Max Abraham

Max Abraham (German: [ˈaːbʀaham]; 26 March 1875 – 16 November 1922) was a German physicist known for his work on electromagnetism and his opposition to the theory of relativity.

Max Abraham | |

|---|---|

Max Abraham | |

| Born | 26 March 1875 |

| Died | 16 November 1922 (aged 47) |

| Nationality | German |

| Known for | Abraham–Lorentz force Abraham–Minkowski controversy |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physicist |

| Doctoral advisor | Max Planck |

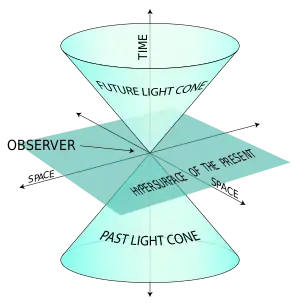

| Special relativity |

|---|

|

|

Biography

Abraham was born in Danzig, Imperial Germany (now Gdańsk in Poland) to a family of Jewish merchants. His father was Moritz Abraham and his mother was Selma Moritzsohn. Attending the University of Berlin, he studied under Max Planck. He graduated in 1897. For the next three years, Abraham worked as Planck's assistant.[1]

From 1900 to 1909, Abraham worked at Göttingen as a privatdozent, an unpaid lecturing position. Abraham developed his theory of the electron in 1902, in which he hypothesized that the electron was a perfect sphere with a charge divided evenly around its surface. Abraham's model was competing with that developed by Hendrik Lorentz (1899, 1904) and Albert Einstein (1905) which seem to have become more widely accepted; nevertheless, Abraham never gave up his model, since he considered it was based on "common sense". Abraham was a staunch opponent of the theory of relativity.[2]

In 1909 Abraham travelled to the United States to accept a position at the University of Illinois, but ended up returning to Göttingen after a few months. He was later invited to Italy by Tullio Levi-Civita, and found work as the professor of rational mechanics at the Politecnico di Milano university until 1914.

When World War I started, Abraham was forced to return to Germany. During this time he worked on the theory of radio transmission. After the war, he still was not allowed back into Milan, so until 1921 he worked at Stuttgart as the professor of physics at Technische Hochschule.

After his work at Stuttgart, Abraham accepted the position of chair in Aachen; however, before he started his work there he was diagnosed with a brain tumor. He died on 16 November 1922 in Munich, Germany.

After his death, Max Born and Max von Laue wrote about him in an obituary: He loved his absolute aether, his field equations, his rigid electron just as a youth loves his first flame, whose memory no later experience can extinguish.[3]

Publications

- Abraham, M. (1902). . Göttinger Nachrichten (in German): 20–41.

- Abraham, M. (1902). "Prinzipien der Dynamik des Elektrons" (PDF). Physikalische Zeitschrift (in German). 4 (1b): 57–62. Bibcode:1902AnP...315..105A. doi:10.1002/andp.19023150105.

- Abraham, M. (1903). "Prinzipien der Dynamik des Elektrons" (PDF). Annalen der Physik (in German). 10 (1): 105–179. Bibcode:1902AnP...315..105A. doi:10.1002/andp.19023150105.

- Abraham, M. (1904). . Physikalische Zeitschrift (in German). 5: 576–579.

- Abraham, M. (1904). "Zur Theorie der Strahlung und des Strahlungsdruckes". Annalen der Physik (in German). 14 (7): 236–287. Bibcode:1904AnP...319..236A. doi:10.1002/andp.19043190703. Archived from the original on 2007-06-11.

- Abraham, M.; Föppl. A. (1904). Theorie der Elektrizität: Einführung in die Maxwellsche Theorie der Elektrizität (in German). Leipzig: Teubner.[4]

- Abraham, M. (1905). Theorie der Elektrizität: Elektromagnetische Theorie der Strahlung (in German). Leipzig: Teubner.[5] Zweite Auflage. B.G. Teubner. 1908.[6]

- Abraham, M. (1912). "Relativitaet und Gravitation. Erwiderung auf eine Bemerkung des Herrn A. Einstein". Annalen der Physik (in German). 38 (10): 1056–1058. Bibcode:1912AnP...343.1056A. doi:10.1002/andp.19123431013.

- Abraham, M. (1912). "Nochmals Relativitaet und Gravitation. Bemerkungen zu A. Einsteins Erwiderung". Annalen der Physik (in German). 39 (12): 444–448. Bibcode:1912AnP...344..444A. doi:10.1002/andp.19123441208.

- Abraham, M. (1914). "Die neue Mechanik". Scientia (in German). 15: 8–27. Archived from the original on 2007-07-14. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

References

- Max Abraham. MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- Howard, Don; Stachel, John. (1989). Einstein and the History of General Relativity. Birkhäuser Boston. p. 183. ISBN 9780817633929

- Pais, Abraham (2005). Subtle is the Lord. Oxford University Press. p. 232. ISBN 0-19-280672-6.

- Wilson, E. B. (1905). "Review: Theorie der Elektrizität, vol. 1 by M. Abraham & A. Föppl" (PDF). Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 11 (7): 383–387. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1905-01236-2.

- Wilson, E. B. (1908). "Review: Theorie der Elektrizität, vol. 2 by M. Abraham" (PDF). Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 14 (3): 203–207. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1908-01601-X.

- Wilson, E. B. (1910). "Review of Theorie der Elektrizität. Zweiter Band, Zweite Auflage" (PDF). Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 16: 545–546. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1910-01975-3.

Further reading

- Goldberg, Stanley (1970). "Abraham, Max". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 23–25. ISBN 0-684-10114-9.

External links

Works by or about Max Abraham at Wikisource

Works by or about Max Abraham at Wikisource German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Max Abraham

German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Max Abraham