Hamlet

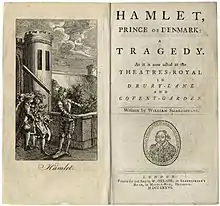

The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, often shortened to Hamlet (/ˈhæmlɪt/), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts Prince Hamlet and his attempts to exact revenge against his uncle, Claudius, who has murdered Hamlet's father in order to seize his throne and marry Hamlet's mother.

| Hamlet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Written by | William Shakespeare |

| Characters | |

| Original language | Early Modern English |

| Genre | Shakespearean tragedy |

| Setting | Denmark |

Hamlet is considered among the "most powerful and influential tragedies in the English language", with a story capable of "seemingly endless retelling and adaptation by others".[1]

There are many works that have been pointed to as possible sources for Shakespeare's play—from ancient Greek tragedies to Elizabethan plays. The editors of the Arden Shakespeare question the idea of "source hunting", pointing out that it presupposes that authors always require ideas from other works for their own, and suggests that no author can have an original idea or be an originator. When Shakespeare wrote, there were many stories about sons avenging the murder of their fathers, and many about clever avenging sons pretending to be foolish in order to outsmart their foes. This would include the story of the ancient Roman, Lucius Junius Brutus, which Shakespeare apparently knew, as well as the story of Amleth, which was preserved in Latin by 13th-century chronicler Saxo Grammaticus in his Gesta Danorum, and printed in Paris in 1514. The Amleth story was subsequently adapted and then published in French in 1570 by the 16th-century scholar François de Belleforest. It has a number of plot elements and major characters in common with Shakespeare's Hamlet, and lacks others that are found in Shakespeare. Belleforest's story was first published in English in 1608, after Hamlet had been written, though it's possible that Shakespeare had encountered it in the French-language version.[2]

Three different early versions of the play are extant: the First Quarto (Q1, 1603); the Second Quarto (Q2, 1604); and the First Folio (F1, 1623). Each version includes lines and passages missing from the others.[3]

Characters

- Hamlet – son of the late king and nephew of the present king, Claudius

- Claudius – King of Denmark, Hamlet's uncle and brother to the former king

- Gertrude – Queen of Denmark and Hamlet's mother

- Polonius – chief counsellor to the king

- Ophelia – Polonius's daughter

- Horatio – friend of Hamlet

- Laertes – Polonius's son

- Voltimand and Cornelius – courtiers

- Rosencrantz and Guildenstern – courtiers, friends of Hamlet

- Osric – a courtier

- Marcellus – an officer

- Barnardo – an officer

- Francisco – a soldier

- Reynaldo – Polonius's servant

- Ghost – the ghost of Hamlet's father

- Fortinbras – prince of Norway

- Gravediggers – a pair of sextons

- Player King, Player Queen, Lucianus, etc. – players

Plot

Act I

Prince Hamlet of Denmark is the son of the recently deceased King Hamlet, and nephew of King Claudius, his father's brother and successor. Claudius hastily married King Hamlet's widow, Gertrude, Hamlet's mother, and took the throne for himself. Denmark has a long-standing feud with neighbouring Norway, in which King Hamlet slew King Fortinbras of Norway in a battle some years ago. Although Denmark defeated Norway and the Norwegian throne fell to King Fortinbras's infirm brother, Denmark fears that an invasion led by the dead Norwegian king's son, Prince Fortinbras, is imminent.

On a cold night on the ramparts of Elsinore, the Danish royal castle, the sentries Bernardo and Marcellus discuss a ghost resembling the late King Hamlet which they have recently seen, and bring Prince Hamlet's friend Horatio as a witness. After the ghost appears again, the three vow to tell Prince Hamlet what they have witnessed.

The court gathers the next day, and King Claudius and Queen Gertrude discuss affairs of state with their elderly adviser Polonius. Claudius grants permission for Polonius's son Laertes to return to school in France, and he sends envoys to inform the King of Norway about Fortinbras. Claudius also questions Hamlet regarding his continuing to grieve for his father, and forbids him to return to his university in Wittenberg. After the court exits, Hamlet despairs of his father's death and his mother's hasty remarriage. Learning of the ghost from Horatio, Hamlet resolves to see it himself.

As Polonius's son Laertes prepares to depart for France, Polonius offers him advice that culminates in the maxim "to thine own self be true."[5] Polonius's daughter, Ophelia, admits her interest in Hamlet, but Laertes warns her against seeking the prince's attention, and Polonius orders her to reject his advances. That night on the rampart, the ghost appears to Hamlet, tells the prince that he was murdered by Claudius, and demands that Hamlet avenge the murder. Hamlet agrees, and the ghost vanishes. The prince confides to Horatio and the sentries that from now on he plans to "put an antic disposition on", or act as though he has gone mad. Hamlet forces them to swear to keep his plans for revenge secret; however, he remains uncertain of the ghost's reliability.

Act II

Ophelia rushes to her father, telling him that Hamlet arrived at her door the prior night half-undressed and behaving erratically. Polonius blames love for Hamlet's madness and resolves to inform Claudius and Gertrude. As he enters to do so, the king and queen are welcoming Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, two student acquaintances of Hamlet, to Elsinore. The royal couple has requested that the two students investigate the cause of Hamlet's mood and behaviour. Additional news requires that Polonius wait to be heard: messengers from Norway inform Claudius that the king of Norway has rebuked Prince Fortinbras for attempting to re-fight his father's battles. The forces that Fortinbras had conscripted to march against Denmark will instead be sent against Poland, though they will pass through Danish territory to get there.

Polonius tells Claudius and Gertrude his theory regarding Hamlet's behaviour, and then speaks to Hamlet in a hall of the castle to try to learn more. Hamlet feigns madness and subtly insults Polonius all the while. When Rosencrantz and Guildenstern arrive, Hamlet greets his "friends" warmly but quickly discerns that they are there to spy on him for Claudius. Hamlet admits that he is upset at his situation but refuses to give the true reason, instead remarking "What a piece of work is a man". Rosencrantz and Guildenstern tell Hamlet that they have brought along a troupe of actors that they met while travelling to Elsinore. Hamlet, after welcoming the actors and dismissing his friends-turned-spies, asks them to deliver a soliloquy about the death of King Priam and Queen Hecuba at the climax of the Trojan War. Hamlet then asks the actors to stage The Murder of Gonzago, a play featuring a death in the style of his father's murder. Hamlet intends to study Claudius's reaction to the play, and thereby determine the truth of the ghost's story of Claudius's guilt.

Act III

Polonius forces Ophelia to return Hamlet's love letters to the prince while he and Claudius secretly watch in order to evaluate Hamlet's reaction. Hamlet is walking alone in the hall as the King and Polonius await Ophelia's entrance. Hamlet muses on thoughts of life versus death. When Ophelia enters and tries to return Hamlet's things, Hamlet accuses her of immodesty and cries "get thee to a nunnery", though it is unclear whether this, too, is a show of madness or genuine distress. His reaction convinces Claudius that Hamlet is not mad for love. Shortly thereafter, the court assembles to watch the play Hamlet has commissioned. After seeing the Player King murdered by his rival pouring poison in his ear, Claudius abruptly rises and runs from the room; for Hamlet, this is proof of his uncle's guilt.

Gertrude summons Hamlet to her chamber to demand an explanation. Meanwhile, Claudius talks to himself about the impossibility of repenting, since he still has possession of his ill-gotten goods: his brother's crown and wife. He sinks to his knees. Hamlet, on his way to visit his mother, sneaks up behind him but does not kill him, reasoning that killing Claudius while he is praying will send him straight to heaven while his father's ghost is stuck in purgatory. In the queen's bedchamber, Hamlet and Gertrude fight bitterly. Polonius, spying on the conversation from behind a tapestry, calls for help as Gertrude, believing Hamlet wants to kill her, calls out for help herself.

Hamlet, believing it is Claudius, stabs wildly, killing Polonius, but he pulls aside the curtain and sees his mistake. In a rage, Hamlet brutally insults his mother for her apparent ignorance of Claudius's villainy, but the ghost enters and reprimands Hamlet for his inaction and harsh words. Unable to see or hear the ghost herself, Gertrude takes Hamlet's conversation with it as further evidence of madness. After begging the queen to stop sleeping with Claudius, Hamlet leaves, dragging Polonius's corpse away.

Act IV

Hamlet jokes with Claudius about where he has hidden Polonius's body, and the king, fearing for his life, sends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to accompany Hamlet to England with a sealed letter to the English king requesting that Hamlet be executed immediately.

Unhinged by grief at Polonius's death, Ophelia wanders Elsinore. Laertes arrives back from France, enraged by his father's death and his sister's madness. Claudius convinces Laertes that Hamlet is solely responsible, but a letter soon arrives indicating that Hamlet has returned to Denmark, foiling Claudius's plan. Claudius switches tactics, proposing a fencing match between Laertes and Hamlet to settle their differences. Laertes will be given a poison-tipped foil, and, if that fails, Claudius will offer Hamlet poisoned wine as a congratulation. Gertrude interrupts to report that Ophelia has drowned, though it is unclear whether it was suicide or an accident caused by her madness.

Act V

Horatio has received a letter from Hamlet, explaining that the prince escaped by negotiating with pirates who attempted to attack his England-bound ship, and the friends reunite offstage. Two gravediggers discuss Ophelia's apparent suicide while digging her grave. Hamlet arrives with Horatio and banters with one of the gravediggers, who unearths the skull of a jester from Hamlet's childhood, Yorick. Hamlet picks up the skull, saying "Alas, poor Yorick" as he contemplates mortality. Ophelia's funeral procession approaches, led by Laertes. Hamlet and Horatio initially hide, but when Hamlet realizes that Ophelia is the one being buried, he reveals himself, proclaiming his love for her. Laertes and Hamlet fight by Ophelia's graveside, but the brawl is broken up.

Back at Elsinore, Hamlet explains to Horatio that he had discovered Claudius's letter with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern's belongings and replaced it with a forged copy indicating that his former friends should be killed instead. A foppish courtier, Osric, interrupts the conversation to deliver the fencing challenge to Hamlet. Hamlet, despite Horatio's pleas, accepts it. Hamlet does well at first, leading the match by two hits to none, and Gertrude raises a toast to him using the poisoned glass of wine Claudius had set aside for Hamlet. Claudius tries to stop her but is too late: she drinks, and Laertes realizes the plot will be revealed. Laertes slashes Hamlet with his poisoned blade. In the ensuing scuffle, they switch weapons, and Hamlet wounds Laertes with his own poisoned sword. Gertrude collapses and, claiming she has been poisoned, dies. In his dying moments, Laertes reconciles with Hamlet and reveals Claudius's plan. Hamlet rushes at Claudius and kills him. As the poison takes effect, Hamlet, hearing that Fortinbras is marching through the area, names the Norwegian prince as his successor. Horatio, distraught at the thought of being the last survivor and living whilst Hamlet does not, says he will commit suicide by drinking the dregs of Gertrude's poisoned wine, but Hamlet begs him to live on and tell his story. Hamlet dies in Horatio's arms, proclaiming "the rest is silence". Fortinbras, who was ostensibly marching towards Poland with his army, arrives at the palace, along with an English ambassador bringing news of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern's deaths. Horatio promises to recount the full story of what happened, and Fortinbras, seeing the entire Danish royal family dead, takes the crown for himself and orders a military funeral to honour Hamlet.

Sources

Hamlet-like legends are so widely found (for example in Italy, Spain, Scandinavia, Byzantium, and Arabia) that the core "hero-as-fool" theme is possibly Indo-European in origin.[7] Several ancient written precursors to Hamlet can be identified. The first is the anonymous Scandinavian Saga of Hrolf Kraki. In this, the murdered king has two sons—Hroar and Helgi—who spend most of the story in disguise, under false names, rather than feigning madness, in a sequence of events that differs from Shakespeare's.[8] The second is the Roman legend of Brutus, recorded in two separate Latin works. Its hero, Lucius ("shining, light"), changes his name and persona to Brutus ("dull, stupid"), playing the role of a fool to avoid the fate of his father and brothers, and eventually slaying his family's killer, King Tarquinius. A 17th-century Nordic scholar, Torfaeus, compared the Icelandic hero Amlóði (Amlodi) and the hero Prince Ambales (from the Ambales Saga) to Shakespeare's Hamlet. Similarities include the prince's feigned madness, his accidental killing of the king's counsellor in his mother's bedroom, and the eventual slaying of his uncle.[9]

Many of the earlier legendary elements are interwoven in the 13th-century "Life of Amleth" (Latin: Vita Amlethi) by Saxo Grammaticus, part of Gesta Danorum.[10] Written in Latin, it reflects classical Roman concepts of virtue and heroism, and was widely available in Shakespeare's day.[11] Significant parallels include the prince feigning madness, his mother's hasty marriage to the usurper, the prince killing a hidden spy, and the prince substituting the execution of two retainers for his own. A reasonably faithful version of Saxo's story was translated into French in 1570 by François de Belleforest, in his Histoires tragiques.[12] Belleforest embellished Saxo's text substantially, almost doubling its length, and introduced the hero's melancholy.[13]

According to one theory, Shakespeare's main source may be an earlier play—now lost—known today as the Ur-Hamlet. Possibly written by Thomas Kyd or by Shakespeare, the Ur-Hamlet would have existed by 1589, and would have incorporated a ghost.[14] Shakespeare's company, the Chamberlain's Men, may have purchased that play and performed a version for some time, which Shakespeare reworked.[15] However, no copy of the Ur-Hamlet has survived, and it is impossible to compare its language and style with the known works of any of its putative authors. In 1936 Andrew Cairncross suggested that, until more becomes known, it may be assumed that Shakespeare wrote the Ur-Hamlet.[16] Eric Sams lists reasons for supporting Shakespeare’s authorship.[17] Harold Jenkins considers that there are no grounds for thinking that the Ur-Hamlet is an early work by Shakespeare, which he then rewrote.[18]

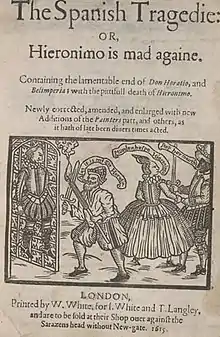

It is not known whether the Ur-Hamlet, Belleforest, Saxo, or Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy were sources for Shakespeare's Hamlet. However, elements of Belleforest's version which are not in Saxo's story do appear in Shakespeare's play.[19]

Most scholars reject the idea that Hamlet is in any way connected with Shakespeare's only son, Hamnet Shakespeare, who died in 1596 at age eleven. Conventional wisdom holds that Hamlet is too obviously connected to legend, and the name Hamnet was quite popular at the time.[20] However, Stephen Greenblatt has argued that the coincidence of the names and Shakespeare's grief for the loss of his son may lie at the heart of the tragedy. He notes that the name of Hamnet Sadler, the Stratford neighbour after whom Hamnet was named, was often written as Hamlet Sadler and that, in the loose orthography of the time, the names were virtually interchangeable.[21][22]

Scholars have often speculated that Hamlet's Polonius might have been inspired by William Cecil (Lord Burghley)—Lord High Treasurer and chief counsellor to Queen Elizabeth I. E. K. Chambers suggested Polonius's advice to Laertes may have echoed Burghley's to his son Robert Cecil.[23] John Dover Wilson thought it almost certain that the figure of Polonius caricatured Burghley.[24] A. L. Rowse speculated that Polonius's tedious verbosity might have resembled Burghley's.[25] Lilian Winstanley thought the name Corambis (in the First Quarto) did suggest Cecil and Burghley.[26] Harold Jenkins considers the idea of Polonius as a caricature of Burghley to be conjecture, perhaps based on the similar role they each played at court, and perhaps also based on the similarity between Burghley addressing his Ten Precepts to his son, and Polonius offering "precepts" to his son, Laertes.[27] Jenkins suggests that any personal satire may be found in the name "Polonius", which might point to a Polish or Polonian connection.[28] G. R. Hibbard hypothesised that differences in names (Corambis/Polonius:Montano/Raynoldo) between the First Quarto and other editions might reflect a desire not to offend scholars at Oxford University. (Robert Pullen, was the founder of Oxford University, and John Rainolds, was the President of Corpus Christi College.)[29]

Date

"Any dating of Hamlet must be tentative", states the New Cambridge editor, Phillip Edwards. MacCary suggests 1599 or 1600;[30] James Shapiro offers late 1600 or early 1601;[31] Wells and Taylor suggest that the play was written in 1600 and revised later;[32] the New Cambridge editor settles on mid-1601;[33] the New Swan Shakespeare Advanced Series editor agrees with 1601;[34] Thompson and Taylor, tentatively ("according to whether one is the more persuaded by Jenkins or by Honigmann") suggest a terminus ad quem of either Spring 1601 or sometime in 1600.[35]

The earliest date estimate relies on Hamlet's frequent allusions to Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, itself dated to mid-1599.[36][37] The latest date estimate is based on an entry, of 26 July 1602, in the Register of the Stationers' Company, indicating that Hamlet was "latelie Acted by the Lo: Chamberleyne his servantes".

In 1598, Francis Meres published his Palladis Tamia, a survey of English literature from Chaucer to its present day, within which twelve of Shakespeare's plays are named. Hamlet is not among them, suggesting that it had not yet been written. As Hamlet was very popular, Bernard Lott, the series editor of New Swan, believes it "unlikely that he [Meres] would have overlooked ... so significant a piece".[34]

The phrase "little eyases"[38] in the First Folio (F1) may allude to the Children of the Chapel, whose popularity in London forced the Globe company into provincial touring.[39] This became known as the War of the Theatres, and supports a 1601 dating.[34] Katherine Duncan-Jones accepts a 1600–01 attribution for the date Hamlet was written, but notes that the Lord Chamberlain's Men, playing Hamlet in the 3000-capacity Globe, were unlikely to be put to any disadvantage by an audience of "barely one hundred" for the Children of the Chapel's equivalent play, Antonio's Revenge; she believes that Shakespeare, confident in the superiority of his own work, was making a playful and charitable allusion to his friend John Marston's very similar piece.[40]

A contemporary of Shakespeare's, Gabriel Harvey, wrote a marginal note in his copy of the 1598 edition of Chaucer's works, which some scholars use as dating evidence. Harvey's note says that "the wiser sort" enjoy Hamlet, and implies that the Earl of Essex—executed in February 1601 for rebellion—was still alive. Other scholars consider this inconclusive. Edwards, for example, concludes that the "sense of time is so confused in Harvey's note that it is really of little use in trying to date Hamlet". This is because the same note also refers to Spenser and Watson as if they were still alive ("our flourishing metricians"), but also mentions "Owen's new epigrams", published in 1607.[41]

Texts

Three early editions of the text, each different, have survived, making attempts to establish a single "authentic" text problematic.[42][43][44]

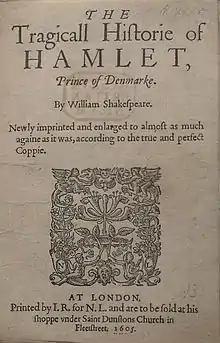

- First Quarto (Q1): In 1603 the booksellers Nicholas Ling and John Trundell published, and Valentine Simmes printed, the so-called "bad" first quarto, under the name The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet Prince of Denmarke. Q1 contains just over half of the text of the later second quarto.

- Second Quarto (Q2): In 1604 Nicholas Ling published, and James Roberts printed, the second quarto, under the same name as the first. Some copies are dated 1605, which may indicate a second impression; consequently, Q2 is often dated "1604/5". Q2 is the longest early edition, although it omits about 77 lines found in F1[45] (most likely to avoid offending James I's queen, Anne of Denmark).[46]

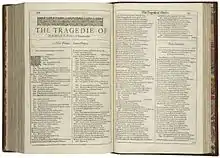

- First Folio (F1): In 1623 Edward Blount and William and Isaac Jaggard published The Tragedie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke in the First Folio, the first edition of Shakespeare's Complete Works. [47]

This list does not include three additional early texts, John Smethwick's Q3, Q4, and Q5 (1611–37), which are regarded as reprints of Q2 with some alterations.[47]

Early editors of Shakespeare's works, beginning with Nicholas Rowe (1709) and Lewis Theobald (1733), combined material from the two earliest sources of Hamlet available at the time, Q2 and F1. Each text contains material that the other lacks, with many minor differences in wording: scarcely 200 lines are identical in the two. Editors have combined them in an effort to create one "inclusive" text that reflects an imagined "ideal" of Shakespeare's original. Theobald's version became standard for a long time,[48] and his "full text" approach continues to influence editorial practice to the present day. Some contemporary scholarship, however, discounts this approach, instead considering "an authentic Hamlet an unrealisable ideal. ... there are texts of this play but no text".[49] The 2006 publication by Arden Shakespeare of different Hamlet texts in different volumes is perhaps evidence of this shifting focus and emphasis.[lower-alpha 1] Other editors have continued to argue the need for well-edited editions taking material from all versions of the play. Colin Burrow has argued that "most of us should read a text that is made up by conflating all three versions ... it's about as likely that Shakespeare wrote: "To be or not to be, ay, there's the point" [in Q1], as that he wrote the works of Francis Bacon. I suspect most people just won't want to read a three-text play ... [multi-text editions are] a version of the play that is out of touch with the needs of a wider public."[54]

Traditionally, editors of Shakespeare's plays have divided them into five acts. None of the early texts of Hamlet, however, were arranged this way, and the play's division into acts and scenes derives from a 1676 quarto. Modern editors generally follow this traditional division but consider it unsatisfactory; for example, after Hamlet drags Polonius's body out of Gertrude's bedchamber, there is an act-break[55] after which the action appears to continue uninterrupted.[56]

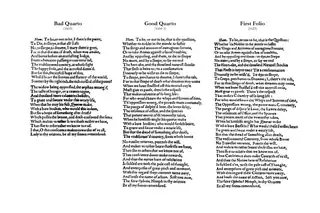

Q1 was discovered in 1823. Only two copies are extant. According to Jenkins, "The unauthorized nature of this quarto is matched by the corruption of its text."[57] Yet Q1 has value: it contains stage directions (such as Ophelia entering with a lute and her hair down) that reveal actual stage practices in a way that Q2 and F1 do not; it contains an entire scene (usually labelled 4.6)[58] that does not appear in either Q2 or F1; and it is useful for comparison with the later editions. The major deficiency of Q1 is in the language: particularly noticeable in the opening lines of the famous "To be, or not to be" soliloquy: "To be, or not to be, aye there's the point. / To die, to sleep, is that all? Aye all: / No, to sleep, to dream, aye marry there it goes." However, the scene order is more coherent, without the problems of Q2 and F1 of Hamlet seeming to resolve something in one scene and enter the next drowning in indecision. New Cambridge editor Kathleen Irace has noted that "Q1's more linear plot design is certainly easier [...] to follow [...] but the simplicity of the Q1 plot arrangement eliminates the alternating plot elements that correspond to Hamlet's shifts in mood."[59]

Q1 is considerably shorter than Q2 or F1 and may be a memorial reconstruction of the play as Shakespeare's company performed it, by an actor who played a minor role (most likely Marcellus).[60] Scholars disagree whether the reconstruction was pirated or authorised. It is suggested by Irace that Q1 is an abridged version intended especially for travelling productions, thus the question of length may be considered as separate from issues of poor textual quality.[53][61] Editing Q1 thus poses problems in whether or not to "correct" differences from Q2 and F. Irace, in her introduction to Q1, wrote that "I have avoided as many other alterations as possible, because the differences...are especially intriguing...I have recorded a selection of Q2/F readings in the collation." The idea that Q1 is not riddled with error but is instead eminently fit for the stage has led to at least 28 different Q1 productions since 1881.[62] Other productions have used the probably superior Q2 and Folio texts, but used Q1's running order, in particular moving the to be or not to be soliloquy earlier.[63] Developing this, some editors such as Jonathan Bate have argued that Q2 may represent "a 'reading' text as opposed to a 'performance' one" of Hamlet, analogous to how modern films released on disc may include deleted scenes: an edition containing all of Shakespeare's material for the play for the pleasure of readers, so not representing the play as it would have been staged.[64][65]

Analysis and criticism

Critical history

From the early 17th century, the play was famous for its ghost and vivid dramatisation of melancholy and insanity, leading to a procession of mad courtiers and ladies in Jacobean and Caroline drama.[66][67] Though it remained popular with mass audiences, late 17th-century Restoration critics saw Hamlet as primitive and disapproved of its lack of unity and decorum.[68][69] This view changed drastically in the 18th century, when critics regarded Hamlet as a hero—a pure, brilliant young man thrust into unfortunate circumstances.[70] By the mid-18th century, however, the advent of Gothic literature brought psychological and mystical readings, returning madness and the ghost to the forefront.[71] Not until the late 18th century did critics and performers begin to view Hamlet as confusing and inconsistent. Before then, he was either mad, or not; either a hero, or not; with no in-betweens.[72] These developments represented a fundamental change in literary criticism, which came to focus more on character and less on plot.[73] By the 19th century, Romantic critics valued Hamlet for its internal, individual conflict reflecting the strong contemporary emphasis on internal struggles and inner character in general.[74] Then too, critics started to focus on Hamlet's delay as a character trait, rather than a plot device.[73] This focus on character and internal struggle continued into the 20th century, when criticism branched in several directions, discussed in context and interpretation below.

Dramatic structure

Modern editors have divided the play into five acts, and each act into scenes. The First Folio marks the first two acts only. The quartos do not have such divisions. The division into five acts follows Seneca, who in his plays, regularized the way ancient Greek tragedies contain five episodes, which are separated by four choral odes. In Hamlet the development of the plot or the action are determined by the unfolding of Hamlet's character. The soliloquies do not interrupt the plot, instead they are highlights of each block of action. The plot is the developing revelation of Hamlet's view of what is "rotten in the state of Denmark." The action of the play is driven forward in dialogue; but in the soliloquies time and action stop, the meaning of action is questioned, fog of illusion is broached, and truths are exposed.

The contrast between appearance and reality is a significant theme. Hamlet is presented with an image, and then interprets its deeper or darker meaning. Examples begin with Hamlet questioning the reality of the ghost. It continues with Hamlet's taking on an "antic disposition" in order to appear mad, though he is not. The contrast (appearance and reality) is also expressed in several "spying scenes": Act two begins with Polonius sending Reynaldo to spy on his son, Laertes. Claudius and Polonius spy on Ophelia as she meets with Hamlet. In act two, Claudius asks Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to spy on Hamlet. Similarly, the play-within-a-play is used by Hamlet to reveal his step-father's hidden nature.

There is no subplot, but the play presents the affairs of the courtier Polonius, his daughter, Ophelia, and his son, Laertes—who variously deal with madness, love and the death of a father in ways that contrast with Hamlet's. The graveyard scene eases tension prior to the catastrophe, and, as Hamlet holds the skull, it is shown that Hamlet no longer fears damnation in the afterlife, and accepts that there is a "divinity that shapes our ends".[75]

Hamlet's enquiring mind has been open to all kinds of ideas, but in act five he has decided on a plan, and in a dialogue with Horatio he seems to answer his two earlier soliloquies on suicide: "We defy augury. There is special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, 'tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all. Since no man, of aught he leaves, knows aught, what is't to leave betimes."[76][77]

Length

The First Quarto (1603) text of Hamlet contains 15,983 words, the Second Quarto (1604) contains 28,628 words, and the First Folio (1623) contains 27,602 words. Counting the number of lines varies between editions, partly because prose sections in the play may be formatted with varied lengths.[78] Editions of Hamlet that are created by conflating the texts of the Second Quarto and the Folio are said to have approximately 3,900 lines;[79] the number of lines varies between those editions based on formatting the prose sections, counting methods, and how the editors have joined the texts together.[80] Hamlet is by far the longest play that Shakespeare wrote, and one of the longest plays in the Western canon. It might require more than four hours to stage;[81] a typical Elizabethan play would need two to three hours.[82] It is speculated that the because of the considerable length of Q2 and F1, there was an expectation that those texts would be abridged for performance, or that Q2 and F1 may have been aimed at a reading audience.[83]

That Q1 is so much shorter than Q2 has spurred speculation that Q1 is an early draft, or perhaps an adaptation, a bootleg copy, or a stage adaptation. On the title page of Q2, its text is described as "newly imprinted and enlarged to almost as much again as it was." That is probably a comparison to Q1.[78]

Language

Much of Hamlet's language is courtly: elaborate, witty discourse, as recommended by Baldassare Castiglione's 1528 etiquette guide, The Courtier. This work specifically advises royal retainers to amuse their masters with inventive language. Osric and Polonius, especially, seem to respect this injunction. Claudius's speech is rich with rhetorical figures—as is Hamlet's and, at times, Ophelia's—while the language of Horatio, the guards, and the gravediggers is simpler. Claudius's high status is reinforced by using the royal first person plural ("we" or "us"), and anaphora mixed with metaphor to resonate with Greek political speeches.[84]

Of all the characters, Hamlet has the greatest rhetorical skill. He uses highly developed metaphors, stichomythia, and in nine memorable words deploys both anaphora and asyndeton: "to die: to sleep— / To sleep, perchance to dream".[85] In contrast, when occasion demands, he is precise and straightforward, as when he explains his inward emotion to his mother: "But I have that within which passes show, / These but the trappings and the suits of woe".[86] At times, he relies heavily on puns to express his true thoughts while simultaneously concealing them.[87] Pauline Kiernan argues that Shakespeare changed English drama forever in Hamlet because he "showed how a character's language can often be saying several things at once, and contradictory meanings at that, to reflect fragmented thoughts and disturbed feelings". She gives the example of Hamlet's advice to Ophelia, "get thee to a nunnery",[88] which, she claims, is simultaneously a reference to a place of chastity and a slang term for a brothel, reflecting Hamlet's confused feelings about female sexuality.[89] However Harold Jenkins does not agree, having studied the few examples that are used to support that idea, and finds that there is no support for the assumption that "nunnery" was used that way in slang, or that Hamlet intended such a meaning. The context of the scene suggests that a nunnery would not be a brothel, but instead a place of renunciation and a "sanctuary from marriage and from the world’s contamination".[90] Thompson and Taylor consider the brothel idea incorrect considering that "Hamlet is trying to deter Ophelia from breeding".[91]

Hamlet’s first words in the play are a pun; when Claudius addresses him as "my cousin Hamlet, and my son", Hamlet says as an aside: "A little more than kin, and less than kind."[92]

An unusual rhetorical device, hendiadys, appears in several places in the play. Examples are found in Ophelia's speech at the end of the nunnery scene: "Th'expectancy and rose of the fair state"[93] and "And I, of ladies most deject and wretched".[94] Many scholars have found it odd that Shakespeare would, seemingly arbitrarily, use this rhetorical form throughout the play. One explanation may be that Hamlet was written later in Shakespeare's life, when he was adept at matching rhetorical devices to characters and the plot. Linguist George T. Wright suggests that hendiadys had been used deliberately to heighten the play's sense of duality and dislocation.[95]

Hamlet's soliloquies have also captured the attention of scholars. Hamlet interrupts himself, vocalising either disgust or agreement with himself and embellishing his own words. He has difficulty expressing himself directly and instead blunts the thrust of his thought with wordplay. It is not until late in the play, after his experience with the pirates, that Hamlet is able to articulate his feelings freely.[96]

Context and interpretation

Religious

Written at a time of religious upheaval and in the wake of the English Reformation, the play is alternately Catholic (or piously medieval) and Protestant (or consciously modern). The ghost describes himself as being in purgatory and as dying without last rites. This and Ophelia's burial ceremony, which is characteristically Catholic, make up most of the play's Catholic connections. Some scholars have observed that revenge tragedies come from Catholic countries such as Italy and Spain, where the revenge tragedies present contradictions of motives, since according to Catholic doctrine the duty to God and family precedes civil justice. Hamlet's conundrum then is whether to avenge his father and kill Claudius or to leave the vengeance to God, as his religion requires.[97][lower-alpha 2]

Much of the play's Protestant tones derive from its setting in Denmark—both then and now a predominantly Protestant country,[lower-alpha 3] though it is unclear whether the fictional Denmark of the play is intended to portray this implicit fact. Dialogue refers explicitly to the German city of Wittenberg where Hamlet, Horatio, and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern attend university, implying where the Protestant reformer Martin Luther nailed the Ninety-five Theses to the church door in 1517.[98]

Philosophical

Hamlet is often perceived as a philosophical character, expounding ideas that are now described as relativist, existentialist, and sceptical. For example, he expresses a subjectivistic idea when he says to Rosencrantz: "there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so". [99] The idea that nothing is real except in the mind of the individual finds its roots in the Greek Sophists, who argued that since nothing can be perceived except through the senses—and since all individuals sense, and therefore perceive things differently—there is no absolute truth, but rather only relative truth.[100] The clearest alleged instance of existentialism is in the "to be, or not to be"[101] speech, where Hamlet is thought by some to use "being" to allude to life and action, and "not being" to death and inaction.

Hamlet reflects the contemporary scepticism promoted by the French Renaissance humanist Michel de Montaigne.[102] Prior to Montaigne's time, humanists such as Pico della Mirandola had argued that man was God's greatest creation, made in God's image and able to choose his own nature, but this view was subsequently challenged in Montaigne's Essais of 1580. Hamlet's "What a piece of work is a man" seems to echo many of Montaigne's ideas, and many scholars have discussed whether Shakespeare drew directly from Montaigne or whether both men were simply reacting similarly to the spirit of the times.[103][104][102]

Psychoanalytic

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud’s thoughts regarding Hamlet were first published in his book The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), as a footnote to a discussion of Sophocles’ tragedy, Oedipus Rex, all of which is part of his consideration of the causes of neurosis. Freud does not offer over-all interpretations of the plays, but uses the two tragedies to illustrate and corroborate his psychological theories, which are based on his treatments of his patients and on his studies. Productions of Hamlet have used Freud's ideas to support their own interpretations.[105][106] In The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud says that according to his experience "parents play a leading part in the infantile psychology of all persons who subsequently become psychoneurotics," and that "falling in love with one parent and hating the other" is a common impulse in early childhood, and is important source material of "subsequent neurosis". He says that "in their amorous or hostile attitude toward their parents" neurotics reveal something that occurs with less intensity "in the minds of the majority of children". Freud considered that Sophocles’ tragedy, Oedipus Rex, with its story that involves crimes of parricide and incest, "has furnished us with legendary matter which corroborates" these ideas, and that the "profound and universal validity of the old legends" is understandable only by recognizing the validity of these theories of "infantile psychology".[107]

Freud explores the reason "Oedipus Rex is capable of moving a modern reader or playgoer no less powerfully than it moved the contemporary Greeks". He suggests that "It may be that we were all destined to direct our first sexual impulses toward our mothers, and our first impulses of hatred and violence toward our fathers." Freud suggests that we "recoil from the person for whom this primitive wish of our childhood has been fulfilled with all the force of the repression which these wishes have undergone in our minds since childhood."[107]

These ideas, which became a cornerstone of Freud's psychological theories, he named the "Oedipus complex", and, at one point, he considered calling it the "Hamlet complex".[108] Freud considered that Hamlet "is rooted in the same soil as Oedipus Rex." But the difference in the "psychic life" of the two civilizations that produced each play, and the progress made over time of "repression in the emotional life of humanity" can be seen in the way the same material is handled by the two playwrights: In Oedipus Rex incest and murder are brought into the light as might occur in a dream, but in Hamlet these impulses "remain repressed" and we learn of their existence through Hamlet's inhibitions to act out the revenge, while he is shown to be capable of acting decisively and boldly in other contexts. Freud asserts, "The play is based on Hamlet’s hesitation in accomplishing the task of revenge assigned to him; the text does not give the cause or the motive of this." The conflict is "deeply hidden".[109]

Hamlet is able to perform any kind of action except taking revenge on the man who murdered his father and has taken his father's place with his mother—Claudius has led Hamlet to realize the repressed desires of his own childhood. The loathing which was supposed to drive him to revenge is replaced by "self-reproach, by conscientious scruples" which tell him "he himself is no better than the murderer whom he is required to punish".[110] Freud suggests that Hamlet's sexual aversion expressed in his "nunnery" conversation with Ophelia supports the idea that Hamlet is "an hysterical subject".[110][111]

Freud suggests that the character Hamlet goes through an experience that has three characteristics, which he numbered: 1) "the hero is not psychopathic, but becomes so" during the course of the play. 2) "the repressed desire is one of those that are similarly repressed in all of us." It is a repression that "belongs to an early stage of our individual development". The audience identifies with the character of Hamlet, because "we are victims of the same conflict." 3) It is the nature of theatre that "the struggle of the repressed impulse to become conscious" occurs in both the hero onstage and the spectator, when they are in the grip of their emotions, "in the manner seen in psychoanalytic treatment".[112]

Freud points out that Hamlet is an exception in that psychopathic characters are usually ineffective in stage plays; they "become as useless for the stage as they are for life itself", because they do not inspire insight or empathy, unless the audience is familiar with the character's inner conflict. Freud says, "It is thus the task of the dramatist to transport us into the same illness."[113]

John Barrymore's long-running 1922 performance in New York, directed by Thomas Hopkins, "broke new ground in its Freudian approach to character", in keeping with the post-World War I rebellion against everything Victorian.[114] He had a "blunter intention" than presenting the genteel, sweet prince of 19th-century tradition, imbuing his character with virility and lust.[115]

Beginning in 1910, with the publication of "The Œdipus-Complex as an Explanation of Hamlet's Mystery: A Study in Motive"[116] Ernest Jones—a psychoanalyst and Freud's biographer—developed Freud's ideas into a series of essays that culminated in his book Hamlet and Oedipus (1949). Influenced by Jones's psychoanalytic approach, several productions have portrayed the "closet scene", where Hamlet confronts his mother in her private quarters, in a sexual light.[117] In this reading, Hamlet is disgusted by his mother's "incestuous" relationship with Claudius while simultaneously fearful of killing him, as this would clear Hamlet's path to his mother's bed. Ophelia's madness after her father's death may also be read through the Freudian lens: as a reaction to the death of her hoped-for lover, her father. Ophelia is overwhelmed by having her unfulfilled love for him so abruptly terminated and drifts into the oblivion of insanity.[118][119] In 1937, Tyrone Guthrie directed Laurence Olivier in a Jones-inspired Hamlet at The Old Vic.[120] Olivier later used some of these same ideas in his 1948 film version of the play.

In the Bloom's Shakespeare Through the Ages volume on Hamlet, editors Bloom and Foster express a conviction that the intentions of Shakespeare in portraying the character of Hamlet in the play exceeded the capacity of the Freudian Oedipus complex to completely encompass the extent of characteristics depicted in Hamlet throughout the tragedy: "For once, Freud regressed in attempting to fasten the Oedipus Complex upon Hamlet: it will not stick, and merely showed that Freud did better than T.S. Eliot, who preferred Coriolanus to Hamlet, or so he said. Who can believe Eliot, when he exposes his own Hamlet Complex by declaring the play to be an aesthetic failure?"[121] The book also notes James Joyce's interpretation, stating that he "did far better in the Library Scene of Ulysses, where Stephen marvellously credits Shakespeare, in this play, with universal fatherhood while accurately implying that Hamlet is fatherless, thus opening a pragmatic gap between Shakespeare and Hamlet."[121]

Joshua Rothman has written in The New Yorker that "we tell the story wrong when we say that Freud used the idea of the Oedipus complex to understand Hamlet". Rothman suggests that "it was the other way around: Hamlet helped Freud understand, and perhaps even invent, psychoanalysis". He concludes, "The Oedipus complex is a misnomer. It should be called the 'Hamlet complex'."[122]

Jacques Lacan

In the 1950s, the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan analyzed Hamlet to illustrate some of his concepts. His structuralist theories about Hamlet were first presented in a series of seminars given in Paris and later published in "Desire and the Interpretation of Desire in Hamlet". Lacan postulated that the human psyche is determined by structures of language and that the linguistic structures of Hamlet shed light on human desire.[123] His point of departure is Freud's Oedipal theories, and the central theme of mourning that runs through Hamlet.[124] In Lacan's analysis, Hamlet unconsciously assumes the role of phallus—the cause of his inaction—and is increasingly distanced from reality "by mourning, fantasy, narcissism and psychosis", which create holes (or lack) in the real, imaginary, and symbolic aspects of his psyche.[123] Lacan's theories influenced some subsequent literary criticism of Hamlet because of his alternative vision of the play and his use of semantics to explore the play's psychological landscape.[123]

Feminist

In the 20th century, feminist critics opened up new approaches to Gertrude and Ophelia. New historicist and cultural materialist critics examined the play in its historical context, attempting to piece together its original cultural environment.[126] They focused on the gender system of early modern England, pointing to the common trinity of maid, wife, or widow, with whores outside of that stereotype. In this analysis, the essence of Hamlet is the central character's changed perception of his mother as a whore because of her failure to remain faithful to Old Hamlet. In consequence, Hamlet loses his faith in all women, treating Ophelia as if she too were a whore and dishonest with Hamlet. Ophelia, by some critics, can be seen as honest and fair; however, it is virtually impossible to link these two traits, since 'fairness' is an outward trait, while 'honesty' is an inward trait.[127]

Carolyn Heilbrun's 1957 essay "The Character of Hamlet's Mother" defends Gertrude, arguing that the text never hints that Gertrude knew of Claudius poisoning King Hamlet. This analysis has been praised by many feminist critics, combating what is, by Heilbrun's argument, centuries' worth of misinterpretation. By this account, Gertrude's worst crime is of pragmatically marrying her brother-in-law in order to avoid a power vacuum. This is borne out by the fact that King Hamlet's ghost tells Hamlet to leave Gertrude out of Hamlet's revenge, to leave her to heaven, an arbitrary mercy to grant to a conspirator to murder.[128][129][130]

Ophelia has also been defended by feminist critics, most notably Elaine Showalter.[131] Ophelia is surrounded by powerful men: her father, brother, and Hamlet. All three disappear: Laertes leaves, Hamlet abandons her, and Polonius dies. Conventional theories had argued that without these three powerful men making decisions for her, Ophelia is driven into madness.[132] Feminist theorists argue that she goes mad with guilt because, when Hamlet kills her father, he has fulfilled her sexual desire to have Hamlet kill her father so they can be together. Showalter points out that Ophelia has become the symbol of the distraught and hysterical woman in modern culture.[133]

Influence

Hamlet is one of the most quoted works in the English language, and is often included on lists of the world's greatest literature.[lower-alpha 4] As such, it reverberates through the writing of later centuries. Academic Laurie Osborne identifies the direct influence of Hamlet in numerous modern narratives, and divides them into four main categories: fictional accounts of the play's composition, simplifications of the story for young readers, stories expanding the role of one or more characters, and narratives featuring performances of the play.[134]

English poet John Milton was an early admirer of Shakespeare and took evident inspiration from his work. As John Kerrigan discusses, Milton originally considered writing his epic poem Paradise Lost (1667) as a tragedy.[135] While Milton did not ultimately go that route, the poem still shows distinct echoes of Shakespearean revenge tragedy, and of Hamlet in particular. As scholar Christopher N. Warren argues, Paradise Lost's Satan "undergoes a transformation in the poem from a Hamlet-like avenger into a Claudius-like usurper," a plot device that supports Milton's larger Republican internationalist project.[136] The poem also reworks theatrical language from Hamlet, especially around the idea of "putting on" certain dispositions, as when Hamlet puts on "an antic disposition," similarly to the Son in Paradise Lost who "can put on / [God's] terrors."[137]

Henry Fielding's Tom Jones, published about 1749, describes a visit to Hamlet by Tom Jones and Mr Partridge, with similarities to the "play within a play".[138] In contrast, Goethe's Bildungsroman Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship, written between 1776 and 1796, not only has a production of Hamlet at its core but also creates parallels between the ghost and Wilhelm Meister's dead father.[138] In the early 1850s, in Pierre, Herman Melville focuses on a Hamlet-like character's long development as a writer.[138] Ten years later, Dickens's Great Expectations contains many Hamlet-like plot elements: it is driven by revenge-motivated actions, contains ghost-like characters (Abel Magwitch and Miss Havisham), and focuses on the hero's guilt.[138] Academic Alexander Welsh notes that Great Expectations is an "autobiographical novel" and "anticipates psychoanalytic readings of Hamlet itself".[139] About the same time, George Eliot's The Mill on the Floss was published, introducing Maggie Tulliver "who is explicitly compared with Hamlet"[140] though "with a reputation for sanity".[141]

L. Frank Baum's first published short story was "They Played a New Hamlet" (1895). When Baum had been touring New York State in the title role, the actor playing the ghost fell through the floorboards, and the rural audience thought it was part of the show and demanded that the actor repeat the fall, because they thought it was funny. Baum would later recount the actual story in an article, but the short story is told from the point of view of the actor playing the ghost.

In the 1920s, James Joyce managed "a more upbeat version" of Hamlet—stripped of obsession and revenge—in Ulysses, though its main parallels are with Homer's Odyssey.[138] In the 1990s, two novelists were explicitly influenced by Hamlet. In Angela Carter's Wise Children, To be or not to be is reworked as a song and dance routine, and Iris Murdoch's The Black Prince has Oedipal themes and murder intertwined with a love affair between a Hamlet-obsessed writer, Bradley Pearson, and the daughter of his rival.[140] In the late 20th century, David Foster Wallace's novel Infinite Jest draws heavily from Hamlet and takes its title from the play's text; Wallace incorporates references to the gravedigger scene, the marriage of the main character's mother to his uncle, and the re-appearance of the main character's father as a ghost.

There is the story of the woman who read Hamlet for the first time and said, "I don't see why people admire that play so. It is nothing but a bunch of quotations strung together."

— Isaac Asimov, Asimov's Guide to Shakespeare, p. vii, Avenal Books, 1970

Performance history

The day we see Hamlet die in the theatre, something of him dies for us. He is dethroned by the spectre of an actor, and we shall never be able to keep the usurper out of our dreams.

Maurice Maeterlinck in La Jeune Belgique (1890).[142]

Shakespeare's day to the Interregnum

Shakespeare almost certainly wrote the role of Hamlet for Richard Burbage. He was the chief tragedian of the Lord Chamberlain's Men, with a capacious memory for lines and a wide emotional range.[143][144][lower-alpha 5] Judging by the number of reprints, Hamlet appears to have been Shakespeare's fourth most popular play during his lifetime—only Henry IV Part 1, Richard III and Pericles eclipsed it.[148] Shakespeare provides no clear indication of when his play is set; however, as Elizabethan actors performed at the Globe in contemporary dress on minimal sets, this would not have affected the staging.[149]

Firm evidence for specific early performances of the play is scant. It is sometimes argued that the crew of the ship Red Dragon, anchored off Sierra Leone, performed Hamlet in September 1607;[150][151][152] however, this claim is based on a 19th century insert of a 'lost' passage into a period document, and is today widely regarded as a hoax, likely to have been perpetrated by John Payne Collier[153] (not to mention the intrinsic unlikelihood of sailors memorising and performing the play). More credible is that the play toured in Germany within five years of Shakespeare's death,[152] and that it was performed before James I in 1619 and Charles I in 1637.[154] Oxford editor George Hibbard argues that, since the contemporary literature contains many allusions and references to Hamlet (only Falstaff is mentioned more, from Shakespeare), the play was surely performed with a frequency that the historical record misses.[155]

All theatres were closed down by the Puritan government during the Interregnum.[156] Even during this time, however, playlets known as drolls were often performed illegally, including one called The Grave-Makers based on act 5, scene 1 of Hamlet.[157]

Restoration and 18th century

The play was revived early in the Restoration. When the existing stock of pre-civil war plays was divided between the two newly created patent theatre companies, Hamlet was the only Shakespearean favourite that Sir William Davenant's Duke's Company secured.[158] It became the first of Shakespeare's plays to be presented with movable flats painted with generic scenery behind the proscenium arch of Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre.[lower-alpha 6] This new stage convention highlighted the frequency with which Shakespeare shifts dramatic location, encouraging the recurrent criticism of his failure to maintain unity of place.[160] In the title role, Davenant cast Thomas Betterton, who continued to play the Dane until he was 74.[161] David Garrick at Drury Lane produced a version that adapted Shakespeare heavily; he declared: "I had sworn I would not leave the stage till I had rescued that noble play from all the rubbish of the fifth act. I have brought it forth without the grave-digger's trick, Osrick, & the fencing match".[lower-alpha 7] The first actor known to have played Hamlet in North America is Lewis Hallam Jr., in the American Company's production in Philadelphia in 1759.[163]

John Philip Kemble made his Drury Lane debut as Hamlet in 1783.[164] His performance was said to be 20 minutes longer than anyone else's, and his lengthy pauses provoked the suggestion by Richard Brinsley Sheridan that "music should be played between the words".[165] Sarah Siddons was the first actress known to play Hamlet; many women have since played him as a breeches role, to great acclaim.[166] In 1748, Alexander Sumarokov wrote a Russian adaptation that focused on Prince Hamlet as the embodiment of an opposition to Claudius's tyranny—a treatment that would recur in Eastern European versions into the 20th century.[167] In the years following America's independence, Thomas Abthorpe Cooper, the young nation's leading tragedian, performed Hamlet among other plays at the Chestnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia, and at the Park Theatre in New York. Although chided for "acknowledging acquaintances in the audience" and "inadequate memorisation of his lines", he became a national celebrity.[168]

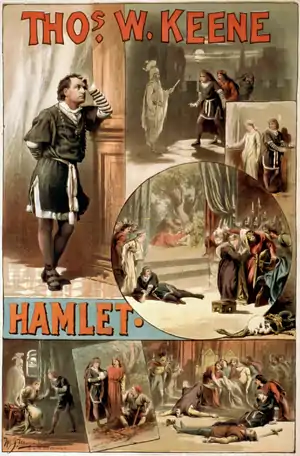

19th century

From around 1810 to 1840, the best-known Shakespearean performances in the United States were tours by leading London actors—including George Frederick Cooke, Junius Brutus Booth, Edmund Kean, William Charles Macready, and Charles Kemble. Of these, Booth remained to make his career in the States, fathering the nation's most notorious actor, John Wilkes Booth (who later assassinated Abraham Lincoln), and its most famous Hamlet, Edwin Booth.[169] Edwin Booth's Hamlet at the Fifth Avenue Theatre in 1875 was described as "... the dark, sad, dreamy, mysterious hero of a poem. [... acted] in an ideal manner, as far removed as possible from the plane of actual life".[170][171] Booth played Hamlet for 100 nights in the 1864/5 season at the Winter Garden Theatre, inaugurating the era of long-run Shakespeare in America.[171]

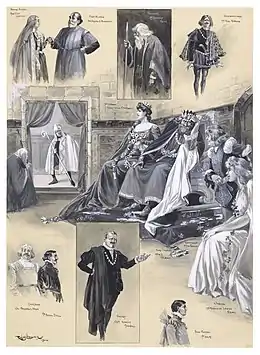

In the United Kingdom, the actor-managers of the Victorian era (including Kean, Samuel Phelps, Macready, and Henry Irving) staged Shakespeare in a grand manner, with elaborate scenery and costumes.[172] The tendency of actor-managers to emphasise the importance of their own central character did not always meet with the critics' approval. George Bernard Shaw's praise for Johnston Forbes-Robertson's performance contains a sideswipe at Irving: "The story of the play was perfectly intelligible, and quite took the attention of the audience off the principal actor at moments. What is the Lyceum coming to?"[lower-alpha 8]

In London, Edmund Kean was the first Hamlet to abandon the regal finery usually associated with the role in favour of a plain costume, and he is said to have surprised his audience by playing Hamlet as serious and introspective.[174] In stark contrast to earlier opulence, William Poel's 1881 production of the Q1 text was an early attempt at reconstructing the Elizabethan theatre's austerity; his only backdrop was a set of red curtains.[46][175] Sarah Bernhardt played the prince in her popular 1899 London production. In contrast to the "effeminate" view of the central character that usually accompanied a female casting, she described her character as "manly and resolute, but nonetheless thoughtful ... [he] thinks before he acts, a trait indicative of great strength and great spiritual power".[lower-alpha 9]

In France, Charles Kemble initiated an enthusiasm for Shakespeare; and leading members of the Romantic movement such as Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas saw his 1827 Paris performance of Hamlet, particularly admiring the madness of Harriet Smithson's Ophelia.[177] In Germany, Hamlet had become so assimilated by the mid-19th century that Ferdinand Freiligrath declared that "Germany is Hamlet".[178] From the 1850s, the Parsi theatre tradition in India transformed Hamlet into folk performances, with dozens of songs added.[179]

20th century

Apart from some western troupes' 19th-century visits, the first professional performance of Hamlet in Japan was Otojirō Kawakami's 1903 Shinpa ("new school theatre") adaptation.[180] Tsubouchi Shōyō translated Hamlet and produced a performance in 1911 that blended Shingeki ("new drama") and Kabuki styles.[180] This hybrid-genre reached its peak in Tsuneari Fukuda's 1955 Hamlet.[180] In 1998, Yukio Ninagawa produced an acclaimed version of Hamlet in the style of Nō theatre, which he took to London.[181]

Konstantin Stanislavski and Edward Gordon Craig—two of the 20th century's most influential theatre practitioners—collaborated on the Moscow Art Theatre's seminal production of 1911–12.[lower-alpha 10] While Craig favoured stylised abstraction, Stanislavski, armed with his 'system,' explored psychological motivation.[183] Craig conceived of the play as a symbolist monodrama, offering a dream-like vision as seen through Hamlet's eyes alone.[lower-alpha 11] This was most evident in the staging of the first court scene.[187][lower-alpha 12] The most famous aspect of the production is Craig's use of large, abstract screens that altered the size and shape of the acting area for each scene, representing the character's state of mind spatially or visualising a dramaturgical progression.[189] The production attracted enthusiastic and unprecedented worldwide attention for the theatre and placed it "on the cultural map for Western Europe".[190][191]

The first modern dress stagings of Hamlet happened in 1925 in London and then New York. Barry Jackson's Birmingham Repertory Theatre opened their production, directed by H.K. Ayliff at the Kingsway Theatre on August 25, 1925.[192] Ivor Brown reported, "Many of the first night audience came to scoff and remained to hold its breath, to marvel and enjoy. . . .Shakespeare's victory over time and tailoring was swift and sweeping."[193] Horace Brisbin Liveright's modern dress production opened at the Booth Theater in New York on November 9, 1925, the same night that the London production moved to Birmingham. It was known "more dryly, and perhaps with a touch of something more sinister, as 'the plain-clothes Hamlet'" and did not reach the same level of success.[192]

Hamlet is often played with contemporary political overtones. Leopold Jessner's 1926 production at the Berlin Staatstheater portrayed Claudius's court as a parody of the corrupt and fawning court of Kaiser Wilhelm.[194] In Poland, the number of productions of Hamlet has tended to increase at times of political unrest, since its political themes (suspected crimes, coups, surveillance) can be used to comment on a contemporary situation.[195] Similarly, Czech directors have used the play at times of occupation: a 1941 Vinohrady Theatre production "emphasised, with due caution, the helpless situation of an intellectual attempting to endure in a ruthless environment".[196][197] In China, performances of Hamlet often have political significance: Gu Wuwei's 1916 The Usurper of State Power, an amalgam of Hamlet and Macbeth, was an attack on Yuan Shikai's attempt to overthrow the republic.[198] In 1942, Jiao Juyin directed the play in a Confucian temple in Sichuan Province, to which the government had retreated from the advancing Japanese.[198] In the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the protests at Tiananmen Square, Lin Zhaohua staged a 1990 Hamlet in which the prince was an ordinary individual tortured by a loss of meaning. In this production, the actors playing Hamlet, Claudius and Polonius exchanged roles at crucial moments in the performance, including the moment of Claudius's death, at which point the actor mainly associated with Hamlet fell to the ground.[199]

Notable stagings in London and New York include Barrymore's 1925 production at the Haymarket; it influenced subsequent performances by John Gielgud and Laurence Olivier.[200][201] Gielgud played the central role many times: his 1936 New York production ran for 132 performances, leading to the accolade that he was "the finest interpreter of the role since Barrymore".[202] Although "posterity has treated Maurice Evans less kindly", throughout the 1930s and 1940s he was regarded by many as the leading interpreter of Shakespeare in the United States and in the 1938/39 season he presented Broadway's first uncut Hamlet, running four and a half hours.[203] Evans later performed a highly truncated version of the play that he played for South Pacific war zones during World War II which made the prince a more decisive character. The staging, known as the "G.I. Hamlet", was produced on Broadway for 131 performances in 1945/46.[204] Olivier's 1937 performance at The Old Vic was popular with audiences but not with critics, with James Agate writing in a famous review in The Sunday Times, "Mr. Olivier does not speak poetry badly. He does not speak it at all."[205] In 1937 Tyrone Guthrie directed the play at Elsinore, Denmark, with Laurence Olivier as Hamlet and Vivien Leigh as Ophelia.

In 1963, Olivier directed Peter O'Toole as Hamlet in the inaugural performance of the newly formed National Theatre; critics found resonance between O'Toole's Hamlet and John Osborne's hero, Jimmy Porter, from Look Back in Anger.[206][207]

Richard Burton received his third Tony Award nomination when he played his second Hamlet, his first under John Gielgud's direction, in 1964 in a production that holds the record for the longest run of the play in Broadway history (137 performances). The performance was set on a bare stage, conceived to appear like a dress rehearsal, with Burton in a black v-neck sweater, and Gielgud himself tape-recorded the voice for the ghost (which appeared as a looming shadow). It was immortalised both on record and on a film that played in US theatres for a week in 1964 as well as being the subject of books written by cast members William Redfield and Richard L. Sterne.

Other New York portrayals of Hamlet of note include that of Ralph Fiennes's in 1995 (for which he won the Tony Award for Best Actor)—which ran, from first preview to closing night, a total of one hundred performances. About the Fiennes Hamlet Vincent Canby wrote in The New York Times that it was "... not one for literary sleuths and Shakespeare scholars. It respects the play, but it doesn't provide any new material for arcane debates on what it all means. Instead it's an intelligent, beautifully read ..."[208] Stacy Keach played the role with an all-star cast at Joseph Papp's Delacorte Theater in the early 1970s, with Colleen Dewhurst's Gertrude, James Earl Jones's King, Barnard Hughes's Polonius, Sam Waterston's Laertes and Raul Julia's Osric. Sam Waterston later played the role himself at the Delacorte for the New York Shakespeare Festival, and the show transferred to the Vivian Beaumont Theater in 1975 (Stephen Lang played Bernardo and other roles). Stephen Lang's Hamlet for the Roundabout Theatre Company in 1992 received mixed reviews[209][210] and ran for sixty-one performances. David Warner played the role with the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in 1965. William Hurt (at Circle Repertory Company off-Broadway, memorably performing "To be, or not to be" while lying on the floor), Jon Voight at Rutgers, and Christopher Walken (fiercely) at Stratford, Connecticut, have all played the role, as has Diane Venora at The Public Theatre. The Internet Broadway Database lists sixty-six productions of Hamlet.[211]

Ian Charleson performed Hamlet from 9 October to 13 November 1989, in Richard Eyre's production at the Olivier Theatre, replacing Daniel Day-Lewis, who had abandoned the production. Seriously ill from AIDS at the time, Charleson died eight weeks after his last performance. Fellow actor and friend, Sir Ian McKellen, said that Charleson played Hamlet so well it was as if he had rehearsed the role all his life; McKellen called it "the perfect Hamlet".[212][213] The performance garnered other major accolades as well, some critics echoing McKellen in calling it the definitive Hamlet performance.[214]

Keanu Reeves performed Hamlet from 12 January to 4 February 1995 at the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre (Winnipeg, Manitoba). The production garnered positive reviews from worldwide media outlets. Directed by Lewis Baumander the lavish production featured a cast of some of Canada's most distinguished classical actors of that period.[215]

21st century

Hamlet continues to be staged regularly. Actors performing the lead role have included: Simon Russell Beale, Ben Whishaw, David Tennant, Tom Hiddleston, Angela Winkler, Samuel West, Christopher Eccleston, Maxine Peake, Rory Kinnear, Oscar Isaac, Michael Sheen, Christian Camargo, Paapa Essiedu and Michael Urie.[216][217][218][219]

In May 2009, Hamlet opened with Jude Law in the title role at the Donmar Warehouse West End season at Wyndham's Theatre. The production officially opened on 3 June and ran through 22 August 2009.[220][221] A further production with Jude Law ran at Elsinore Castle in Denmark from 25–30 August 2009,[222] and then moved to Broadway, and ran for 12 weeks at the Broadhurst Theatre in New York.[223][224]

In October 2011, a production starring Michael Sheen opened at the Young Vic, in which the play was set inside a psychiatric hospital.[225]

In 2013, American actor Paul Giamatti played the title role of Hamlet in modern dress, at the Yale Repertory Theatre, at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.[226][227]

The Globe Theatre of London initiated a project in 2014 to perform Hamlet in every country in the world in the space of two years. Titled Globe to Globe Hamlet, it began its tour on 23 April 2014, the 450th anniversary of Shakespeare's birth, and performed in 197 countries.[228]

Benedict Cumberbatch played the role for a 12-week run in a production at the Barbican Theatre, opening on 25 August 2015. The play was produced by Sonia Friedman, and directed by Lyndsey Turner, with set design by Es Devlin. It was called the "most in-demand theatre production of all time" and sold out in seven hours after tickets went on sale 11 August 2014, more than a year before the play opened.[229][230]

A 2017 Almeida Theatre production, directed by Robert Icke and starring Andrew Scott, was transferred that same year to the West End's Harold Pinter Theatre.[231]

Tom Hiddleston played the role for a three-week run at Vanbrugh Theatre that opened on 1 September 2017 and was directed by Kenneth Branagh.[232][233]

In 2018, The Globe Theatre's newly instated artistic director Michelle Terry played the role in a production notable for its gender-blind casting.[234]

A production by Bristol Old Vic starring Billy Howle in title role, Niamh Cusack as Gertrude, Mirren Mack as Ophelia opened on 13 October 2022.[235]

Film and TV performances

An early film version of Hamlet is Sarah Bernhardt's five-minute film of the fencing scene,[236] which was produced in 1900. The film was an early attempt at combining sound and film; music and words were recorded on phonograph records, to be played along with the film.[237] Silent versions were released in 1907, 1908, 1910, 1913, 1917, and 1920.[238] In the 1921 film Hamlet, Danish actress Asta Nielsen played the role of Hamlet as a woman who spends her life disguised as a man.[237]

Laurence Olivier's 1948 moody black-and-white Hamlet won Best Picture and Best Actor Academy Awards, and is, as of 2020, the only Shakespeare film to have done so. His interpretation stressed the Oedipal overtones of the play, and cast 28-year-old Eileen Herlie as Hamlet's mother, opposite himself, at 41, as Hamlet.[239]

In 1953, actor Jack Manning performed the play in 15-minute segments over two weeks in the short-lived late night DuMont series Monodrama Theater. New York Times TV critic Jack Gould praised Manning's performance as Hamlet.[240]

The 1964 Soviet film Hamlet (Russian: Гамлет) is based on a translation by Boris Pasternak and directed by Grigori Kozintsev, with a score by Dmitri Shostakovich.[241] Innokenty Smoktunovsky was cast in the role of Hamlet.

John Gielgud directed Richard Burton in a Broadway production at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre in 1964–65, the longest-running Hamlet in the U.S. to date. A live film of the production was produced using "Electronovision", a method of recording a live performance with multiple video cameras and converting the image to film.[242] Eileen Herlie repeated her role from Olivier's film version as the Queen, and the voice of Gielgud was heard as the ghost. The Gielgud/Burton production was also recorded complete and released on LP by Columbia Masterworks.

The first Hamlet in color was a 1969 film directed by Tony Richardson with Nicol Williamson as Hamlet and Marianne Faithfull as Ophelia.

In 1990 Franco Zeffirelli, whose Shakespeare films have been described as "sensual rather than cerebral",[243] cast Mel Gibson—then famous for the Mad Max and Lethal Weapon movies—in the title role of his 1990 version; Glenn Close—then famous as the psychotic "other woman" in Fatal Attraction—played Gertrude, and Paul Scofield played Hamlet's father.[244]

Kenneth Branagh adapted, directed, and starred in a 1996 film version of Hamlet that contained material from the First Folio and the Second Quarto. Branagh's Hamlet runs for just over four hours.[245] Branagh set the film with late 19th-century costuming and furnishings, a production in many ways reminiscent of a Russian novel of the time;[246] and Blenheim Palace, built in the early 18th century, became Elsinore Castle in the external scenes. The film is structured as an epic and makes frequent use of flashbacks to highlight elements not made explicit in the play: Hamlet's sexual relationship with Kate Winslet's Ophelia, for example, or his childhood affection for Yorick (played by Ken Dodd).[247]

In 2000, Michael Almereyda's Hamlet set the story in contemporary Manhattan, with Ethan Hawke playing Hamlet as a film student. Claudius (played by Kyle MacLachlan) became the CEO of "Denmark Corporation", having taken over the company by killing his brother.[248]

The 2014 Bollywood film Haider is an adaptation set in modern Kashmir.[249]

The Northman, released on 22 April 2022 and directed by the American director Robert Eggers who also co-wrote the script with Icelandic author Sjón, is based in the original Scandinavian legend that inspired Shakespeare to write Hamlet.

Derivative works

This section is limited to derivative works written for the stage.

Tom Stoppard's 1966 play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead retells many of the events of the story from the point of view of the characters Rosencrantz and Guildenstern and gives them a backstory of their own. Several times since 1995, the American Shakespeare Center has mounted repertories that included both Hamlet and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, with the same actors performing the same roles in each; in their 2001 and 2009 seasons the two plays were "directed, designed, and rehearsed together to make the most out of the shared scenes and situations".[250]

W. S. Gilbert wrote a short comic play titled Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, in which Hamlet's play is presented as a tragedy written by Claudius in his youth of which he is greatly embarrassed. Through the chaos triggered by Hamlet's staging of it, Guildenstern helps Rosencrantz vie with Hamlet to make Ophelia his bride.[251]

Lee Blessing's Fortinbras is a comical sequel to Hamlet in which all the deceased characters come back as ghosts. The New York Times reviewed the play, saying it is "scarcely more than an extended comedy sketch, lacking the portent and linguistic complexity of Tom Stoppard's Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. Fortinbras operates on a far less ambitious plane, but it is a ripping yarn and offers Keith Reddin a role in which he can commit comic mayhem".[252]

Caridad Svich's 12 Ophelias (a play with broken songs) includes elements of the story of Hamlet but focuses on Ophelia. In Svich's play, Ophelia is resurrected and rises from a pool of water, after her death in Hamlet. The play is a series of scenes and songs, and was first staged at a public swimming pool in Brooklyn.[253]

David Davalos's Wittenberg is a "tragical-comical-historical" prequel to Hamlet that depicts the Danish prince as a student at Wittenberg University (now known as the University of Halle-Wittenberg), where he is torn between the conflicting teachings of his mentors John Faustus and Martin Luther. The New York Times reviewed the play, saying, "Mr. Davalos has molded a daft campus comedy out of this unlikely convergence",[254] and Nytheatre.com's review said the playwright "has imagined a fascinating alternate reality, and quite possibly, given the fictional Hamlet a back story that will inform the role for the future."[255]

Mad Boy Chronicle by Canadian playwright Michael O'Brien is a dark comedy loosely based on Hamlet, set in Viking Denmark in 999 AD.[256]

Notes and references

Notes

- The Arden Shakespeare third series published Q2, with appendices, in their first volume,[50] and the F1 and Q1 texts in their second volume.[51] The RSC Shakespeare is the F1 text with additional Q2 passages in an appendix.[52] The New Cambridge Shakespeare series has begun to publish separate volumes for the separate quarto versions that exist of Shakespeare's plays.[53]

- See Romans 12:19: Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord.

- See the articles on the Reformation in Denmark–Norway and Holstein and Church of Denmark for details.

- Hamlet has 208 quotations in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations; it takes up 10 of 85 pages dedicated to Shakespeare in the 1986 Bartlett's Familiar Quotations (14th ed. 1968). For examples of lists of the greatest books, see Harvard Classics, Great Books, Great Books of the Western World, Harold Bloom's The Western Canon, St. John's College reading list, and Columbia College Core Curriculum.

- Hattaway asserts that "Richard Burbage ... played Hieronimo and also Richard III but then was the first Hamlet, Lear, and Othello"[145] and Thomson argues that the identity of Hamlet as Burbage is built into the dramaturgy of several moments of the play: "we will profoundly misjudge the position if we do not recognise that, whilst this is Hamlet talking about the groundlings, it is also Burbage talking to the groundlings".[146] See also Thomson on the first player's beard.[147]

- Samuel Pepys records his delight at the novelty of Hamlet "done with scenes".[159]

- Letter to Sir William Young, 10 January 1773, quoted by Uglow.[162]

- George Bernard Shaw in The Saturday Review on 2 October 1897.[173]

- Sarah Bernhardt, in a letter to the London Daily Telegraph.[176]