Maui

The island of Maui (/ˈmaʊi/; Hawaiian: [ˈmɐwwi])[3] is the second-largest island of the state of Hawaii at 727.2 square miles (1,883 km2), and the 17th-largest island in the United States.[4] Maui is the largest of Maui County's four islands, which also include Molokaʻi, Lānaʻi, and unpopulated Kahoʻolawe. In 2020, Maui had a population of 168,307, the third-highest of the Hawaiian Islands, behind Oʻahu and Hawaiʻi Island. Kahului is the largest census-designated place (CDP) on the island, with a population of 28,219 as of 2020,[5] and the island's commercial and financial hub.[6] Wailuku is the seat of Maui County and is the third-largest CDP as of 2010. Other significant places include Kīhei (including Wailea and Makena in the Kihei Town CDP, the island's second-most-populated CDP), Lāhainā (including Kāʻanapali and Kapalua in the Lāhainā Town CDP), Makawao, Pukalani, Pāʻia, Kula, Haʻikū, and Hāna.

Nickname: The Valley Isle | |

|---|---|

Landsat satellite image of Maui. The small island to the southwest is Kahoʻolawe. | |

Small-scale map of the island and location in the state of Hawaii | |

| Geography | |

| Location | 20°48′N 156°18′W |

| Area | 727.2 sq mi (1,883 km2) |

| Area rank | 2nd largest Hawaiian island |

| Highest elevation | 10,023 ft (3055 m)[1] |

| Highest point | Haleakalā |

| Administration | |

United States | |

| Symbols | |

| Flower | Lokelani |

| Color | ʻĀkala (pink) |

| Largest settlement | Kahului |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | Mauian |

| Population | 164,221 (2021) |

| Pop. density | 162/sq mi (62.5/km2) |

Etymology

Native Hawaiian tradition gives the origin of the island's name in the legend of Hawaiʻiloa, the navigator credited with discovering the Hawaiian Islands. According to it, Hawaiʻiloa named the island after his son, who in turn was named for the demigod Māui. Maui's previous name was ʻIhikapalaumaewa.[7] The Island of Maui is also called the "Valley Isle" for the large isthmus separating its northwestern and southeastern volcanic masses.

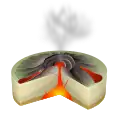

Geology and topography

Maui's diverse landscapes are the result of a unique combination of geology, topography, and climate. Each volcanic cone in the chain of the Hawaiian Islands is built of basalt, a dark, iron-rich/silica-poor rock, which poured out of thousands of vents as highly fluid lava over millions of years. Several of the volcanoes were close enough to each other that lava flows on their flanks overlapped one another, merging into a single island. Maui is such a "volcanic doublet," formed from two shield volcanoes that overlapped one another to form an isthmus between them.[8]

.jpg.webp)

The older, western volcano has been eroded considerably and is cut by numerous drainages, forming the peaks of the West Maui Mountains (in Hawaiian, Mauna Kahalawai). Puʻu Kukui is the highest of the peaks at 5,788 ft (1,764 m). The larger, younger volcano to the east, Haleakalā, rises to 10,023 ft (3,055 m) above sea level, and measures 5 mi (8.0 km) from seafloor to summit.

The eastern flanks of both volcanoes are cut by deeply incised valleys and steep-sided ravines that run downslope to the rocky, windswept shoreline. The valley-like Isthmus of Maui that separates the two volcanic masses was formed by sandy erosional deposits.

Maui's last eruption (originating in Haleakalā's Southwest Rift Zone) likely occurred between 1480 and 1600;[9] the resulting lava flows are located at Cape Kīnaʻu between ʻĀhihi Bay and La Perouse Bay on the southwest shore of East Maui. Considered to be dormant by volcanologists, Haleakalā is thought to be capable of further eruptions.[10]

Maui is part of a much larger unit, Maui Nui, that includes the islands of Lānaʻi, Kahoʻolawe, Molokaʻi, and the now submerged Penguin Bank. During periods of reduced sea level, including as recently as 200,000 years ago,[11] they are joined as a single island due to the shallowness of the channels between them.

Climate

The climate of the Hawaiian Islands is characterized by a two-season year, tropical and uniform temperatures everywhere (except at high elevations), marked geographic differences in rainfall, high relative humidity, extensive cloud formations (except on the driest coasts and at high elevations), and dominant trade wind flow (especially at elevations below a few thousand feet). Maui itself has a wide range of climatic conditions and weather patterns that are influenced by several different factors in the physical environment:

- Half of Maui is situated within 5 mi (8.0 km) of the island's coastline. This, and the extreme insularity of the Hawaiian Islands account for the strong marine influence on Maui's climate.

- Gross weather patterns are typically determined by elevation and orientation towards the Trade winds (prevailing air flow comes from the northeast).

- Maui's rugged, irregular topography produces marked variations in conditions. Air swept inland on the Trade winds is shunted one way or another by the mountains, valleys, and vast open slopes. This complex three-dimensional flow of air results in striking variations in wind speed, cloud formation, and rainfall.

Maui displays a unique and diverse set of climatic conditions, each of which is specific to a loosely defined sub-region of the island. These sub-regions are defined by major physiographic features (such as mountains and valleys) and by location on the windward or leeward side of the island.

| Climate data for Maui | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) | 76.3 (24.6) |

75.5 (24.2) |

75.3 (24.1) |

75.9 (24.4) |

76.8 (24.9) |

77.7 (25.4) |

78.6 (25.9) |

79.3 (26.3) |

80 (26.7) |

80 (26.7) |

78.9 (26.1) |

77.1 (25.1) | |

| Source: meteodb.com[12] | |||||||||||||

Subregions

- Windward lowlands – Below 2,000 ft (610 m) on north-to-northeast sides of an island. Roughly perpendicular to the direction of prevailing trade winds. Moderately rainy; frequent trade wind-induced showers. Skies are often cloudy to partly cloudy. Air temperatures are more uniform (and mild) than those of other regions.

- Leeward lowlands – Daytime temperatures are a little higher and nighttime temperatures are lower than in windward locations. Dry weather is prevalent, except for sporadic showers that drift over the mountains to windward and during short-duration storms.

- Interior lowlands – Intermediate conditions, often sharing characteristics of other lowland sub-regions. Occasionally experience intense local afternoon showers from well-developed clouds that formed due to local daytime heating.

- Leeward side high-altitude mountain slopes with high rainfall – Extensive cloud cover and rainfall all year long. Mild temperatures are prevalent, but humidity is higher than in any other sub-region.

- Leeward side lower mountain slopes – Rainfall is higher than on the adjacent leeward lowlands but much less than at similar altitudes on the windward side; however, maximum rainfall usually occurs leeward of the crests of lower mountains. Temperatures are higher than on the rainy slopes of the windward sides of mountains; cloud cover is almost as extensive.

- High mountains – Above about 5,000 ft (1,500 m) on Haleakalā, rainfall decreases rapidly with elevation. Relative humidity may be ten percent or less. The lowest temperatures in the state are experienced in this region: air temperatures below freezing are common.

Rainfall

Showers are very common; while some of these are very heavy, the vast majority are light and brief. Even the heaviest rain showers are seldom accompanied by thunder and lightning. Throughout the lowlands in summer an overwhelming dominance of trade winds produces a drier season. At one extreme, the annual rainfall averages 17 in (430 mm) to 20 in (510 mm) or less in leeward coastal areas,side such eye as the shoreline from Maalaea Bay to Kaupo, and near the summit of Haleakalā. At the other extreme, the annual average rainfall exceeds 300 in (7,600 mm) along the lower windward slopes of Haleakalā, particularly along the Hāna Highway. Big Bog, a spot on the edge of Haleakala National Park overlooking Hana at about 5,400 ft (1,600 m) elevation had an estimated mean annual rainfall of 404 in (10,300 mm) over the 30-year period of 1978 to 2007.[13] If the islands of the State of Hawaii did not exist, the average annual rainfall on the same patch of water would be about 25 in (640 mm). Instead, the mountainous topography of Maui and the other islands induce an actual average of about 70 in (1,800 mm).

- Daily variations

| Maui | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the lowlands, rainfall is most likely to occur throughout the year during the night or morning hours, and least likely in mid-afternoon. The most pronounced daily variations in rainfall occur during the summer because most summer rainfall consists of trade winds showers that most often occur at night. Winter rainfall in the lowlands is the result of storm activity, which is as likely to occur in the daytime as at night. Rainfall variability is far greater during the winter when occasional storms contribute appreciably to rainfall totals. With such wide swings in rainfall, there are inevitably occasional droughts, sometimes causing economic losses. These occur when winter rains fail to produce sufficient significant rainstorms, impacting normally dry areas outside the trade winds that depend on them the most. The winter of 2011–2012 produced extreme drought on the leeward sides of Moloka'i, Maui, and the Island of Hawaii.

Microclimates

.jpg.webp)

The blend of warm tropical sunshine, varying humidity, ocean breezes and trade winds, and varying elevations create a variety of microclimates. Although the island of Maui is fairly small, it can feel quite different in each district resulting in a unique selection of microclimates that are typical to each of its distinctive locations: Central Maui; leeward South Maui, and West Maui; windward North Shore and East Maui; and Upcountry Maui.

Maui's daytime temperatures average between 75 °F (24 °C) and 90 °F (32 °C) year round, while evening temperatures are about 15 °F (8.3 °C) cooler in the more humid windward areas, about 18 °F (10 °C) cooler in the drier leeward areas, and cooler yet in higher elevations.

.jpg.webp)

Central Maui consists primarily of Kahului and Wailuku. Kahului is the center of the island and tends to keep steady, high temperatures throughout the year. The microclimate in Kahului can be at times muggy, but it usually feels relatively dry and is often very breezy. The Wailuku area is set closer to the West Maui Mountain range. Here, more rainfall will be found throughout the year and higher humidity levels.

Leeward side includes South Maui (Kihei, Wailea, and Makena) and West Maui (Lahaina, Kaanapali, and Kapalua). These areas are typically drier, with higher daytime temperatures (up to 92 °F (33 °C)), and the least amount of rainfall. (An exception is the high-altitude, unpopulated West Maui summit, which boasts up to 400 in (10,000 mm) of rainfall per year on its north and east side.)

.jpg.webp)

Windward side includes the North Shore (Paia and Haiku) and East Maui (Keanae, Hana, and Kipahulu). Located in the prevailing, northeast trade winds, these areas have heavier rainfall levels, which increase considerably at higher elevations.

Upcountry Maui (Makawao, Pukalani, and Kula) at the 1,500 ft (460 m) to 4,500 ft (1,400 m) levels, provides mild heat (70 °F (21 °C) and low 80 °F (27 °C)) during the day and cool evenings. The higher the elevation, the cooler the evenings. During Maui's winter, Upper Kula can be as cold as 40 °F (4 °C) in the early morning hours, and the Haleakala summit can dip below freezing.

An exception to the normal pattern is the occasional winter "Kona storms" which bring rainfall to the South and West areas accompanied by high southwesterly winds (opposite of the prevailing trade wind direction).

Natural history

Maui is a leading whale-watching center in the Hawaiian Islands due to humpback whales wintering in the sheltered ʻAuʻau Channel between the islands of Maui county. The whales migrate approximately 3,500 mi (5,600 km) from Alaskan waters each autumn and spend the winter months mating and birthing in the warm waters off Maui, with most leaving by the end of April. The whales are typically sighted in pods: small groups of several adults, or groups of a mother, her calf, and a few suitors. Humpbacks are an endangered species protected by U.S. federal and Hawaiʻi state law. There are estimated to be about 22,000 humpbacks in the North Pacific.[15] Although Maui's Humpback face many dangers, due to pollution, high-speed commercial vessels, and military sonar testing, their numbers have increased rapidly in recent years, estimated at 7% growth per year.[16]

Maui is home to a large rainforest on the northeastern flanks of Haleakalā, which serves as the drainage basin for the rest of the island. The extremely difficult terrain has prevented the exploitation of much of the forest.

Agricultural and coastal industrial land use has hurt much of Maui's coastal regions. Many of Maui's extraordinary coral reefs have been damaged by pollution, run-off, and tourism, although finding sea turtles, dolphins, and Hawaii's celebrated tropical fish, is still common. Leeward Maui used to boast a vibrant dry 'cloud forest' as well but this was destroyed by human activities over the last three hundred years.[17]

Wildlife

The birdlife of Maui lacks the high concentration of endemic birdlife found in some other Hawaiian islands. As recently as 200,000 years ago it was linked to the neighboring islands of Molokai, Lanai, and Kaho'olawe in a large island called Maui Nui, thus reducing the chance of species endemic to any single one of these. Although Molokai does have several endemic species of birds, some extinct and some not, in modern times Maui, Lanai, and Kaho'olawe have not had much endemic birdlife. In ancient times during and after the period in which Maui was part of Maui Nui, Maui boasted a species of moa-nalo (which was also found on Molokai, Lanai, and Kaho'olawe), a species of harrier (the Wood harrier, shared with Molokai), an undescribed sea eagle (Maui only), and three species of ground-dwelling flightless ibis (Apteribis sp.), plus a host of other species. Today, the most notable non-extinct endemics of Maui are probably the 'Akohekohe (Palmeria dolei) and the Maui parrotbill (Pseudonestor xanthophrys), also known as Kiwikiu, both of which are critically endangered and only found in an alpine forest on the windward slopes of Haleakala. Conservation efforts have looked at how to mitigate female parrotbill mortality since this has been identified as a key driving factor driving the decline in population. The parrotbill has a notable lack of resistance to mosquito-born diseases, so only forests above 1500 meters of elevation provide refuge for most parrotbills. The habitat is in the process of being restored on leeward east Maui as of 2018.[18] As Maui's population continues to grow, the previously undeveloped areas of the island that provided a refuge for the wildlife are decreasing in size as they are becoming more developed. This is proving to be a risk for the endangered species of the island. Both flora and fauna habitats need to be protected for the sake of the numerous endangered species that live there. More than 250 species of native flora are federally listed as endangered or threatened.[19] Birds found on other islands as well as Maui include the I'iwi (Drepanis coccinea], 'Apapane (Himatione sanguinea), Hawai'i 'Amakihi (Chlorodrepanis virens), as Maui 'Alauahio (Paroreomyza montana) well as the Nene (Branta sandvicensis, the state bird of Hawaii), Hawaiian coot (Fulica alai), Hawaiian stilt (Himantopus mexicanus knudseni) and a number of others. The Winter months provide a great opportunity for whale watching, as thousands of humpback whales migrate annually and pass by the island.

History

Polynesians from Tahiti were the original people to populate Maui. The Tahitians introduced the kapu system, a strict social order that affected all aspects of life and became the core of Hawaiʻian culture. Modern Hawaiʻian history began in the mid-18th century. Kamehameha I, king of the island of Hawaiʻi, invaded Maui in 1790 and fought the inconclusive Battle of Kepaniwai, but returned to Hawaiʻi to battle a rival, finally subduing Maui a few years later.

On November 26, 1778, explorer James Cook became the first European to see Maui. Cook never set foot on the island because he was unable to find a suitable landing. The first European to visit Maui was the French admiral Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse, who landed on the shores of what is now known as La Perouse Bay on May 29, 1786. More Europeans followed: traders, whalers, loggers (e.g., of sandalwood) and missionaries. The latter began to arrive from New England in 1823, settling in Lahaina, which at that time was the capital. They clothed the natives, banned them from dancing hula, and greatly altered the culture. The missionaries taught reading and writing, created the 12-letter Hawaiian alphabet, started a printing press in Lahaina, and began writing the islands' history, which until then was transmitted orally.[20] Ironically, the missionaries both altered and preserved the native culture. The religious work altered the culture while the literacy efforts preserved native history and language. Missionaries started the first school in Lahaina, which still exists today: Lahainaluna Mission School, which opened in 1831.

At the height of the whaling era (1843–1860), Lahaina was a major center. In one season over 400 ships visited with up to 100 anchored at one time in Lāhainā Roads. Ships tended to stay for weeks rather than days, fostering extended drinking and the rise of prostitution, against which the missionaries vainly battled. Whaling declined steeply at the end of the 19th century as petroleum replaced whale oil.

Kamehameha's descendants reigned until 1872. They were followed by rulers from another ancient family of chiefs, including Queen Liliʻuokalani, deposed in the 1893 overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii by American business interests. One year later, the Republic of Hawaii was founded. The island was annexed by the United States in 1898 and made a territory in 1900. Hawaiʻi became the 50th U.S. state in 1959.

In 1937, Vibora Luviminda trade union conducted the last strike action of an ethnic nature in the Hawaiʻian Islands against four Maui sugarcane plantations, demanding higher wages and the dismissal of five foremen. Manuel Fagel and nine other strike leaders were arrested, and charged with kidnapping a worker. Fagel spent four months in jail while the strike continued. Eventually, Vibora Luviminda made its point and the workers won a 15% increase in wages after 85 days on strike, but there was no written contract signed.

Maui was centrally involved in the Pacific Theater of World War II as a staging center, training base, and rest and relaxation site. At the peak in 1943–1944, more than 100,000 soldiers were there. The main base of the 4th Marine Division was in Haiku. Beaches were used to practice landings and train in marine demolition and sabotage.

Modern development

The island experienced rapid population growth through 2007, with Kīhei one of the most rapidly growing towns in the United States (see chart, below). The island attracted many retirees, adding service providers for them to the rapidly increasing number of tourists. Population growth produced strains, including traffic congestion, housing unaffordability, and issues of access to water.

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 40,103 | — | |

| 1960 | 35,717 | −10.9% | |

| 1970 | 38,691 | 8.3% | |

| 1980 | 62,823 | 62.4% | |

| 1990 | 91,361 | 45.4% | |

| 2000 | 117,644 | 28.8% | |

| 2010 | 144,444 | 22.8% | |

| 2020 | 168,307 | 16.5% | |

| State of Hawaii [5] | |||

Most recent years have brought droughts, resulting in the ʻĪao aquifer being drawn at possibly unsustainable rates above 18 million U.S. gallons (68,000 m3) per day. Recent estimates indicate that the total potential supply of potable water on Maui is around 476 million U.S. gallons (1,800,000 m3) per day, virtually all of which runs off into the ocean.

Water for sugar cultivation comes mostly from the streams of East Maui, routed through a network of tunnels and ditches hand dug by Chinese laborers in the 19th century. In 2006, the town of Paia successfully petitioned the county against mixing in treated water from wells known to be contaminated with both 1,2-dibromoethane and 1,2-dibromo-3-chloropropane from former pineapple cultivation in the area (Environment Hawaii, 1996). Agricultural companies have been released from all future liability for these chemicals (County of Maui, 1999). In 2009, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and others successfully argued in court that sugar companies should reduce the amount of water they take from four streams.[22]

In 1974, Emil Tedeschi of the Napa Valley winegrower family of Calistoga, California, established the first Hawaiian commercial winery, the Tedeschi Winery at Ulupalakua Ranch.

In the 2000s, controversies raged over whether to continue rapid real-estate development, vacation rentals in which homeowners rent their homes to visitors, and Hawaii Superferry. In 2003, Corey Ryder of the Earth Foundation gave a presentation regarding the unique situation on Maui, "Hazard mitigation, safety & security", before the Maui County Council.[23] In 2009, the county approved a 1,000-unit development in South Maui in the teeth of the financial crisis. Vacation rentals are now strictly limited, with greater enforcement than previously. Hawaii Superferry, which offered transport between Maui and Oahu, ceased operations in May 2009, ended by a court decision that required environmental studies from which Governor Linda Lingle had exempted the operator.[24]

In 2016, Maui residents convinced officials to switch to organic pesticides for highway applications after they found out that label requirements for glyphosate formulations were not being followed.[25]

Economy

The major industry in Maui is tourism. Other large sectors include retail, health care, business services, and government. Maui also has a significant presence in agriculture and information technology.

The unemployment rate reached a low of 1.7% in December 2006, rising to 9% in March 2009[26] before falling back to 4.6% by the end of 2013[27] and to 2.1% in January, 2018.[28]

Agriculture

Maui's primary agriculture products are corn and other seeds, fruits, cattle, and vegetables.[29] Specific products include coffee, macadamia nuts, papaya, flowers and fresh pineapple. Historically, Maui's primary products were sugar and pineapple. Maui Land & Pineapple Company[30] and Hawaiian Commercial and Sugar Company[31] (HC&S, a subsidiary of Alexander and Baldwin Company) dominated agricultural activity. In 2016, sugar production ended.[32] Haliimaile Pineapple Co. grows pineapple on former Maui Land & Pineapple Co. land.[33]

In November 2014, a Maui County referendum enacted a moratorium on genetically engineered crops.[34] Shortly thereafter Monsanto and other agribusinesses obtained a court injunction suspending the moratorium.[35]

Information technology

Most technology organizations that are located on the island populate the Maui Research & Technology Park[36] which is located on the coast of Maui. This region takes up 400 acres of Kihei which is home to many information technology organizations and companies such as the Maui High-Performance Computing Center, Maui Research and Technology Center, and Maui Brewing Company. The Park includes areas designated for research, such as offices, labs, and data centers. The Maui Research & Technology Park was opened in 1991 to create a mixed-use community, though only a portion of the area is dedicated to this mixed-use community. The mixed-use community was updated in the Master Plan in 2016.

The Maui High Performance Computing Center at the Air Force Maui Optical and Supercomputing observatory[37] in Kīhei is a United States Air Force research laboratory center that is managed by the University of Hawaii. It provides more than 10 million hours of computing time per year to the research, science, and military communities.

Another promoter of high technology on the island is the Maui Research and Technology Center,[38] also located in Kihei. It is a program of the High Technology Development Corporation,[39][40] an agency of the State of Hawaii, whose focus is to facilitate the growth of Hawaii's commercial high-technology sector.[41]

Astrophysics

Maui is an important center for advanced astronomical research. The Haleakala Observatory[42] was Hawaii's first astronomical research and development facility, operating at the Maui Space Surveillance Site (MSSS) electro-optical facility. "At the 10,023-foot summit of the long-dormant volcano Haleakala, operational satellite tracking facilities are co-located with a research and development facility providing data acquisition and communication support. The high elevation, dry climate, and freedom from light pollution offer virtually year-round observation of satellites, missiles, man-made orbital debris, and astronomical objects."[43]

Sports

Snorkeling

_(30799850077).jpg.webp)

Snorkeling is one of the most popular activities on Maui, with over 30 beaches and bays to snorkel at around the island. Maui's trade winds tend to come in from the northeast, making the most popular places to snorkel on the south and west shores of Maui. Having many mountains on Maui helps with the trade winds not being able to reach the beaches located on the south and west of the island, making the ocean water very clear.

Windsurfing

Maui is a well-known destination for windsurfing. Kanaha Beach Park is a very well-known windsurfing spot and may have stand-up paddle boarders or surfers if there are waves and no wind. Windsurfing has evolved on Maui since the early 1980s when it was recognized as an ideal location to test equipment and publicize the sport.

Surfing

One of the most popular sports in Hawaii. Ho'okipa Beach Park is one of Maui's most famous surfing and windsurfing spots. Other famous or frequently surfed areas include Slaughterhouse Beach, Honolua Bay, Pe'ahi (Jaws), and Fleming Beach. The north side of Maui absorbs the most swell during the winter season and the south and west in the summertime. Due to island blocking, summer south swells tend to be weak and rare.

Kitesurfing

One of the newest sports on Maui is kitesurfing, particularly at Kanaha Beach Park.

Tourism

.jpg.webp)

The big tourist spots in Maui include the Hāna Highway, Haleakalā National Park, Iao Valley, and Lahaina.

The Hāna Highway runs along the east coast of Maui, curving around mountains and passing by black sand beaches and waterfalls. Haleakalā National Park is home to Haleakalā, a dormant volcano. Snorkeling can be done at almost any beach along the Maui coast. Surfing and windsurfing are also popular in Maui.

The main tourist areas are West Maui (Kāʻanapali, Lahaina, Nāpili-Honokōwai, Kahana, Napili, Kapalua) and South Maui (Kīhei, Wailea-Mākena). The main port of call for cruise ships is located in Kahului. There are also smaller ports located at Lahaina Harbor (located in Lahaina) and Maʻalaea Harbor (located between Lahaina and Kihei). Lahaina is one of the main attractions on the island with an entire street of shops and restaurants that leads to a pier where many set out for a sunset cruise or whale-watching journey. Known locally as Lahainatown, it has a long and diverse history from its Hawaiian population beginnings to the arrival of travelers and settlers and its use as a significant whaling port.[44]

Maui County welcomed 2,207,826 tourists in 2004 rising to 2,639,929 in 2007 with total tourist expenditures north of US$3.5 billion for the Island of Maui alone. While the island of Oʻahu is most popular with Japanese tourists, the Island of Maui appeals to visitors mainly from the U.S. mainland and Canada: in 2005, there were 2,003,492 domestic arrivals on the island, compared to 260,184 international arrivals.

While winning many travel industry awards as Best Island In The World[45] in recent years concerns have been raised by locals and environmentalists about the overdevelopment of Maui. Visitors are being urged to be conscious of reducing their environmental footprint[46] while exploring the island. Several activist groups, including Save Makena,[47] have gone as far as taking the government to court to protect the rights of local citizens.[48]

Throughout 2008 Maui suffered a major loss in tourism compounded by the spring bankruptcies of Aloha Airlines and ATA Airlines. The pullout in May of the second of three Norwegian Cruise Line ships also hurt. Pacific Business News reported a $166 million loss in revenue for Maui tourism businesses.[49]

Transportation

The Maui Bus is a county-funded program that provides transportation around the island for nominal fares.[50]

Airports

Three airports provide air service to Maui:

- Hana Airport provides regional service to eastern Maui

- Kahului Airport in central Maui is an international airport and the island's busiest

- Kapalua Airport provides regional service to western Maui

Healthcare

There are two hospitals on the island of Maui. The first, Maui Memorial Medical Center, is the only acute care hospital in Maui County. It is centrally located in the town of Wailuku approximately 4 miles from Kahului Airport. The second, Kula Hospital, is a critical access hospital located on the southern half of the island in the rural town of Kula. Kula Hospital, along with Lanai Community Hospital (which is located in Maui County but on the neighboring island of Lanai), are affiliates of Maui Memorial Medical Center. All three hospitals are open 24/7 for emergency access. Although not technically a hospital or emergency room, Hana Health Clinic (or Hana Medical Center), located in the remote town of Hana on the southeastern side of the island, works in cooperation with American Medical Response and Maui Memorial Medical Center to stabilize and transport patients with emergent medical conditions. It too is open 24/7 for urgent care and emergency access.[51][52][53]

International relations

Maui is twinned with:

Funchal, Madeira, Portugal

Funchal, Madeira, Portugal Arequipa, Perú

Arequipa, Perú Quezon City, Philippines, since 6 March 1970[54]

Quezon City, Philippines, since 6 March 1970[54]

Notable people

- Sil Lai Abrams, writer

- Luther Aholo (1833– 1888), politician

- Lydia Kaʻonohiponiponiokalani Aholo (1878– 1979), daughter of Queen Liliʻuokalani

- Wallace M. Alexander (1869– 1939), businessman

- Irmgard Farden Aluli (1911– 2001), songwriter

- Renee Alway, fashion model

- Samuel C. Armstrong (1839– 1893), Union Army general

- Chris Berman, ESPN sportscaster[55][56]

- Cedric Ceballos, former NBA basketball player

- Charlie Chong (1926– 2007), politician

- Alice Cooper, musician[57]

- William H. Cornwell (1843– 1903), businessman

- Destin Daniel Cretton, film director and screenwriter

- Dylan Donkin, rock musician

- Lani Doherty, surfer

- Clint Eastwood, actor/director[55]

- Joe Eszterhas, Hungarian-American screenwriter and author[58]

- Thomas Wright Everett (1823– 1895), former governor of Maui (1882– 1883)

- Harry Field (1911– 1964), former American football player

- Mick Fleetwood, musician[59]

- Abraham Fornander (1812– 1887), judge

- Beverly Gannon, chef

- Amy Hānaialiʻi Gilliom, songwriter

- Kendall Grove, mixed martial artist

- Barney F. Hajiro (1916– 2011), Medal of Honor recipient

- S. N. Haleʻole (1819– 1866), writer and historian

- Woody Harrelson, actor[55]

- George Harrison (1943– 2001), musician/guitarist of The Beatles[60]

- Hon Chew Hee (1906– 1993), artist

- David Kahalekula Kaʻauwai (1833– 1856), politician

- William Hoapili Kaʻauwai (1835– 1874), politician

- Zorobabela Kaʻauwai (1799– 1856), politician

- Willie K (1960– 2020), musician

- Anthony T. Kahoʻohanohano (1930– 1951), Medal of Honor recipient

- Kapahei Kauai (1825– 1893), judge

- Helio Koaʻeloa (1815– 1846), missionary

- Kamaka Kūkona, musician

- Kris Kristofferson, musician[55]

- Charles Lindbergh (1902– 1974), aviator

- Garrett Lisi, physicist

- James Makee (1813– 1879), businessman

- David Malo (1793– 1853), historian

- Cecilia Suyat Marshall, historian

- Patsy Mink (1927– 2002), lawyer and politician

- Andy Miyamoto, former baseball player

- Dave Murray, musician/guitarist of Iron Maiden

- Jim Nabors (1930– 2017), actor/singer[61]

- George Naea (died 1854), high chief of the Kingdom of Hawaii

- Linda Nagata, author

- Betsy Nagelsen, former tennis player

- Don Nelson, former NBA basketball player and coach[55]

- Willie Nelson, musician

- Danny Ongais, former CART, IndyCar, Formula One driver

- Kalani Pe'a, songwriter

- Jeff Peterson, musician

- Poncie Ponce (1933– 2013), actor and comedian

- Richard Pryor (1940– 2005) comedian[62]

- Puaaiki (1785– 1844), preacher

- Michael Reeves, YouTube personality

- Kealiʻi Reichel, musician

- Bob Rock, musician/record producer[63]

- Will Rodgers, NASCAR driver

- Tadashi Sato (1923– 2005), artist

- Daniel Scott, American soccer player

- Zach Scott, American soccer player

- Mike Stone, martial artist

- Kurt Suzuki, baseball player

- Hannibal Tavares (1919– 1998), politician

- Kanekoa Texeira, a former baseball pitcher who is currently the manager for the Mississippi Braves

- Kiana Tom, television host for ESPN

- Rose Tribe (1890– 1934), singer

- Shan Tsutsui, former Lieutenant Governor of Hawaii (2012– 2018)

- Steven Tyler, lead singer of Aerosmith[55]

- Camile Velasco, singer

- Shane Victorino, former baseball outfielder[55]

- Armine von Tempski (1892– 1943), writer

- Robert William Wilcox (1855– 1903), politician

- Owen Wilson, actor[55]

- Oprah Winfrey, talk show host[64]

- Becky Worley, journalist

- Weird Al Yankovic, musician[65]

- Wally Yonamine (1925– 2011), athlete

References

- "Table 5.13 – Elevation of Major Summits" (PDF), The State of Hawaii Data Book 2015, State of Hawaii, 2015, archived (PDF) from the original on February 7, 2017, retrieved July 23, 2007

- "Hawaii January 29, 2014". January 29, 2014. Archived from the original on January 10, 2015. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- Kinney, Ruby Kawena (1956). "A Non-purist View of Morphomorphemic Variations in Hawaiian Speech". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 65 (3): 282–286.

- "Table 5.08 – Land Area of Islands: 2000" (PDF), 2004 State of Hawaii Data Book, State of Hawaii, 2004, archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2012, retrieved July 23, 2007

- "Table 1.05 – Resident Population of Islands 1950 to 2010" (PDF), 2010 State of Hawaii Data Book, State of Hawaii, 2010, archived (PDF) from the original on August 13, 2012, retrieved September 25, 2011

- Nyakundi, Colvin Tonya; Davidson, John (March 22, 2016). Traveling to Maui Island: The Ultimate and Most Comprehensive Guidebook. Mendon, Utah: Mendon Cottage Books. p. 193. ISBN 9781310226106. Retrieved May 14, 2020 – via Google Books.

- Sterling, Elspeth P. (June 1, 1998). Sites of Maui. Bishop Museum Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-930897-97-0.

- "Hawaiian Volcano Observatory". volcanoes.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- "Volcano Watch — Youngest lava flows on East Maui probably older than A.D. 1790". United States Geological Survey. September 9, 1999. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- "Haleakalā". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- "Once a big island, Maui County now four small islands". Volcano Watch. Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. April 10, 2003. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- "Maui — weather by month, water temperature". Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- Imada, Lee. "'Big Bog' ranks among wettest spots in Hawaii, possibly world". The Maui News. Archived from the original on June 11, 2013. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- "NASA Earth Observations Data Set Index". NASA. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- "Population Estimates". iwc.int. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- "Record Number of Whales Sighted During Great Whale Count". pacificwhale.org. Archived from the original on February 25, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

- "History of Sandalwood on Maui". tourmaui.com. June 30, 2016. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- Mounce, Hanna L.; Warren, Christopher C.; McGowan, Conor P.; Paxton, Eben H.; Groombridge, Jim J. (May 9, 2018). "Extinction Risk and Conservation Options for Maui Parrotbill, an Endangered Hawaiian Honeycreeper". Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management. 9 (2): 367–382. doi:10.3996/072017-JFWM-059.

- "Maui Island Plan". Archived from the original on April 2, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- Goldman, Rita (May 2008). "Hale Pa'i". Maui Magazine. Archived from the original on May 31, 2010. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- "VIDEO: Lahaina fire fatalities rise to 93; Green said toll will 'continue to climb'". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- "Pending ruling restores water to 4 streams on Maui". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- "Earth foundation-corey-ryder". Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "Supreme Court ruling forces Hawaii Superferry shutdown, layoffs". Archived from the original on July 18, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- "How Activists Are Restricting Use of a Major Pesticide". Time. Archived from the original on January 29, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- "Unemployment rate". Yahoo. December 4, 2010. Archived from the original on April 2, 2022. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- "VIDEO: Maui Unemployment Rate Lowest Since 2008 – Maui Now". mauinow.com. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- "Maui Now: Maui Unemployment Rate Remains Low in January". Maui Now | Maui Unemployment Rate Remains Low in January. Archived from the original on March 15, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- US Department of Agriculture (2013). "20121 Census of Agriculture – Maui County" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 3, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- "Maui Land & Pineapple Company homepage". Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- "Commercial and Sugar Company". Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- "Bittersweet End to Cane Plantation Days". hpr2.org. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- "Maui Pine assets sold for quarter of worth – Pacific Business News". Pacific Business News. Archived from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- "Election results show money doesn't guarantee votes". November 5, 2014. Archived from the original on December 16, 2014. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- Audrey McAvoy; and KHON2 (November 14, 2014). "Federal judge blocks Maui GMO moratorium". Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- "Maui Research and Technology Park". mauitechpark. Archived from the original on March 26, 2022. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- "Maui High Performance Computing Center homepage". Archived from the original on September 21, 2010. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- "Maui Research & Technology Center". Archived from the original on March 4, 2009. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- "What is the Maui Research & Technology Center?". Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- "TTDC homepage". Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- "Hawaii's Emerging Technology Industry" (PDF). January 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 21, 2006. Retrieved August 9, 2006.

- "Institute for Astronomy, Maui homepage". Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- "Maui Space Surveillance Site". Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- "Lahaina Town History Timeline | Maui, Hawaii Events". lahainatown.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- "Best Island In The World" (PDF) (Press release). Maui Visitors Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2009.

- "Reduce Your Environmental Footprint While Traveling to Hawaii". Kahana Village. November 2019. Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- "Save Makena". Save Makena. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- Tayfun King Fast Track (March 9, 2009). "Concerns Of Overdevelopment In Maui". BBC World News. Archived from the original on March 14, 2021. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- Blair, Chad (October 19, 2008). "Maui feels pain of $166M tourism decline". Pacific Business News. American City Business Journals. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- "Bus Service Information". County of Maui. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- "Maui Memorial Medical Center". Archived from the original on November 1, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- "Kula Hospital". Archived from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- "Hana Health Clinic". Archived from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- "Sister Cities". The Local Government of Quezon City. Archived from the original on October 1, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- "Celebrities in Maui Hawaii". Buy or Sell Maui Real Estate. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- WILNER, BARRY (May 1, 2017). "Chris Berman changing role at ESPN". Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 23, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- JOHN DALY (January 4, 2019). "Alice Cooper Spends New Year's Eve with Lynda Carter, Steven Tyler in Hawaii". californiarocker.com. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

All are friends and neighbors on the island of Maui, commonly referred to as "Mauifornia" for its overwhelming population of Californians on the island.

- "Joe Eszterhas February 6, 2009". PBS. February 6, 2009. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- Paul Wood (July 6, 2019). "Rock Meets Mountain: This Kula abode is where Mick Fleetwood unscrews up". mauimagazine.net. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

…he makes it clear that the Napili house is the actual domicile…

- Huntley, Elliot (2006) [2004]. Mystical One: George Harrison: After the Break-up of the Beatles. Guernica Editions. ISBN 978-1-55071-197-4. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- "Aloha! Jim Nabors' Massive 170-Acre Maui Retreat Is Available for $4.5M". sfgate.com. October 3, 2019. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- Michael Oricchio (May 31, 1995). "Pryor wrote the book on comedy and now, a memoir of his tumultuous life". Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- Darren Paltrowitz (July 6, 2019). "Legendary Music Producer Bob Rock On Why He Has Lived In Hawaii For 20+ Years". Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

My home is basically the island…

- Tinker, Ben; Boyette, Chris (August 11, 2023). "Oprah Winfrey visits residents in shelters affected by Maui wildfires". CNN. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

Publications

- Kyselka, Will; Lanterman, Ray E. (1980). Maui, How It Came to Be. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0530-2.