treatment sequelae following external beam irradiation for adenocarcinoma of the prostate: analysis of RTOG studies 7506 and 7706". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 21 (4): 935–9. doi:10.1016/0360-3016(91)90732-J. PMID 1917622.

- Brenner DJ, Curtis RE, Hall EJ, Ron E (January 2000). "Second malignancies in prostate carcinoma patients after radiotherapy compared with surgery". Cancer. 88 (2): 398–406. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.385.7956. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000115)88:2<398::AID-CNCR22>3.0.CO;2-V. PMID 10640974. S2CID 7508136.

- Ahmed HU, Dickinson L, Charman S, Weir S, McCartan N, Hindley RG, et al. (December 2015). "Focal Ablation Targeted to the Index Lesion in Multifocal Localised Prostate Cancer: a Prospective Development Study". European Urology. 68 (6): 927–36. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2015.01.030. PMID 25682339.

- Karavitakis M, Ahmed HU, Abel PD, Hazell S, Winkler MH (January 2011). "Tumor focality in prostate cancer: implications for focal therapy". Nature Reviews. Clinical Oncology. 8 (1): 48–55. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.190. PMID 21116296. S2CID 32571574.

- Society of Interventional Radiology. "The Hot – And Cold – Interventional Radiology Treatments For Recurrent Prostate Cancer". www.biocompare.com. Biocompare: The buyers guide for life scientists. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Gardner TA, Koch MO (December 2005). "Prostate cancer therapy with high-intensity focused ultrasound". Clinical Genitourinary Cancer. 4 (3): 187–92. doi:10.3816/CGC.2005.n.031. PMID 16425987. S2CID 22955796.

- Pickles T, Goldenberg L, Steinhoff G (2005). "High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound for Prostate Cancer" (PDF). British Columbia Cancer Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- Barqawi AB, Crawford ED (2008). "Emerging Role of HIFU as a Noninvasive Ablative Method to Treat Localized Prostate Cancer". Oncology. 22 (2): 123–29, discussion 129, 133, 137 passim. PMID 18409659.

- Ahmed HU, Hindley RG, Dickinson L, Freeman A, Kirkham AP, Sahu M, et al. (June 2012). "Focal therapy for localised unifocal and multifocal prostate cancer: a prospective development study". The Lancet. Oncology. 13 (6): 622–32. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70121-3. PMC 3366323. PMID 22512844.

- Ahmed HU, Moore C, Lecornet E, Emberton M (May 2010). "Focal therapy in prostate cancer: determinants of success and failure". Journal of Endourology. 24 (5): 819–25. doi:10.1089/end.2009.0665. PMID 20380513.

- de Jong Y, Pinckaers JH, ten Brinck RM, Lycklama à Nijeholt AA, Dekkers OM (2014). "Urinating standing versus sitting: position is of influence in men with prostate enlargement. A systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS ONE. 9 (7): e101320. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j1320D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101320. PMC 4106761. PMID 25051345.

- Morishita S, Hamaue Y, Fukushima T, Tanaka T, Fu JB, Nakano J (January 2020). "Effect of Exercise on Mortality and Recurrence in Patients With Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Integrative Cancer Therapies. 19: 1534735420917462. doi:10.1177/1534735420917462. PMC 7273753. PMID 32476493.

- Robson M, Dawson N (June 1996). "How is androgen-dependent metastatic prostate cancer best treated?". Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 10 (3): 727–47. doi:10.1016/S0889-8588(05)70364-6. PMID 8773508. Review.

- "Immediate versus deferred treatment for advanced prostatic cancer: initial results of the Medical Research Council Trial. The Medical Research Council Prostate Cancer Working Party Investigators Group". British Journal of Urology. 79 (2): 235–46. February 1997. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.d01-6840.x. PMID 9052476.

- Sathianathen NJ, Philippou YA, Kuntz GM, Konety BR, Gupta S, Lamb AD, Dahm P, et al. (Cochrane Urology Group) (October 2018). "Taxane-based chemohormonal therapy for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (10): CD012816. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012816.pub2. PMC 6516883. PMID 30320443.

- Loblaw DA, Mendelson DS, Talcott JA, Virgo KS, Somerfield MR, Ben-Josef E, Middleton R, Porterfield H, Sharp SA, Smith TJ, Taplin ME, Vogelzang NJ, Wade JL Jr, Bennett CL, Scher HI, American Society of Clinical Oncology (July 15, 2004). "American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations for the initial hormonal management of androgen-sensitive metastatic, recurrent, or progressive prostate cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 22 (14): 2927–41. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.04.579. PMID 15184404. S2CID 20462746. (Erratum: doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.08.943)

- Attard G, Reid AH, Yap TA, Raynaud F, Dowsett M, Settatree S, et al. (October 2008). "Phase I clinical trial of a selective inhibitor of CYP17, abiraterone acetate, confirms that castration-resistant prostate cancer commonly remains hormone driven". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 26 (28): 4563–71. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9749. PMID 18645193. (Erratum: doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.43.7756)

- Warry R (July 22, 2008). "Drug for deadly prostate cancer". BBC. Retrieved 2008-07-23.

- Sathianathen NJ, Oestreich MC, Brown SJ, Gupta S, Konety BR, Dahm P, Kunath F, et al. (Cochrane Urology Group) (December 2020). "Abiraterone acetate in combination with androgen deprivation therapy compared to androgen deprivation therapy only for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD013245. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013245.pub2. PMC 8092456. PMID 33314020.

- Kunath F, Jensen K, Pinart M, Kahlmeyer A, Schmidt S, Price CL, et al. (Cochrane Urology Group) (June 2019). "Early versus deferred standard androgen suppression therapy for advanced hormone-sensitive prostate cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (6): CD003506. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003506.pub2. PMC 6564091. PMID 31194882.

- Wang, Lin; Paller, Channing J.; Hong, Hwanhee; De Felice, Anthony; Alexander, G. Caleb; Brawley, Otis (2021-03-01). "Comparison of Systemic Treatments for Metastatic Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis". JAMA Oncology. 7 (3): 412–420. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6973. ISSN 2374-2437. PMC 7809610. PMID 33443584.

- Jos van Boxtel C, Santoso B, Edwards IR (2008). Drug Benefits and Risks: International Textbook of Clinical Pharmacology. IOS Press. pp. 458–. ISBN 978-1-58603-880-9.

- Oettel M, Schillinger E (2012). Estrogens and Antiestrogens II: Pharmacology and Clinical Application of Estrogens and Antiestrogen. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 135 / 2. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 540–42. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-60107-1. ISBN 978-3-642-60107-1. S2CID 35733673.

- Coss CC, Jones A, Parke DN, Narayanan R, Barrett CM, Kearbey JD, Veverka KA, Miller DD, Morton RA, Steiner MS, Dalton JT (March 2012). "Preclinical characterization of a novel diphenyl benzamide selective ERα agonist for hormone therapy in prostate cancer". Endocrinology. 153 (3): 1070–81. doi:10.1210/en.2011-1608. PMID 22294742.

- Yu EY, Getzenberg RH, Coss CC, Gittelman MM, Keane T, Tutrone R, et al. (February 2015). "Selective estrogen receptor alpha agonist GTx-758 decreases testosterone with reduced side effects of androgen deprivation therapy in men with advanced prostate cancer". European Urology. 67 (2): 334–41. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2014.06.011. PMID 24968970.

- Hong WK, Holland JF (2010). Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine 8. PMPH-USA. pp. 753–. ISBN 978-1-60795-014-1.

- Ali Shah SI (2015). "Emerging potential of parenteral estrogen as androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer". South Asian Journal of Cancer. 4 (2): 95–97. doi:10.4103/2278-330X.155699. PMC 4418092. PMID 25992351.

- Russell N, Cheung A, Grossmann M (August 2017). "Estradiol for the mitigation of adverse effects of androgen deprivation therapy". Endocrine-Related Cancer. 24 (8): R297–R313. doi:10.1530/ERC-17-0153. PMID 28667081.

- Wibowo E, Wassersug RJ (September 2013). "The effect of estrogen on the sexual interest of castrated males: Implications to prostate cancer patients on androgen-deprivation therapy". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 87 (3): 224–38. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.01.006. PMID 23484454.

- Wibowo E, Schellhammer P, Wassersug RJ (January 2011). "Role of estrogen in normal male function: clinical implications for patients with prostate cancer on androgen deprivation therapy". Journal of Urology. 185 (1): 17–23. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.094. PMID 21074215.

- Norman G, Dean ME, Langley RE, Hodges ZC, Ritchie G, Parmar MK, Sydes MR, Abel P, Eastwood AJ (February 2008). "Parenteral oestrogen in the treatment of prostate cancer: a systematic review". British Journal of Cancer. 98 (4): 697–707. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604230. PMC 2259178. PMID 18268497.

- Lycette JL, Bland LB, Garzotto M, Beer TM (December 2006). "Parenteral estrogens for prostate cancer: can a new route of administration overcome old toxicities?". Clinical Genitourinary Cancer. 5 (3): 198–205. doi:10.3816/CGC.2006.n.037. PMID 17239273.

- Ockrim J, Lalani EN, Abel P (October 2006). "Therapy Insight: parenteral estrogen treatment for prostate cancer--a new dawn for an old therapy". Nature Clinical Practice. Oncology. 3 (10): 552–63. doi:10.1038/ncponc0602. PMID 17019433. S2CID 6847203.

- Rans K, Berghen C, Joniau S, De Meerleer G (March 2020). "Salvage Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer". Clinical Oncology. 32 (3): 156–162. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2020.01.003. PMID 32035581. S2CID 211070763.

- Tendulkar RD, Agrawal S, Gao T, Efstathiou JA, Pisansky TM, Michalski JM, et al. (October 2016). "Contemporary Update of a Multi-Institutional Predictive Nomogram for Salvage Radiotherapy After Radical Prostatectomy". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 34 (30): 3648–3654. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.67.9647. PMID 27528718.

- Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, Horti J, Pluzanska A, Chi KN, Oudard S, Theodore C, James ND, Turesson I, Rosenthal MA, Eisenberger MA, TAX 327 Investigators (October 7, 2004). "Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer". New England Journal of Medicine. 351 (15): 1502–12. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040720. PMID 15470213. S2CID 22649502.

- Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, Tchekmedyian S, Venner P, Lacombe L, Chin JL, Vinholes JJ, Goas JA, Chen B (2002). "A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of zoledronic acid in patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate carcinoma". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 94 (19): 1458–68. doi:10.1093/jnci/94.19.1458. PMID 12359855.

- Jakob T, Tesfamariam YM, Macherey S, Kuhr K, Adams A, Monsef I, et al. (Cochrane Urology Group) (December 2020). "Bisphosphonates or RANK-ligand-inhibitors for men with prostate cancer and bone metastases: a network meta-analysis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (12): CD013020. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013020.pub2. PMC 8095056. PMID 33270906.

- Ornish D, Weidner G, Fair WR, Marlin R, Pettengill EB, Raisin CJ, et al. (September 2005). "Intensive lifestyle changes may affect the progression of prostate cancer". The Journal of Urology. 174 (3): 1065–9, discussion 1069–70. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000169487.49018.73. PMID 16094059.

- Frattaroli J, Weidner G, Dnistrian AM, Kemp C, Daubenmier JJ, Marlin RO, et al. (December 2008). "Clinical events in prostate cancer lifestyle trial: results from two years of follow-up". Urology. 72 (6): 1319–23. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2008.04.050. PMID 18602144.

- Pantuck AJ, Leppert JT, Zomorodian N, Aronson W, Hong J, Barnard RJ, et al. (July 2006). "Phase II study of pomegranate juice for men with rising prostate-specific antigen following surgery or radiation for prostate cancer". Clinical Cancer Research. 12 (13): 4018–26. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2290. PMID 16818701. S2CID 7921887.

- Kumar NB, Cantor A, Allen K, Riccardi D, Besterman-Dahan K, Seigne J, et al. (May 2004). "The specific role of isoflavones in reducing prostate cancer risk". The Prostate. 59 (2): 141–7. doi:10.1002/pros.10362. PMID 15042614. S2CID 19319738.

- Yarnell E (1999). "A Naturopathic Approach to Prostate Cancer Part 2: Guidelines for Treatment and Prevention". Alternative and Complementary Therapies. 5 (6): 360–68. doi:10.1089/act.1999.5.360.

- Hall EJ (2000). Radiobiology for the Radiologist. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Williams. pp. 432–33. ISBN 978-0-06-141077-2.

- Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, et al. (January 2009). "Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT)". JAMA. 301 (1): 39–51. doi:10.1001/jama.2008.864. PMC 3682779. PMID 19066370.

- Helgason ÁR, Adolfsson J, Dickman P, Fredrikson M, Arver S, Steineck G (1996). "Waning sexual function – the most important disease-specific distress for patients with prostate cancer". British Journal of Cancer. 73 (11): 1417–21. doi:10.1038/bjc.1996.268. PMC 2074472. PMID 8645589.

- Helgason ÁR, Adolfsson J, Dickman P, Fredrikson M, Steineck G (1998). "Distress due to unwanted side-effects of prostate cancer treatment is related to impaired well-being (quality of life)". Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases. 1 (3): 128–33. doi:10.1038/sj.pcan.4500226. PMID 12496905.

- Helgason ÁR, Dickman PW, Adolfsson J, Steineck G (2001). "Emotional isolation : Prevalence and the effect on well-being among 50–80 year old prostate cancer patients". Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 35 (2): 97–101. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.549.5736. doi:10.1080/003655901750170407. PMID 11411666. S2CID 218865571.

- "Evidence Update for Clinicians: Prostate Cancer". www.pcori.org. 2018-03-30. Retrieved 2020-01-29.