Battle of Praga

The Battle of Praga or the Second Battle of Warsaw of 1794, also known in Russian and German as the storming of Praga[9] (Russian: Штурм Праги) and in Polish as the defense of Praga (Polish: Obrona Pragi), was a Russian assault on Praga, the easternmost community of Warsaw, during the Kościuszko Uprising in 1794. It was followed by a massacre (known as the Massacre of Praga[lower-alpha 4]) of the civilian population of Praga.

| Battle of Praga | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Kościuszko Uprising | |||||||

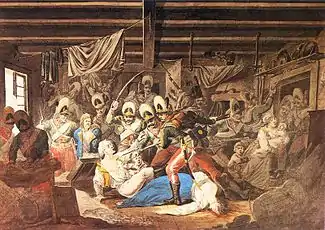

Obrona Pragi, Aleksander Orłowski | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

22,000[2][3][4][5][6] 86 cannons[2][6] |

30,000[5][3][2][6][1]

104 cannons[2][6] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,540-2,000 killed and wounded[2][8][1] |

9,000-10,000 killed, died of wounds and drowned (excluding civilians)[1] | ||||||

| 12,000 Polish civilians killed[lower-alpha 3] | |||||||

_1794.PNG.webp)

Praga is a suburb ("Faubourg") of Warsaw, lying on the right bank of the Vistula river. In 1794 it was well fortified and was better strengthened than the western part of the capital, located on the left bank of the Vistula.

Eve of the battle

Previous events

Russian commander Alexander Suvorov inflicted a series of defeats on the rebels: the Battle of Krupczyce on 17 September, where Suvorov's 13,000 soldiers were opposed by 5,000 Polish;[10] the Battle of Brest on 19 September,—9,000 Russians fought here against 16,000 Poles; and the Battle of Kobyłka on 26 October, with 7,000 Russians ran into 5,560 Polish forces.[11] After the Battle of Maciejowice, General Tadeusz Kościuszko was captured by Russians.[12]: 210 The internal struggle for power in Warsaw and the demoralisation of the city's population prevented General Józef Zajączek from finishing the fortifications surrounding the city both from the east and from the west. At the same time, the Russians were making their way towards the city.

Opposing forces

The Russian forces consisted of two battle-hardened corps under Generals Alexander (Aleksandr) Suvorov and Ivan Fersen. Suvorov took part in the recent Russo-Turkish war, then in the heavy fighting in Polesie. Fersen fought for several months in Poland but was also joined by fresh reinforcements sent from Russia. Each of them had approximately 11,000 men.

The Polish-Lithuanian forces consisted of a variety of troops. Apart from the rallied remnants of the Kościuszko's army defeated in the Battle of Maciejowice, it also included a large number of untrained militia from Warsaw, Praga and Vilnius, a 500-man Jewish regiment of Berek Joselewicz as well as a number of scythemen (2,000 men[13]) and civilians,[14][15] plus 5,000 regular cavalry. The total number of irregulars was to be about 12,000 and the regular troops about 18,000.[13] One of the sources claims 15,000 regular infantry and only 2,500 cavalry (17,500 regulars altogether).[16] The forces were organised in three separate lines, each covering a different part of Praga. The central area was commanded directly by General Józef Zajączek, the northern area was commanded by Jakub Jasiński and the southern by Władysław Jabłonowski. Altogether, Warsaw was defended by 30,000 men[5][2][3][16] and had 104 cannons.[2][6] Suvorov came to the walls of Praga from his camp at Kobyłka with 16,000[3][4][5] to 18,000[lower-alpha 5] footsore troops (regulars) and 86 cannons.[2][6] Suvorov also had 4,000 regular cavalry and 2,000 irregular Cossack cavalry at the assault.[13] The total number of regular troops was up to 25,000 with as many as 7,000 regular cavalrymen; Cossacks were up to 5,000[17] – these were the corps of Derfelden, Potemkin, Fersen, and Shevich's reserve.[18] That is, the forces may have been roughly equal overall, however, largely due to the declining morale of the Varsovians, they put up just 2,000 men — irregular soldiers — to defend the ramparts. The main force, the regular troops, stood behind fortifications as a reserve on the vast field according to Kościuszko's plan.[19] After a reconnaissance by the Russian side, up to 24,055 men, inclusive of 41 infantry battalions and 81 cavalry squadrons, would come out for the storming together with reserve units;[18] in the village of Okuniew a wagenburg was stationed.[20]

Battle

The Russian forces reached the outskirts of Warsaw on 2 November 1794, pushing back Polish-Lithuanian outposts. Immediately upon arrival, they started preparing artillery batteries and in the morning of 3 November started an artillery barrage of the Polish-Lithuanian defences. This made Józef Zajączek think that the opposing forces were preparing for a long siege. However, Suvorov's plan assumed a fast and concentrated assault on the defences rather than a bloody and lengthy siege.

At 3 o'clock in the morning of November 4, the Russian troops silently reached the positions just outside the outer rim of the field fortifications and two hours later started an all-out assault. The defenders were completely surprised and soon the defence lines were broken into several isolated pockets of resistance, bombarded by the Russians with canister shots with a devastating effect. General Zajączek was slightly wounded and retreated from his post, leaving the remainder of his forces without a single command. General Wawrzecki tried to stop the fleeing Polish regiments, but it was all for nothing.[21] This made the Poles and Lithuanians retreat towards the centre of Praga and then towards Vistula.

The heavy fighting lasted for four hours and resulted in a complete defeat of the Polish-Lithuanian forces. Joselewicz survived, being severely wounded, but almost all of his command was annihilated; Jasiński was killed fighting bravely on the front line. Only a small part managed to evade encirclement and retreated to the other side of the river across a bridge; hundreds of soldiers and civilians fell from a bridge and drowned in the process.

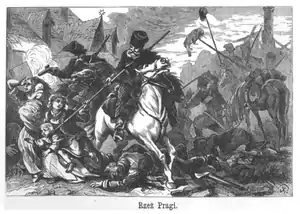

Massacre

After the battle ended, the Russian troops, against the orders given by Suvorov before the battle, started to loot and burn the entire borough of Warsaw in revenge for the slaughter of the Russian Garrison in Warsaw[22] during the Warsaw Uprising in April 1794, when about 2,000 Russian soldiers died.[23] Faddey Bulgarin recalled the words of General Ivan von Klugen, who took part in the Battle of Praga,

"We were being shot at from the windows of houses and the roofs, and our soldiers were breaking into the houses and killing all who happened to get in the way… In every living being our embittered soldiers saw the murderer of our men during the uprising in Warsaw… It cost a lot of effort for the Russian officers to save these poor people from the revenge of our soldiers… At four o'clock the terrible revenge for the slaughter of our men in Warsaw was complete!"[24]

Almost all of the area was pillaged and inhabitants of the Praga district were tortured, raped and murdered. The exact death toll of that day remains unknown, but it is estimated that up to 20,000 people were killed,[5][25] including military and civilians. Suvorov himself wrote: "The whole of Praga was strewn with dead bodies, blood was flowing in streams."[26] It was thought that unruly Cossack troops were partly to blame for the uncontrolled destruction.[27] Russian historians (e.g., Boris Kipnis) state that Suvorov tried to stop the massacre by ordering the destruction of the bridge to Warsaw over the Vistula river with the purpose of preventing the spread of violence to the capital,[1][28] although Polish historians dispute this, pointing out to purely military considerations of this move, such as to stop Polish and Lithuanian troops stationing on the left bank from attacking Russian soldiers.[29] Kipnis asserted that when Suvorov learned of the civilian bloodshed, he immediately rode to Praga, but when he received the news, it was too late—the blood of innocent had been spilled, and spilled a lot; nevertheless, Suvorov brought the soldiers to their senses and stopped the massacre.

Aftermath

Russian casualties were 1,540 killed and wounded. Other estimate 2,000 dead and wounded. Poland suffered losses of some 9,000 to 10,000 killed, wounded, and drowned, as well as 11,000 to 13,000 taken prisoner. According to other estimates, the Poles suffered 8,000 killed[1] and 14,680 captured.[2][5][3][4] After the battle the commanders of Warsaw and large part of its inhabitants became demoralised. To spare Warsaw the fate of its eastern suburb, General Tomasz Wawrzecki decided to withdraw his remaining forces southwards and on November 5. Warsaw was captured by the Russians with little or no opposition. It is said that after the battle General Aleksandr Suvorov sent a report to Catherine the Great consisting of only four words: Hooray! Warsaw is ours! The Empress of Russia replied equally briefly: Bravo Fieldmarshal, Catherine,[30] promoting him to Field Marshal for this victory.[23] The massacre of Praga dented Suvorov and the Russian army's reputation throughout Europe.[31]

National historiographies

Russian writers and historians have tried to either justify or present this massacre as an revenge for Polish conquest of Moscow in 1612 or the heavy losses Russian garrison sustained during the Warsaw Uprising of 1794.[23][29] Such reasoning was immortalized after 1831 when Russians once again crushed a Polish uprising (the November Uprising) against Russia's occupation of Poland; shortly afterward Alexander Pushkin compared the Praga massacre with the events of events of 1612: "Once, you celebrated the shame of Kreml, tsar's enslavement. But so did we crushed infants on Praga's ruins".[29][32] Similar sentiments can be seen in the poetry of Vasily Zhukovsky and Gavrila Derzhavin or plays of Mikhail Kheraskov and Michail Glinka.[29] On the other hand Polish literature and historiography has a tendency to be biased in the other direction, dwelling on the description of Russian cruelty and barbarism.[29]

Similar arguments were used by Russian historians Pyotr Chaadayev, Anton Kozachenko and even Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and can be seen repeated in the Soviet-era reference works as the Great Soviet Encyclopedia.[29] After the Second World War this entire event, like many other cases of Russo-Polish conflicts, was a taboo topic in the Soviet Bloc, where Soviet propaganda now tried to create an illusion of eternal Slavic unity and friendship. Any references to the massacre of Praga were eliminated from textbooks, existing academic references were restricted and censored, and further research was strongly discouraged.[33] Although after the fall of communism the restrictions to research were lifted, this is still one of the controversial and sensitive topic in the Polish-Russian relations.[34]

See also

Notes and references

-

- 2 November (O.S. 22 November): pushing back Polish pickets (outposts) by the Russian troops, reconnaissance of Suvorov, troop disposition, and the erection of artillery batteries (the Russians erected batteries to disguise the forthcoming attack in order to give the rebels reason to expect a siege);

- 3 November (O.S. 23 November): Russian bombardment, a substantial artillery duel in which the rebels performed well;

- 4 November (O.S. 24 November): Russian assault on the suburb.

- Of the men taken alive and wounded, more than 6,000 were sent home; up to 4,000 were sent to Kiev, – from the regular army, without the scythemen, who were set at liberty with other non-military men.[1]

- Petrushevsky: "According to a Polish source, 8,000 Poles in arms and 12,000 Praga residents killed."[1]

- The Polish term for the massacre, rzeź Pragi, more literally translates as Slaughter of Praga, but most English sources translate it as "massacre".

- All the troops the Russians could muster amounted to 18,000 men.[17]

- Petrushevsky, Alexander (1884). Generalissimo Prince Suvorov (in Russian). Vol. 2 (1st ed.). Типография М. М. Стасюлевича. pp. 99–125.

- Encyclopædia Britannica: or, A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature, Volume I, Part 1. A. Bell and C. Macfarquhar, 1797. P. 634

- Duffy C. Eagles Over the Alps: Suvorov in Italy and Switzerland, 1799. Emperor's Press, 1999. P. 16

- Dixon S. The Modernisation of Russia, 1676-1825. Cambridge University Press. 1999. P. 41

- Duffy C. Russia's Military Way to the West: Origins and Nature of Russian Military Power 1700-1800. Routledge. 2015. P. 196

- History of the Eighteenth Century and of the Nineteenth Till the Overthrow of the French Empire. Volume VI. Chapman and Hall. 1845. P. 256

- See Opposing forces subsection

- (in Russian) Бантыш-Каменский Д. Биографии российских генералиссимусов и генерал-фельдмаршалов. СПб.: В тип. 3-го деп. Мингосимуществ,1840;

- Bodart, Gaston (1908). Militär-historisches Kriegs-Lexikon (1618-1905) (in German). Vienna & Leipzig: C. W. Stern. p. 300. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- See pl:Bitwa pod Krupczycami

- See pl:Bitwa pod Kobyłką

- Storozynski, A., 2009, The Peasant Prince, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 9780312388027

- Arsenyev & Petrushevsky 1898.

- Tgnacy Schipper, Żydzi Krolestwa Polskiego w dobie Powstania Listopadowego, Warszawa, 1932.

- Orlov 1894, pp. 70–71.

- Prof. Korobkov, Nikolay Mikhailovich (2009). "Польская война 1794 года в реляциях и рапортах А. В. Суворова" [The Polish war of 1794 in the dispatches and reports of A. V. Suvorov]. Военная история 2-й половины 18 века (in Russian). Moscow: "Красный архив", No. 4. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- Orlov 1894, p. 72.

- Orlov 1894, pp. 75–76.

- Orlov 1894, p. 70.

- Orlov 1894, p. 73.

- Orlov 1894, p. 88.

- Madariaga: Catherine the Great: a Short History (Yale) p.175

- John T. Alexander, Catherine the Great: Life and Legend, Oxford University Press US, 1999, ISBN 0-19-506162-4, Google Print, p.317

- Faddey Bulgarin (21 August 2015). Воспоминания [Memoires] (in Russian). Российский Мемуарий.

- "According to one Russian estimate 20,000 people had been killed in the space of a few hours" (Adam Zamoyski: The Last King of Poland, London, 1992 p.429)

- Isabel de Madariaga, Russia in the Age of Catherine the Great, Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2002, ISBN 1-84212-511-7, Google Print, p.446

- John Leslie Howard, Soldiers of the Tsar: Army and Society in Russia, 1462-1874, Keep, Oxford University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-19-822575-X, Google Print, p.216

- Denis Dawidow (31 March 2009). ВСТРЕЧА С ВЕЛИКИМ СУВОРОВЫМ. Lib.ru/Классика (in Russian).

- Janusz Tazbir, Polacy na Kremlu i inne historyje (Poles on Kreml and other stories), Iskry, 2005, ISBN 83-207-1795-7, fragment online Archived March 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Norman Davies, Europe: A History, Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-19-820171-0, Google Print, p.722

- Madariaga: Catherine the Great p.175

- Dixon, Megan (2005). "Repositioning Pushkin and Poems of the Polish Uprising". In Ransel, David L.; Shallcross, Bozena; Shallcross, Bożena (eds.). Polish Encounters, Russian Identity. Indiana University Press. pp. 58–61. ISBN 978-0-253-21771-4.

- Marc Ferro, The Use and Abuse of History: Or How the Past Is Taught to Children, Routledge, 2003, ISBN 0415285925, Google Print, p.259

- Norman Davies, God's Playground, Columbia University Press, 1984, ISBN 0231053517 Google Print, p.571

Sources

- Orlov, Nikolay Aleksandrovich (1894). Штурм Праги Суворовым в 1794 году [The storming of Praga by Suvorov in 1794] (in Russian). St. Petersburg: Типография Штаба войск Гвардии и Петербургского военного округа. ISBN 978-5-4460-5018-5. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- Arsenyev, Konstantin; Petrushevsky, Fyodor (1898). Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (in Russian). Vol. XXIVa: "Полярные сияния — Прая". Friedrich A. Brockhaus (Leipzig), Ilya A. Efron (St. Petersburg). p. 934. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

External links

- 04.11.1794. Battle of Praga, Suvorov's Corps OOB

- The hand-written sketch map of storm of Praga, suburb of Warsaw. 1794.

- (in Polish) 4 listopada 1794 r. O jeden most za mało, Gazeta Wyborcza, 2007-11-06