Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne

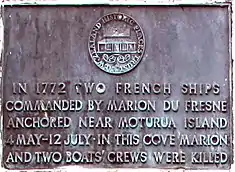

Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne (22 May 1724 – 12 June 1772) was a French privateer, East India captain and explorer. The expedition he led to find the hypothetical Terra Australis in 1771 made important geographic discoveries in the south Indian Ocean and anthropological discoveries in Tasmania and New Zealand. In New Zealand they spent longer living on shore than any previous European expedition. Half way through the expedition's stay Marion died during a military assault by the Ngare Raumati iwi.[1][2]

Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne aka Marion Dufresne | |

|---|---|

| Born | 22 May 1724 Saint Malo, France |

| Died | 12 June 1772 (aged 48) Assassination Cove, Bay of Islands, New Zealand |

| Cause of death | Murder |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation(s) | Explorer, navigator, cartographer |

| Title | Capitaine de frégate |

| Spouse | Julie Bernardine Guilmaut de Beaulieu |

He is commemorated with the toponym Marion Bay, Tasmania, as well in the name of two successive French oceanic research and supply vessel the Marion Dufresne (1972) and the Marion Dufresne II, which service the French Southern Territories of Amsterdam Island, the Crozet Islands, the Kerguelen Islands, and Saint Paul Island.

Early career

Born in Saint Malo in 1724 into the non-noble, but wealthy, Marion family of shipowners and merchants, he eventually inherited a farm 'Le Fresne' near the village of Saint-Jean-sur-Vilaine and styled himself Marion Dufresne (or in some instances Dufresne-Marion). He was never known simply as (or signed himself) 'Du Fresne', but this has become a familiar appellation in New Zealand and Tasmania. He first went to sea in 1741 on a voyage to Cadiz aboard the 22-gun Saint-Ésprit.[3]

During the War of the Austrian Succession Marion commanded several ships as a privateer, including the Prince de Conty where he transported Charles Edward Stuart from Scotland to France.[4] In the Seven Years' War, he was engaged in various naval operations including taking the astronomer Alexandre Guy Pingré to observe the 1761 transit of Venus in the Indian Ocean.[4]

In January 1762 Marion received a grant of 625 argents of land at Quartier Militaire in Mauritius. Although he returned to France in 1764 and 1767, he made the island home in 1768. [5]

Terra Australis expedition

In October 1770 Marion convinced Pierre Poivre, the civil administrator in Port Louis, to equip him with two ships and send him on a twofold mission to the Pacific. Marion's fellow explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville had recently returned from the Pacific with a Tahitian native, Ahutoru. Marion was tasked with returning Ahutoru to his homeland, and then to explore the south Pacific for the hypothetical Terra Australis Incognita.[6] For these purposes Marion was given two ships, the Mascarin and the Marquis de Castries and departed on 18 October 1771.[7]

Marion spent most of his personal fortune on outfitting the expedition with supplies and crew. He hoped to make a significant profit on the journey by trading with the reportedly wealthy islands of the South Pacific.[8] No part of Marion's mission could be achieved; Ahutoru died of smallpox shortly after embarkation, and the expedition did not locate Terra Australis or make a profit from trade.[6] Instead, Marion discovered first the Prince Edward Islands and then the Crozet Islands before sailing towards New Zealand and Australia. His ships spent several days in Tasmania, where Marion Bay in the south-east is named after him. He was the first European to encounter the Aboriginal Tasmanians.[9]

Arrival in New Zealand

Marion sighted New Zealand's Mount Taranaki on 25 March 1772, and named the mountain Pic Mascarin without knowing that James Cook had named it "Mount Egmont" three years earlier.

Over the next month, they repaired their two ships and treated their scurvy, first anchoring at Spirits Bay,[10] and later in the Bay of Islands. Apparently their relations with Māori were peaceful at first; they communicated through the Tahitian vocabulary learned from Ahu-toru and sign language. They befriended many Māori including Te Kauri (Te Kuri) of the Ngāpuhi iwi (tribe). The French established a significant vegetable garden on Moturua Island. Sixty of the French sailors had developed scurvy and were on shore in a tent hospital. They had been invited to visit local Māori at their pa – a very rare event – and had slept there overnight. Māori in return had been invited on board the ships and had slept in the ships overnight. The French officers made a detailed study of the habits and customs of Māori including greetings, sexual mores, fishing methods, the role of females, the making of fern root paste, the killing of prisoners and cannibalism.[11]

In these months there were two instances where Māori were detained. The first had sneaked on board ship and stolen a cutlass. He was detained for a brief period to give him a fright, then released to his friends.[11] Later the Māori made a night raid on the hospital camp taking away many guns and uniforms. While the soldiers chased the raiders, Māori slipped back and stole an anchor.[11] Two men were held as hostage against the return of the stolen goods. One of them admitted he had been involved in the theft but accused Te Kauri of being involved. Marion, finding the men bound, ordered them unbound and released. Later an armed party of Māori approached the French as if to challenge them, but the French understood enough tikanga to make peace with them by exchanging gifts.[11]

Death and reprisals

No French witness to Marion's death survived and it was some time before his crew were aware of his fate. Two contemporary accounts were written by French officers, Jean Roux and Ambroise du Clesmeur.

During the night of 9 June 1772, French sentries at the hospital camp noticed about six Māori prowling. In the morning it was discovered that Māori had also been prowling around a second camp where the French had been making masts. The next day Māori arrived with a present of fish. Roux said the Māori were astonished at the blunderbusses he had mounted outside his tent. He noticed the visiting chief taking a close look at the weapons and how they worked, as well as the defences of the camp, and became suspicious of his motives. The chief asked for the guns to be demonstrated and Roux shot a dog.[11]

That night more Māori were found on Moturua Island prowling around the hospital camp but ran when sentries approached. Captain du Clesmeur alerted Marion to the rise in suspicious activity, but Marion did not listen. On the afternoon of 12 June 1772 Marion and 15 armed sailors went to Te Kauri's village and then went in the captain's gig to go fishing in his favourite fishing area.[13] Marion and 26 men of his crew were killed. Those killed included de Vaudricourt and Pierre Lehoux (a volunteer), Thomas Ballu of Vannes, Pierre Mauclair (the second pilot) from St Malo, Louis Ménager (the steersman) from Lorient, Vincent Kerneur of Port-Louis, Marc Le Garff from Lorient, Marc Le Corre of Auray, Jean Mestique of Pluvigner, Pierre Cailloche of Languidic and Mathurin Daumalin of Hillion.

That night 400 armed Māori suddenly attacked the hospital camp but were stopped in their tracks by the threat of the multiple blunderbusses.[11] Roux held his fire and realised that they had narrowly escaped being killed in their sleep. One chief told Roux that Te Kauri had killed Marion. At this point longboats full of armed French sailors arrived with the news that Marion and the sailors had been killed. One survivor, who had been spared, told them Māori had tricked them into going into the bush, where they had been ambushed, with all the others being killed.[11]

In the following days the French came under relentless attack. The next day about 1,200 Māori surrounded the French, led by Te Kauri. As they approached, Roux ordered Te Kauri shot. Later even more Māori reinforcements arrived. The French decided to abandon the hospital camp. The Māori then stole all the tools and supplies and burnt the camp down. They were close enough that the French could see they were wearing the clothes of Marion and his fellow dead sailors.[11]

The French retreated to Moturua Island. That night Māori again attacked the camp and this time the French opened a general fire. The next day even more Māori arrived taking their forces to about 1,500 men. The French charged this huge force with 26 armed soldiers and put them to flight, the Māori fleeing back to Te Kauri's pa. The French attacked the pa, firing at the defenders, who showered them with spears. The remainder got into canoes and fled. About 250 Māori including five chiefs were killed in the battle. Many of the French were wounded.[11]

Roux, Julien–Marie Crozet and Ambroise Bernard-Marie du Clesmeur took joint command and undertook reprisals against the Māori over a one-month period as the ships were prepared for departure.[14]

A month later on 7 July Roux searched Te Kauri's deserted pa and found a sailor's cooked head on a spike, as well as human bones near a fire.[15] They left on 12 July 1772. The French buried a bottle at Waipoa on Moturua, containing the arms of France and a formal statement taking possession of the whole country, with the name of "France Australe." However, both published and unpublished accounts of Marion's death circulated widely, giving New Zealand a bad reputation as a dangerous land unsuitable for colonisation, and challenged the stereotypes of Pacific Islanders as noble savages then prevalent in Europe.[14]

Possible motives for military assault

There are different possible reasons for the Māori military assault on the landing site, including that the chief Te Kauri (Te Kuri) considered that Marion was a threat to his authority or Te Kauri became concerned at the economic effect of supplying food for the two crews, or that Marion's crew, possibly unwittingly, broke several tapu laws related to their not carrying out the rituals required before the cutting down of kauri trees,[16] or breaking of tapu by fishing in Manawaora Bay.[13]

An account told by a Ngāpuhi elder to John White (ethnographer 1826–1891), but not published until 1965, describes Te Kauri and Tohitapu as leading the military resolution to the landing.[13] Tapu had been placed on Manawaora Bay after members of the local tribe drowned here some time earlier, and their bodies had been washed up at Te Kauri's (Tacoury's sic) Cove. Since the interlopers did not leave, a military resolution was required.[13]

See also

References

- Salmond 1991, pp. 400–401.

- "Marion du Fresne | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- Edward Duyker, Marc-Joseph Marion Dufresne, un marin malouin à la découvertes des mers australes, p. 35

- Salmond 1991, p. 360.

- Edward Duyker, An Officer of the Blue, p. 91

- Beaglehole 1968, pp. cxvi–cxvii

- "Marion du Fresne | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- Salmond 1991, pp. 362–363.

- Edward Duyker, An Officer of the Blue, pp. 126–136

- Whitmore, Robbie. "Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne". New Zealand in History. history-nz.org. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- Diary of Le Clesmeur. Historical records of NZ. Vol 11, Robert McNab

- Meryon, Charles; Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "'The death of Marion du Fresne'". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- "The First Pakehas to Visit The Bay of Islands". Te Ao Hou / The New World. No. 51 (June 1965) pages 14–18. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Quanchi, Max (2005). Historical Dictionary of the Discovery and Exploration of the Pacific Islands. The Scarecrow Press. p. 178. ISBN 0810853957.

- From Tasman to Marsden, R. McNab 1914, Ch 5.

- Hughes, Vicki. "Introduction to Margaret Bullock's Utu: A Story of Love, Hate and Revenge – Fact versus Fiction". New Zealand Electronic Text Collection. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

Bibliography

- Beaglehole, J.C., ed. (1968). The Journals of Captain James Cook on His Voyages of Discovery, vol. I: The Voyage of the Endeavour 1768–1771. Cambridge University Press. OCLC 223185477.

- Edward Duyker (ed.) The Discovery of Tasmania: Journal Extracts from the Expeditions of Abel Janszoon Tasman and Marc-Joseph Marion Dufresne 1642 & 1772, St David's Park Publishing/Tasmanian Government Printing Office, Hobart, 1992, pp. 106, ISBN 0-7246-2241-1.

- Edward Duyker, An Officer of the Blue: Marc-Joseph Marion Dufresne 1724–1772, South Sea Explorer, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1994, pp. 229, ISBN 0-522-84565-7.

- Edward Duyker, Marc-Joseph Marion Dufresne, un marin malouin à la découvertes des mers australes, traduction française de Maryse Duyker (avec l'assistance de Maurice Recq et l'auteur), Les Portes du Large, Rennes, 2010, pp. 352, ISBN 978-2-914612-14-2.

- Edward Duyker, 'Marion Dufresne, Marc-Joseph (1724–1772)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Supplementary Volume, Melbourne University Press, 2005, pp 258–259.

- Kelly, Leslie G. (1951). Marion Dufresne at the Bay of Islands. Wellington: Reed.

- Salmond, Anne (1991). Two worlds : first meetings between Māori and Europeans, 1642–1772. Auckland, N.Z.: Viking. ISBN 0-670-83298-7. OCLC 26545658.

External links

- Marion du Fresne, Marc Joseph, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

- "Marion Dufresne, Marc-Joseph (1724–1772)". Biography – Marc-Joseph Marion Dufresne – Australian Dictionary of Biography. adb.online.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 22 January 2014.