Maria Clara gown

The María Clara gown, historically known as the traje de mestiza during the Spanish colonial era,[1][2] is a type of traditional dress worn by women in the Philippines. It is an aristocratic version of the baro't saya. It takes its name from María Clara, the mestiza protagonist of the novel Noli Me Tángere, penned in 1887 by Filipino nationalist José Rizal. It is traditionally made out of piña, the same material used for the barong tagalog.[3]

A unified gown version of the dress with butterfly sleeves popularized in the first half of the 20th century by Philippine National Artist Ramon Valera is known as the terno,[4] which also has a shorter casual and cocktail dress version known as the balintawak.[5] The masculine equivalent of baro't saya is the barong tagalog.[6]

These traditional women's dresses in the Philippines are collectively known as Filipiniana dress. Along with the barong tagalog, they are also collectively known as "Filipiniana attire".[7][8]

Traditional components

Like the baro't saya, the Maria Clara gown traditionally consists of four parts: a blouse (baro or camisa), a long skirt (saya), a kerchief worn over the shoulders (pañuelo, fichu, or alampay), and a short rectangular cloth worn over the skirt (the tapis or patadyong).[9]

The camisa is a collarless blouse whose hem is at the waist and is made from flimsy, translucent fabrics such as pineapple fiber and jusi. The sleeves of the camisa are similar to the so-called "angel wings", or shaped like bells. The correct term for the sleeves of the camisa during the mid to late 1800s is a "pagoda" – derived from early Western silhouettes of the Victorian period.[10]

The pañuelo is a piece of starched square cloth (either opaque or made from the same material as of the camisa) folded several times and placed over the shoulders. The purpose of the pañuelo has been related to modesty, used to cover the nape and the upper body due to the camisa's low neckline as well as its sheer translucency; and also doubles as an accent piece because of embellishments added to it, usually embroideries and the pin securing it in place.

The saya is a skirt shaped like a "cupola",[11] the length begins from the waist reaching the floor. These are usually comprised either of single or double sheets, called "panels" or dos paños (Spanish for "two cloths"); some examples are made out of seven gores or siete cuchillos (Spanish for "seven knives").

The tapis is a knee-length over-skirt that hugs the hips. Tapis designs may be plain, and is usually made of opaque fabrics such as muslin and the madras cloth, and also is used for the purposes of modesty as it keeps the lower body from showing due to the thinness of the saya.[3]

Some ladies belonging to the higher classes (often of the mestiza caste) consider the tapis a lowly piece of clothing. It resembled the dalantal (apron) worn by the lower classes. The upper-class women of the 1880s to the 1890s wore an elaborate[10] version of the tapis that was tied around the waist with two strings. This was also referred to as a "dalantal" (apron).[12]

Modernization

The word "terno" in Spanish refers to a matching set of clothes made of the same fabric. In the Philippines, "terno" refers to a woman's ensemble that consists of matching colors/patterns.[13] In the early 1900s, the traje de mestiza's components started to match in terms of color and patterns.[14] Some trajes in the 1910s were entirely made of the same material (such as "nipis" – a Filipino term meaning "fine" or "thin"[15]). By the 1920s the term referred to a dress consisting of a matching "camisa" with butterfly sleeves, a heavily starched "pañuelo" (fichu), a "saya" (skirt) which normally came with a "cola" (train), and a "sobrefalda" (overskirt).[14]

By the late 1940s, the terno's meaning and silhouette evolved into any Western dress with butterfly sleeves attached to it.[13]

Occasionally the "terno" would be referred to as a "mestiza dress" by women who lived in the first half of the 20th century.[14]

During July 8, 2008, State of the Nation Address of Philippine president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, she wore a "modernized María Clara gown". The adaptation donned by the president came was fuchsia-pink, designed by JC Buendia. Created in three weeks, the fabric used for the presidential gown was a blend of pineapple fibers and silk and was developed by the Philippine Research Institute, an agency of the Department of Science and Technology of the Philippines. The six-yard fabric costing ₱ 3,000 were produced in the province of Misamis Oriental, processed in Manila, and woven in the province of Aklan. The cloth was then colored with a dye from the sabang, a native plant.[16]

According to the Philippine Daily Inquirer, this is the first time in Philippine history that the media office of the Malacañang Palace revealed details about a Filipino president's evening outfit that would be worn for a State of the Nation Address. However, the president herself talked about the attire she wore in June 2008 during the 50th anniversary of the Department of Science and Technology. The aforementioned outfit was an old-rose-colored dress from pineapple fibers and dyed with materials originating from coconut husks.[16]

Now there are a lot of designers who are incorporating filipiniana dresses into their creations, adding a modern twist to them. They tailored it to be able to match up to today's ever-changing standards and the needs of everyday people.[17] Although its style has changed, the image of the classic filipina can still be seen.

Gallery

Woman in terno with stiffened "butterfly" sleeves

Woman in terno with stiffened "butterfly" sleeves A young Imelda Marcos wearing terno type of Maria Clara.

A young Imelda Marcos wearing terno type of Maria Clara. Pia Wurtzbach at the Malacañang Palace wearning terno.

Pia Wurtzbach at the Malacañang Palace wearning terno._MET_115249a.jpg.webp) Early 19th century pañuelo in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

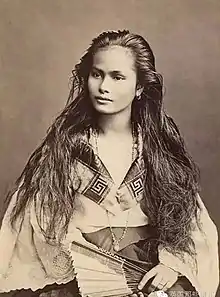

Early 19th century pañuelo in the Metropolitan Museum of Art Mestiza de sangley woman in traje de mestiza with an abaniko fan

Mestiza de sangley woman in traje de mestiza with an abaniko fan

"La Mestisa" (A Filipina Mestiza) by Justiniano Asuncion

"La Mestisa" (A Filipina Mestiza) by Justiniano Asuncion "La Mestisa Española" (A Spanish Mestiza Filipina) by Justiniano Asuncion

"La Mestisa Española" (A Spanish Mestiza Filipina) by Justiniano Asuncion

India A Caballo (Native Filipina On A Horse) by José Honorato Lozano

India A Caballo (Native Filipina On A Horse) by José Honorato Lozano A gown worn by a Meztiza

A gown worn by a Meztiza

See also

References

- Custodio, Arlo (May 27, 2018). "Championing Maria Clara beyond the Walls of Intramuros". The Manila Times. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- "Traje de Mestiza". Philippine Folklife Museum Foundation. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- Moreno, Jose "Pitoy". – Maria Clara, Philippine Costume, koleksyon.com, archived from the original on July 13, 2011.

- "FAST FACTS: Who invented the Philippine terno?". Rappler. January 27, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- Miranda, Pauline (November 15, 2018). "The terno is not our national dress—but it could be". NoliSoil. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- "A Guide to the Philippines' National Costume". Philippine Primer. May 13, 2013. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- "Modern Filipiniana: The 2019 ABS-CBN Ball Dress Code". Metro.style. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- Garcia, Lawrence. "Filipiniana Dresses And How They've Changed Throughout History". Sinta & Co. Filipino Wedding Accessories. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- "The Filipiniana Dress: The Rebirth of the Terno". Vinta Gallery. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- Fashionable Filipinas: An Evolution of the Philippine National Dress in Photographs 1860–1890

- Patterns for the Filipino Dress: From the Traje de Mestiza to the Terno

- Patterns for the Filipino Dress: From the Traje de Mestiza to the Terno

- Patterns for the Filipino Dress by Salvador Bernal & Georgina Encanto

- Fashionable Filipinas: An Evolution of the Philippine National Dress in Photographs 1860–1890 by Gino Gonzales & Mark Lewis Higgins

- Fashionable Fabrics: The Mestiza Dress from the Nineteenth Century to the 1940s by Sandra Castro

- Avendaño, Christine. ‘Modernized’ Maria Clara gown for Arroyo Archived April 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Philippine Daily Inquirer, July 28, 2008.

- The Modernization of the Filipiniana Gown Retrieved January 26, 2019