Mandrake

A mandrake is the root of a plant, historically derived either from plants of the genus Mandragora found in the Mediterranean region, or from other species, such as Bryonia alba, the English mandrake, which have similar properties. The plants from which the root is obtained are also called "mandrakes". Mediterranean mandrakes are perennial herbaceous plants with ovate leaves arranged in a rosette, a thick upright root, often branched, and bell-shaped flowers followed by yellow or orange berries. They have been placed in different species by different authors. They are highly variable perennial herbaceous plants with long thick roots (often branched) and almost no stem. The leaves are borne in a basal rosette, and are variable in size and shape, with a maximum length of 45 cm (18 in). They are usually either elliptical in shape or wider towards the end (obovate), with varying degrees of hairiness.[1]

Because mandrakes contain deliriant hallucinogenic tropane alkaloids and the shape of their roots often resembles human figures, they have been associated with magic rituals throughout history, including present-day contemporary pagan traditions.[2]

The English name of the plant derives from Latin mandragora through French main-de-gloire.[3] In German, it is known as alraune ('all-rune' or 'elf-rune'), referring to the plant's folkloric ability to impart wisdom.[4] Certain sources cite the name pisdifje ('brain thief'), claiming the plant grows from the brains of dead thieves, or the droppings of those hung on the gallows.[5]

Toxicity

All species of Mandragora contain highly biologically active alkaloids, tropane alkaloids in particular. The alkaloids make the plant, in particular the root and leaves, poisonous, via anticholinergic, hallucinogenic, and hypnotic effects. Anticholinergic properties can lead to asphyxiation. Accidental poisoning is not uncommon. Ingesting mandrake root is likely to have other adverse effects such as vomiting and diarrhea. The alkaloid concentration varies between plant samples. Clinical reports of the effects of consumption of Mediterranean mandrake include severe symptoms similar to those of atropine poisoning, including blurred vision, dilation of the pupils (mydriasis), dryness of the mouth, difficulty in urinating, dizziness, headache, vomiting, blushing and a rapid heart rate (tachycardia). Hyperactivity and hallucinations occurred in the majority of patients.[6][7]

Folklore

The root is hallucinogenic and narcotic. In sufficient quantities, it induces a state of unconsciousness and was used as an anaesthetic for surgery in ancient times.[8] In the past, juice from the finely grated root was applied externally to relieve rheumatic pains.[8] It was used internally to treat melancholy, convulsions, and mania.[8] When taken internally in large doses it was said to excite delirium and madness.[8]

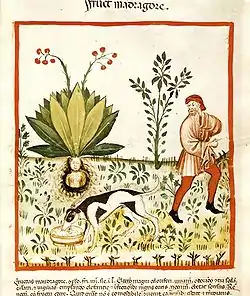

In the past, mandrake was often made into amulets which were believed to bring good fortune, cure sterility, etc. In one superstition, people who pull up this root will be condemned to hell, and the mandrake root would scream and cry as it was pulled from the ground, killing anyone who heard it.[2] Therefore, in the past, people have tied the roots to the bodies of animals and then used these animals to pull the roots from the soil.[2] This folklore reference is integrated into part of the portrayal of the fictional mandrake described in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.

The ancient Greeks burned mandrake as incense.[9]

In the Bible

Two references to דודאים (duda'im, plural; singular דודא duda)—literally meaning "love plants"—occur in the Jewish scriptures. The Septuagint translates דודאים as μανδραγόρας (mandragóras), and the Vulgate follows the Septuagint. A number of later translations into different languages follow Septuagint (and Vulgate) and use mandrake as the plant as the proper meaning in both the Book of Genesis 30:14–16 and Song of Songs 7:12-13. Others follow the example of the Luther Bible and provide a more literal translation.

In Genesis 30:14, Reuben, the eldest son of Jacob and Leah, finds mandrakes in a field. Rachel, Jacob's infertile second wife and Leah's sister, is desirous of the דודאים and barters with Leah for them. The trade offered by Rachel is for Leah to spend that night in Jacob's bed in exchange for Leah's דודאים. Leah gives away the plants to her barren sister, but soon after this (Genesis 30:14–22), Leah, who had previously had four sons but had been infertile for a long while, became pregnant once more and in time gave birth to two more sons, Issachar and Zebulun, and a daughter, Dinah. Only years after this episode of her asking for the mandrakes did Rachel manage to become pregnant.

And Reuben went in the days of wheat harvest, and found mandrakes in the field, and brought them unto his mother Leah. Then Rachel said to Leah, Give me, I pray thee, of thy son's mandrakes. And she said unto her, Is it a small matter that thou hast taken my husband? and wouldest thou take away my son's mandrakes also? And Rachel said, Therefore he shall lie with thee to night for thy son's mandrakes. And Jacob came out of the field in the evening, and Leah went out to meet him, and said, Thou must come in unto me; for surely I have hired thee with my son's mandrakes. And he lay with her that night.

Sir Thomas Browne, in Pseudodoxia Epidemica, however, suggests the duda'im of Genesis 30:14 refers only to the opium poppy (as a metaphor describing a woman's breasts.)

The final verses of Chapter 7 of Song of Songs (Song of Songs 7:12–13), mention the plant once again:

נַשְׁכִּ֙ימָה֙ לַכְּרָמִ֔ים נִרְאֶ֞ה אִם פָּֽרְחָ֤ה הַגֶּ֙פֶן֙ פִּתַּ֣ח הַסְּמָדַ֔ר הֵנֵ֖צוּ הָרִמֹּונִ֑ים שָׁ֛ם אֶתֵּ֥ן אֶת־דֹּדַ֖י לָֽךְ׃ הַֽדּוּדָאִ֣ים נָֽתְנוּ-רֵ֗יחַ וְעַל-פְּתָחֵ֙ינוּ֙ כָּל-מְגָדִ֔ים חֲדָשִׁ֖ים גַּם-יְשָׁנִ֑ים דּוֹדִ֖י צָפַ֥נְתִּי לָֽךְ:

Let us get up early to the vineyards; let us see if the vine flourish, whether the tender grape appear, and the pomegranates bud forth: there will I give thee my loves. The mandrakes give a smell, and at our gates are all manner of pleasant fruits, new and old, which I have laid up for thee, O my beloved.

Magic and witchcraft

According to the legend, when the root is dug up, it screams and kills all who hear it. Literature includes complex directions for harvesting a mandrake root in relative safety. For example, Josephus (circa 37–100 AD) of Jerusalem gives the following directions for pulling it up:

A furrow must be dug around the root until its lower part is exposed, then a dog is tied to it, after which the person tying the dog must get away. The dog then endeavours to follow him, and so easily pulls up the root, but dies suddenly instead of his master. After this, the root can be handled without fear.[12]

An excerpt from Transcendental Magic: Its Doctrine and Ritual by nineteenth-century occultist and ceremonial magician Eliphas Levi, suggests the plant might hint at mankind's "terrestrial origin:"

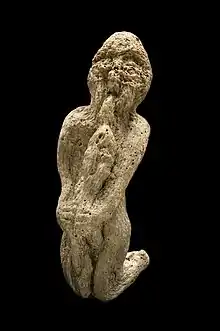

The natural mandragore is a filamentous root which, more or less, presents as a whole either the figure of a man, or that of the virile members. It is slightly narcotic, and an aphrodisiacal virtue was ascribed to it by the ancients, who represented it as being sought by Thessalian sorcerers for the composition of philtres. Is this root the umbilical vestige of our terrestrial origin? We dare not seriously affirm it, but all the same it is certain that man came out of the slime of the earth, and his first appearance must have been in the form of a rough sketch. The analogies of nature make this notion necessarily admissible, at least as a possibility. The first men were, in this case, a family of gigantic, sensitive mandragores, animated by the sun, who rooted themselves up from the earth; this assumption not only does not exclude, but, on the contrary, positively supposes, creative will and the providential co-operation of a first cause, which we have REASON to call GOD. Some alchemists, impressed by this idea, speculated on the culture of the mandragore, and experimented in the artificial reproduction of a soil sufficiently fruitful and a sun sufficiently active to humanise the said root, and thus create men without the concurrence of the female. Others, who regarded humanity as the synthesis of animals, despaired about vitalising the mandragore, but they crossed monstrous pairs and projected human seed into animal earth, only for the production of shameful crimes and barren deformities.[13]

The following is taken from Jean-Baptiste Pitois' The History and Practice of Magic, and explains a ritual for creating a mandrake:

Would you like to make a Mandragora, as powerful as the homunculus (little man in a bottle) so praised by Paracelsus? Then find a root of the plant called bryony. Take it out of the ground on a Monday (the day of the moon), a little time after the vernal equinox. Cut off the ends of the root and bury it at night in some country churchyard in a dead man's grave. For 30 days, water it with cow's milk in which three bats have been drowned. When the 31st day arrives, take out the root in the middle of the night and dry it in an oven heated with branches of verbena; then wrap it up in a piece of a dead man's winding-sheet and carry it with you everywhere.[14]

In Medieval times, mandrake was considered a key ingredient in a multitude of witches' flying ointment recipes as well as a primary component of magical potions and brews.[15] These were entheogenic preparations used in European witchcraft for their mind-altering and hallucinogenic effects.[16] Starting in the Late Middle Ages and thereafter, some believed that witches applied these ointments or ingested these potions to help them fly to gatherings with other witches, meet with the Devil, or to experience bacchanalian carousal.[17][18]

Romani people use mandrake as a love amulet.[19]

References

- Ungricht, Stefan; Knapp, Sandra & Press, John R. (1998). "A revision of the genus Mandragora (Solanaceae)". Bulletin of the Natural History Museum, Botany Series. 28 (1): 17–40. Retrieved 2015-03-31.

- John Gerard (1597). "Herball, Generall Historie of Plants". Claude Moore Health Sciences Library. Archived from the original on 2012-09-01. Retrieved 2015-08-03.

- Wedgwood, Hensleigh (1855). "On False Etymologies". Transactions of the Philological Society (6): 67.

- "Alraune (Kulturgeschichte)", Wikipedia (in German), 2023-03-05, retrieved 2023-03-06

- Leland, Charles Godfrey (1892). Etruscan Roman Remains in Popular Tradition. T. F. Unwin.

- Jiménez-Mejías, M.E.; Montaño-Díaz, M.; López Pardo, F.; Campos Jiménez, E.; Martín Cordero, M.C.; Ayuso González, M.J. & González de la Puente, M.A. (1990-11-24). "Intoxicación atropínica por Mandragora autumnalis: descripción de quince casos [Atropine poisoning by Mandragora autumnalis: a report of 15 cases]". Medicina Clínica. 95 (18): 689–692. PMID 2087109.

- Piccillo, Giovita A.; Mondati, Enrico G. M. & Moro, Paola A. (2002). "Six clinical cases of Mandragora autumnalis poisoning: diagnosis and treatment". European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 9 (4): 342–347. doi:10.1097/00063110-200212000-00010. PMID 12501035.

- A Modern Herbal, first published in 1931, by Mrs. M. Grieve, contains Medicinal, Culinary, Cosmetic and Economic Properties, Cultivation and Folk-Lore.

- Carod-Artal, F. J. (2013). "Psychoactive plants in ancient Greece". nah.sen.es. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- "Genesis 30:14–16 (King James Version)". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- "Song of Songs 7:12–13 (King James Version)". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- James Hastings (October 2004). A Dictionary of the Bible: Volume III: (Part I: Kir -- Nympha). University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 978-1-4102-1726-4. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- pp. 312, by Eliphas Levi. 1896

- pp. 402-403, by Paul Christian. 1963

- Hansen, Harold A. The Witch's Garden pub. Unity Press 1978 ISBN 978-0913300473

- Raetsch, Ch. (2005). The encyclopedia of psychoactive plants: ethnopharmacology and its applications. US: Park Street Press. pp. 277–282.

- Peters, Edward (2001). "Sorcerer and Witch". In Jolly, Karen Louise; Raudvere, Catharina; et al. (eds.). Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: The Middle Ages. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 233–37. ISBN 978-0-485-89003-7.

- Hansen, Harold A. The Witch's Garden pub. Unity Press 1978 ISBN 978-0913300473

- Gerina Dunwich. Herbal Magick: A Guide to Herbal Enchantments, Folklore, and Divination.

Further reading

- Heiser, Charles B. Jr (1969). Nightshades, The Paradoxical Plant, 131-136. W. H. Freeman & Co. SBN 7167 0672-5.

- Thompson, C. J. S. (reprint 1968). The Mystic Mandrake. University Books.

- Muraresku, Brian C. (2020). The Immortality Key: The Secret History of the Religion with No Name. Macmillan USA. ISBN 978-1250207142

External links

- Erowid Mandrake Vault

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Mandragora in Wildflowers of Israel