Marsquake

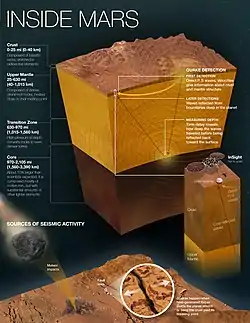

A marsquake is a quake which, much like an earthquake, would be a shaking of the surface or interior of the planet Mars as a result of the sudden release of energy in the planet's interior, such as the result of plate tectonics, which most quakes on Earth originate from, or possibly from hotspots such as Olympus Mons or the Tharsis Montes. The detection and analysis of marsquakes could be informative to probing the interior structure of Mars, as well as identifying whether any of Mars's many volcanoes continue to be volcanically active.[1]

Quakes have been observed and well-documented on the Moon, and there is evidence of past quakes on Venus. Marsquakes were first detected but not confirmed by the Viking mission in 1976.[2] Marsquakes were detected and confirmed by the InSight mission in 2019.[3] Using InSight data and analysis, the Viking marsquakes were confirmed in 2023.[4] Compelling evidence has been found that Mars has in the past been seismically more active, with clear magnetic striping over a large region of southern Mars. Magnetic striping on Earth is often a sign of a region of particularly thin crust splitting and spreading, forming new land in the slowly separating rifts; a prime example of this being the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. However, no clear spreading ridge has been found in this region, suggesting that another, possibly non-seismic explanation may be needed.

The 4,000 km (2,500 mi) long canyon system, Valles Marineris, has been suggested to be the remnant of an ancient Martian strike-slip fault.[5] The first confirmed seismic event emanating from Valles Marineris, a quake with a magnitude of 4.2, was detected by InSight on 25 August 2021, proving it to be an active fault.[6]

Detectability

Mars InSight Lander (May 17, 2022)

The first attempts to detect seismic activity on Mars were with the Viking program with two landers, Viking 1 & 2 in 1976, with seismometers mounted on top of the lander. The seismometer on the Viking 1 lander failed. The Viking 2 seismometer collected data for 2100 hours (89 days) of data over 560 sols of lander recorded.[2][7]

Viking 2 recorded two possible marsquakes on Sol 53 (daytime during windy period) and Sol 80 (nighttime during low wind period). Due to the inability to separate ground motion from wind-driven lander vibrations and the lack of other collaborating possible marsquakes, the Sol 53 and Sol 80 events could not be confirmed during the Viking mission.[7][8] It was possible to rule out frequent and large marsquakes at that time.[9] The low detection rate and evaluation when the windspeed was low at the Viking 2 site, allowed limits to be placed on seismic activity on Mars.[10][7]

In 2013, data from the InSight mission (see below) led to an increased interest in the Viking data set, and further analysis may reveal one of the largest collection of Mars dust devil detections.[7] In 2023, a re-evaluation of Viking 2 using InSight data and analysis, and Viking wind data, confirmed that the two Viking events on Sol 53 and 80 were marsquakes.[4]

The InSight Mars lander, launched in May 2018, landed on Mars on 26 November 2018 and deployed a seismometer called Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) on 19 December 2018 to search for marsquakes and analyze Mars's internal structure. Even if no seismic events are detected, the seismometer is expected to be sensitive enough to detect possibly several dozen meteors causing airbursts in Mars's atmosphere per year, as well as meteorite impacts.[11] It will also investigate how the Martian crust and mantle respond to the effects of meteorite impacts, which gives clues to the planet's inner structure.[12][13][14]

.jpg.webp)

A faint seismic signal, believed to be a small marsquake, was measured and recorded by the InSight lander on 6 April 2019.[15] The lander's seismometer detected ground vibrations while three distinct kinds of sounds were recorded, according to NASA. Three other events were recorded on 14 March, 10 April, and 11 April, but these signals were even smaller and more ambiguous in origin, making it difficult to determine their cause.[16][17]

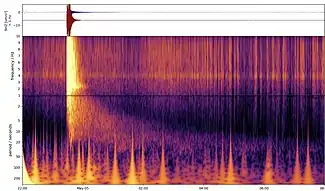

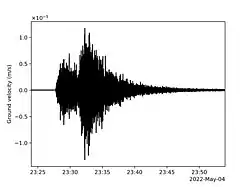

On 4 May 2022, a large marsquake, estimated at magnitude 5, was detected by the seismometer on the InSight lander.[18] In October 2023 the results of a a colaborative international project to scan the surface of Mars for a new impact crater created at the time of the 4 May 2022 seismic event, known as S1222a, was published. It was estimated that a crater of at least 300m in diameter would be created to produce the seismic waves, which reverburated round the planet for six hours. The survey of satelitte images from five different orbiters concluded that the event was not the result of an impact event.[19]

Candidate natural seismic events

Despite the drawbacks of significant wind interference, on Sol 80 of the Viking 2 lander's mission (roughly November 23, 1976), the on-board seismometer detected an unusual acceleration event during a period of relatively low wind speed. Based on the features of the signal and assuming Mars's crust behaves similar to Earth's crust near the lander's testing site in Southern California, the event was estimated to have a Richter magnitude of 2.7 at a distance of roughly 110 kilometers.[2] However, the wind speed was only measured 20 minutes previously, and 45 minutes after, at 2.6 and 3.6 meters per second, respectively. While a sudden wind gust of 16 m/s would have been required to produce the event, it could not be completely ruled out.[20] The Sol 80 event was later identified as a marsquake.[4] The earlier Sol 53 event initially received much interest as a possible marsquake, but was correlated with wind and not considered further.[2] Following the re-evaluation of the Sol 80 event as a marsquake, a re-evaluation of the Sol 53 event showed that it was unique among all Viking daytime recorded waveforms and the only one with a waveform with a rapid rise time and duration similar to Sol 80. Consequently Sol 53 was identified as a marsquake. Comparing Viking with InSight events, using technologies 43 years apart is challenging, but comparison of the two Viking events with some InSight events showed that the similarity of waveforms was reasonable.[4]

On Sol 128 of the InSight lander mission the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) detected one magnitude 1–2 seismic event on April 6, 2019.[21] Three other unconfirmed candidate seismic events were detected on March 14, April 10 and April 11, 2019. The quake is similar to moonquakes detected during the Apollo program. It could have been caused by activity internal to the planet or by a meteorite striking the surface. The epicenter was believed to be within 100 km of the lander. As of 30 September 2019, SEIS had reported 450 events of various types.[22]

Experimental (artificial) seismic events

NASA's Mars Perseverance Rover will act as a seismic source of known temporal and spatial localization as it lands on the surface. The InSight lander will evaluate whether the signals produced by this event will be detectable by 3,452 km away.[23]

See also

- Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS, instrument on InSight Mars lander)

- Tectonics of Mars

- Volcanology of Mars

References

- Kornei, Katherine (22 January 2022). "Bouncing Boulders Point to Quakes on Mars – A preponderance of boulder tracks on the red planet may be evidence of recent seismic activity". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- Anderson, Don L.; Miller, W. F.; Latham, G. V.; Nakamura, Y.; Toksoz, M. N.; Dainty, M. N.; Duennebier, F. K.; Lazarewicz, A. R.; Kovach, R. L.; Knight, T. C. D. (September 30, 1977). "Seismology on Mars". Journal of Geophysical Research. 82 (28): 22 – via American Geophysical Union.

- Greicius, Tony (2021-04-01). "NASA's InSight Detects Two Sizable Quakes on Mars". NASA. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- Lazarewicz, Andrew R. (10 July 2023). "Viking Marsquakes 1976 -- Seismic Archaeology". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 128 (e2022JE007660): 20 – via American Geophysical Union.

- Yin, A. (4 June 2012). "Structural analysis of the Valles Marineris fault zone: Possible evidence for large-scale strike-slip faulting on Mars". Lithosphere. 4 (4): 286–330. Bibcode:2012Lsphe...4..286Y. doi:10.1130/L192.1.

- "Two Largest Marsquakes To Date Recorded From Planet's Far Side". Seismological Society of America (Press release). SpaceRef. 26 April 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- Lorenz, Ralph D.; Nakamura, Yosio (2013). "Viking Seismometer Record: Data Restoration and Dust Devil Search" (PDF). 44th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2013) (1719): 1178. Bibcode:2013LPI....44.1178L. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- Greicius, Tony (28 March 2018). "'Marsquakes' Could Shake Up Planetary Science". NASA. NASA. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- Lorenz, Ralph D.; Nakamura, Yosio; Murphy, James R. (November 2017). "Viking-2 Seismometer Measurements on Mars: PDS Data Archive and Meteorological Applications". Earth and Space Science. 4 (11): 681–688. Bibcode:2017E&SS....4..681L. doi:10.1002/2017EA000306.

- Goins, N. R.; Lazarewicz, A. R. (May 1979). "Martian Seismicity". Geophysical Research Letters. 6 (7): 3 – via American Geophysical Union.

- Stevanović, J.; Teanby, N. A.; Wookey, J.; Selby, N.; Daubar, I. J.; Vaubaillon, J.; Garcia, R. (9 January 2017). "Bolide Airbursts as a Seismic Source for the 2018 Mars InSight Mission". Space Science Reviews. 211 (1–4): 525–545. Bibcode:2017SSRv..211..525S. doi:10.1007/s11214-016-0327-3. S2CID 125102926.

- "NASA and French Space Agency Sign Agreement for Mars Mission" (Press release). NASA. 10 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- Boyle, Rebecca (4 June 2015). "Listening to meteorites hitting Mars will tell us what's inside". New Scientist. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- Kumar, Sunil (1 September 2006). Design and development of a silicon micro-seismometer (PDF) (Ph.D.). Imperial College London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- Witze, Alexandra (24 April 2019). "First "Marsquake" Detected on Red Planet". Scientific American. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- Brown, Dwayne; Johnson, Alana; Good, Andrew (23 April 2019). "NASA's InSight Detects First Likely 'Quake' on Mars". NASA. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- Bartels, Meghan (23 April 2019). "Marsquake! NASA's InSight Lander Feels Its 1st Red Planet Tremor". Space.com. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- Good, Andrew; Fox, Karen; Johnson, Alana (9 May 2022). "NASA's InSight Records Monster Quake on Mars". NASA. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- "Source of largest ever Mars quake revealed". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- Lorenz, Ralph D.; Nakamura, Yosio; Murphy, James R. (November 2017). "Viking-2 Seismometer Measurements on Mars: PDS Data Archive and Meteorological Applications". Earth and Space Science. 4 (11): 681–688. Bibcode:2017E&SS....4..681L. doi:10.1002/2017ea000306. ISSN 2333-5084.

- Amos, Jonathan (23 April 2019). "Nasa lander 'detects first Marsquake'". BBC. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- Banerdt, W. Bruce; Smrekar, Suzanne E.; Banfield, Don; Giardini, Domenico; Golombek, Matthew; Johnson, Catherine L.; Lognonné, Philippe; Spiga, Aymeric; Spohn, Tilman; Perrin, Clément; Stähler, Simon C. (March 2020). "Initial results from the InSight mission on Mars". Nature Geoscience. 13 (3): 183–189. Bibcode:2020NatGe..13..183B. doi:10.1038/s41561-020-0544-y. ISSN 1752-0894. S2CID 211266334.

- Fernando, Benjamin; Wójcicka, Natalia; Marouchka, Froment; Maguire, Ross; Stähler, Simon; Rolland, Lucie]; Collins, Gareth; Karatekin, Ozgur; Larmat, Carene; Sansom, Eleanor; Teanby, Nicholas; Spiga, Aymeric; Karakostas, Foivos; Leng, Kuangdai; Nissen-Meyer, Tarje; Kawamura, Taichi; Giardini, Domenico; Lognonné, Philippe; Banerdt, Bruce; Daubar, Ingrid (April 2021). "Listening for the landing: Seismic detections of Perseverance's arrival at Mars with InSight". Earth and Space Science. 8 (4). doi:10.1029/2020EA001585. ISSN 2333-5084.

External links

- Video (2:48) – MarsQuakes on YouTube NASA (19 July 2019)